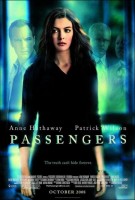

Tagline: The truth can’t hide forever.

After a horrific plane crash, a young therapist, Claire Summers (Anne Hathaway), is assigned by her mentor (Andre Braugher) to counsel the flight’s five remaining passengers. Claire’s difficulties in taking on such an assignment are made all the more complex when she’s confronted by Eric (Patrick Wilson), a passenger who refuses her help and instead uses the crash as an excuse to break the rules and openly court her. As Claire struggles to maintain a professional distance from Eric, her other patients struggle with recollections of the accident which are at odds with the airline’s official explanation.

After their memories of a possible mid-air explosion surface, the passengers begin mysteriously disappearing, and Claire suspects the airline is behind it. Determined to uncover the truth, Claire is drawn deeper into a conspiracy—and deeper into a relationship with Eric—that will soon collide in an explosive twist of fate.

About the Story

A late night phone call and fire on the distant horizon tell therapist Claire Summers (Anne Hathaway) she’d better get to the hospital. A passenger plane has just gone down and she’s needed to counsel those who miraculously walked away from the crash. Waiting for her at the hospital is Perry Jackson (Andre Braugher), a childhood teacher who has since taken on the role of Claire’s mentor, and his expectation that she turn her skills treating children with post-traumatic stress disorder to the handful of adults now experiencing the same. Claire balks at Perry’s suggestion—claims she’s not up to the task—but Perry insists it’s time for Claire to “stretch out of that comfort zone” of hers and progress professionally.

Before sending her into battle, Perry warns Claire one patient in particular “will require a bit more work.” This is Eric Clark (Patrick Wilson), and, while the others are in obvious states of shock, he’s euphoric. He greets Claire’s offer of assistance with sarcasm but then inquires—somewhat mischievously—if she makes house calls. The question at first throws Claire off her game but she quickly recovers: she agrees to meet Eric at his home, privately convinced he’ll agree to counseling once she’s made contact again.

After organizing a group session for the passengers, Claire returns to her apartment. At first glance it appears hers is a well-organized life, but a closer look reveals the disorder masked within: unread newspapers are piled up on the kitchen counter, mail has accumulated on the dining table and, as her neighbor Toni (Dianne Wiest) arrives to announce, Claire has left her clothes in the communal dryer. Toni’s attempts at conversation are averted by Claire, a theme repeated when Claire leaves a jumbled, hesitant telephone message for her sister, Emma, the distance between the sisters seemingly unbridgeable.

“Claire has a lot of things keeping her back,” explains director Rodrigo Garcia. “She has unresolved issues with her sister, she’s not doing the work as a doctor that she should be doing, and she has never engaged on a personal level in a risky way.” Writer Ronnie Christensen agrees, comparing Claire to a “beautiful flower that hasn’t blossomed yet. She is someone who has thought herself into a box. She doesn’t think outside of that, she doesn’t go after the things she wants or loves in life. Claire is in a box and she needs somebody to help her out of it.”

Though Claire doesn’t know it yet, that someone will be Eric. Contrary to his earlier assertions, Eric is deeply troubled by the crash. Awakened abruptly by a nightmare, Eric’s instinct is to run, literally, as fast as he can, the pain in his body proof that he’s alive. As Eric runs like a madman through the streets, a dog barks erratically at him, an elderly man watches intently, and the city hums on, oblivious.

Later, as promised, Claire pays a professional visit at Eric’s townhouse. Eric announces he has quit his job as VP of a brokerage firm and is reevaluating his priorities. Recognizing this common response to tragedy, Claire tries to dig deeper but her valiant efforts are thwarted at every turn: a casual touch of her hair here, a compliment there, an invitation to be intimate poorly disguised as a joke. Eric is a paradox: he’s determined not to accept counseling, determined to remain separate from the other passengers, yet desperate to connect to something tangible, meaningful, to connect to Claire.

That Eric needs to reconnect is reflected in his reassessment of his former life. As Eric tells Claire, says Patrick Wilson, “Everything before was about not communicating. Eric has all these gadgets—phones, instant-messengers, computers—allegedly designed to keep him connected but which he has suddenly realized keep him away from people. His is a very closed-off world.”

“Eric has been very successful professionally,” adds director Garcia, “but has been caught in that rut of doing well, making money, buying toys. There’s something of the successful boy who hasn’t grown into a man. After the crash, he wants to clean things up.” But Eric is still that boy: he denies he’s in pain and his attempt at reconnecting is inappropriate, a violation of Claire’s professional ethics.

And, true to his promise, Eric was absent earlier that morning when Claire lead the first group session. In attendance was thirty-something Dean (Ryan Robbins), wracked with shame over his perceived cowardice; twenty-ish Shannon (Clea DuVall), pretty and full of youthful bravado; Norman (Don Thompson), a blustery, nervous man in his fifties; and Janice (Chelah Horsdal), a decade younger than Norman and twice as reluctant to speak. As the group tried to recollect the events that lead up to the crash, outside the window Claire noticed another, uninvited guest: a tall, blonde man in an old, dirty overcoat, watching intently from among the bushes, who moved on silently when Claire questioned his presence.

Mysterious figures appear to be watching the passengers, and when Claire meets up with Jed Arkin (David Morse), a representative of the airline, it’s clear he has something to hide. He dismisses any talk of an explosion—the official position is “pilot error”—and quickly ends their conversation. Then later, while at the library, Claire is followed by a woman who first appeared at the hospital after the crash. Is there a link? Is the airline keeping tabs on those who might talk?

David Morse insists there isn’t any conspiracy, but then he would, wouldn’t he? “Arkin represents the airline,” says Morse of his character, “and their rigid point of view about what happened. Claire believes there’s something more but he completely denies it: her patients have been through trauma; nutty things are coming into their heads. Arkin is pretty certain he knows what happened on that plane.”

The mystery deepens when Dean is inexplicably absent from the next group session, then deepens yet again when afterwards Norman informs Claire the tall, blonde man earlier seen lurking outside is following him. Norman is convinced the man is from the airline, monitoring the passengers because of an earlier accident that involved a mechanical malfunction. Another incident could sink them, Norman argues, and a corporation as large as this is “capable of anything to save their asses.” Claire assures Norman it’s just paranoia, a heightened state of post- traumatic vulnerability, but inwardly she’s on edge.

Claire’s stress is intensified when she next visits Eric. He’s still in denial but his actions speak to the contrary: he’s taken up painting, the mural on the wall emerging subliminally, he’s hounded by a barking dog only he can hear, and, most frightening of all, his inner turmoil is punctuated by impetuous, danger acts: darting out into traffic without warning and scaring the hell out of Claire. And through it all Eric remains annoyingly aloof and charmingly forward, continually testing Claire’s boundaries, drawing out the shared attraction he knows she feels.

“Much to her utter dismay,” confesses Anne Hathaway, “Claire is developing romantic feelings for Eric. So now she’s confronted with ethical issues she never anticipated. Suddenly she has to deal with her ambition and her brains challenging her heart. Which is going to rule her?”

Director Rodrigo Garcia sees in Eric “a single package” that confronts both Claire’s professional and personal limitations. “Claire is faced with the dilemma of how to help someone who doesn’t want to be a patient and who, at the same time, is openly courting her. Eric challenges Claire professionally, because he clearly needs help, and personally because she’s always been too cautious, too scared to get messy in a relationship. Eric comes as a single package: difficult patient and difficult love interest.”

Anne Hathaway admits the chemistry between Claire and Eric was easy to create. “Patrick and I had an easy rapport from the first rehearsal,” recalls Hathaway fondly. “He’s really down-to-earth, a wonderful person. I felt so comfortable with him off-camera and I think that comfort translated into the scenes. I felt I could trust him at every turn. And he’s the most gorgeous man, with everything on the outside mirrored within. He’s sublime.”

Wilson returns the compliment, calling Hathaway a woman with “this rare gift of being strong and smart and beautiful. And she’s funny. Anne’s becoming bigger by the day; there’s a lot of pressure yet she takes everything in stride.”

Unlike her character. Claire flees from Eric and heads for home, for sanctuary from her struggles. Though troubled by Emma’s continuing silence, Claire finds a moment of respite with Toni. Played by the inimitable Dianne Wiest, who brings a “vibrancy” to an otherwise small role, Toni’s relaxed, happy demeanor craftily draws Claire into the elder woman’s confidence.

“Sometimes,” explains producer Keri Selig, “you’ll tell a stranger things you wouldn’t tell your best friend because you think you’ll never see them again. Claire feels free with Toni, so Toni starts asking questions, drawing Claire in, subtly guiding her.” Claire opens up about the conflict with Eric, and is surprised when Toni warns of opportunities lost to cowardice. “Spread your wings, Claire,” she advises, “life is a moment.”

Toni’s words become flesh when Claire next sees Eric, his earlier euphoria replaced by a determination to take new risks, to experience life in all its richness. He invites Claire for an exhilarating ride on his new motorbike—sans helmets—then commandeers a stranger’s boat for a moonlight sail and nude swim. Eric is, says Patrick Wilson, “just reaching for life. He’s trying to put it all together. Whenever someone is faced with death, if you get another chance to live you want to live to the fullest. Eric doesn’t want to take anything for granted anymore. He wants to value what’s important to him, to live his life as passionately as he can. Because your time here is short.”

Eric’s enthusiasm proves infectious. Claire’s rebuffs ring more and more hollow until she finally submits to her desires. “I think of Eric as Claire’s liberator,” muses Anne Hathaway. “Claire is in a cage where the door was always open but she never realized it; she was always just flying around inside. Eric shows her there’s a whole world outside of that very limited space she’s contained herself in. He really pushes her buttons, pushes the envelope until she finally flies outside her comfort zone.”

Claire awakens the next morning a little regretful, her regret quickly turning to embarrassment when Arkin surprises her outside Eric’s door. Is Arkin following her? Claire turns to Perry for help but talk of a conspiracy doesn’t interest him. He’s more interested in how Claire is doing, how her patients are faring, how Eric is coping. Claire confesses Eric has become her lover yet, to her surprise, Perry doesn’t chastise her; instead, he suggests Eric has come to fill a void.

Andre Braugher, who plays Perry, explains that his character is firstly Claire’s mentor and “a mentor leads you from that place where you think you know everything to the point where you’re willing to really dig down and become what’s necessary to be great. Perry has always seen a tremendous promise in Claire that just needed a catalyst; that’s why he made her the head therapist for the crash. And now he’s trying to tell her she’s been squandering her life; that the paralysis that characterized her relationships in the past can’t be allowed to continue. Patrick’s character is a part of that, too, leading Claire to this realization.”

But while Perry has confidence in Claire’s abilities, not everyone is so supportive, Shannon in particular. “Shannon thinks Claire is an idiot,” explains Clea DuVall. “How can this little girl possibly help me?, she thinks. Besides, Shannon doesn’t think she needs help, that everything is fine.” Shannon questions Claire’s credentials, criticizes her techniques, aims sarcastic comments in Claire’s direction, yet continues attending the sessions, subconsciously in need of closure. “And then slowly,” adds DuVall, “the effect of the crash on her emerges and Shannon just slowly degrades emotionally through the film.”

The foil that Shannon provides is a small but important role that, in lesser hands, might appear cliché. “We really had to have Clea,” says producer Julie Lynn, “because Shannon is such a difficult role. Shannon doesn’t know if she’s coming or going, there’s so much ambiguity in her, so much confusion, so many changes, that you need a stellar actress to handle it. And what a face. The planes of Clea’s face are so beautiful and so interesting. And she was someone Rodrigo and I had worked with before. She makes Rodrigo light up like a Christmas tree when she comes on set, and me too.”

Tensions escalate when the blonde man that appeared to be spying on the group turns out to be another passenger, dazed and confused after the crash. He remembers an explosion, he tells Claire, and “the next thing I’m here, walking around like a zombie.” Convinced now her patients were right about a cover-up, Claire takes the man to the airport, determined to confront Arkin and his lies.

Claire finds Arkin at one of the terminals, and their argument quickly escalates into a shouting match then an outright fight when the blonde man attacks Arkin. Then, to Claire’s surprise, Janice appears to defend Arkin, clawing at the blonde man. When the dust finally settles, Claire is left alone with her confusion. What does Janice have to do with Arkin? And why is she now defending him?

Later that night, only Shannon returns to group counseling. Everyone, including Janice now, has disappeared. Claire panics and orders a frightened Shannon into the car then meets up with Eric. All retreat to the safety of Claire’s apartment. The safety proves illusive, however, for the next morning Eric has a meltdown, Shannon disappears, and Claire imagines a sinister side to Toni.

Turning now to the only person she thinks can help her, Claire arrives at Perry’s door. Instead of offering support, however, Perry denounces Claire’s theory of a cover-up as an “elaborate” story concocted to obscure the truth Claire needs to face. Claire “then comes to a point where she believes Perry and Toni are complicit, that they’ve been bought by the airline,” reckons Hathaway. “Claire feels her whole world has been turned upside down. She can’t trust anyone. But she still feels compelled to save everyone, to fight.” Claire accuses Perry of using her, of being a puppet master who manipulated her into doing the airline’s dirty work. She flees from his presence, frightened and bewildered.

Unsure of her next move, Claire turns impulsively to her sister but Emma isn’t home. Then, to Claire’s astonishment, Arkin arrives—and he’s a changed man, finally acknowledging responsibility. “Arkin just felt so horribly guilty,” says David Morse, “so responsible for what happened that he couldn’t face it; he had to put it in terms of somebody else has done something. The moment where he realizes the somebody else is him, it’s brutal. There’s such a graceful revelation about him at the end.”

Arkin then deliberately forgets his briefcase, leaving Claire free to riffle through the airline’s documents. Among the papers Claire finds the lengthy passenger list—and the true magnitude of the event comes crashing down. Claire collapses, grief stricken. Moments pass as Claire digests the truth: no conspiracy, no men in black, just death and human suffering. Then, finally, clarity arrives. Claire composes herself and goes in search of Eric, at the pier preparing a boat. Having abandoned his former life, he’s sailing off into an unknown future. Claire, finally ready now to embark on her own new journey, joins Eric at the helm.

Back in Eric’s apartment, the finished mural glistens in the daylight: the view from a sailboat: the bow, the sails, and beyond it, the horizon. “Passengers is a thriller,” concludes producer Keri Selig, “but at the core it’s really a love story. Yes, Claire needs to solve the mystery, but she also needs to realize she has fallen in love and accept that, to get to the next place in her life.”

“A lot of thrillers are set up to be about the thrills,” adds producer Julie Lynn, “which aren’t necessarily in service to the characters and the journey they’re on. Here, the thrills and the romance and the plot are organically intertwined, not there just for the sake of the punch. This movie is more about reminding us that we get to choose how we feel about our lives. While we can’t control what happens around us, we can control our relationship to those circumstances and to other people. That’s how Passengers is different.”

About the Production

“It’s all about denial and truth bleeding through that denial,” says writer Ronnie Christensen. “No matter what scenario you’re in in life, no matter how bad it gets, truth always bleeds through.” For Christensen, the truth that inspired Passengers was his fear of parenthood as he approached the birth of his first child. That fear of the moment that changes your life forever was translated into a plane crash, that “scariest of situations,” through which emerges a love that bears witness to the truth. “I was really scared about having my first kid,” says Christensen. “In the process of writing Passengers I came up with this love story, this love that transcends all boundaries. Love is the only continuous thing through the story.”

In her analysis of Passengers, producer Keri Selig, a long-time friend of Christensen, goes further with the metaphor. “Ronnie was terrified of becoming a father because life as he knew it might be over. Passengers represents death and a new life beginning, life after death. When I read it I thought, wow, this is unbelievable.”

Christensen had been working with Selig and her partners, Matthew Rhodes and Judd Payne, on developing other projects, and gave them Passengers on a whim. The three producers read it independently one Sunday afternoon and on Monday they agreed it was a project worth pursuing. What struck them all was the surprise ending which, they agree, benefited from reading the script cold. “Because we hadn’t been prepped,” recalls Rhodes, “we had no idea what a huge surprise was in store for us. That’s what really hooked us on the movie.”

The project was sold to Mandate Pictures and then the producers set about finding a director. Selig had just seen Rodrigo Garcia’s Things You Can Tell Just By Looking At Her and was convinced he was the one for Passengers. “I went to everyone at Mandate and said, ‘This is our director.’ He wasn’t the most obvious choice, but to me he gets under character and he brings something fresh; his work is exquisite. I called his agent and begged her and Rodrigo to read the script. A month went by and no answer, so I started calling every day. Finally, as she tells it, she gave him the script just to get me off her phone sheet. And the day after he read it he said yes, so I guess persistence pays.”

“Rodrigo had just finished Nine Lives,” adds Judd Payne. “It hadn’t come out yet but we were able to see the picture and the performances were just unbelievable. We knew he was someone that would attract a phenomenal cast. So we hopped on the phone and started discussing Rodrigo with the talent agents. They were really excited; Rodrigo’s considered an actor’s director. Their response got us really jazzed and so we sent him the script.”

Garcia says he found the story engaging, “but definitely the events of the last twenty pages really captured me,” says the director. “The story is very strong, very emotional, and I have a preference for stories that involve leading ladies, stories for women. It is just very strong as a love story, as a thriller, a conspiracy story; it’s very well-balanced.”

The script made its way to Anne Hathaway, who signed on to play Claire. The daughter of stage actress Kate McCauley, Hathaway caught the acting bug early, attending the Barrow Group in New York as a teenager. Hathaway “loved the idea of playing a girl who wasn’t living her life to the fullest, who was being ruled by fear but was being shown opportunities, ways to break out. Claire knows she has talent and she’s very smart, but she’s trying to appear adult to the world while at the same time not dealing with her emotional life in an adult way. What a fantastic juxtaposition. And the movie has everything: action, love, personal growth. It’s big and classic yet it feels small, like a character study. I thought it was the best of both worlds.”

Hathaway was also smitten with the idea of working with Garcia after the two met to discuss the script. “I was completely enamored of Rodrigo from our first meeting,” says Hathaway warmly. “We had a very long conversation about the big issues, life and death and romance, integrity, how you live your life. I can be a fairly shy person when you first meet me so to be able to speak so freely with someone was very exciting for me because I thought, well, if we’re just sitting here across a table and I can tell him all these things about myself, I’ll feel very comfortable in character going to these places that we’re talking about. He’s an incredibly lovely, funny, warm, and loving man. I want to make all my movies with him.”

When Hathaway agreed to the project the producing team was thrilled. “Annie has an incredible charisma,” raves producer Julie Lynn. “She has a searing intelligence that the camera can’t help but pick up. It comes through in the talent that she brings to the table and how she delivers her work. It’s an essential part of her being and it works really well for Claire.”

With Garcia onboard and now Hathaway, the project exploded. “We woke up the next morning and the calls started flooding in,” exclaims Matthew Rhodes. “We were slammed so quickly into preproduction that for the first couple of weeks we were still working out schedules. Meanwhile we had twenty people building an airplane.”

Hathaway said yes in November 2006 and by January 2007 the film was shooting. “The crux was that we had a very small window because Anne had her next picture,” says Rhodes. “So it was all hands on deck. But Rodrigo is such a consummate professional and he had spent so much time understanding the characters in the story, he knew clearly what he wanted. That made everything a lot easier.”

With so little time before principle photography, the producers made up a wish list for the remaining cast then set about snapping them up, with a little help from the director. “We were lucky we had Rodrigo,” says producer Keri Selig, “‘because he would just pick up the phone and say, ‘I want to do this with you.’ He was so forthcoming we got everyone we wanted.”

“Everyone” included Patrick Wilson, Dianne Wiest, Clea DuVall, David Morse, and Andre Braugher. Wilson, raves producer Julie Lynn, is “an incredibly versatile actor,” an “adventurer” who “brings a great sense of fun to the character.” Morse is “astonishing,” “a revelation” whose depth “you can’t fully appreciate until you see him work. It’s as if he absorbs the demeanor and the objective of any character that he plays and puts them through his body, and then it just emanates from him as beautiful work.” And Braugher, concludes Lynn, is “so warm and smart you just want to spend your whole day with him. So why wouldn’t Claire?”

With DuVall and Wiest, Garcia drew upon his past relationships with them to lure them onto Passengers. DuVall and Garcia had worked together on Fathers and Sons and Carnivàle, and, while the role of Shannon already existed in Ronnie Christensen’s original script, Garcia “rewrote parts of the character with Clea in mind,” he says. “She’s a very good actor. She’s so natural you feel she isn’t working at all; it just flows from her. But she works very hard, prepares very rigorously.”

Meanwhile, Wiest was working with Garcia on In Treatment, Garcia’s HBO special, but here the director was a little shy about asking a great actor to take such a small role, admits producer Julie Lynn. “He said, ‘She collects Oscars the way I collect hot dogs.’ But all of us, Keri and myself and the casting directors, we said no, let’s get her if we can, let her make the choice. And Dianne said yes.”

Garcia is glad he took their advice. “Diane really brought that role to a completely different level,” he says enthusiastically. “It’s not a role that has many scenes but she really took off with it and made it very funny.”

While the film was being cast, Garcia and the producers headed north to Vancouver, Canada, to begin preproduction. It was winter, cold and rainy, and though the decision to shoot north was a financial one, says producer Keri Selig, “I’m actually really glad we did. Our movie is very gray and rainy so the weather really enhanced the film. Yes, it may have been cold sometimes, but that was the look we were going for. So we lucked out by shooting here.”

Director of Photography Igor Jadue-Lillo laughs when he hears others complaining about the cold and rain. “Everyone was panicking about the weather but I thought the weather was a great, great tool on this movie. We had all these incredible, dramatic skies, and this fantastic light outdoors. Every time it started to rain I was so happy; it just helped out immensely to build this world.”

One thing that set this production apart from so many that have shot in Vancouver was the decision not to hide the city or play it as something else. “When I first came here,” says Garcia, “I said, ‘Why don’t you ever see the city?’ They’re always shooting Vancouver for something else. So I encouraged David Brisbin, our production designer, to show off the city. We don’t call it Vancouver; it’s just where the movie happens. David did a beautiful job creating this world that he called ‘ethereal Vancouver’”—a color scheme of sea green and blue inspired by the surroundings—“lit and designed in a classical thriller way with a very narrow color palette and moody lighting.”

“David Brisbin did an extraordinary job,” adds Lynn. “He takes such care. The minutest little creature sitting in Eric‘s apartment, or the large hull of the downed airplane, it’s all so important to him. And David is interested in how his design serves the movie, not how the movie serves his design. That’s a wonderful thing to have in a production designer. I can’t stress it enough. He’s a great collaborator, a real artist, and a gentleman.”

Highlighting assets, bringing them to the fore instead of treading them into submission, was also the theme on set. “Some directors,” says David Morse, “are the general in command of this huge ship and they feel it all happens by their force of will. They sometimes abuse people in order to get things done. They do good work, and many of them I’d like to work with again, but it’s not always pleasant to be on those films. With Rodrigo there’s no sense of that at all. It’s all of us making this together. He doesn’t make anybody do anything; everybody adores him so they want to do it for him. It’s just a creative environment.”

Producer Julie Lynn, who has worked with Rodrigo on several projects, observes that “what makes Rodrigo a good director is that he’s open to collaboration without giving up his own vision. He asks people to bring a lot to the table; he’s not afraid of new ideas and often will say ‘surprise me.’ But by the same token he’s very confident; people feel very safe and protected. To have someone who’s open to collaboration and yet also has a very determined vision is a great combination. It makes it a pleasure to come to work.”

With only a forty-day shooting schedule, such collaboration and cooperation were essential. “It was a challenge,” admits DOP Igor Jadue-Iillo. “I was shooting non-stop. But I have to say, production wise, whatever we needed we got. We got the cranes, the boats, the pier rigging, and we got there in very good shape. I had two fantastic camera operators, Jim Van Dyke and Gary Viola, and a great gaffer, Drew Davidson—they pushed really hard to have everything ready. The camera department maintained excellent, high standards, and the same with the electrics and the grips. There were no delays. It was absolutely amazing. I couldn’t have been happier. We were lucky to find an amazing crew.”

Where the crew really pulled through most, however, was in the creation and shooting of the movie’s two main special effects sequences, the plane’s descent into chaos and Eric’s meltdown amidst passing trains. For these Garcia relied heavily on the trio of production designer David Brisbin, special effects coordinator Jak Osmond, and visual effects supervisor Doug Oddy of Vancouver’s Technicolor Creative Services.

The crash sequence, which follows the plane from the explosion at high altitude to the moment of impact on the beach, was a complex mix of live shots and computer animation. “We were on set with about a 180 degree wraparound green screen and various stages of plane dressing for the interior fuselage as it tears open, right down to the crash landing on the beach,” explains Doug Oddy. “We probably shot at least a day’s worth of helicopter plates for the various angles of the front of the plane, the side of the plane, the views of the windows, which we stitched together with a digital wing and a digital engine that was burning, along with a digital tear. The whole side of the plane rips open and we watch as the horizon gets closer and closer and closer. That’s one of the unique aspects of this plane crash: every single shot takes place inside the fuselage, right to the point of impact.”

For this unique perspective on the crash Oddy gives sole credit to the director. “When we’re analyzing the effects work, before we’ve had conversations with the director, we see the shots a certain way,” says Oddy. “And we tend to have a generic blueprint in our mind made up of all the different experiences we’ve had. Most of us don’t have the experience of surviving a 737 crash, so we tend to fill it in with what we do know, which is usually other films. This changed completely after talking to Rodrigo; he took it in a totally different direction. He opened it up and energized it. His vision was about the cold reality of what it must be like to carry a plane crash all the way down. In the two minutes it actually takes to lose altitude, what goes on between the people inside?”

In this respect the visual and special effects were designed to function in service of the characters and not as a spectacle in and of themselves. “We wanted the picture to look realistic, not hyper-designed,” says director Garcia. “The stuff that the passengers go through on the airplane is shocking and traumatic, but we kept the relationships between the people going through this, facing what could be their last moments, as the main focus. The idea is not to end with a bang of special effects because that’s just not the story; it’s about the people on board.”

Nevertheless, the crash did prove spectacular, especially to those in the neighbourhood who witnessed the wreckage and huge explosions—and who frantically called 911 before word got out it was a film set scattered across Vancouver’s picturesque Spanish Banks. “We had the entire fuselage of a plane broken and torched all along the beach,” laughs producer Keri Selig. “People walking and driving by thought there was a real plane crash and were freaking out. We alerted the media, talked to everyone, put signs everywhere. And then it turned into this extraordinary day. Everyone from the neighborhood came with their kids and cameras. It felt like we were shooting this with the entire city. Everyone welcomed us.”

The other major scenario for the production team was Eric’s meltdown in the train yard, another complex shot integrating live footage and computer animation. The scene, where Eric stands between two fast-moving trains traveling in opposite directions, was too dangerous to shoot entirely live and also, says, Doug Oddy, “technically difficult to control. The scene called for up to four or five tracks; that’s a fairly busy section of any rail yard. To control the shoot is difficult because so many things are scheduled with those trains, and the location itself is a difficult and dangerous place to shoot because obviously trains are hard to stop—if you have a film crew with cables all over the ground, we’re not the quickest getting out of the way. That, and putting an actor in front of a moving train is maybe something you want to avoid.

“So it was determined that we would help with digital trains. We combined a little bit of green screen work, a whole lot of practical interactive lighting effects for the light that would have been cast by moving trains, combined that with some special effects help—interactive wind and debris for passing trains—and put together a sequence that worked very well. Basically, it involved two moving trains and one static train with Eric standing on the tracks. We shot a series of locked off plates from passes with Eric against a green screen with interactive lighting just on him. Then two background passes with interactive lighting as the grips moved a dolly along the tracks that had lights at the same positions as a train would have.

“We then took multiple exposures of the environment so we would be able to paint backlight for anything that was missed. We cut all those pieces up, built the digital trains, tracked them into the shot, added a little camera movement back in, and we had our finished sequence.”

Oddy makes what was a hugely difficult task seem easy, perhaps because it wasn’t the film’s major effects scenes that excited him the most as the subtle nuances the visual and special effects teams brought to the story. “Some of the effects are rather subtle,” says Oddy, “the development of mood or to help sell an emotion that you’re otherwise not really cognizant of. This is a film where after you’ve seen it once you notice completely different aspects of the film the second time through. And the story has a twist to it. You think you’re seeing one thing but you’re really seeing a reflection of another reality. Being part of that subtle trick is what we embraced the most.”

Everyone agrees it will be the film’s surprise ending that will capture the audience’s imagination, not just for the shock value but because it leaves one with a sense that they just watched a different film from the one they expected. “You’re walloped with this giant punch,” concludes producer Matthew Rhodes, “and then you suddenly realize this is a much bigger love story than you imagined. At first you’re seeing a thriller that keeps you on the edge of your seat and guessing, and then at the end of the film you’re looking back and thinking, ‘I just saw a beautiful love story.’ It’s what we fell in love with and why we made the movie.”

Production notes provided by Columbia Pictures.

Passengers

Starring: Anne Hathaway, Patrick Wilson, Chelah Horsdal, Ryan Robbins, Andrew Wheeler, Robert Gauvin, David Morse, Clea DuVall, Dianne Wiest

Directed by: Rodrigo Garcia

Screenplay by: Ronnie Christensen

Release Date: October 24, 2008

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for thematic elements including some scary images, sensuality.

Studio: Columbia Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $292,437 (7.2%)

Foreign: $3,777,800 (92.8%)

Total: $4,070,237 (Worldwide)