Tagline: He sees dead people… and they annoy him.

Dr. Bertram Pincus, DDS is a big-city curmudgeon, a cynical snob and a self consumed loner who just wants to get away from the teeming masses who surround him in Manhattan. But Pincus is about to have his entire world-view punctured in the wake of a near-death experience. Now that he can see dead people – and literally can’t avoid them no matter where he goes – Pincus has no choice but to interact with these persistent spirits, which opens him up to an even more frightening realization: the only way he’s going to get rid of these pesky poltergeists is to help them.

The whimsically supernatural yet very human concept of “Ghost Town” emerged from the mind of director and co-writer David Koepp, who is one of Hollywood’s most sought-after screenwriters. His writing credits include such globally appealing classics as “Jurassic Park” for Steven Spielberg, “Carlito’s Way” for Brian De Palma and “Panic Room” for David Fincher and, most recently, the summer blockbuster “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.” But he has also won acclaim for several films he wrote and directed himself, including the supernatural thriller “Stir of Echoes” and the suspense-filled adaptation of the Stephen King novel “Secret Window.”

Koepp is highly regarded for his creative handling of the eerie and occult, but he’d never considered taking a ghost story into the realm of comedy until the idea for “Ghost Town” came to him quite suddenly on an ordinary day when he passed a dentist’s office. “I just started thinking about a character who loves being a dentist because he dislikes people and enjoys the fact that they can’t talk to him while he’s working,” Koepp recalls. “I mentioned the idea to my writing partner, John Kamps, and he asked, `What’s the worst thing that can happen to a dedicated loner?’ And naturally, the answer was that it would be if tons of people suddenly could have access to him anywhere, any time.”

And from that notion emerged the concept of the city of Manhattan as a “ghost town,” literally teeming with invisible, needy ghosts who normally can’t be seen by the living until, one day, something goes awry. During Pincus’ routine colonoscopy his life is turned upside down in ways he could never have imagined.

Says Kamps: “When Dave floated the concept of a misanthropic dentist besieged by desperate ghosts, I fastened onto it like a badger and quickly dashed off some thoughts about how I thought the story should go. Then it was dropped for a while due to other obligations. A few months later we found ourselves batting around concepts once again and I asked, `What about your dentist idea? I always loved that one.’ From there we started talking, then outlining, and a thousand Diet Cokes later, `Ghost Town’ was born.”

As Koepp and Kamps continued thinking about Bertram Pincus intermingling with New York’s dearly departed, they realized that his journey was that of a perturbingly anti-social man in serious need of a wake-up call. Says Koepp: “Pincus reminds me of a Warren Zevon song called `Splendid Isolation’ in which a man says he wants to live on the Upper East Side and never go down on the street, and he wants to put tin foil on his windows so he never has to hear or to listen to people. Pincus has chosen the path of least contact with other human beings. He’s had some heartbreak in his past and now he just wants to be left alone. At first, his sole motivation in helping the ghost of Frank Herlihy break up the marriage of his widow is simply the promise that if he does so, Frank will make all the ghosts go away.”

It was Pincus’ personal communication problems that helped shape the story into a fable-like structure, taking it from being just a comic romp through a spirit-filled New York to the tale of a man’s inner transformation through these paranormal encounters. “We wanted to write a comic fable that had some teeth, that would be a bit edgy,” comments Koepp. “There’s a great deal of emotion when you’re talking about the afterlife, grief and loss and we wanted to acknowledge the emotional side of the story as much as its sillier side. You can’t get to one without going through the other, you know? It’s not funny if there are no emotions at stake and it’s not as emotional if you don’t get to blow off some steam by laughing.”

Once Koepp and Kamps decided that the ghosts would steer Pincus back into interacting with the world, they found themselves in an exciting realm for writers – liberated from the physical laws of everyday existence and free to come up with their own set of “ghost rules.” “Traditional ghost rules have been established throughout history,” observes Koepp. “Most of us can’t see them. They can walk through things. They follow the laws of physics, but they can’t affect the environment around them. Those are the general things everyone agrees on, but the way you depict that in a movie is open to your own interpretation. So, I decided early on I didn’t want our ghosts to be about effects, but about comedy and humanity. I wanted to keep them fairly simple. Then we threw in our own bits of lore: e.g., if you sneeze inexplicably on the street, you’ve probably just passed through a ghost!”

Along the way, Koepp and Kamps had a rather big and ultimately poignant epiphany about just what it is that ghosts want from Pincus. “We hit on the idea that traditional ghost stories actually have it all backwards,” explains Koepp. “Ghosts don’t stick around because they have unfinished business. They stick around because the living are not done with them yet, because they aren’t ready to let go. Perhaps they died and left someone mystified or confused, and until the living come to terms with whatever that thing is, they are stuck here.” The ghost of Frank Herlihy discovers he isn’t haunting his former wife Gwen, she’s holding him in limbo until her heart is ready to let him go.

Another decision Koepp made early on was to keep the ghosts visible to the audience throughout the film, similar to what Warren Beatty had previously done in “Heaven Can Wait.” “There is a pretty standard convention where if one character in a movie sees something like a ghost that other people can’t see, you show them talking to that person and then you cut wide and see that they’re talking to themselves. It’s an old gag but it becomes a motif and I didn’t want that. This movie is squarely from Pincus’ point-of-view and, most of the time, the rule is we see whatever he sees… which is ghosts everywhere.”

When producer Gavin Polone read the screenplay for “Ghost Town” (his relationship with Koepp spans two decades, first as his agent and, later, as a producer on “Stir of Echoes” and “Secret Window”), he wasn’t surprised to see Koepp making another unique departure. “Few people have the kind of range Dave has, but with this sort of comedy, I think he has a chance to show a whole other side of himself,” he says. Adds executive producer Ezra Swerdlow, “David has a unique ability to combine elements of great comedy with slightly twisted subjects and turn them into something very appealing, funny and lovely. He’s a very gifted guy.”

Although Koepp has written many screenplays for today’s hottest directors, he always knew he wanted to direct “Ghost Town” himself and had in mind a vision for it before he and Kamps had even completed the screenplay. “I was looking forward to telling this story very simply with the camera and the performances. Unlike some of the films I’ve done in the past which were elaborately planned, this was going to be about my favorite way of filmmaking: working with the actors and shaping and reshaping the material in the telling of it.”

Haunted Into Humanity

To do this, Koepp knew he would need to start with a stellar cast for the three central roles. Over the past few years, Ricky Gervais has become one of today’s most original voices in comedy. A triple Golden Globe winner, two-time Emmy winner and seven time BAFTA Award winner, Gervais has become known for his inimitable brand of sly, endearing, yet self-mocking wit, which first came to the fore with the runaway hit show “The Office.” Gervais co-created the series and starred in it as the infamously smug boss with the incredibly high-pitched giggle (a role which would be played by Gervais fan Steve Carell in the U.S. version of the show).

Called a comic masterpiece by critics and compared to the wild success of such British comedy imports as “Monty Python’s Flying Circus,” the show won numerous awards, including a Best Actor Golden Globe for Gervais. Since then Gervais has branched out from “The Office,” creating and starring in the HBO series “Extras,” another series rife with his trademark “comedy of embarrassing manners.” Among other things, he has also written an episode of “The Simpsons,” penned a best-selling children’s book and taken small roles in feature films such as “Night at the Museum” with Ben Stiller.

But now, with “Ghost Town,” Gervais steps into his very first role as a comedic leading man, playing a loner haunted by an entire throng of ghosts who just won’t let him be. From the minute Bertram Pincus was born on the page, he seemed to be a perfect match for Gervais’ comic sensibility. Says David Koepp: “Ricky mines the humor of the uncomfortable and the awkward as well as anyone. As soon as his name came up for the part, it was impossible not to think of him in it. He’s got this very finely developed comic persona that he’s been working on for 20 years and he brought all that to the role of Pincus.”

Adds producer Gavin Polone: “Not unlike the characters Ricky plays in `The Office’ and `Extras,’ Pincus is a misanthrope who’s always doing ridiculous, sometimes highly unlikable things, but Ricky is so compelling and charming , that you go with him the whole way and, in the end, you find that you’re really rooting for him. He knows where the laughs are, but he also knows where people will get choked up. Funny as he is, some of his finest work in this film are his emotional moments.”

Gervais was drawn to Pincus’ humanity, buried as it might be under two tons of bad attitude. “I think Pincus is a very human man in terms of his emotions, but he’s also a grumpy, wisecracking loner who thinks he prefers it that way, until his mind is changed,” Gervais says of the character. “I liked that he gets a bit of redemption, which is one of my favorite themes. Deep down, he might be a putz but he also has a good heart, one that can only be revealed if he meets the right person. And luckily, he does.”

The comic star also felt that, even amidst the film’s supernatural atmosphere, part of its strong appeal lay in the fact that these characters have a sometimes biting, sometimes poignant reality to them. “Aside from the fact that there are ghosts everywhere, it’s all played very, very naturally and the story’s very much about emotional themes that everyone identifies with: loneliness, loss, jealousy, love,” he says. “The comedy is not about special effects or supernatural gags. It’s about relationships between Pincus and Frank and Frank’s ex-wife and situation they find themselves in.”

Attracted as he was to the role, Gervais was also aware that it would also be by far his biggest acting challenge yet. “It was kind of a baptism by fire for me because I was going straight to a lead part after doing just a few little cameos. It was a daunting prospect, even if I was playing a short, fat man from London, a role I know well,” he laughs.

Co-star Greg Kinnear thinks Gervais’ performance goes far beyond typecasting. “Ricky brought so much life to Pincus,” he comments. “It’s a very difficult thing to get the audience to follow a guy who’s a kind of nasty, horrible jerk and, at the same time, be very funny, witty and even moving. There just aren’t a lot of actors who can pull that off.”

Although he had to leave his home in London for the production, Gervais was especially excited to make a movie that is also a lyrical love letter to New York. “I absolutely adore New York and when you make a film in Manhattan, every single shot can be iconic. It was just so much fun shooting there.”

And truly, upper Manhattan, with its architecturally distinct buildings, Central Park and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, function as a supporting character in the film. The ghosts are as at home in this setting as the living, breathing characters. The city seems full of possibility. Every time a character steps off the curb, anything can happen – he can be hit by a bus, pursued by ghosts or run into someone who will change his life forever.

Ghost With an Agenda

Bertram Pincus’ newly haunted life is changed by one harassing ghost in particular: Frank Herlihy, once a handsome, debonair but decidedly unfaithful husband who, after losing his life in the blink of an eye, now hopes to finally do the right thing by his widowed wife. But that means he’ll have to be pushy and obnoxious and use every last remaining bit of his New York attitude to pester Pincus into helping him. To play Frank, the filmmakers sensed they would need someone enormously likeable, yet hilariously fallible. No one fit that bill better than Academy Award nominee Greg Kinnear, the actor who has rocketed to leading screen stardom with roles in some of the biggest comedy hits of the last few years, including “As Good as It Gets” and “Little Miss Sunshine.”

“When we started talking about Greg, I watched some of his past performances and I was really taken with that wonderful scoundrel quality he possesses,” says Koepp. “He’s able to project some pretty reprehensible qualities in a very lovable way. For me, Frank Herlihy was like a character Cary Grant would have played 50 years ago, and Greg was the perfect casting choice for that.”

Kinnear was drawn to Frank Herlihy’s dilemma as a ghost who wants to be released from his earthly bonds, and thus becomes a kind of spectral Cyrano to Pincus, trying to coach this bumbling misanthrope into luring his ex-wife away from her fiancé. “Frank is a man with unfinished business,” Kinnear observes. “And what’s compelling about the film’s premise is that you have two men – one dead and one alive – who both have unresolved life issues.”

He continues: “I thought it was the kind of script that just dances off the page, and I enjoyed that you have these characters who might have some rather unsavory qualities but ultimately reveal their underlying decency. There are these little ways in which the characters change and, hopefully, that will resonate with the audience.” Like Ricky Gervais, Kinnear loved the idea of shooting on location in Manhattan. “If there was ever a movie that really needed to take place in New York City, this is the one,” he says. “New York has so much life in it, yet it’s so old and filled with history, you just couldn’t imagine being anywhere else to shoot this story of ghosts looking for redemption.”

Another draw for Kinnear was the chance to work with Téa Leoni – but he notes that he didn’t exactly do so, since his character was never even so much as visible to her. “I’d been hoping to work with Téa for a long, long time and I just want to go on the record right here and now that this doesn’t count,” he jokes. “Her character never even sees me because I’m dead. So, I’m still looking forward to working with her.”

From Spectral to Screwball

At the center of “Ghost Town” is Frank’s widow, the brilliant, if mummy obsessed, archeologist Gwen. To play Gwen, David Koepp went in search of something quite rare nowadays – a classic screwball comedienne, someone with an inner elegance and intelligence who could also shine in the most outrageous and comical situations. He found that in Téa Leoni, whose recent comic roles include “Spanglish,” “Fun with Dick and Jane” and John Dahl’s “You Kill Me.” “Téa is one of our most gifted screen comediennes,” says Koepp. “David Denby in The New Yorker compared her to Carole Lombard, which I think is totally appropriate. In `Ghost Town’ she plays an Egyptologist, which is a great character in a comedy about death, someone who is fascinated by these very old, very dead people from ancient times, and Téa makes her entirely believable.”

Gwen begins “Ghost Town” still very much recovering from both the shock of her husband’s death and the revelation of his rank infidelity. Unsettled as she is over the past, she’s certainly not expecting to ever hear from Frank again, especially from the afterlife through a blundering dentist – a situation Leoni found irresistible. “Gwen’s at this point in her life where, after everything she’s been through, she feels like she never wants to miss the opportunity to say what she needs to say to anyone again,” says Leoni. “She’s very direct, which makes her very funny and a little bit spastic.”

In addition to the sparkling comic repartée she has with Ricky Gervais, Leoni loved that “Ghost Town” never loses its wry edge. “I think this whole idea of ghosts sticking around because the living are holding them here is a very romantic notion. There’s something moving about the idea that your sense of loss holds someone near and that you can give them ultimate peace.”

Once on the set, Leoni was further inspired by the no-holds-barred tone set by Ricky Gervais. “His comedic sense is uncanny,” she says. “He has a flavor to his comedy that reminds me of Woody Allen, where he’s this poor sod in the middle of a world gone mad, yet you’re fascinated to see the world through his eyes.”

Leoni adored working with Gervais but far more challenging was her co-star of the canine kind: a 200-pound Great Dane, who portrays Gwen’s “puppy.” “He’s really the largest animal I’ve ever seen that could be called a dog,” she laughs. “He’s got jowls the size of trench coats, and when I walked him, he literally pulled me out of my shoes! But I loved the scenes with the dog because they set a wonderful, kind of fairytale tone for Gwen.”

When it came to working with Kinnear, Leoni had a different sort of challenge to meet. “It’s very difficult to work with an actor you can’t look at or even acknowledge is there, and sometimes, okay often, I couldn’t help but look at Greg,” she notes. “He is so snappy and funny – and with the character of Frank, he also ultimately shows a very vulnerable male side, which is what Gwen responds to in him.”

Fiances, Surgeons And Phantasms

Another character key to the comedy of “Ghost Town” is Gwen’s fiancé Richard – an almost painfully sincere, maddeningly decent human rights lawyer who seems like a dream but is believed by Frank to be a no-good liar who is hiding something, much like Frank did when he was alive. To play the unassailable Richard, the filmmakers chose Billy Campbell, best known for his work on television, including his Golden Globe-nominated role in the hit series “Once and Again.” Campbell transitions smoothly back to the screen in a role Koepp calls “the Dean Martin part” – the suave straight man balancing out the silliness going on between Ricky Gervais and Téa Leoni. Campbell had a blast in that unique position. “For me it was like being back in improv years ago. It was some of the most fun I’ve had,” he says. “Ricky is just a ball of live energy, his mind is so active, so quick. It took everything I had to keep up with him. And to look at Téa, you wouldn’t immediately make the assumption that she’s a brilliant comedienne, but she is. Along with Greg Kinnear, I often couldn’t believe I was in the room working with these great comedians.”

The distinctively layered comic style of “Ghost Town” also appealed to Campbell. “It’s a comedy but it’s also a wry commentary on loss and the way we think of the departed,” he notes. “It gets to this idea represented by an Einstein quote seen in the film that a life not lived for others is not worth living, and I think the brilliance of David Koepp is that he keeps the film very smart and funny without wearing its themes on its sleeve. The story can be warm and touching but mostly it’s dead funny.”

Producer Gavin Polone notes that Campbell’s straightness in the role only amps up the humor. “Billy makes it so much funnier because he’s not a jerk but somebody you can’t help but really like. It sets a much higher bar for poor Pincus to clear,” he says.

Meanwhile, for the film’s smaller roles, Koepp set out to find a roster of equally memorable actors. These include stars of stage, screen and television Dana Ivey as the disgruntled ghost Mrs. Pickthall and “Saturday Night Live” star Kristen Wiig as the surgeon whose colonoscopy of Bertram Pincus leaves him reeling in a most unusual way.

Says Ivey: “I was drawn to this story because it takes such an unusual, funny situation and brings so much humanity to it. It’s a story full of human foibles and when we laugh at it, we’re laughing at ourselves really. And what I loved about the ghosts, like Mrs. Pickthall, is they’re not decayed or shrouded, they’re very alive in their own sphere and we just played them as real people.”

Wiig says it was her admiration for Ricky Gervais that drew her to “Ghost Town.” “I think he’s really brilliant and I’ve always wanted to work with him,” she comments, “so this was like a dream come true for me. Working with Ricky, you find yourself doing really funny things that you didn’t expect to find. We definitely went by the wonderful script, but Dave Koepp also let us play and find our own way with our characters. The whole journey was really fun because the idea of lampooning that moment of death struck me as so intriguing. I always think the best surprise is to find something truly hilarious in something that really doesn’t seem funny at all.”

Finally, the casting turned to the rest of the ghosts, a diverse bunch befitting Manhattan’s afterlife. “It was very important to have terrific actors in each of the ghost roles because even though you only see these characters for a short time, you have to really like them and you have to hope that Ricky can help them with their dilemmas,” explains Gavin Polone. “Our casting directors, Pat McCorkle and John Papsidera, did an amazing job of assembling a fantastic group of ghosts.”

Designing “Ghost Town”

Joining the great pantheon of films that pay heartfelt homage to the magic and romance of Manhattan, “Ghost Town” provides a surprisingly fresh view of the metropolis – as colorful, sophisticated and beautiful as ever, yet crowded with a whole subculture of the recently departed from all walks of life who exist just beneath the visible surfaces of the city.

There was never any question “Ghost Town” would be shot on location. “There’s really no alternative to New York,” observes executive producer Ezra Swerdlow, “and we felt very fortunate to be able to make use of the city’s great museums, restaurants, streets, Central Park, the entire Upper East Side, and inside Fifth Avenue apartment buildings. It gives the film that unmistakable New York feeling. I think people like the truth of a New York movie where they see their favorite places, where the streets all tie-in together and when you turn the corner, you’re right where you should be.”

The task of using Manhattan’s iconic locations in new ways for the film fell to an artistic team that includes director of photography Fred Murphy, who previously shot Koepp’s “Secret Window” and “Stir of Echoes,” production designer Howard Cummings, who collaborated with Koepp on “Secret Window” and “The Trigger Effect,” and New York-based costume designer Sarah Edwards, who was working with Koepp for the first time on “Ghost Town.”

Fred Murphy brought a rich feeling to each carefully drawn frame of the film. Says Swerdlow: “Fred is an artist, a truly sensitive, visually experienced filmmaker who is just this bedrock of professionalism, yet also has a great eye for making people look good, how to light big shots, how to light intimate shots and how to light up New York City at night.”

Murphy and Cummings began collaborating early on with Koepp and came up with a visual game plan. “We were very inspired by New York in autumn, the changing seasons and the color of the leaves,” recalls Cummings. “We made the decision to start the film at the end of summer and move into fall colors more and more as the story goes on. We also knew that we wanted to preserve a more pristine view of New York, with beautiful Beaux Arts buildings and people dressed the way New Yorkers dress.”

While Cummings worked extensively with real locations, he also built several sets at the Steiner Studios in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where he brought Pincus’ and Gwen’s very disparate apartments to life. The magic lay in the realistic details he brought to both. “Both Pincus and Gwen are living in a doorman building on Fifth Avenue but that’s all they share in common because their apartments are total opposites,” he explains. “Pincus’ apartment is very neat and orderly and has remarkably little excitement in it. He doesn’t even have a view of the park. Gwen’s couldn’t be more different: full of color and light, with lots of eclectic things and objects she’s brought back from her travels all over the world.”

Cummings similarly played with contrasts in Pincus’ dental office, site of many comic moments amidst the inescapable tension of drills and syringes. Here, he played Pincus’ purposefully ultra-bland décor off that of his partner, the personable Dr. Prashar (played by Aasif Mandvi), whose much cheerier office, lined with family photos and inspiring posters, is stubbornly avoided by Pincus until he has his epiphany.

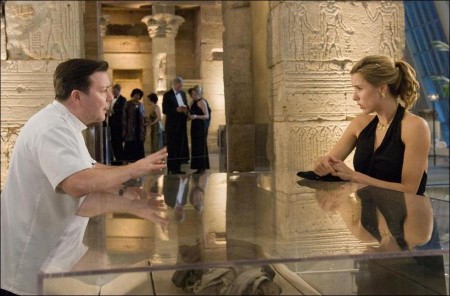

But for Cummings, the most exciting sets of all were legendary New York locales, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Central Park. At the Museum, the filmmakers shot at the spectacular “Temple of Dendur,” an impressive backdrop for Gwen’s lecture about her latest mummy discovery. “It’s a very dramatic location,” he muses. “I think it gives our movie some scale and suggests that Gwen is gaining worldwide stature as an Egyptologist. It’s also another great slice of New York.” Adds Swerdlow: “Dave always wanted to shoot in the Temple of Dendur. It’s a gem of a location but was one of the most daunting elements of the film.”

The big challenge at the Met was time – as the production had a very limited window in which to move in a giant crane, shoot the scene and get out before hundreds of visitors would show up to see the famed Temple during operating hours. “Shooting at the Met is a big commitment,” says Swerdlow. “You can’t make a mistake because you really can’t go back. So you’re working under a lot of pressure. But we got lucky and everything looked great.” To give the production further peace of mind, the equally beautiful Egypt Gallery at the Brooklyn Museum was used to “stand in” for the Met in several scenes.

Gwen’s prized mummy, named Pepi III in the film, the object that first brings Gwen and Pincus together in an unlikely alliance built on dental bacteria, was based on the mummy of Ramses I, the founding pharaoh of Egypt’s 19th dynasty. “Using research on Ramses I, we started with a human skeleton then added layers of dried, shriveled skin made out of latex and paint,” explains Cummings. “It looked so real it fooled some people in the museum.”

If the Metropolitan Museum brings to life New York’s cultural side, the scenes in Central Park evoke its beauty and romance. While the park has been seen in countless motion pictures, Cummings wanted to use areas not usually seen on screen, including the Literary Walk, a tree-lined area at the Southern End of the Mall featuring statues of Shakespeare, Sir Walter Scott and Robert Burns. “I have always loved the Literary Walk; there’s something very old and unique about the way the trees intertwine and the way the benches look there. It has a very introspective appeal,” says the designer.

The New York of “Ghost Town” comes to life not just in the locations and photography but in the characters’ clothes as well, which were designed by Sarah Edwards, who most recently designed the contemporary, corporate-world clothing for the Oscar®-winning thriller “Michael Clayton.”

Edwards began her work coming up with a less-than-charismatic look for Pincus – a man whose life revolves largely around dentistry and being solitary. “The idea behind Pincus was to have a simple austerity to his look,” she explains. “The colors are drab, lots of black, grey and tan. Even his dental coat was completely re-cut for that specific Pincus look. But as the story progresses, we see more and more of a departure. The colors become a little warmer, and even his hair loosens up a bit.”

Greg Kinnear, on the other hand, required just one snazzy outfit throughout. “Greg’s character died in a tuxedo and that’s what he wears: a bow tie and suspenders, with beautiful cuff links. He forever looks like he’s going to a party at five in the morning. Greg was a trooper and really made it work and Canali provided a tux that was very clean, not too flashy, so you can look at it throughout the entire film.”

The much more effusive wardrobe for Gwen was particularly fun for Edwards. “Gwen is a wonderful character, so sophisticated and smart,” she says. “David didn’t want a lot of ethnic stuff that might scream `I’m an Egyptologist on safari’ or make her a caricature. Instead, we wanted Téa to look both attractive and real. And she was wonderful to dress because she was so collaborative. When it came to Gwen’s gown for the party at the Met, we tried and tested about 25 different garments. We finally arrived at something very classic and very New York… and it looked perfect on her.”

But the biggest creative thrill of all for Edwards was designing the clothing for those who can no longer change their clothes – the throng of recently departed ghosts who are trapped in their final outfits, whatever they may have been. “The ghosts were very different than your usual ghosts because they’re not really ancient, there are no Victorian or Renaissance ghosts. The earliest ghost David felt would still be held here by living memories would be from maybe the 1940s,” Edwards explains.

She continues: “David wanted a broad mix of ghosts and we went through files and files of pictures. We have an old couple from the `60s, a World War II nurse, a Serpico-style cop from the `70s, a poor naked guy. We also have a hardcore biker, a tennis player and some ladies who lunch. But they were all just sort of scattered in. He didn’t ever want one particular look to take over the whole frame.”

Ultimately, the ghosts, like everything else in the film, would come to life largely through indelible performances. This was at the heart of what David Koepp was going for in “Ghost Town” and the reason why he kept the film’s visual effects to a surprising minimum for a supernatural comedy.

“We did not want this to be an effects movie but we wanted the ghosts to be handled in a very elegant and fun way,” explains Ezra Swerdlow. “The main ghost effect we use is that ghosts can pass through objects, including people and city buses and buildings. We wanted to do that in a way that wasn’t just a series of simple transparencies, so that was where we concentrated our computer work.”

Beyond those few seamlessly integrated CG sequences, everything else went back to the strength of the story and the skill of the actors. Sums up Gavin Polone: “At heart, `Ghost Town’ is a very, very funny film about people and about our biggest human emotions: loss, guilt, yearning and love. That’s why we all agreed we didn’t need to overload it with a lot of visual or special effects because, in the end, that’s not at all what the film is about. All the effects in the world are useless if you don’t feel that special connection to the characters.”

Production notes provided by DreamWorks Pictures.

Ghost Town

Starring: Ricky Gervais, Téa Leoni, Greg Kinnear, Billy Campbell, Kristen Wiig

Directed by: David Koepp

Screenplay by: David Koepp

Release Date: September 19, 2008

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for some strong language, sexual humor, drug references.

Studio: DreamWorks Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $13,111,033 (70.3%)

Foreign: $5,541,174 (29.7%)

Total: $18,652,207 (Worldwide)