Tagline: Laugh like your country depends on it.

In summer 1977, the televised David Frost / Richard Nixon interviews attracted the largest audience for a news program in the history of American TV. More than 45 million viewers-hungry for a glimpse into the mind of their disgraced former commander-in-chief and anxious for him to acknowledge the abuses of power that led to his resignation-sat transfixed as Nixon and Frost sparred in a riveting verbal boxing match over the course of four evenings.

Two men with everything to prove knew only one could come out a winner. Their legendary confrontation would revolutionize the art of the confessional interview, change the face of politics and capture an admission from the former president that startled people all over the world… possibly even including Nixon himself.

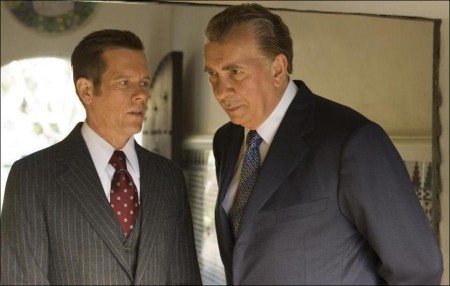

Now, Academy Award-winning director Ron Howard (A Beautiful Mind, Cinderella Man, Apollo 13) brings to the screen stage- and screenwriter Peter Morgan’s (The Queen, The Last King of Scotland) electrifying dramatization of the battle between Richard Nixon (Frank Langella, Good Night, and Good Luck.), the disgraced president with a legacy to save, and David Frost (Michael Sheen, The Queen), a jet-setting featherweight television personality with a name to make, in the untold story of the historic encounter that changed both: Frost/Nixon. Re-creating not only the on-air interviews that captivated the nation, but weeks of around-the world, behind-the-scenes maneuvering and negotiations between the men and their opposing camps, the film explores the long-untold story that led to the ultimate face-off in the court of public opinion.

For three years after being forced from office, Nixon remained silent. But in 1977, the steely, cunning former commander-in-chief agreed to sit for one all-inclusive interview to confront the unanswered questions of his time in office and the Watergate scandal that ended his presidency. Nixon surprised everyone in selecting Frost as his televised confessor, intending to easily outfox the breezy British showman and reclaim his status as a supreme statesman in the hearts and minds of Americans.

Likewise, Frost’s team harbored doubts about his ability to hold his own against Nixon. As cameras rolled, a charged battle of wits ensued. Would Nixon evade questions of his role in one of the nation’s greatest disgraces? Or would Frost confound critics and bravely demand accountability from the most skilled politician of his generation? The encounter would reveal each man’s insecurities, ego and reserves of dignity-as both ultimately set aside posturing in a stunning display of unvarnished truth.

Playing a key role on Nixon’s team is Kevin Bacon (The Woodsman, Mystic River) as his chief of staff, Colonel Jack Brennan, the fierce guardian who guides Nixon through the strategy of the interviews. Two brilliant consultants would handle Frost’s education on the 37th American president. Oliver Platt (Casanova, Kinsey) stars as Frost strategist (and executive editor of the interviews), veteran reporter Bob Zelnick, and Sam Rockwell(Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, Matchstick Men) plays Frost’s acerbic writer and Nixon critic, author and university lecturer James Reston, Jr. Both were motivated to expose the “real” Nixon and operated as the architects of Frost’s strategy, while Frost took on the tasks of selling rights to the interviews, securing a broadcaster and studying his adversary.

Supporting players in the cast are a winning assemblage that includes Rebecca Hall (The Prestige) as Frost’s girlfriend, Caroline Cushing; Toby Jones (Infamous, The Painted Veil) as Nixon’s agent, Irving “Swifty” Lazar; and Matthew MAcFadyen (Pride and Prejudice, Death at a Funeral) as Frost’s British producer, John Birt.

Imagining Frost / Nixon: From Interviews to Stageplay

Stage- and screenwriter Peter Morgan was first drawn into the world of David Frost and Richard Nixon in 1992. He had seen a televised biography of the broadcaster and was fascinated by what Frost had been able to accomplish with his infamously canny subject during 1977’s series David Frost Interviews Richard Nixon. As he relayed to Richard Brooks in a Sunday Times piece in July 2006, the writer was “driven by this image I had of these two men. The glamorous Frost, 54,000 feet up in the air, going backwards and forwards over the Atlantic on Concorde. And Nixon, a man really living in a cave. A man who found life very hard.”

Long interested in examining the humanity of complex world figures such as Queen Elizabeth II, Idi Amin and Henry the VIII, Morgan would research not only former president Nixon, but also one of his greatest (and most unexpected) antagonists: David Frost, the playboy of British television whose entire credibility and career rested on the unique opportunity of extracting a confession during the interviews.

Morgan was intrigued by the contrasting lives of the two and believed that their story would lend itself well to a stageplay format. He felt that if he were to design the square off, he would need to wrap the interviews as “an imminent gladiatorial contest where the only weapons allowed were words and ideas.”

Of his research into the subjects, Morgan observes, “I could see both camps were preparing one another in the way that chess adversaries or boxing adversaries prepare-very strategic. I thought it would be possible to write interview scenes with the actual words that were used, but somehow sew them together to construct something with the ups and downs of a really satisfying contest.”

In studying their social interactions, Morgan discovered something that would serve him exceptionally well as a dramatist: each man was an opposite of the other in fundamental ways. He reflects, “If you separate Nixon the human being and Nixon the politician, you can’t help but feel for someone who found life so difficult-communication, friendship. Then you look at someone like Frost who finds life, certainly socially, very easy; he’s very naturally gifted at communicating with people, making friends, being liked. Nixon was quite the opposite, really-suspicious of people, wounded, probably didn’t have many close friends, an unhappy marriage-a very lonely man.

The writer believed that the showman best known for puff pieces and fawning journalism was also misunderstood… and quite underestimated by his then contemporaries. “Frost had a great intellectual insecurity,” he shares. “He just wasn’t taken seriously.” Of Frost’s interviewee, he adds, “The one thing you could never lay at Nixon’s door is the charge that he was stupid-he was a formidable thinker.” Morgan took these ingredients and “became excited to bring these two people together.”

When creating the play, Morgan engaged in extensive conversations with many who had been involved in the original interviews, including Sir David Frost and others who would ultimately be portrayed on the West End theatrical stage where Frost / Nixon debuted. As he offered to Gareth McLean in his interview with the Guardian in August ’06, “Everyone I spoke to told the story their way. Even people in the room [at the time of the interviews] tell different versions. There’s no one truth about what happened off camera or behind-the-scenes during the period covered in our story. I felt very relaxed about bringing my imagination to the piece.”

Understanding the Medium: Television Plays Its Role

As personified by Frost, a recurring theme of Morgan’s developing play was the growing influence and foggy responsibility of the fourth estate in shaping public opinion, as relevant an issue today as it was in the post-Watergate era when the Frost / Nixon interviews were taped, and even earlier in American history.

Since Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first Fireside Chat in March 1933, topics from bank crises and national security to the latest war and/or conflicts have been readily available for dissemination to an eager American public, and inspiring works of historical fiction. While politicians have long sought to control the medium by delivering the perfect message point, with the market penetration of television they had a new method with which to sway opinion. That concept offered Morgan much drama from which to draw.

Taking a cue from the camps that surrounded Frost and Nixon before the infamous interviews, Morgan delved into further research about how the burgeoning medium created the public personalities of Frost and Nixon. What he found was enlightening, particularly on just how television dictated and was manipulated by both men.

While television had been Nixon’s adversary many times throughout his career, it had also been an invaluable ally in his rise to power. In September 1952, he had used it masterfully during the so-called “Checkers Speech,” a sentimental plea during the time he was embroiled in an ethics scandal that threatened his candidacy as the Republican nominee for the vice presidency. Arguably, he came across austere and plainspoken… a solid product of his Quaker upbringing. And upon Eisenhower’s request, in March 1954 the then vice-president brilliantly manipulated the media to make a name for himself during his powerful speech in the Army-McCarthy hearings, skewering a man some previously felt above reproach.

It would not stay Nixon’s ally forever. The 1960 televised presidential debates between Kennedy and him marked the beginning of a new era in which politicians could present their message and pundits feverishly analyze it. Nixon, sweating profusely and with running makeup, was soundly thumped as the dashing JFK remained calm and collected. Candidates would now be judged not only on their relevant experience for the job at hand, but their comparative telegenic appeal.

That hard lesson would not prove fruitless, and provided rich history for Morgan. Nixon rebounded to win the nation’s highest office. Throughout his subsequent presidency-from his July 1969 meetings with President Nguyen Van Thieu in South Vietnam to his February 1972 historic outreach to Asia with Chinese Party Chairman Mao Zedong-he worked hard to become telegenic and approachable. And then came Watergate.

The impact with which television hammered Nixon’s Watergate sins into the public’s consciousness overshadowed the successes of his two terms in office. As the specifics of those crimes which led to his resignation on August 9, 1974, faded in the collective memory, the former president-through his agent, Hollywood legend Irving “Swifty” Lazar-began looking for a way to bring his accomplishments back into the American consciousness. Nixon would give that most powerful medium one more chance to serve or betray him. But he would set the ground rules and choose his perceived weakest opponent.

David Frost began his career on television as a young comedian whose buoyant enthusiasm was a wicked counterpoint to the dire events reported on the faux news program That Was the Week That Was. This groundbreaking satire fell victim to the same government officials it lampooned when, during an election year, the BBC cancelled the show because it might be an “undue influence.” Frost next became part of an American version of the program that ran from 1964 to 1965. It was his first taste of fame in the U.S. and it made him want more.

In the late 1960s, Frost headlined The Frost Programme for British ITV. It was a precursor of the “trial by television” shows that would later become a genre in both news and reality formats. It was also a major change for the erstwhile comedian: Frost came to be taken seriously as an interviewer. However, the lure of fame in America drew him back to the world of entertainment. 1969-1972 saw Frost become host of a celebrity talk show called The David Frost Show, featuring guests ranging from Richard Burton to the Rolling Stones. Then the show was dropped and Frost was unable to find another American network that would hire him.

He hosted a celebrity-driven chat show in Australia, but longed both to get back on the air in the U.S. and to be regarded with gravitas. When he hit on the idea of interviewing Richard Nixon, he had to convince a number of people that he was the man for the job. But it was, ironically, his reputation as a “lightweight” that lured his intended subject to agree to the series of historic interviews.

When the special aired, politicians more than anyone realized the reductive power of Nixon’s close-ups, and how that pressure led to his confession. From that moment on, television would be used to not only deliver their messages, but, better still, a personality package-often in place of anything substantive.

The maturation of the medium and how TV would forever influence politics fascinated Morgan, and it would become the playwright’s throughline for this work. Morgan was keenly aware that, in shaping this story, television as equalizer would be examined. As he documents, these two men rolled the dice-with promises of ruin or resurrection-and gave it everything. Nixon relied on his ample skills as a negotiator and statesman…Frost on his ability to have others open up and reveal to him what they weren’t certain they wanted to share. And that made for good TV.

The series of Frost / Nixon interviews, according to writer James Reston, “remains the most watched public affairs program in the history of television,” with a viewership of more than 45 million. It would be the last major appearance on television for Richard Nixon before he died in April 1994.

Imagine and Working Title: Bring the Play to the Screen

Morgan’s play Frost / Nixon premiered at London’s Donmar Warehouse on August 10, 2006, under the direction of Michael Grandage. One of the country’s leading theater critics, Benedict Nightingale of The London Times, praised, “Welcome to Michael Grandage’s absorbing production of a play that last night did two unexpected things. It showed David Frost shedding his genial, tabby-cat image, finding his claws and becoming as tigerish as any Humphrys or Paxman. And it managed to win a little sympathy for his unlovable prey, Richard Nixon… As often with docudrama, you’re not sure how far Frost/Nixon is to be trusted, but there can surely be no doubting the authenticity and power of its climax… Factual, fictional, it makes for riveting drama.”

Cast as Richard Nixon and David Frost for Morgan’s play were Frank Langella and Michael Sheen. The two men created their roles in the production’s widely honored debut on London’s West End and revisited their work on Broadway. For his portrayal of the president, Langella would be lauded with the Tony Award for Best Actor in a Play. These actors had grown intimately familiar with the affectations and eccentricities of their historical characters. Just as important, they had studied the relationship that formed between their counterparts during their brief, intense on-air interactions.

Of utmost importance to the project was the endorsement of Sir David Frost. Naturally, the journalist had rights to the interviews and any creative interpretation of them, including stageplay. But to ensure Frost/Nixon was seen as a dramatized event, not an authorized biography/documentary, Frost understood he would not have editorial control of the content. Rather, he was asked to provide guidance of the actual events and historical reference. He admits he was quite satisfied with the results.

Frost was most concerned that the story not be a verbatim replaying of the events, but one in which the story was told fairly. He reflects of the first time he saw Sheen portray him: “For about 20 minutes, it was rather odd watching someone play you. And then I really started to think of it not as me, but as the Frost character. Because I was more interested in the content and wanting to see that the content was done justice.”

The journey that would take this stageplay to a screenplay began when two American filmmakers came to the West End to see Morgan’s work. “I think it all started on the second preview of the play in London, when one particular director and producer just saw it and they immediately rang up, and this escalation of interest happened. Everybody seemed sure it would make a film,” recalls Morgan. He initially believed Frost/Nixon, however, would never translate into a script. “I’d written screenplays, and I’d done my best to write this in a way that it could never be adapted. I’d done things that I thought were so theatrical it would condemn it to a theatrical life, and that’s what I wanted.”

The author’s best laid plans, in this effort, went gratefully astray. The filmmakers who propositioned Morgan about adapting his play were Ron Howard and Brian Grazer of Imagine Entertainment, partnering with Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner of Working Title Films in a deal that bested a number of directors and producers eager to option the project. The four were impressed with “the character-driven story that’s all about the intensity of the conflict between these two men,” says Howard.

Of his excitement for the material, Howard explains, “While these interviews were watched by millions of people all over the world, the real drama of this event was a dynamic between the two men that very few people understood. It was a battle of wits in which each man was fighting for his professional life and only one could walk away the winner. It came down to the evasive skills of Nixon, versus Frost’s ability to get people to talk to him.”

The fact that it was written for the stage didn’t bother Howard, as he knew that Morgan’s story could be translated into a different medium. He reflects, “I wasn’t as worried about opening it up visually as I was about making it ring true and exist in a world that we relate to.”

During these discussions, Frost / Nixon-due to its successful run in London-opened at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre on Broadway in April 2007, and played to sold-out houses. Grandage received a Tony and Drama Desk nomination for his helming of the Broadway production. Frost / Nixon also earned Tony and Drama Desk nominations for Best Play and Frank Langella won both the Tony and Drama Desk Awards for Best Actor in a Play. For his Broadway stagework, Michael Sheen received a number of critical nods, including a nomination for a Distinguished Performance Award from the Drama League. For his British debut, the actor received nominations for Best Actor from the Olivier Awards and Evening Standard Awards.

While his play was roundly lauded, however, there was more legwork ahead for Morgan as he revisited the world of Frost and Nixon for the screenplay Imagine and Working Title commissioned. He recalls, “For the play, I’d flown to Washington and met with Jim Reston, Bob Zelnick. I’d met with Kissinger. It was very East Coast.”

To research the screenplay, he’d need to extend his travels. “I’d never been to the West Coast locations,” Morgan shares. “I’d never actually gone to where it all happened-Orange County, California. I’d never been to the Nixon Museum or the Nixon Library, the Nixon Foundation. I hadn’t seen that helicopter; I hadn’t met people who’d worked for him. I hadn’t been to Republican Orange County; I hadn’t been to San Clemente. It was really exciting to do all that, and I did all that with Ron once he’d committed to making the film.”

The end product was a script that Morgan formerly thought impossible to make. He states, “The force of these peoples’ convictions made me think, you know, maybe there is a film in it.” The director and producers were quite pleased with the results.

“What Peter Morgan has given us, first in his play and now in his screenplay,” commends Howard, “is so rich and dimensional. It’s funny; it’s smart, but ultimately it’s suspenseful and very intense.”

Most surprised at the translation of his words was Morgan. The author says, “I love how Ron has managed to take some challenging, adult material and make it accessible. He has the ability to democratize a story that could otherwise have been too complex and make it into something you really want to go to the cinema to see when it comes out. And I very much wanted that. I did not want this to remain a sort of artsy-fartsy, rarified piece.”

Frost / Nixon’s scheduled Broadway closing was on August 19, 2007, approximately four months after its opening. The movie began principal photography five days later.

Gentlemen, To Your Corners: Casting the Film

There was no doubt from the filmmakers that Frank Langella and Michael Sheen should remain Richard Nixon and David Frost for the filmed version of Frost / Nixon. “It was a given that Michael and Frank would inhabit the roles,” offers director Howard. “It’s impossible to imagine two other actors bringing the kind of research, preparation or chemistry that the two of them offer. For almost two years, they have lived as Frost and Nixon.”

Langella wanted his performance not to be mimicry of Nixon, but a dedicated interpretation of a fallible man. The challenge for him was that, unlike Sheen’s reference, Nixon is no longer alive. “I was determined not to do an impression,” Langella states. “I looked in him for the thing I look for in every character I play: What is his soul about? What is his inner heart and mind about? You really can’t play a `politician,’ a `musician,’ a `serial killer.’ You don’t play the title. Everybody’s a human being and everybody has a soul, a heart and a mind.”

Of his attraction to the role, Langella continues, “Richard Nixon is close to the most fascinating man I’ve ever had the privilege of portraying. I became obsessed with him and obsessed with the inner demons in him. I liked the fact that Nixon was not an everyday guy, as I like that about all the politicians of that period. They were irascible, difficult, funny looking, bizarre guys and they revealed a lot more of their idiosyncrasies than today’s do.”

There was something surreal about seeing Nixon come to life through Langella’s performance, acknowledges Academy Award-winning producer Brian Grazer. “From the ever-present low growl in his voice to the slight grin that Richard Nixon could flash, it was fascinating what Frank could do. Under a different actor’s care, the role could have easily become a cheap impression of Nixon. But he incorporated those iconic affectations we know Nixon had while bringing this deep sensitivity to unguarded moments. When you watch Frank, the actor vanishes and you simply see a terribly conflicted man who has, essentially, been dethroned.”

Routinely lauded by critics and audiences alike during the play’s run, Langella’s biggest compliment would be provided by his character’s nemesis. David Frost agrees: “He doesn’t look like Nixon, but you feel he’s Nixon. Some of his gestures may not be remotely Nixon gestures, but they feel like Nixon gestures. So he transcends accuracy; it’s more than accurate in a way.”

Transitioning the role from stageplay to film presented another set of challenges for Langella. He offers, “When you take a character from a play and bring him to the stage, you have to fight a very particular kind of acting monster. I did it 360 times. I had an inner rhythm going that was so part of my being that even I didn’t know. [In front of the camera], it became very exciting to me to throw away and metaphorically open the window and toss out the stage performance-keep all the elements of it that worked but then bring a fresher approach to it.

As with Langella, the transition for Sheen was a long study in behavior. As he moved the role to film, however, he grew even more comfortable in Frost’s skin. “I’ve lived with this character for over a year, and the basics of the way I see him didn’t really change from stage to film,” he notes. “It’s just about being specific to your audience. I suppose on stage you play to the audience in the room and on film you play to the camera. The big difference on stage is that you have to pretend you’re on an airplane or pretend you’re at the Western White House, etc. For the film, I only had to be there.

“Playing a character who exists in real life obviously brings two sets of responsibilities,” the actor continues. “You have the responsibility that you always have with any character you play-to the writer, to the story. You’ve also got the responsibility to the real person. But inevitably, there are elements of the real person that are going to help the story more than others. If we made Frost look overly competent, then the tension and the suspense of what’s going to happen in the interviews would be lost. Inevitably, you have to play up certain elements which the real person may find some argument in.”

The long days on stage and set were made easier by the help of a constant companion in the work, Langella. Reflects Sheen, “It’s been an amazing journey. Pretty much every day, nonstop for 18 months, we’ve told this story together. It’s always seemed fresh, and it’s always seemed no matter what environment we’re in-theater or in front of the camera-there’s a spark that’s there. We both respond to it and to each other. That chemistry is a rare thing.”

Working Title producer Eric Fellner particularly liked the manner in which Sheen dealt with Frost’s fluctuating insecurity and ego. He provides, “Here is this chat show host trying to nudge his way in for the interview of the century. You must admit that the hubris Frost showed was astounding. Michael gives that so effortlessly with his portrayal. At times, you watch him wracked with insecurity; other moments he’s brimming with self-confidence. Few performers can run that gamut the way this man can. From the minute I saw him at the Donmar, I believed another performer wouldn’t do Frost justice on screen.”

To portray the research team David Frost secured to prepare him for his four-part interviews with Richard Nixon, Howard and the producers cast Matthew Macfadyen, Oliver Platt and Sam Rockwell.

Macfadyen was tasked to play John Birt, the founding editor of London Weekend Television’s Weekend World and director general of the BBC. A powerful figure in British television for more than three decades, he would go on to become special advisor to Prime Minister Tony Blair from 2001 to 2005. Birt produced the Frost/Nixon interviews and organized the team that prepared the program’s host for battle.

“John Birt was a producer at the time for LWT,” says Macfadyen, who met the real Birt for lunch prior to filming, as well as at the end of the shoot when Birt visited the Los Angeles set. “He’d worked with David Frost before, very happily and successfully, and Frost sort of poached him from this company for whom he’d just gone to work. Birt was actually my age, 32, at the time of the interviews, but he was already an incredibly successful producer. I think Birt had doubts about Frost’s ability to pull off these interviews.”

Oliver Platt was brought on board to play seasoned journalist Bob Zelnick. A former bureau chief at National Public Radio, Zelnick was placed in charge of researching Nixon’s domestic and foreign policy for the Frost team. A virtual encyclopedia of Nixon knowledge, Zelnick played Nixon in the team’s rehearsals for the interviews.

“How can it be more intriguing than when Ron Howard calls to send you a Peter Morgan script?” asks Oliver Platt. “That piques your interest. You know you’re going to be involved in a quality film and surrounded by great people-the two big boxes you always wanna check before you sign on for a project. Add in actors like Frank, Michael, Kevin, Matthew, Sam…you know you’re onto something special.”

What impressed the performer most was his director’s preparation. “He has already drilled down through so many layers of the material that it just makes you better. He gets you involved at every level; he sent me a big box of clippings, books, DVDs of research that helped me flesh out the historical context of the story.”

For the role of prolific nonfiction writer James Reston, Jr., the author of 13 books, including “The Conviction of Richard Nixon: The Untold Story of the Frost/Nixon Interviews” (which recounts the author’s time spent as the prime Watergate researcher on the Frost interview team), Howard would turn to Sam Rockwell.

Like Platt, Rockwell knew there would be much preparation to play the type of academic who would eventually become assistant to U.S. Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall during the Lyndon B. Johnson administration. Volumes of research later, the performer offers, “I went to D.C. twice to meet with Jim Reston and interviewed him before we started filming. He’s still very passionate when he talks about Nixon and the time in which this story takes place. It’s a really juicy supporting role.”

The Frost/Nixon producers and director spent ample time constructing the opposing team who would assist Nixon in his preparation. That core team would consist of American film staple Kevin Bacon and British character actor Toby Jones.

Kevin Bacon would portray retired military officer (and Nixon’s chief of staff after the president left office) Lt. Col. Jack Brennan. Nixon’s negotiator in setting up the terms and ground rules for the interviews, Brennan was a bulldog. “Nixon was fascinated with the Marine Corps and, when he was in the White House, he wanted a Marine around him,” says Bacon of his character. “When Nixon resigned and retired to San Clemente, he asked Jack to come be his Chief of Staff. So Brennan became his right-hand man.”

For the actor, this film would represent another collaboration with director Howard. “This is my second Ron Howard film, and it’s been a lot of years since we did Apollo 13. It was a great experience for all of us, and I was really enthusiastic to come back and work with him again.” Bacon laughs, “He joins a very short list of directors who’ve actually hired me twice.”

Irving “Swifty” Lazar was the legendary agent who represented Nixon in extracting a record fee for his interviews with Frost. While he handled the biggest movie stars-including Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Cary Grant and Gregory Peck-he also represented some of the greatest names in that era’s literature-including Hemmingway, Capote, Nabokov, Odets, Saroyan and Tennessee Williams-and music icons from Cole Porter and Ira Gershwin to Madonna. Toby Jones found the role quite interesting.

“Playing a character like Irving Lazar…I’ve met lots of people who knew him, so it was slightly intimidating,” he says. “There’s very little information about him available other than one ghosted autobiography. My impression is of a man very driven. He started off in a poor Russian-Jewish family in Brooklyn and basically fought his way up to become the top literary agent in the business.”

British actress Rebecca Hall was cast as jetsetting Caroline Cushing, one of the few women who might tame notorious lothario David Frost. Ex-wife of wealthy socialite Howard Cushing, she met Frost shortly before he met with Nixon to propose the interview series; Cushing remained his girlfriend for several years thereafter. A former secretary to columnist Liz Smith, she later became successful Hollywood editor Caroline Graham.

With an ex-boyfriend in Los Angeles and an ex-husband in Monte Carlo, Cushing was just the sort to tell Frost exactly what she thought. Upon their first meeting, she recounts for Frost that she heard a journalist refer to him as “someone from humble origins who could reach the greatest heights without possessing any discernible quality beyond ambition.”

Of her thoughts in preparing for the role, Hall offers: “It was important to me to know as much about Caroline as I could-to meet and talk with her. But there also comes a point where you realize that Peter Morgan’s written fiction, and I have to serve the story as best as possible. I didn’t want to get too carried away with the reality of this person and think: That’s not actually accurate, and I need to do this. If we’re going be true about this, then I need to do that.’ You end up losing sight of the story. What was important was figuring out where she fits in in how to tell the story best.”

Rounding out the rest of Nixon’s team were Andy Milder as Frank Gannon, a close friend of Nixon’s and an historian who served as special assistant to the president during his White House years and helped him prepare for the Frost interviews. He wrote and researched “RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon” in 1978 and, five years later, conducted his own taped interviews of the president. Though never broadcast, these are considered Nixon’s most candid moments on tape.

Kate Jennings Grant plays Diane Sawyer, a former press assistant to the president during his terms in office. The future broadcast star served as one of Nixon’s researchers for the Frost interviews. Gabriel Jarret plays Ken Khachigian, chief researcher for the Nixon interview team. Khachigian previously served as deputy special assistant and chief speechwriter for Nixon, and later as the chief speechwriter for Ronald Reagan during his presidency.

Jim Meskimen was cast as Raymond Price, a former speechwriter for the Nixon White House and part of the Nixon interview team. Finally, the long-suffering Pat Nixon is portrayed by actress Patty McCormack (who will always be remembered for her role as the sociopathic little girl Rhoda in The Bad Seed).

It was important for the filmmakers that the exact tone of period authenticity was set from the first day of principal photography. The historical characters in the play were mostly referenced; in the movie, they were embodied. Whoever was there during the events of the Frost/Nixon tapings was portrayed either by an actor or, in some cases, by the actual individuals who were there.

Patrick Terrall, the original host of the famed Ma Maison, played himself in the replica of the restaurant he once ruled over during the time it was the hottest place in Los Angeles to see and be seen. Terrall knew them all in the heyday and David Frost was a much talked-about guest in the time leading up to the Nixon interviews.

The scene at Ma Maison features two actors playing singer Neil Diamond and composer Sammy Kahn, in a duet of a satirical song addressing the upcoming Frost / Nixon face-off. While it may seem like a fictional device, such a performance, writer Peter Morgan assures, did occur and the song “Frost and Nixon”-to the tune of “Love and Marriage”-really was composed for the occasion in 1977…not for the film 30 years later.

Lt. Colonel Gene Boyer played the helicopter pilot who ferried President Nixon away after his farewell speech. He played the role in real life as well, after the President’s resignation on August 9, 1974.

The son of another participant in the events of the day played his father in the film: GREGORY ALPERT, who was also the movie’s real-life location manager, portrayed a cinematographer who was present at Nixon’s Oval Office resignation. His father, Manny Alpert, was a cinematographer who shot for Hearst Metrotone News and covered Nixon on many occasions-though not on the actual day of the resignation.

Fiming the World of Frost / Nixon

The difficulties in translating a work from stage to screen were multiplied when outlining a story set in the past. However, the benefit of a period story permitted the director, cinematographer and designers to infuse a reality that doesn’t exist on stage. By opening up locations, Howard and the production team made Morgan’s stageplay cross continents.

For Howard, opening up the film from the play meant “bringing it to life on the streets.” He adds, “One of the things we’ve tried to do in recreating the period is to be as authentic as we could possibly be. Michael Corenblith [production designer] and Daniel Orlandi [costume designer] have been very selective in drawing on the elements of this era without making a parody of it. In fact, we’ve had to dial down a little from what we call `’70s cheese.’ If we went as far stylistically as many of the research photos indicated, it’d be pretty satirical.”

Design and Camerawork

The art department had to work on both a large and small scale to create what the stageplay merely needed to suggest. In the play, the interviews between Frost and Nixon took place on a nearly bare stage, with two chairs and a couple of television cameras. Close-ups of the two men were projected on a large screen. However, what made believable theater would not make credible film.

“Since we were inevitably going to be compared to the real (televised) Frost/Nixon interviews, we took great pains to make anything that had been seen by an audience in 1977 as perfect as we knew how, down to the slightest detail,” says production designer Corenblith. “The tiniest brick, the tiniest piece of set dressing, the shape of a leaf on the houseplants on the table-we paid attention to everything that was in the interview corner of that room. At the same time, I took liberties with other aspects of the house to give it a certain character when we did reverses.”

Following the footsteps of these two icons of the era was a trick of visual artistry and of retracing history. “While there’ll be viewers who were born in 1977, there are many others who were working professionals in 1977 and all range of ages in between,” explains Corenblith. “There’s a strong sense of period memory to which we have to try to remain faithful. We’re also dealing with a documented event we felt we had an obligation to present accurately. On the other hand, the ’70s have been replicated so often we had to be careful about not falling into cliché. We wanted to make it a character without it becoming caricature.

“We didn’t want to undercut the real emotions and the real drama of what was going on by having audiences distracted by all the garnish of lapels and sideburns and paisley. So, it was a question of how to craft something that was true to the period but not an exaggeration of the period, which was a tremendously difficult task at the end of the day.”

Costuming was also a challenge. Dressing 100 extras in haute couture from the period was a task that costume designer Daniel Orlandi relished. “Ma Maison in 1977 was the hottest restaurant in town, where all the stars went,” he explains. “It was really fun putting together this highly romantic time and place. We dressed all kinds of people from old Hollywood elite to the up-and-comers… to a couple of high-class hookers. And David Frost, of course, fits right into this with his beautiful tuxedo and Caroline Cushing on his arm in a matte jersey dress inspired by Halston.”

As for the camerawork, cinematographer Sal Totino kept his equipment in constant motion for most of the scenes, providing a documentary feeling to much of what transpires. He also brought details into play that provided period authenticity. “You just try to find moments that are intense,” Totino explains. “Little details that help build the drama in the scene-we might stay tight on raindrops using the reflection on cars. I tried to approach this film with longer lenses that just made it feel a little bit more intimate.”

Locations

Locations were also used to their best advantage to provide verisimilitude with which producers of the stageplay didn’t have to concern themselves. In the case of one particular location, the filmmakers got more than just a realistic backdrop.

“We visited Casa Pacifica, the Western White House, at the beginning of our research, but we never imagined it would be practical for us to film here,” recalls Howard. “But it’s so unique, particularly in the courtyard area and the entrance, that we just couldn’t find anything that would replicate it. I felt like I would regret not making every effort to be able to film here. Remarkably, after negotiating with the current owners, we were given permission to shoot some key sequences where some of the real events actually took place.

Filming moved off stages and backlots and into international territory when Riverside, California’s Ontario Airport was converted into London’s Heathrow Airport. Later, the southern California coastal city of Marina del Rey, California, stood in for Sydney Harbor. The challenge, as usual, was adapting not only to the venue but the period.

“We started amassing images from Heathrow, and it began to shape my idea of the film as a whole,” says Corenblith. “Ron always loves technology in transition. So I had an idea of a Heathrow terminal and concourse that blended the duty-free area and the crowds of international travelers into a sort-of image-heavy representation of the world in which Frost traveled.”

“Ron remembered going to Heathrow in 1977,” continues Orlandi. “He wanted to show a really international airport with all kinds of people. So we outfitted backpackers, a rock band, Muslim women and men, Russian and Japanese businessmen. It was loads of fun for us giving all these extras a different character.”

As the interviews were being negotiated in ’77, the selection of the subject of intense negotiations between the camps was required. Neither the Western White House nor a conventional television studio was deemed appropriate. Not far from where Nixon lived, a loyal Republican couple owned a house, which they arranged to rent to Frost’s production team. Thirty years after the fact, the original house no longer fit the part. Fortunately, a house was found in the Conejo Valley’s Westlake Village that matched the period, and the interiors were constructed on stages.

That actual couple, Harold and Martha Lea Smith, were hosted to a stroll down memory lane when they visited the sound stage in Los Angeles, witnessing the miracle of production design that made the film’s make-believe home into a virtual replica of their own. “It’s surreal,” commented Harold Smith. “It looks just the same.”

The production moved from recreating history to reliving it as filming began at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. The Beverly Hilton was Frost’s hotel of choice when he visited Los Angeles in the ’70s, and the basic architecture has remained the same today. The production ended up shooting in suite number 817, Frost’s former penthouse away from home. Nixon’s foray into the lecture circuit was also filmed in one of the banquet rooms.

“I was trying in some small way to bring a little of the old Hollywood glamour to the Hilton suite, and that was where we took the greatest liberties and license,” says Corenblith. “We had a number of great publicity photos of the Beverly Hilton when it opened in the late 1950s. So, a lot of what we were doing was taking the best of those mid-century modern ideas and kind of bringing them back.”

Continuing production in Los Angeles, Sunset Boulevard-at the corner of Vine Street-was closed for filming when The Slipper and the Rose: The Story of Cinderella premiered for the second time at the Cinerama Dome. (The 1977 film on which Frost served as executive producer was successful enough to garner two Oscar nominations for its music). For this scene, the art department had little to do other than put up the appropriate signage.

“This environment was so untouched for what we needed to play our scene, that we just moved in and shot,” says Corenblith. “The Slipper and the Rose premiere at the Cinerama Dome was like walking into a time warp, with the architecture unchanged. We had access to the graphics and all the documentary footage of Frost’s arrival, and we were able to completely replicate the event.”

The location work reached its greatest heights of recreated glory as the production moved to La Casa Pacifica-Nixon’s Western White House in San Clemente, California. Two hours from Los Angeles, the seaside retreat was built in 1927 and sold to the President in 1969, the year he took office. It was even more of a sprawling, private oasis when Nixon was living there then it is now, with subsequent owners having sold off the nine hole golf course and other undeveloped acreage to build houses.

It would have seemed the perfect place to hold the Frost interviews-and it was everyone’s first choice. But in equipment tests, it was discovered that the adjacent Coast Guard station-which handled all Nixon’s security-was using electronic surveillance that interfered with the cameras and recording gear needed for the interview.

The grounds were a spectacular place to shoot footage of the president in his element, however, and Frost / Nixon was the only film company ever to get permission to shoot in the magnificent gardens and patios surrounding the house.

“It was chilling for me to wander around these historic grounds,” Ron Howard offers. “It was an odd sensation walking around knowing that Nixon, Brezhnev, Kissinger-so many significant people from that era-had decided the course of history here. I definitely think it brought something to our actors’ performances to be working here.”

After two days at La Casa Pacifica, the Frost/Nixon production moved to another landmark, the Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, the site of the modestly built house in which the president was born and spent the early years of his childhood. The parking lot was the setting for the helicopter takeoff after Nixon’s farewell. Inside, the library’s exact replica of the East Room in the White House was a venue where the movie’s art department had little to add.

Truly, the first half of the filming traveled the globe without leaving Southern California. In addition to Ontario airport as Heathrow, the streets of London were duplicated on the backlot at Universal Studios, while David Frost’s Australian show was re-created on the Henson stages on La Brea Avenue in Hollywood.

Additionally, Nixon’s Office and Frost’s Hilton penthouse were constructed on sound stages in Los Angeles, where the production retreated to complete the last half of filming. Production wrapped on October 17, 2007, after only 38 days of a scheduled 40.

****

With production finished, the screenwriter who started the story years ago reflects on the process and why audiences will be interested in the end result. Notes Morgan, “I take the responsibility of entertaining quite seriously. I hope the surprise that people feel, like they did when they came to the play, is that adult, more sophisticated entertainment can be really fun, too. You can think and have fun.”

Of another chapter being written in the tale he and President Richard Nixon began 31 years earlier, Sir David Frost concludes it is most gratifying to see the story come to film: “That’s a great honor. Particularly because Ron realized it was a responsibility going into it. If Nixon had come out just smelling of roses, it would have been an embarrassment. The fact that it has become history is exciting and humbling.”

Production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

Frost / Nixon

Starring: Frank Langella, Michael Sheen, Kevin Bacon, Sam Rockwell, Toby Jones, Matthew Macfadyen, Oliver Platt, Kate Jennings Grant

Directed by: Ron Howard

Screenplay by: Peter Morgan

Release Date: December 5, 2008

MPAA Rating: R for some language.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $18,622,031 (70.1%)

Foreign: $7,925,639 (29.9%)

Total: $26,547,670 (Worldwide)