Tagline: The end is high.

Mankind now has an expiration date. The year is 2008, but that number matters little, as a pandemic threatens to wipe out the whole of the human race. For many in the United Kingdom—the epicenter of the outbreak—the end is nigh, so why bother to keep count?

Within days of detection of the Reaper virus—replete with open skin sores, uncontrollable bleeding and, ultimately, fatal liquefaction of internal organs— millions are infected in Scotland, the killer disease’s home turf. Government has no choice but to declare the country a “hot zone” and quarantine the populace in hopes of containing the Reaper’s spread.

With military blockades on every highway, bridge and railway, all traffic in or out is halted, and a 21st-century version of Hadrian’s Wall is erected around Scotland’s border. Sealed off from the rest of the world, what was once Scotland is now a forgotten No Man’s Land, with the Reaper given free reign to annihilate the population sealed inside.

A quarter of a century later, with a new outbreak of the Reaper resurfacing in an overcrowded London, it becomes apparent that the government’s best laid plans have gone completely, bloody awry. Department of Domestic Security (DDS) Chief Bill Nelson (Bob Hoskins) is summoned to meet with the prime minister (Alexader Siddig) and the true power behind his office, Michael Canaris (David O’Hara), who reveal satellite photos of Reaper survivors in the hot zone. And survivors must mean there’s a cure…

Nelson quickly assembles a crack team of specialists to venture into the forsaken land and retrieve the counteragent to the virus, once the pet project of the now presumably dead Dr. Kane (Malcolm McDowell). For the tough and efficient commanding officer, Major Eden Sinclair (Rhona Mitra), the assignment represents a disquieting homecoming. Twenty-five years earlier, in the final moments of containment, she had been shoved into one of the last evacuating military choppers and flown to safety…forced to leave her mother behind.

Once on the other side of the immediately resecured border, the squadron— which also includes Sergeant Norton (Adrian Lester)—is on its own, venturing into a ghoulish terrain of corpse-strewn, forlorn cities. All too soon, however, the crew meets up with a pack of feral survivors, and finds itself unwittingly standing in for the callous government that turned its back years before. Caught between two bloodthirsty factions of the Reaper’s legacy, Sinclair and her decimated squad fight to remain alive while racing to retrieve the cure…before the reborn virus ushers in the dawning of a new dark age.

About The Production

DOOMSDAY sees the acclaimed, on-the-rise director working on his biggest canvas to date, following the success of his two well-received films, Dog Soldiers and The Descent. For Neil Marshall—who, in his native U.K., is referred to as one of the “Splat Pack”—this meant splashing the screen with a combination of nonstop action and in-your-face thrills, set in a near futuristic and fully nightmarish landscape. But going against current action-thriller custom, with its heavy reliance on flashy effects born out of CGI, he was intent on creating the type of film he grew up on, one rarely seen in the multiplexes nowadays.

He opens, “One of the things I was adamant about doing with DOOMSDAY was going back to a kind of gritty stunt/action movie that doesn’t get made anymore: real people, in a real world, doing really dangerous stuff! No green screen, no wires, just crazy ‘stunties’ standing on, jumping into and hanging out of cars traveling at 80 mph and smashing into each other.

“In that way, DOOMSDAY is my vision of the future,” continues Marshall. “A deadly virus attacks the U.K. and the government is forced to build a wall to quarantine the whole of Scotland in order to ensure the survival of the rest of the nation. The story picks up 25 years in the future, when an elite team is sent in, over the wall, to try to find a cure for the Reaper virus.”

For producer Benedict Carver—president of Crystal Sky Pictures, which is headed by fellow producer Steven Paul—Marshall’s evolution from helming a small budget to a somewhat bigger budget was natural and expected. “Dog Soldiers was quite a good, economical film,” Carver offers. “So was The Descent, and Neil wrote and directed both. If you’re a good director, you can direct a film at any budget. And, to my mind, he showed real ability with both of those films that could translate to DOOMSDAY.”

While this film may glance over its shoulder at some of the outstanding genre films of the 1970s and early ’80s, it is definitely a current-day creation of the inventive storyteller who conjured Scottish soldiers being picked off by werewolves and strong women trapped in caves with bloodthirsty predators.

Producer Paul comments: “Neil’s latest is inspired by the postapocalyptic films of the past, like Escape From New York, The Warriors, The Omega Man and Mad Max. Those are the films that have inspired Neil and us to make this movie. We wanted to do something reminiscent of the films of John Carpenter and George Miller, and all those great genre directors of the ’70s. Although we’re sort of paying homage to those kinds of films, Neil completely brings his own original mix to DOOMSDAY.”

Originally, the idea for the film came to the director as he imagined a scenario in which an ultramodern action warrior is confronted by a knight in armor…in a postapocalyptic landscape. Observes Marshall, “I think it’s a genre that hasn’t been tackled for awhile, and it harkens back to the films that I love.”

All acknowledged that creating such a vision in this postmodern way would present its own set of challenges. Per Carver: “We knew this was going to be a very difficult project to put together, basically because it’s a big action film that we were going to make for a modest budget. And Neil wanted to do all of the action in a more physical way, as opposed to relying on a lot of visual effects. So, we had to find somewhere where we could put everything together and shoot it ‘for real,’ as opposed to doing it on a computer.”

And shooting it for real necessitated finding a cast eager to perform it for real…complete with sucker punches, oozing sores, severed heads, sword fights, car chases, cannibal feasts, mob scenes and more.

When Marshall had written the treatment for the film five years earlier, it had centered on the character of Major Eden Sinclair.

Describing her, he says: “Sinclair is a hard-nosed soldier, a cold-blooded killer in the near future, who, somewhere along the road, has lost her soul. She is a product of the system in which she grew up, but she has a different history and is connected to the story on a very emotional level. Her mission—to find the cure for the lethal virus—is a journey of redemption and soul-searching. She has to reconnect with her humanity. It’s her homecoming, literally, and she has to find what she lost as a child. Because of the virus, and its disastrous effect on her country, her life has turned out very differently from the plan. She has had to become very independent, because she had no one to look after her. She learned to fight on the streets, and hold her own amongst the guys.”

In his previous films, Marshall has worked with relatively unknown actors, having once declared that he planned, like director John Ford, to work with the same ensemble cast on all his movies. He says, “Ideally, I want to work with a kind of theatrical ensemble on every film, but each time, trying something new, swapping them around and giving them new roles, so that they can have fun with something different. At the same time, I want to add new actors to the mix to keep it fresh.”

The writer / director also notes that, while he keeps his ensemble in mind while penning the screenplay, he does not necessarily write the parts with specific actors already assigned. He remains open to the process…so open, in fact, that to fill his leading role of Sinclair, the filmmaker utilized open auditions.

Into those calls walked Rhona Mitra, an English actress now based in Los Angeles, who has received much attention thanks to her performances in such television hits as The Practice, Boston Legal and Nip/Tuck and the films Shooter and The Number 23.

Director Marshall: “Her audition was great, and when we met her later in London, we realized that we had found Sinclair. Her reading of the character was gritty and tough, but she understood the emotional journey and Sinclair’s connection to her past.”

Mitra immediately recognized something in the character of Sinclair. Mitra observes, “She is disillusioned with the state of her country, and when she is offered this mission to return to where she came from, to try and find the cure for the virus, she grasps the opportunity to go back and find out what really happened. Her journey is incredibly varied, traveling through these diverse visions of history and fashion and culture and madness that is this world Neil has created.”

Mitra continues, “Sinclair doesn’t have a chip on her shoulder, she just sees the world for what it is. She’s not a bimbo and she’s not a ball-breaker, but she is very no-nonsense. I play her as a streetwise London girl, which is what I am. She has to be physically fit, but I also wanted to ensure that I didn’t look like I’d spent 24- hours-a-day in the gym.”

The actress was impressed with Marshall, beginning with their first meeting to discuss the role. She realized that his conviction was palpable, and that he was going the film the script he had written with total support from the studio. The two also discussed the repeated mishandling of the role of the female action hero onscreen, and both found a couple of stellar exceptions to the rule: Linda Hamilton in The Terminator and Sigourney Weaver in the Alien series. (While Mitra found inspiration in those women during filming, she was also influenced by two men: “I definitely occasionally felt Mel Gibson or Harrison Ford sitting on my shoulder in some scenes!”)

In addition to the obvious action-thriller-adventure elements, Mitra found resonance in the themes of ecological fragility and political duplicity that affect our world today. She reflects, “Unfortunately, we’re facing those same things now.” And while Mitra would be joined by actors from Marshall’s previous films— including Sean Pertwee, Craig Conway, Myanna Buring and Darren Morfitt—the director was anxious to work with other actors of the stature and experience of Bob Hoskins and Malcolm McDowell. “Bob and Malcolm both bring vast experience,” he commends, “and it has been a real pleasure to work with them. They know what they are doing, and they get on with the job.”

According to the veteran McDowell, it was the genre of DOOMSDAY—or the amalgam of genres—along with Marshall, that figured heavily in his signing on. He muses, “I’m not sure what genre it is, actually. What’s nice about it is that it’s not a horror film, it’s not a sci-fi kind of film, but it’s a mixture of a lot…say, an adventure film with sort of sci-fi and horror elements. It’s hard to pigeonhole it. And that’s its strength, not its weakness. It’s a tremendous script, and Neil has a tremendous track record.”

Too, it didn’t hurt that the role of Kane was a plum one. McDowell continues, “Kane’s this large character—he’s the leader of the surviving parts of the human race. They’ve survived by natural selection, and he’s a man who’s isolated in a pocket in his own little kingdom. So, basically, he’s the king of his own little world, and that’s fun to play. In some ways, he’s King Lear, really.”

For Bob Hoskins, the director and his signature style were more than enough reason to accept the part of DDS Chief Bill Nelson, the commanding officer and stand-in father figure for Eden Sinclair. Per Hoskins: “Neil, he’s fantastic, an English Tarantino. He’s very quiet, and he knows what he’s doing. I mean, there are scenes with blood and guts, shooting, stunts, prosthetics and the rest of it. He knows exactly what he wants, and you do the exact amount of takes that you need.”

The RADA-trained Adrian Lester has proven himself to be quite versatile in his choice of roles, from classical theater and West End musicals to major film and television roles as a con man, campaign manager and archaeologist. His past movies include Primary Colors and The Day After Tomorrow. It doesn’t hurt that he also has a secret talent.

Lester says, “I knew this project was going to be physically demanding, and I was really looked forward to it. The weapons training we received was very detailed and effective, and I finally got a chance to use some of my martial arts training. [Lester has a black belt in Tae Kwon Do.] Neil wanted the action to look real and gritty, and after eight or nine takes of some of the sequences, I would need to soak in a hot bath! I would have liked to do more of the stunts, but if I had of survived them, I’m sure my wife would have killed me.”

Although Alexander Siddig is the nephew of Malcolm McDowell, nepotism had nothing to do with his being cast as the prime minister, a man desperately trying to helm a nation threatening to degenerate into an epidemic-ravaged bedlam. (The family relationship was not discovered until after both actors had their parts.) Siddig recalls his first unremarkable (and slightly embarrassing) encounter with his new director: “I hadn’t met Neil before I started filming, as I was in some other country when he was getting the cast together, and I was lucky enough to be offered the part. So I arrived on set on a Friday and got off the plane a little groggy. This guy came up to me, very pleasant, sweet, polite, quiet. I thought he was going to ask if I needed anything, and I said something like, ‘No thanks, I don’t really want a coffee or a chair or anything.’ And he said, ‘Um, but I’m the director.’ All I could say was, ‘Oh, well, hi, it’s nice to meet you!’”

For the role of the scheming Canaris, filmmakers selected David O’Hara, an actor who easily segues between parts on both sides of the law—so portraying a public figure with ulterior motives would fit nicely into his resume. O’Hara knew that Canaris was that most classic of characters, the real power behind the ruler. Of course, he didn’t dwell on whether the Iago was a “good” or “bad” guy. He was keen to not classify the character as either and focused on Canaris’ motives, allowing the audience to decide if he is the villain or not.

Envisioning the Future

Comparing the scale of DOOMSDAY with his previous feature films, Marshall explains, “My last two films were both essentially a small group of people in a very contained environment. The biggest crowd scene was perhaps 20 extras, whereas on DOOMSDAY, we were going to need 50 extras on the first day and almost 1,000 in later scenes. We were going to have to shoot in a range of locations—streets, forests, mountains, castles and inside ships. I wanted to work on a huge scale, what I’ve done before. It seemed daunting at the outset, but I knew it was going to be a huge adventure.”

To realize this ambitious adventure, Marshall chose to work with many of those with whom he collaborated on previous projects, including director of photography Sam McCurdy, production designer Simon Bowles and prosthetics makeup designer Paul Hyett. The filmmaker explains: “I like working with my mates, and they bring something fresh to each film that we do together. We have good camaraderie on set, which spreads to the rest of the cast and crew. It’s been a growing-up process for all of us, a challenge. Simon has built wonderful sets, Sam makes everything look fantastic and Paul never lets me down when I need more gore.”

Together, the creative team has synced on its “Marshall Style”: “If I have any kind of visual style, it’s that I like to do as much as possible in-camera; it’s something I picked up from Ridley Scott,” the director notes. “Although we were going to use some visual effects on DOOMSDAY, I don’t ever want to rely on them. I like things to look raw. If someone is going to be hit by an axe, I don’t shy away from the aftermath. If there is a fall, someone will get hurt, not stand up and walk away. I want it to look as realistic and brutal as it should. I think practical effects stand the test of time, where visual effects are being refined and can end up looking really dated.”

Months before principal photography began, filmmakers ordered up concept paintings, to discuss and modify how the scenes might look. The director utilized his customary storyboards on every scene, particularly the action sequences. However, once shooting began, these paintings and storyboards were never referenced, as Marshall wanted to remain open to new ways of capturing a scene on film, as well as allow the actors to move within the locations as motivated by character.

(Interestingly, after the film had wrapped, Marshall reviewed the early concept art and found that his departments had more than delivered, as those pre-shoot looks had been either matched or topped by his creative crew.)

DOOMSDAY’s shooting would take place primarily in South Africa, where the varied and plentiful location possibilities—both structural and landscape—would stretch production dollars that would ordinarily be spent on expensive set construction. Not to mention the weather…as principal photography was slated for a January start date, the high summer weather would prove a boon to the large, outdoor scenes conjured in Marshall’s script. Following the 66-day shoot there, production pulled up stakes and hightailed it to the U.K., for two weeks of filming in Scotland and the lensing of one very special location in London (what would a film set in the U.K. be without an iconic shot of the London Bridge?).

In South Africa, production was headquartered in Cape Town, which proved to be governed by a cooperative bunch. Marshall offers, “Shooting DOOMSDAY in Cape Town was an adventure in an amazing landscape. The crew was awesome. The locations were spectacular. The weather was incredible. We exploded countless pyros in the center of Cape Town in the middle of the night. We closed down the city center on a Saturday afternoon to stage a frantic foot/bus/motorbike chase. We took over a major theme park, dressed it as the villains’ lair and filled it with a thousand screaming extras—waving baseball bats, hanging from the rafters and generally baying for blood. They had a lot of fun that night, and so did we.”

On location in South Africa, the production was also permitted to use Cape Town City Hall as the exterior of St. Andrew’s Hospital Glasgow, where Sinclair’s team arrives in its armored vehicles to explore. The hospital they find is long abandoned and covered in weeds, with broken windows and shells of cars clogging the roads outside. Working by night, the building was dressed with foliage and burned-out automobiles. The onlookers may have been surprised to see the same balcony where Nelson Mandela addressed the crowd on his release from prison transformed into deserted wasteland. (Strangely, no one seemed to notice when production began to set off Molotov cocktails at 4 a.m.)

According to Marshall, the cycling in of new filmmaking talent is something that benefits both director and cast: “There was a great spirit on set, and I think that feeds into the energy of the actors, too. I don’t believe in the auteur theory, as I bring people in to collaborate with them. I give them freedom because I want their input. It’s pointless employing people if you continually reject their ideas, and that applies to actors and crews. My job is not to deny people their say, but to filter that input and decide whether it works for the film or it doesn’t.”

This synergy resulted in a realized vision that impressed even the film’s producer. Says Benedict Carver, “The production design has been fantastic. We’ve been a location-driven film. We haven’t built that many sets, but the sets that we have built have been really fantastic—mainly our command center, which we built in South Africa. We’ve had to dress a lot of sets, and I think we’ve really done a great job there—distressing things, making things look rundown, transforming locations— so that they fit in with the look of the film.”

Production designer Simon Bowles elaborates on the theories that lay behind the world of DOOMSDAY, basically incorporating five distinctly different time zones into one. He notes, “We start in present-day Scotland, where the virus has taken hold and the wall is being closed to contain it. Then, we jump forward to London 25 years later, which is cut off from a world which fears the virus will spread. London has two societies: the very poor police state, and the futuristic warriors who control it. We revisit Scotland and see the Marauders’ world, a renegade outpost where they’ve used everything abandoned and broken-down to make new things for themselves, particularly weapons and cars. And then we travel to Kane’s castle, where the survivors have retreated into a modern version of medieval life—they look as if they’ve raided museums. All these scenes have different looks and different people…the huge challenge is when those different worlds collide and mingle.”

One of the film’s biggest set pieces is the surreal rally orchestrated by the leader of the pissed-off punk survivors, Sol. Marshall enthuses, “The scene I expected to be most challenging was the action at Sol’s headquarters, with hundreds of Marauders, fire eaters, trapeze artists, bikers and Craig Conway as Sol, living out the ultimate rock-star dream, stoking the crowd into a frenzy. It ends up with Sean Pertwee [as Talbot] being barbecued live onstage and then devoured by the crowd. In fact, it was great fun, and one of the easiest scenes to shoot, once we had worked out the logistics.”

Marshall continues, describing the circus from hell: “Onstage, we had a floorshow of pole dancers and a group of fat guys dressed in kilts doing the can-can. All this was going on behind Sol, who is egging on 800 of his followers to the big finale. Craig Conway loved playing the rock god, leading his Marauders, but I think Sean Pertwee was a bit taken aback by the scale of the scene when he was wheeled in as the human sacrifice. Simon Bowles had created a vehicle called the Griller Killer, with Sean suspended on a crane arm and lowered down over flames. As he is being roasted alive, the crowd lines up, plates in hand, ready for the dole out of his flesh. In the end, Sean was chuffed, because he definitely has the most spectacular death scene. No one has seen anything like this on film before!”

What was dreaded ended up delighting all who participated—if a flambéed human for dinner can delight anyone. Designer Bowles filled the amazing set with wrecked cars, skulls, metal sculptures, graffiti and old furniture. The hundreds of extras all looked the part of a mad crowd that grew up behind the wall (think of the boys in Lord of the Flies two decades later), each with individualized makeup, hair and wardrobe. The result is an insane mix of Moulin Rouge! and The Wicker Man.

Another scene high on the list of challenges was the sequence in which the wall between Scotland and England is sealed, abandoning the northern population to certain death by Reaper virus. Creating a modern version of Hadrian’s Wall, the art department built a 300-foot-long, 30-foot-high portion of wall across a country road, using an ingeniously easy assembly system Bowles found, which uses temporary metal casing into which concrete is poured and left to dry. The resulting panels, when joined, look like something the British government (25 years hence) might have on hand for emergency use…just in case it needed to block off anything virulent. The designer added corrugated iron casing to give the wall a more solid look on film.

The sequence was shot over three nights and involved hundreds of extras (as desperate civilians trying to escape from Scotland while soldiers hold them back), cars in a long roadblock at the border, army vehicles and a helicopter in which the young Eden Sinclair is lifted to safety. Says Marshall, “The extras had to cause a riot and run at the wall at the same time as our special effects were firing squibs for gunfire. It was difficult and potentially dangerous, but our stunt people did a great job choreographing the whole thing.”

As an inside joke, production included a group of Hare Krishna followers as extras, reasoning that they pop up everywhere one goes. They worked so well that the director kept them throughout the sequence, with them appearing in all of the major action scenes. At the end of their stint filming, the Krishnas presented Marshall with a Spiritual Warrior book and declared him an honorary member of their Hare Krishna group.

Just as the team may have thought that their biggest challenges lay behind them, it was time to stage DOOMSDAY’s breathless car chase, pitting a Bentley-driving Sinclair and her remaining associates against the Marauders—who were driving a variety of eccentric vehicles, including old buses, police cars and motorbikes, all fashioned out of something else. Says Marshall, “We used 10 cameras on the scene. I’d never seen 10 cameras together before. The car chase is part Bullitt, part Mad Max, but mostly Neil Marshall.”

The last three weeks of South African shooting were spent entirely on the chase. This established a record for Marshall as the longest ever spent filming a single sequence, with each day of shooting featuring at least one or two dangerous stunts or pyrotechnics. Although the production did see a few close calls, luckily no one was injured during filming.

One of designer Bowles’ favorite props was Sol’s car. He explains, “We took a beautiful classic Jaguar and covered it in human skin, badly sewn together and stretched, with faces looking out of the surface and skeletal hands holding mirrors and accessories. It illustrates how cheaply life is regarded in his world.”

Clearly, with all of this action being planned, the cast needed to be game for almost anything, particularly Mitra, whose character of Sinclair is rarely off-screen. Just as production relied on a pre-shoot prep period to ready for the filming ahead, Mitra spent three months prior to shooting inside a gym working on fight choreography, as well as in driving and stunt training, along with physical strength and endurance work. By the time Sinclair appeared in her first scene, Mitra was in peak form.

As the stunt coordinator on DOOMSDAY, Cordell McQueen—whose extensive resume also lists credits as special effects supervisor—was responsible for all of the Herculean physical acts contained in the script. For Cordell, the physical training was the easy part…exploding, flipping, destroying and any other “wow factor” from Marshall’s mind equalled the times where things could get tricky. He explains, “We had a special fitness program for Rhona, which she continued throughout the shoot. We had to be careful during filming that she didn’t tire herself out. For me, though, one of the most challenging scenes was crashing the APC [the two specially-built, armored all-terrain vehicles], because we didn’t have a test vehicle to work on. So we constructed scale models of the APC to try and figure out the right-sized ramp to flip it. It was a big chunk of steel that weighed about eightand- a-half tons, so it was going to be a feat. That stunt involved the longest thought process, and it worked out perfectly in the end.”

In May, production pulled up stakes for Glasgow, Scotland, to film highland scenes, including Mitra’s most physically challenging sequence. The gladiatorial battle against Telemon, Kane’s champion, was brought to life with South African karate champion/towering physical giant Hennie Bosmana. Described by Marshall as a David and Goliath situation, Sinclair manages to outwit the enormous fighting machine by using his own strength against him. “It’s basically an execution, or trial by combat,” the director explains, “but dragged out in an arena to entertain Kane’s people. In Medieval-land, they like a bit of gratuitous violence. It was the last scene we shot there.”

For the sequence, Mitra called upon her muses: “I think actors who do action well try to add a little bit of flavor, sometimes, because it’s a serious matter we’re dealing with. And Neil tries to put in a little bit of a ‘wink and a wiggle,’ as I call it. Harrison Ford has a good wink and a wiggle in serious moments. And, of course, Mel Gibson does. On the other side, Sigourney Weaver plays it straight as anything. So, those were my sources…you know, little angels and devils on my shoulders.”

The location for this epic battle was Blackness Castle, on the Firth of Forth on the east coast of Scotland. First built as a stronghold in the 15th century, the stern grey building juts into the water at the mouth of the river Forth. Although not far from Edinburgh, the Castle looks bleak and remote enough to stand in as Kane’s headquarters, where he and his people have retreated from the world that left them to die.

The finale of this sequence involves an explosion ripping through the structure, and Marshall recalls, “I remember our Irish FX supervisor had a very charming and cool way about him. Rather than be all gung-ho and cue the explosion with a loud ‘Green for go!’ or ‘Hit it!,’ he simply and calmly spoke to the man with his finger on the button and said, ‘Blow up the castle.’ It was the perfect way to end the shoot. We wrapped right on schedule and under budget.”

Producer Carver praises, “We were thrilled to be shooting in Scotland; we have had a great relationship and a lot of help from Scottish Screen, and also from Historic Scotland and the Glasgow Film Office. Their help basically enabled us to film there.”

It probably goes without saying that a death from the Reaper is anything but poetic. To help concoct the mother of all viruses, Marshall again looked to designer Paul Hyett, who provided prosthetic make-up for The Descent, most notably creating the look of the terrifying and slimy Crawlers. Hyett worked on all the prosthetics throughout DOOMSDAY’s shoot, viral and otherwise, which involved gallons of blood (as characters were pole-axed, beheaded and run over by tanks, and also when extremities such as limbs and heads needed removing).

The Reaper virus makeup debuted on the first day of shooting, in a presentday scene in which the alpha patient—Patient X—shows symptoms and is taken to a London hospital, alerting the authorities that the virus has reappeared in the capital. Says Hyett, “Neil’s instructions were, ‘It’s got to look as nasty as possible. We want to feel that if one of these guys coughed on you, you’d be dead!’ I explored the topical symptoms of many diseases, mainly fungal infections and venereal diseases. You can find all kinds of truly horrid skin disorders on the net these days!”

Then, Hyett executed various test looks for camera, so that Marshall could choose the one he thought appeared most unsightly on screen. After due consideration, he chose them all, charging Hyett to incorporate all of the various pustules, rashes, sores and boils into one super look for the Reaper. The team worked especially hard to make sure that no disgusting details were overlooked, including the appearance of the eyes (“One thing that is often ignored,” states Hyett). The eyes were “pulled down” so that it looks as if the infection causes the gradual loss of the eyelid, with the eye itself showing through. Contact lenses were added for a yellowing effect.

Makeup and hair designer Tahira Herold comments, “My favorite moment of the shoot was the first night that we had the Marauders out. Neil pulled me over—I expected a note to tweak something, change this or alter that, because the scene was filming in two days. But what he said was, ‘They look fantastic. Thank you so much!’ And I sort of kept my composure and then ran to my team and jumped up and down—we had this little celebration moment, because I was just so proud of what we had done. It was amazing. The Marauders, led by Sol and Viper, their whole look was such an amalgamation of tribal influences—everything from the punks of the ’70s to the really cool-cat kids today. And we had nailed it.”

Marshall was surprised when Hyett pointed out that DOOMSDAY features more blood and guts than their previous collaboration. “Paul told me the difference is that the gore in this film is more evenly spread—it’s not all in the last half-hour,” he states. “We haven’t made a horror film, but I suppose I can’t resist splashing the blood around.”

Such a rough-and-tumble shoot was bound to leave its effect on both cast and crew. After all, they had logged innumerable hours (and countless frequent flier miles) to create a bizarre and brutal look into a near future in which our existence is threatened by a horrific virus that aims to do what no human has been able to accomplish—dominate the globe.

Star Rhona Mitra came away with some cravings, plus a form of communication nonexistent to the stoic Major Eden Sinclair: “I have my nieces and nephews that I want to go and get cuddles from. I need cuddles,” she laughs. “You know, I didn’t have one break. So, it’s time for little babies and stuff. I need to go and see my dogs. And I really want to eat. I want a burger. And to go by my favorite fish and chips shop.”

And on the downside? “If somebody upsets me, my knee-jerk reaction is to punch, elbow or head butt them. I’ll have to keep that in check.”

Neil Marshall concludes with what he hopes for DOOMSDAY: “Although it’s almost like a journey through time, there is no actual time travel involved. These very different worlds exist all in the same time frame. At the end of the day, I hope that audiences get an incredible thrill ride, a journey of the imagination.”

Production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

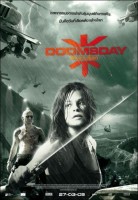

Doomsday

Starring: Rhona Mitra, Bob Hoskins, Alexander Siddig, Adrian Lester, Sean Pertwee, Darren Morfitt, Emma Cleasby, Chris Robson, MyAnna Buring

Directed by: Neil Marshall

Screenplay by: Neil Marshall

Release Date: March 14th, 2008

MPAA Rating: R for rong bloody violence, language and some sexual content / nudity.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $11,008,770 (51.0%)

Foreign: $10,592,620 (49.0%)

Total: $21,601,390 (Worldwide)