Terminal Island: The very near future. The world’s hunger for extreme sports and reality competitions has grown into reality TV bloodlust. Now, the most extreme racing competition has emerged and its contestants are murderous prisoners. Tricked-out cars, caged thugs and smoking-hot navigators combine to create a juggernaut series with bigger ratings than the Super Bowl. The rules of the Death Race are simple: Win five events, and you’re set free. Lose and you’re road kill splashed across the Internet.

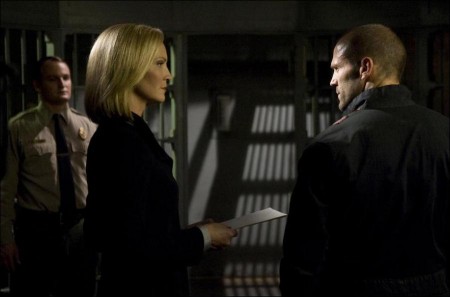

International action star Jason Statham (the Transporter series, The Bank Job) leads the action-thriller’s cast as three-time speedway champion Jensen Ames, an ex-con framed for a gruesome murder. Forced to don the mask of the mythical driver Frankenstein, a Death Race crowd favorite who seems impossible to kill, Ames is given an easy choice by Terminal Island’s ruthless Warden Hennessey: Suit up and drive or never see his little girl again.

His face hidden by a hideous mask, one convict will enter an insane three-day challenge in order to gain freedom. But to claim the prize, Ames must survive a gauntlet of the most vicious criminals-including nemesis Machine Gun Joe (Tyrese Gibson of Transformers, 2 Fast 2 Furious)-in the country’s toughest prison. Trained by his coach (Ian McShane of The Golden Compass) to drive a monster Mustang V8 Fastback outfitted with 2 mounted mini-guns, flamethrowers and napalm, an innocent man will destroy everything in his path to win the most twisted spectator sport on Earth.

Revving Up for Death Race

It is not surprising that British filmmaking partners Paul W.S. Anderson and Jeremy Bolt were fans of executive producer Roger Corman’s Death Race 2000. Considering the duo first gained notoriety for Shopping-a dark tale about joyriding youth set in the near future-it seems only natural the world created by producer Corman and director Paul Bartel in 1975 would inspire their choices.

Recalls Anderson of his memories of the original: “I was a big fan of the Corman movie. I saw it on video when I was still living in England as a teenager. It was the movie your parents didn’t want you to see, because it was just packed with senseless violence and unmotivated nudity. So, of course, I just loved it.”

At a screening for Shopping at the 7th Annual Tokyo International Film Festival, producer Bolt and Anderson first met Corman and discussed the idea of reworking Death Race 2000 for a new audience. At the time, Anderson and Bolt were about to make Event Horizon for Paramount, the studio where they first met Paula Wagner and Tom Cruise. The production partners had just launched C/W Productions and expressed interest in developing the project.

Bolt recounts: “I met with Paula at the Dorchester Hotel in London, and she thought it was a fantastic idea. They came aboard, optioned the material under their deal with Paramount and started to develop it. At that point, the idea was a movie similar in spirit to Roger’s film. In other words, it was slightly satirical.”

More than a decade would pass before the project would finally gel. Taking their cue from society’s current obsession with reality television, Anderson and the producers decided to set the film in a dystopian near future. There, they would incorporate the most extreme of reality TV and turn the drivers into prisoners fighting a gladiatorial battle.

Anderson, who by this time had written and directed successful actioners such as Resident Evil and AVP: Alien vs. Predator, took over writing duties, and the project found a home at Universal. Of the Earth he imagined, he explains, “It’s a slightly rougher world than we live in now, but still very much recognizable. The explosion in crime rates and the fact that reality television is big have led to the Death Race. It’s the ultimate in reality television: nine racers who race to the death on this sealed course. They’re the gladiators of our time, and the racetrack is their coliseum.”

While this action-thriller is quite different from Corman’s classic, one thing would not change. The fans are just as zealous in their passion for favorite drivers to massacre competitors. The more blood shed, the happier these Romans.

Locking Up Cons: Casting the Film

When casting Death Race, the filmmakers looked for performers who embodied the gritty realism of the world Anderson imagined. After meeting him, the director felt British actor Jason Statham was his Jensen Ames. “The idea was to fashion a very blue-collar hero,” offers Anderson. “That’s why I thought Jason was a perfect choice to play Jensen, a man who’s got a hard-luck story.”

Through Ames, Anderson sets up the future. In the violent, impoverished world, there is little hope, but Ames has found a reason to live. “He’s working in a crumbling, rust-belt town as a steel worker. The steelworks is closing down, and he’s just lost his job,” says Anderson. “This is a tough guy who’s been to prison before and would’ve gone back if it weren’t for the fact that he’s found this woman who loves him. They’ve had a child together, and she’s his second chance at life.”

It didn’t hurt the lifetime athlete’s chance at landing the part that in his long résumé of action films-from The Transporter series to Crank and The Bank Job-he has done a good deal of his own stunt work. Apart from the attraction of such a role and fast cars, Statham was also impressed by how intricate Anderson’s vision of the near future was. “Paul was a wealth of information about this story,” recalls Statham. “It was so detailed: pictures of the cars, the emotion of the character; he knew every beat of the story. I thought the script was emotional, fun, dark, violent and sexy.”

Statham, a self-professed “massive car geek,” especially liked the sketches of the cars Anderson showed him, particularly those of the Mustang that he’d be driving as Hennessey’s “Frankenstein.” “We’ve seen cars with nitrous oxide systems before, but I’ve never seen anything like what Paul does in this movie,” Statham says.

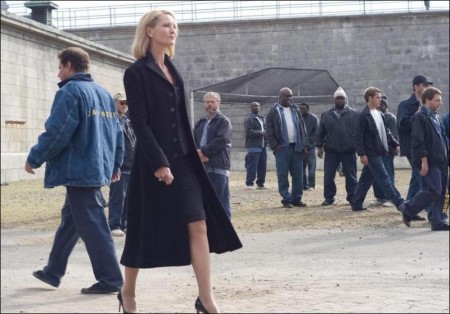

For the warden who forces Ames to become her star driver and the coach who trains him, the producers didn’t want stock character actors. They looked to dramatic performers such as Joan Allen and Ian McShane to add credibility. “You’re not used to seeing Joan Allen in a movie like this,” laughs Bolt. “It was awesome to hear her swearing like a trooper, because I associated her with roles like a female president or a headmistress.”

Tony Award-winning and three-time Academy Award nominee Allen was asked to play Warden Claire Hennessey, a well-tailored jailer who has all the power on Terminal Island. “It was a very cool script, and I was really taken with the characters,” Allen recalls. “I thought the cars were amazing and the concept was exciting. It reminded me of Road Warrior and Blade Runner in look and feel. After I met Paul and saw how he was conceiving it, I just thought, `Wow, this could be really incredibly cool.’”

The actor looked forward to taking on a character like no one she’d played before: an extremely pious sociopath. “Hennessey is an interesting study of somebody who gets wrapped up in the media and numbers and forgets human lives are at stake,” Allen continues. “My character only sees Death Race as an incredibly popular show that people really want to watch. She takes pride in that and gets kickbacks from it.”

For the role of Frankenstein’s Coach, the filmmakers turned to Ian McShane, most recently seen on Broadway in Daniel Sullivan’s revival of Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming. The actor was interested in being a part of a film he describes as “like NASCAR to the death, inside prison. Everybody tunes in to watch convicts kill themselves in their cars and blast the crap out of each other around this racetrack.”

For his part, McShane believes, “Coach is one of the good guys-an honest man who’s been in prison for so long that he’s adapted and made it his home. As the chief mechanic, he knows all the cars, but he mainly works on Frankenstein’s Mustang.”

Multiplatinum-selling musician and actor Tyrese Gibson knew playing a ruthless murderer would be a challenge. “Machine Gun Joe is evil,” says Gibson. “He’s an inmate, a leader and a killer. This role was so dark. It was really hard for me to come on set and be dark and then, between takes, get back to being my normal self: fun, laughing, cracking jokes.”

Natalie Martinez stars as the sexy and tough Case, who is shipped in from the women’s jail-as are almost all navigators. Her job, as we are led to believe, is to help Frankenstein to victory in the Death Race. But Case has got a couple of sneaky moves of her own. “She’s in jail, and the warden’s waving freedom around,” explains Martinez. “Case is very easily manipulated to do anything anybody wants.” Martinez, however, did not have to be coerced to hang tough. During production, the performer literally threw herself into her role, even hanging out of the window of the moving Monster during gunfire takes.

Cast as Frankenstein and Coach’s pit crew were Jacob Vargaz as wiseguy Gunner and Fred Koehler as the brilliant-but-shy Lists. Frankenstein’s competition is a rogues’ gallery of hardened men. They include mob man Yao Kang, aka 14K (Robin Shou); The Grimm Reaper, aka Grimm Robert Lasardo, a clinical psychopath who worships the warden; and Travis Colt (Justin Mader), a former NASCAR driver who killed several innocent people when wasted. Ames also has to contend with one of Hennessey’s favorite drivers, psycho neo-Nazi gang leader Slovo “Angel Wings” Pachenko (Max Ryan), as well as the warden’s henchman, Ulrich (Jason Clarke).

Cast and crew locked, it was time to create a holding facility that would serve as the last stop for those who’ve had a life of crime…and a racetrack from which most would never leave.

Welcome to Hell: Designing the Near Future

While Anderson, the producers and production designer Paul Denham Austerberry wanted to create a decaying world that reached slightly into the future, there were aspects that came into focus only when they settled on location. The solution was found in Montreal, which offered a prime space for Terminal Island in the now-defunct Alstom train yards in the Pointe St. Charles district. The yards served as primary exterior shooting locations and offered a grimy, industrial warehouse in which to house production. Alstom also had enough room to build sets for the island’s interiors. With much of the infrastructure gone, the crew had to rewire the space to make it usable.

Offers Anderson: “The locations look almost like they’ve been built for the movie, but they were found; they give Death Race great production value. The movie wasn’t written for these locations, so I had to go back and rewrite the script to tailor them to these fantastic places we found.”

The team envisioned the death-trap racetrack to run between the disused warehouses in Alstom. “The big straightway with the gantry cranes on either side was a fantastic race straightway,” says Austerberry. “It looked, at night especially, like you were on some other planet. As soon as we saw it, we knew we had to make it work. The key was trying to create a full racecourse.”

The crew felt constructing the desolate hellhole of Terminal Island and the racecourse was like assembling a 3-D jigsaw puzzle. Because Anderson wanted to use actual locations versus a computer-generated island, the production designer had to create separate sets that would-when put side by side on film-create a contiguous world.

Anderson storyboarded the entire production, and he and Austerberry used a large-scale foam-core model to help the special effects and stunt teams, the DPs and the various units visualize the scenes for which they were prepping. “It took about a week with a huge crew of us going through the script bit by bit,” explains Austerberry. “You could physically locate elements on our foam-core model well in advance of actually prepping the locations.

“Repeating certain bits of Alstom to be different parts of the racetrack, we pieced it all together,” he continues. “We created a model, which sits in Hennessey’s office. When we shot a scene inside her office, half the crew looked at the model and said, `Oh, now we get it!’ They could really see the whole lay of our fictitious land.”

This systematic jigsaw-puzzle approach allowed them to choose which elements they needed to create the racecourse and prison on an oppressive island. “There were silos in the Old Port in Montreal, which had beautiful industrial architecture and surrounding water,” says Austerberry. The key was selling the fact that we were on Terminal Island.” Coupled with Anderson’s notes to director of photography Kevan to shoot low angles-with just enough wide shots to suggest a menacing, overwhelming environment-the design offered a bleak war zone that crushed prisoners.

Another piece of the puzzle was found in the Bleeker Tunnel, a wide space that gave new depth to the Death Race. When he tied together visuals of the silos in the Old Port and the straightway in Alstom, Anderson had his behemoth racetrack.

For exterior shots of the Terminal Island prison facility, the team lensed at an abandoned, turn-of-the-century prison, St. Vincent de Paul. Though closed more than a decade ago, the massive exteriors and interior courtyards were exactly what was needed for the penitentiary. In fact, the jail reminded many in the production of the look in Franklin J. Schaffner’s seminal prison film Papillon.

Tyrese Gibson comments that locations were so realistic it felt as if they were in jail. “No acting was required,” he says.“You just had to look around, see the big, old walls and all the barbed wire to focus on what you were there to do.” There was, however, some break for the new inmates. Because interiors of St. Vincent’s were too moldy, decayed and dangerous in which to shoot, Terminal Island’s interiors were lensed inside the warehouses in Pointe St. Charles.

The actual steel mill used in the spectacular opening shot where we first are introduced to Ames added to the gritty reality. The production secured permission from the mill to shoot documentary-style in the working factory, with Statham placed among the real workers while enormous cauldrons full of molten steel were poured in the background.

Anderson and Kevan took advantage of the opportunity to lens a worker clad in a fireproof suit using a high-pressure hose to clean out a cauldron-complete with the residual slag-between shift rotations. Explains Statham, “I think they knew it was our last pour of the day, and they filled that sucker up. Literally, as they called `Action,’ I could feel the hairs on the back of my neck start to disintegrate. I swore a couple of times in the back of my brain and just kept a stoic face as I walked towards the camera.”

The resulting footage was so good, it almost doesn’t look real. In one key scene, Statham walks toward the camera and takes off his helmet as molten iron is poured behind him. It truly looks as if it’s a visual effect-the performer against green screen-but he was actually there.

The Cars of Death Race

The cars in the action-thriller are not just an extension of the men driving them; they are characters themselves. It was key to the production that the Death Race autos were insane modifications of expected models. It was like designing two movies in one; creating the cars was just as difficult as developing the characters.

Anderson and Austerberry worked with two concept illustrators to begin the process. “We had to pick cars you could easily recognize in the fray of the race-those that have different silhouettes,” explains the designer. “We also wanted cars that would appeal to a broad range of ages.”

The industrial character of the autos came from the gritty, bashed-up aesthetic, as these are machines built by the criminals. The actors loved their respective rides, complete with napalm, nitrous-oxide (NOS) tanks and ejector seats. Says Statham, who, as Ames, drives a tricked-out 2006 Ford Mustang GT known as The Monster-armed with a ¾-inch steel tombstone and two mounted mini-guns that spit out 3,000 rounds per minute: “The Mustang’s the signature all-American muscle car. Just the drawings were enough to seduce any man, so to get to see what was available behind the door…”

Gibson as Machine Gun Joe drives a weaponized, armor-plated 2004 Dodge Ram 1500 Quad Cab 4WD. His truck was designed to incorporate a Vulcan machine gun pulled from a helicopter gunship, which makes the car slower than the others but heavier all around. “It’s a big piece of metal, and that makes sense. My car was a reflection of my character in the movie,” says Gibson. “I have the biggest car because I’m a bully.”

Neo-Nazi Pachenko drives a 1966 Buick Riviera chop top, lovingly known as the “Death Machine.” “The arch-villain’s car is quite different; it’s like a Hot Wheels car,” says Austerberry, adding that inspiration came from a picture of a Riviera with a chopped-down roof in Hot Rod magazine. “We combined those things together and created Pachenko’s villainous car. It has a bright ’60s color on the side and matte charcoal gray on the top to squish it down, with a low roof and narrow windscreen.”

The other cars driven by Death Race principal competitors were a variety of fiendish makes and models. They include 14K’s 1978 Porsche 911, outfitted with four hellfire missiles on the roof and four mini-rocket clusters on the hood; Travis Colt’s 1989 XJS Jaguar V12 with two M2s (.50 cal.) on the hood front; Grimm’s 300 monster car, a 2006 Chrysler 300C with three MAG 58s (.308 cal.), rocket-tube machine guns on the hood front and hellfire missiles on the back.

Of course, the deciding factor in the design was maneuverability, but that didn’t mean drivers couldn’t die in style. Others who meet an early death in the race roll out in a 7 Series BMW (1989 BMW 735i) made to look like an aircraft cockpit. The design team imagined one-half would be cut out of it, and they put the navigator behind the driver (with a mini-gun on the side) to create a different silhouette. There was also a 1971 Buick Riviera “boat tail” with a pointed back nose, quite the contrast to Pachenko’s ’66 Riviera chop top-with its points on either side, front and back.

Alongside these beauties, Anderson commissioned a rebuilt 1979 Pontiac Trans Am with a cattle guard, 50-cal. gun on the hood front and .308-cal. mini-gun. They were designed to be painted in a way that kept them looking like battered, rusty machines that have seen and done some damage over the six years since the Death Race began. When all cars were lined up in the Bleeker Tunnel, they made an impressive sight.

Finally, Warden Hennessey has control over the biggest, meanest vehicle of them all. The Dreadnought is the monster of all monsters. It’s painted battleship gray and comes smoking down the track, guns blazing and fire spitting. With its flamethrower, six heat-guided rockets, PKM machine gun and wheels of solid Dayton Kevlar, the Dreadnought is designed as a weapon of last resort, to be unleashed in a fury of destruction whenever Hennessey feels the playing field is getting too…even or boring.

Building the Racers

It took approximately eight weeks of working through concepts before the team began assembling and set up in a Montreal fabrication shop. Explains Austerberry: “We had four draftsmen and two concept artists working in Toronto, then we came to Montreal. There was a huge team [50 crew members] who set up the auto fabrication shop, then we started getting the base cars, the real cars.”

Special effects foreman Jason Hanson and picture-car mechanic Brian Louis and his crew worked with 30 base cars to gut and get them ready for production. This meant destroying electrical systems, airbags and antilock braking systems. “We stripped them down to bare metal, then built them from the ground up, doing roll cages, fuel cells and racing seats,” he says. “Then the special-effects crew took over and did their body fabrication on the cars.”

Austerberry describes the high-tech process of translating the raw materials into a Death Race car design on computer. “A handheld 3-D scanner [known as AndiScan] was passed over the raw car itself. Then another team in the effects design shop took the concepts and drawings and elaborated on those in 3-D, so they could send them out for cutting and fabrication of the various pieces.” While that outsourcing took place, each base car was stripped of its gas tanks and a fuel cell was installed-as were safety features such as full roll cages that were fitted for specific stunts.

Jean-Martin Desmarais, special effects designer and fabrication manager, describes the efficacy of the AndiScan process (which takes approximately one-half day per car) as “highly accurate; it scans within a thousandth of an inch. It uses three optical cameras and three laser sources to find all the points on the surface that are being scanned. It weighs three pounds and scans anywhere you can get the scanner into.”

The 3-D modeling enabled DesMarais’ team to validate placement for all parts-from armored plates and racing seats to weapons-and to find potential conflicts among them. It also allowed Anderson to get a feel for the shots he would be able to achieve with each car…and the visibility actors and stunt drivers would have when driving. The process saved the production about three months of work, about how long it would have taken to hand-fit the 500 to 900 parts put on each of the cars.

It took approximately six weeks per car for the mechanics and fabricators to put the racers together, then another week to make the thin sheet metal that was used to imitate the thick-plate steel armor necessary to survive any blast from enemies. Death Race drivers wouldn’t last long without heavy armoring on their rides. Not to mention the fact that viewers get annoyed when a competitor is blown apart in two minutes.

To account for the armor and guns added onto the cars, Louis and his crew added in heavy-duty suspension. To illustrate, he offers: “On the Dodge Rams, we changed over from a 1,500-pound to a one-ton rear dual axle to take all the weight. On those, we added almost 2,500 pounds with the steel, guns, excess ammo batteries and whatnot in back of that truck. The cannons on the back are almost 800 pounds-just between the two Vulcan cannons on each side of the Dodge.”

Explains Martin Mandeville, in charge of building interiors for The Monster, “The inmates scrounge and make cars with whatever they can find, so it was appropriate for us to make this up with stuff from the scrap yard.” His team used a variety of parts, including those from other modes of transport. “I found aluminum aircraft parts and built the napalm dispense. There’s also a series of tanks used for defensive weapons.” The ejection seats were another main feature of Frank’s Monster and play into the story arc. As an actual ejection seat can be quite mammoth, Mandeville simplified its elements so Frank could feasibly eject a couple of seats from his Mustang.

In total, 34 cars-including six Mustangs, five Dodge Rams, four Porsches, three Jaguars, three BMWs and three of each-style Buick-were used to portray the 11 main cars and a few extras from the Death Race. The Fords, Chryslers and Dodges were primarily acquired from manufacturers, while the Rivieras, Porsches and Jaguars were secured online. Additional cars were found through auto-trader magazines.

Building (then arming) the bombastically loud and lethal Dreadnought was a massive task: two tractors were shipped from L.A., and the shell of a tanker was obtained in Canada. The Dreadnought was built in Calgary in a shop with facilities to contain the colossus. Nigel Churcher, in charge of the process, notes: “We wanted it to seem as if it was a reconfigured existing truck, as opposed to something that had been specifically designed and built so that it would suit the rest of the film.”

Though the crew saw pictures of the Dreadnought before it arrived, no one, including Anderson, knew what was coming. The noise of the guns, blazing at once, was deafening. The concussion shook the cast and crew, who cheered when it first drove by.

Arming the Death Race Cars

As head armorer, it was Charles Taylor’s job to weaponize the cars. “The challenge was to take firearms never meant to be mounted on cars and mount them on cars like the Dodge Ram,” explains Taylor. “In the original artwork, they had big Vulcan cannons on the side. They didn’t know they were actually available to put on the car. I said, `A friend of mine has two of them, and I can make it work.’”

Originally, the production intended to fake the weapons’ gunfire, but Taylor convinced them otherwise. “There’s no better way than to just fire them the way they were meant to be fired,” he says. “We put a very simple mechanical or electrical system in, based on the type of gun, so that it would fire the way it was supposed to.”

He asserted that, to achieve the proper effect, it should be very noisy. “It had to be that loud because it had to have that kind of pressure to make the guns operate,” Taylor states. “On the Ram, we had four 30-caliber 1919 machine guns, along with the two 20 mm Vulcan cannons. That firepower alone would make anybody that knows weapons say, `Oh my God, what’s on the next one?’”

The loudest of all, though, had to be Hennessey’s Dreadnought, commissioned by the warden to be created purely for destruction and ratings grabs. With huge, extremely noisy guns, the Dreadnought’s weapons were the most impressive guns to fire because the muzzle flash was so large. Taylor mounted a full-on arsenal on the Dreadnought.

He explains, “You have the cowcatcher on the front and two M3 high-speed, .50-caliber machine guns on the hood. In the sleeper cab are two M134 mini-guns, and then on top are a .50-caliber machine gun in the front and a .50-caliber machine gun in the middle. Underneath that is a flamethrower. In the back, there’s a 76 mm tank turret, and-on top of the turret-is the PKM machine gun. When this thing lights up and is firing all guns and using the flamethrower, it’s beyond impressive. It’s hell on wheels.”

Crashes and Fights: Filming the Stunts

Cast and crew of Death Race would not leave the production without their fair share of bumps and bruises. The cars, however, would barely exit the track on all four wheels after the punishment they received at the hands of the stunt team and second unit.

Bolt discusses how three units were used to film Death Race: “We had a splinter unit, first unit and second unit. The second unit, running parallel to the first unit, was directed by Spiro Razatos. He executed the action very specifically, carrying out Paul’s storyboards. Paul directed all the drama and actors, and we had a splinter unit hovering in all the inserts-feet on accelerators, rev counters, steering wheels…all of those small pieces that really make up a movie.”

Lensing the Races

With multiple autos racing at top speed, there were many challenges during filming. Some spectacular stunts could only be done once, so Anderson’s team shot as much footage as possible. Up to eight cameras shot from multiple points of view-both in the air and on the ground. Cameras were rigged in crash boxes to protect them from impact, fire, heat and debris, and mounted on the cars so they’d be in the middle of the action. Often, the second unit was just outside the windows of cars zooming by.

For the writer/director, shooting Death Race offered a nod to another era of filmmaking. “In the 1970s and ’80s, there was a limit to how close you could get the camera to some of these crashes,” Anderson says, “a limit to how much you could move the camera. We’ve built a load of unique rigs that have never been seen before in movies-built specifically for this film. We were able to get the camera so close to these real crashes, these real explosions-cars on fire, cars spinning 20 feet in the air-all done practically and all done safely.”

In order to implement his vision of a deadly place and time, Anderson worked with a seasoned film and stunt crew. Second-unit stunt coordinator ANDY GILL notes: “Luckily, everything we could do in the physical world, Paul wanted to do. For a lot of big wrecks, we had some effects wirework that helped with the stunt work, but we tried to keep it as real as we could. We stayed away from the special and visual effects for flipping cars through the air…unless it was physically impossible.”

To keep stunts organized, Gill created diagrams of all the races, which he color coded to indicate details such as which cars would explode and how many bullet holes they had in them each lap. Matchbox cars were used to block out the action in miniature.

When the team needed to make actual cars blow up, it built some that didn’t need human drivers. “We got with special effects to build these rigs: remote-control cars,” explains Gill. “When we needed to shoot at high speed and have a very violent wreck with the cars ripping themselves apart… we didn’t put stunt people in.”

The other Gill on the set, Andy’s brother Jack, was the lead stunt driver. He drove the 600-horsepower, “new muscle car” Mustang and worked with the other stunt drivers (and actors when at the wheel) to secure all moves were done safely. It was mandatory, as, for instance, the Ram had very limited visibility and the size of the window in the chop top is approximately 3 inches tall.

Jack Gill says they employed all kinds of special driving tricks and stunts to make the races look spectacular. “The reverse-drive rig is something we’ve been using for about five years. It’s an ingenious little thing where you hook up a steering wheel and a set of pedals and a brake in the back of the car so that another driver can sit in back and look out the back window.” The reverse-drive rig allowed the stunt crew to create spectacular driving action as, essentially, two guys drove for one stunt.

To keep the story in sync, it was crucial to get shots of the actors in the cars driving. Statham did a lot of his own wheelwork, but often he and the actors needed help. Jack Gill had the perfect solution: the pod car. He describes the invention as “convenient when you want to get actors’ reactions-ones you can’t get on green screen-in real traffic and in actual cars banging together. The pod sits on top of the race car and is attached to the car with a steering wheel, brake and accelerator pedal. I drove up there while the actors sat inside with cameras pointing at them.”

This many fast, exploding cars posed plenty of danger, and, because of the amount of fire and explosions, the stunt team wore three-layer fire suits at all times. Empty shell casings from the firepower also offered hazards such as punctured tires.

To keep things moving, a mobile pit stop was set up off camera, and a crew of mechanics worked throughout the night to prepare the cars for the next day. “Every day we’d start off in the morning by getting all the cars prepped,” explains Louis. “Going through each car, making sure they’re all safe. Then, at the end of the day, we actually brought the cars back to a night crew. Those guys worked all night long to repair all the damage we inflicted.”

Creating the Fights

While exploding cars were left to the stuntmen, actors did a good amount of their own driving and fighting. The fight scenes needed to be as violent and real as car scenes, and Anderson called for a level of subtlety and basic physicality from the actors. “I’m used to doing very stylistic fight scenes,” explains Statham. “I didn’t think that was suitable for the Jensen Ames character. He’s a race driver, not a martial-arts expert, and he’s not someone with Special Forces tactical training.”

Though the actors’ environment was broken-down, the roles in Death Race required them to bulk up to portray the hardened men of Terminal Island. To physically realize the character of Jensen Ames, Statham trained for months with Logan Hood, an ex-Navy SEAL. Hood, one of the key trainers on 300, knew a thing or two about getting men into fighting condition.

The first time we see the level of Ames’ skills (and the months of Statham’s training) is in the penitentiary’s mess hall. To inform his role, Statham visited Corcoran State Prison in California-the current residence of Charles Manson-during preproduction. As Statham discovered during his trip: “You walk into the mess hall and see this sign: `No Warning Shots.’ There are guards with guns walking around. If any skullduggery takes place, they are the first people to quell that kind of nonsense.”

Fight coordinator Phil Culatto, Statham’s stunt double on Transporter 2, filled in the moves to create that explosive fight-a process that took about two weeks before the final version of the scene was locked. Culotta says that he relied on the basics to make it look like a dogfight. “To keep it down and dirty, we tried to make each hit be a `done hit.’ You get hit in the face at full steam by Jason Statham-just a gigantic rip-then, you’re done. We end up trying to grab everything, including the kitchen sink, and just hit people.”

The fight in the auto shop-where Ames is jumped by the neo-Nazis, slammed in the head with a pipe and choked with a chain-also required that Culotta choreograph substance and raw style. “For the prison auto-shop fight scene, we wanted to make it realistic and incorporate some of the things that you would use in the auto shops,” Statham explains. “Some props we got our fingers on were great: fire extinguishers, big pipe wrenches…there’s even chains you were getting choked with.”

****

Filming wrapped, a weary Death Race cast and crew reflect on their experiences and hopes for the action-thriller. “It’s a very adult form of entertainment and certainly plugs itself into what my taste is all about,” Statham says. “You got hot chicks, boys being boys; what more do you need?”

We conclude our notes with a parting comment from the filmmaker, who was so inspired by the cult film as a boy. Anderson sums: “In Death Race, I want to stay true to the slightly irreverent tone of Death Race 2000 without becoming intentionally campy. I want to tell a more serious story and have it be a darker movie, still with comedy in it. I made a very different film but one that still has a little social commentary in it. Just like the original Death Race did.”

Production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

Death Race

Starring: Jason Statham, Tyrese Gibson, Joan Allen, Ian McShane, Natalie Martinez, Jason Clarke

Directed by: Paul W.S. Anderson

Screenplay by: J.F. Lawton, Paul W.S. Anderson

Release Date: August 22, 2008

MPAA Rating: R for strong violence and language.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $35,952,880 (73.8%)

Foreign: $12,736,636 (26.2%)

Total: $48,689,516 (Worldwide)