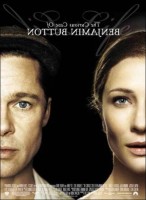

Adapted from the 1920s story by F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is set in New Orleans from the end of World War I in 1918, into the 21st century. It follows the life of Benjamin (Brad Pitt), who is born with the appearance and physical limitations of a man in his eighties.

Abandoned in a nursing home by his father, Benjamin begins aging backward. While in the home, he meets Daisy (Cate Blanchett), a young aspiring ballerina. As the film progresses, the two fall in love, while struggling to deal with the issue of one growing younger while the other grows older.

“The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” began its life as a short story written in the 1920s by F. Scott Fitzgerald, who, in turn, drew his own inspiration from a quote by Mark Twain: “Life would be infinitely happier if we could only be born at the age of 80 and gradually approach 18.”

Fitzgerald’s story was a caprice, a find of fancy, and bringing it to life on the screen was long perceived as too ambitious, too fantastical to accomplish. The project floated around for 40-some odd years until producers Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall took it up. For over a decade, the project has likewise intrigued Eric Roth, David Fincher and Brad Pitt.

For Roth, the concept became an opportunity to introspectively view the broad canvas of a life through the synthesis of intimate moments experienced every day, through events that may be as large as a world war or as small as a kiss. “Eric was the ideal person to fully realize the potential of such a large-scale but deeply personal story,” Kennedy notes. “In ‘Forrest Gump,’ he revealed intimate portraits against the backdrop of epic stories, and a gift for richly observed detail.”

The chance to live life backwards would seem ideal. “But it’s not that simple,” says Roth. “On the surface, you think it would be just lovely, but it is a different kind of life, which I think is so compelling about this story. Even though Benjamin is going backwards, the first kiss and the first love are still as significant and meaningful to him. It doesn’t make any difference whether you live your life backwards or forwards – it’s how you live your life.”

While conceiving and writing the screenplay, Roth experienced the personal loss of both of his parents. “Their deaths were obviously very painful for me, and gave me a different perspective on things,” he notes. “I think people will respond to the same things in this story that I responded to.”

The movie explores the human condition that exists outside of time and age – the joys of life and love and the sadness of loss. “David and I both wanted it to feel as if this was anybody’s story,” Roth says. “It’s just a man’s life – that’s what’s sort of extraordinary about the movie and very ordinary at the same time. What affects this odd character affects everyone.”

While Benjamin’s predicament is entirely peculiar, his journey highlights the complex emotions at the core of every life. “It touches on questions we ask ourselves over the course of a lifetime,” says Marshall. “And it’s rare that one movie will elicit so many different, personal points of view. Someone in their 60s or 70s will look at the movie one way, while someone who’s 20 is going to see it another way.”

Producer Céan Chaffin recalls that the project had long been circling around Fincher, away from him and back. An earlier version of the screenplay sat on his desk when Chaffin started working with him in 1992. “It was something he loved and kept bringing up over the years,” she says. “I remember, too, when Brad asked him about it, and David said, ‘That could be a great movie.’ Scripts come and go, but this script never left. He says things go away for the right reasons and you can’t have regrets. This one must have had the right reasons to stay.”

Fincher’s own experience of loss infused his fascination with the story. “My father died five years ago, and I remember the experience of being there when he breathed his last breath,” he reflects. “It was an incredibly profound one. When you lose someone who helped form you in a lot of ways, who is your ‘true north,’ you lose the barometer of your life. You’re no longer trying to please someone, or you’re no longer reacting against something. In many ways, you’re truly alone.”

Early in the film’s preparations, Fincher’s meetings with Kennedy and Marshall often turned highly personal. “We’d start talking about the story,” Fincher remembers, “and fifteen minutes later we’re all talking about people that we’ve loved who have died, and people that we loved who didn’t pay attention to us, or people we chased or who chased us. The film is interesting in that way; it had this effect on all of us.”

Making the movie would be an ambitious jump, posing dramatic as well as technical challenges. “How do you deftly and succinctly create the experience of a life, with all its dips and peaks, from grave to cradle, within a single film?” muses Kennedy. “In Eric’s script, each moment accrues emotions that resonate with you later on. Cheating that sensibility would diminish the experience, so we knew from the beginning that it would take time to project the experience of a whole life.”

For Pitt, the only way to play the character was all the way through, at every age, which posed one of the film’s most daunting challenges. “Brad was only interested in playing the part if he could play the character through the totality of his life,” Fincher explains. “Kathy and Frank were more than mildly curious how we were going to do that. I said, ‘I don’t know, but we’ll figure it out.’”

Pitt’s draw was also in the journey Benjamin takes. “Many actors weigh a part based on what their character gets to do,” says Fincher. “Well, Benjamin doesn’t ‘do’ a lot, per se, but, man, he goes through an enormous amount. Brad was the perfect person. It’s the kind of role that would be passive in lesser hands.”

To share the screen opposite Pitt, Fincher cast Cate Blanchett. The director had Blanchett on his mind since catching her performance in “Elizabeth.” “I remember going to the Sunset 5 and just thinking, ‘Who is that? My goodness,’” he recalls. “You just don’t see people who have that kind of power and ability every day of the week.” The actress, says Pitt, “elevated most of our performances. She’s exquisite. She’s a great friend. She can read a scene like few actors can. I find her to be grace incarnate. I liked that she was playing a dancer. It fit her because of who she is, because of her undeniable elegance.”

The relationship between her character Daisy and Benjamin evolves as she comes to understand and learns to live with his preternatural circumstances. Notes Eric Roth, “Cate embodies this woman, who has to make peace with the idea of growing older while the person she loves is on the backward path. What does life become for her then? She goes from being an impetuous, passionate dancer to a woman with deep reserves of strength.”

Blanchett shaped Daisy with a dancer’s manner and passions, though the actress’ own ballet practice ended in childhood. “When I was a child, I did the usual girly thing and studied ballet but had to choose between that and piano lessons,” Blanchett notes. “I chose piano and then gave it up for drama. I have a great appreciation for dance, but know my limitations. This movie was a great opportunity to revisit that appreciation.”

Daisy is one of many figures that come into contact with Benjamin. “Benjamin is like a cue ball and all the people he collides with leave marks on him,” says Fincher. “That’s what a life is – a collection of these dents and scratches. They are what make him who he is and not anyone else.”

“I like this idea of dents,” adds Pitt. “People make an impact and leave some kind of an impression. There’s something very poetic and accepting about that. It doesn’t mean you roll over. It doesn’t mean you don’t fight for what you want. It means you accept the inevitabilities of life. People come and go. People leave, whether by choice or by death. People leave as you yourself will someday leave – it’s the inevitable. How you deal with this becomes the question.”

Pitt associates this notion with his friend and frequent collaborator. “The film explores this idea that I know to be true of Fincher — the belief that we are responsible for our own lives,” the actor says. “We’re responsible for our successes and failures and there’s no one else to blame or take credit for them. Fate certainly has a say, but at the end of the day, its shape is ours.”

The role presented Pitt with a complex challenge unlike any he has faced in a film – to communicate the character’s inner growth as he reacts to others he encounters throughout the film. “Benjamin Button’s journey is a very interior one,” says Blanchett.

“Despite the obvious physical demands the role placed on Brad as an actor, the trick was playing a character that listens and is present and reactive to everyone in the movie.” “It’s perhaps the stillest performance Brad has ever given,” Fincher adds.

Roth points out that Pitt also grounded the extraordinary aspects of the character with his own essential humanity, “The bravura of this performance is that Brad plays him as this sort of ‘everyman.’ I think from his own life, Brad found an affinity for this character that transcends acting the role. He understands what it’s like to live a different kind of life.”

As Benjamin’s adoptive mother, Queenie, tells him throughout his life, “You never know what’s coming for you.”

Benjamin is born in New Orleans in 1918, at the end of the Great War – a good night to be born. When Benjamin’s mother dies in childbirth, his father, horrified at his appearance, abandons the baby on the steps of Nolan House, a retirement home where he is taken in by Queenie, the home’s caretaker.

Taraji P. Henson was pegged for the role of Queenie long before the film came to fruition, when Fincher’s casting director, Laray Mayfield, steered the director toward her performance in “Hustle and Flow.” “We were all taken with how alive and maternal she was,” Fincher recalls. “I found all the warmth, all the non-judgmental aspects of Queenie, in Taraji.”

Queenie does a job many people could never do. “She’s a woman who knows how to deal with death,” says Henson. “And, at the same time, she is the embodiment of unconditional love. To be able to take in a child that’s not yours, at a time when racism is the norm, and he’s white and has been born under these unusual circumstances – she is able to look past all that and love him.”

The character spoke to Henson on an intensely personal level. “It’s been a very spiritual journey for me,” she reveals. “I had just lost my father, and even though I miss him dearly, it’s almost as if his death was a part of my journey towards Queenie. When my father was sick, we made sure that he was never alone; someone was always at his bedside. He passed away while I was with him because he knew I could handle it. This role helped me through my grief and my grief helped shape my performance. Art can be very healing.”

Benjamin grows into adulthood with an equanimity towards loss that few experience. “He comes from a world of people who have made peace with their own mortality, so there’s not a lot that scares him,” says Fincher. “Every person he meets is transient; every moment with them could be his last. Yet, none of the people there are hysterical; they’re all making do. So, by a very young age, he is familiar with the most profound aspects of death. It’s coming for everyone, and we spend all our lives focusing on other things to avoid having to think about that inevitability.”

Benjamin first meets Daisy when they are both children and she comes to visit her grandmother at Nolan House. Daisy sees through the exterior of his elderly handicaps to the child beneath. “One of the linchpins of the piece is how their lives coincide and differ,” says Roth. “This relationship evolves as they grow and change, with all the missed and found opportunities in between.”

While everyone around him is growing older, Benjamin is growing younger, all alone. “Benjamin aging backwards only makes him more aware that you can’t hold onto things,” says co-star Mahershalalhashbaz Ali. “He knows that you have things for a certain amount of time, and then you have to be okay with letting go. You can take what you can from it while it’s here, but it’s never yours.”

This sense of acceptance is a trait Fincher traces back to his own father. “I see a lot of my father in Benjamin,” the director says. “As a journalist and a product of the Great Depression, my father was a bit of a stoic, an observer; he took things in without judgment. I remember him as being happy to appreciate people as they were. I filtered that in Benjamin’s reactions and especially the way he dealt with people, with situations. I’d look at him and say, ‘Yes, Jack would do that. He would act that way.’”

Along with Queenie, Benjamin is raised by the elderly men and women whose adventures and life lessons are behind them and who have come to Nolan House to quietly spend their twilight years.

Tizzy Weathers, Queenie’s longtime love, is one of Benjamin’s first “fathers.” “Tizzy is kind of a flag post, a barometer for his manhood,” says Mahershalalhashbaz Ali, who plays Tizzy. “He helps to guide him and raise him. He teaches him to read and to write; he teaches him about Shakespeare. But I think he mostly leaves him with a sense of what a man is. Tizzy gives him that foundation so there can be some chance at peace for Benjamin in regard to having a male figure in his life.”

But Tizzy, like everyone Benjamin comes to know and love, is only his for a short time. Benjamin leaves behind Queenie and Tizzy, Daisy, and his collection of friends from the only home he has ever known when he lights out for the world. The person who presents him with an invitation to adventure is Captain Mike and the motley crew of personalities on his tugboat.

Jared Harris plays the grizzled sea captain, who reveals his secret self through the map of tattoos covering his body. Harris describes his character as “sort of a thwarted, frustrated, drunk, angry failed artist, in a way. He went into his family business because he couldn’t stand up to his own father.”

In spite of his own father issues, Captain Mike becomes another “father” to Benjamin. “Your father is a tremendously powerful figure in your life,” says Harris. “And within this story, the male characters – the relationships between fathers and sons – is a massive underlying thread. Captain Mike introduces Benjamin, in that sort of bad father/uncle way, to the vices and pleasures of life. He also introduces him to a life at sea, and through that life, Benjamin gets to see the world.”

But Captain Mike, like Tizzy before him, is a stand-in for the real thing – Thomas Button, the father that left Benjamin on Queenie’s doorstep. “Thomas transfers all his sadness, resentment and fear of the future to the child,” says Jason Flemyng, who plays Thomas Button. “In a strange way, after losing his wife in childbirth, Thomas believes he’s ridding himself of all the heartache by leaving his son behind, but in fact, he spends the rest of his life regretting that act. It haunts him forever.”

Flemyng, a friend of both Pitt’s and Fincher’s, was so taken with Eric Roth’s script that he immediately put himself on tape after reading it in attempt to land the role of Thomas Button. Flemyng recalls, “I was excited for Fincher and Céan Chaffin to see what I could do with this part. I knew this would be the kind of movie that I would go to the cinema to see. I just really wanted to be a part of it.”

Benjamin comes of age in the far-flung Russian port town of Murmansk, where he meets another defining personality – Elizabeth Abbott, played by Tilda Swinton. “Tilda has proven time and time again that she can do anything,” says Kennedy. “The opportunity for her to hold the screen with Brad, Cate, Taraji and all the other wonderful actors contributed to the tremendous wattage of the film as a whole.”

The lonely Elizabeth Abbott, wife of a diplomat, who harbors dreams of swimming across the English Channel, becomes Benjamin’s first kiss. “They each learn something from the other,” Swinton says. “She is open, energetic and self-searching; he is patience, simplicity, and optimism. It is a fair exchange. The idea of her, at the end of her life’s adventure, being affected by Benjamin’s sense of beginning – of living with the newness of independence and of choice, of claiming one’s own life for oneself – is something I find very moving.”

Throughout Benjamin’s travels on the tugboat, Daisy’s own trajectory brings her to New York, where she joins a dance company in the prime of her young life, brimming with emotion and pushing boundaries. “This isn’t a ballad of co-dependency, which is ‘I can’t live without you,’” says Fincher. “They’re not waiting for each other. They’re both sexually active. These are two complete individuals who choose to be together for a certain amount of time, even though it is not the easiest way to go.”

Their paths will diverge and converge throughout their lives, until they reach what Fincher calls the “sweet spot” in the middle when they’re meant to be together. “The universe conspires to make them who they are at exactly the right moment,” he says. “And you kind of breathe a sigh of relief when they get together because now it can happen, exactly as it is supposed to.”

Daisy, and all of the personalities that populate Benjamin’s world, have their own life arcs over the course of the tale. Their stories, in tandem or out of frame, are indelible threads in the tapestry of the film. “I think David has the artist’s sense of holding the actual material of filmmaking in his own hands,” says Swinton. “His sleeves are up. He perceives both the traditions of Hollywood cinema and what he sees as its pretty limitless possibilities, all with the attitude of a true pioneer. He’s like a child in a sandbox. There is a sense in which the images he builds with his colleagues are simply downloaded from the film that exists, fully formed, in his own head. It feels as if he’s piecing together his taste of the film in an elaborate game: as if he was remembering a dream. Wonder seems never very far away for him.”

Pitt concurs, noting, “David is like a man possessed. He’s got such an eye for film and the balance and ballet of a camera move that it cannot be any other way for him but superb. The great reward is that you have this finely sculpted piece at the end. He is a sculptor.”

“He circles an idea, a moment, an image, a character or a scene, viewing it from all angles and, where other people are satisfied when they have viewed the idea in three dimensions, David wants to keep investigating until that idea has six or seven dimensions,” adds Blanchett. “When other people would say, ‘Stop David, that’s impossible,’ it only spurs him on. I do think many other filmmakers would have stopped short of the incredible places David took this fable – and us.”

“The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” was shot in a variety of locations, including Montreal and the Caribbean, and the character’s home city of New Orleans, which was recovering from the devastation of Hurricane Katrina when production set down. “We had committed to film in New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina and, of course, there was a period of uncertainty about whether we would be able to shoot there following the disaster,” recalls Kennedy. “However, the city called us just two days after the hurricane, eagerly encouraging us to continue with our plans.”

Working in an area that was just coming out from under devastating emotional and physical damage presented some logistical challenges for the filmmakers. “With the overwhelming support of the city and the incredible talent of our cast and crew, these proved to be minor complications,” says Marshall. “Each day was carefully planned and rehearsed, and David’s leadership in all areas allowed everyone to have a clear idea of what was expected, so, overall, the shoot went very smoothly.”

The filmmakers quickly found that hardship had not dimmed the spirit of the people of the city. “I think Fincher and I were very fortunate that we got to work with people who were there because they wanted to be,” says Chaffin. “On this film, we had an extraordinary amount of ‘Yes, we would love to have you,’ particularly from Louisiana. Each person who read the script was touched by some part of it – and it was different from person to person. I think it reminded them of something in their own life and they had to be a part of this film.”

The timelessness of the city dovetailed with the tapestry of eras in Fincher’s film. “It was important to clearly delineate each era in the film without overtly announcing the passing of time,” says production designer Donald Graham Burt. “It was more important to create a sense of a natural progression of time within sets. [Set decorator] Victor J. Zolfo and I would discuss what elements on the sets we felt should change and which should be suspended in time. It was important for any elements to be purposeful and have reason, and not just be placed to fill a void or altered just for the sake of change.”

Fincher worked with the production design team to infuse the sets with a feeling like paging through a photo album from somebody’s attic, filled with portraits of simple folks living ordinary lives. “We created our own ‘life’ stories for each of these sets, in particular Nolan House and the Winter Palace Hotel in Murmansk [where Benjamin meets Elizabeth] – places where major events in Benjamin’s life occur,” says Zolfo.

The mandate at every level of the production was to create a believable realism that would nurture the essential truths at the heart of the story. “As much as there are a lot of fable conceits in this story, I wanted to err on the side of it being as realistic as possible,” Fincher explains. “I didn’t want it to feel like ‘Once upon a time.’ I didn’t want to let the actors off the hook. I didn’t want to let the audience off the hook. I didn’t want to let the production designer off the hook. Everything had to be up to period – what places would look like, what people would wear, what kind of glasses or hearing aids they’d have.”

The costumes were of the moment, but stylized. Costume designer Jacqueline West met with Burt and Zolfo early on to ensure the symmetry of their work. “David composes like a painter,” says West. “When I walked onto the railroad set, it looked like a Caillebotte painting. So, I went to Caillebotte and the other early Impressionists for my inspiration – Edouard Manet, Toulouse Lautrec, Courbet. I just knew that once I figured out Don Burt’s beautiful sensibility, whatever I put in there within my color palette, which was pretty dark and muddy, would work.”

West turned to the Depression-era WPA and FSA photographers, especially to gain inspiration for Queenie’s wardrobe during Benjamin Button’s early life. “Queenie is a poor woman who has a lot of character, so I wanted her wardrobe to reflect her personality,” she says. “I also figured that most of her clothes would be hand-me-downs from the old women who had lived in Nolan House and died there. These women had probably stopped shopping maybe 20 years earlier. So, I took her back in time a bit.”

By contrast, Daisy would always be dressed in the upcoming fashions and formfitting ballerina clothes of the era. For Daisy, West referenced pioneering dance choreographer George Balanchine and his wife and muse, Tanaquil LeClercq – an inspiration Blanchett herself had explored. “I looked at dance movements that were influential in Daisy’s youth,” Blanchett explains. “George Balanchine and Tanaquil LeClercq were of particular interest to me.”

Blanchett, says West, “became a ballerina in the fittings. She reminded me so much of pictures I’d seen of LeClercq – the body language, the mannerisms and the internal conflict.”

LeClercq favored the designs of Claire McCardell, one of America’s top designers in the 1940s and 1950s, who is credited as the originator of “The American Look.” West turned to McCardell for one of Daisy’s most memorable costumes – the flowing red dress she wears on her date with Benjamin. “Jackie was definitely my partner in crime,” says Blanchett. “I adored every stitch, every button. She introduced me to Claire McCardell and the costume fittings were a revelation. How blessed was I.” To dress Benjamin Button throughout his life, West referenced cinema icons of the 20th century. “I used Gary Cooper in the ‘40s; Brando in the ‘50s; and Steve McQueen in the ‘60s. They were great inspirations and Brad has that same kind of charisma, so I knew he could pull those looks off,” she says.

One other physical element for Pitt was the digital techniques that would facilitate his performance of Benjamin from youth to old age. Visual effects supervisor Eric Barba, a longtime Fincher collaborator, notes, “David told me from the beginning, ‘Brad has to drive the performance from beginning to end.’ Benjamin is the emotional core of the movie, and is clearly present, even when it seems impossible. That was our challenge with the effects.”

Barba worked in tandem with Academy Award-winning special make-up designer Greg Cannom, who created prosthetics to enhance the aging and de-aging throughout the film. Understated but meticulous attention to detail on a broad canvas extended to digital cinematography in the film. “David’s shooting style for the film takes on a sense of what David Lean exemplified with sweeping epic shots that capture a sense of place and time,” says Marshall. “The emotional poignancy of the film achieves its power through David’s use of the camera as the observer. He wants you involved in the character study, so the camerawork becomes more studied and calm. It’s not a film that requires quick cuts and visceral frenetic camera moves.”

“We wanted to keep it as naturalistic as possible,” says director of photography Claudio Miranda. “We tried to know where the source was going to be coming from, and then tried to bend it or play it. We did some shots where we just put light bulbs in the frame and let them light the scene. You normally cheat sources by putting in a light bulb, dimming it down so it’s not too much, then creating another light source just out of frame. I thought it was cool that we just let it be.”

The light sources change as the eras overlap and give way to one another. “There’s progression in the technology, going from candles to gas lamps and clear bulb incandescents to fluorescents,” Fincher explains. “There are some movie lights, but not a lot. For the most part, it was shot digitally to be able to utilize these kinds of light sources, and also to be able to move quickly.”

Occasionally, shots organically presented themselves, as in the spare, elegant shot of Blanchett dancing in the gazebo during her date with Benjamin in New York. “That shot on the gazebo was so simple. We saw that and said, ‘We gotta shoot here,’” recalls Fincher. “There was some question about what the background would be and I said, ‘Well, it’s a swamp out there, let’s get some steam or smoke and light up those trees and keep her in silhouette.’ We were trying for an old, classic Hollywood style, super simple. It looked like a music box.”

Fincher’s exacting sensibility and attention to such details provided the ideal compliment to his deep understanding of the truths at the heart of Benjamin’s tale. “Considering the epic scope of the story and deep emotional arcs, every choice he made was perfect and so rewarding for us to be a part of,” Kennedy concludes.

Production notes provided by Paramount Pictures.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

Starring: Brad Pitt, Cate Blanchett, Tilda Swinton, Taraji P. Henson, Jason Flemyng, Elias Koteas, Julia Ormond

Directed by: David Fincher

Screenplay by: Eric Roth

Release Date: December 25, 2008

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for brief war violence, sexual content, language and smoking.

Studio: Paramount Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $126,814,862 (38.9%)

Foreign: $199,500,000 (61.1%)

Total: $326,314,862 (Worldwide)