Tagline: It takes a hero to change the world.

The film centers on a 21-year-old who lives among a primitive tribe that survives by hunting a mammoth each year as the herd migrates through the tribe’s homeland. It was a time when man and beast were untamed and the mighty mammoth roamed the earth. A time when ideas and beliefs were born that forever shaped mankind.

“10,000 B.C.” follows a young hunter on his quest to lead an army across a vast desert, battling saber tooth tigers and prehistoric predators as he unearths a lost civilization and attempts to rescue the woman he loves (Camilla Belle) from an evil warlord determined to possess her.

From director Roland Emmerich comes a sweeping odyssey into a mythical age of prophesies and gods, when spirits rule the land and mighty mammoths shake the earth. In a remote mountain tribe, the young hunter, D’Leh (Steven Strait), has found his heart’s passion – the beautiful Evolet (Camilla Belle). When a band of mysterious warlords raid his village and kidnap Evolet, D’Leh is forced to lead a small group of hunters to pursue the warlords to the end of the world to save her.

Driven by destiny, the unlikely band of warriors must battle saber-tooth tigers and prehistoric predators and, at their heroic journey’s end, they uncover a Lost Civilization. Their ultimate fate lies in an empire beyond imagination, where great pyramids reach into the skies. Here they will take their stand against a powerful god who has brutally enslaved their people.

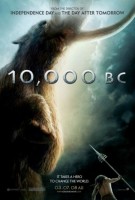

From director Roland Emmerich (“Independence Day,” “The Day After Tomorrow”) comes a sweeping odyssey into a mythical age of prophesies and gods, when spirits rule the land and mighty mammoths shake the earth.

In a remote mountain tribe, the young hunter D’Leh (Steven Strait) has found his heart’s passion — the beautiful Evolet (Camilla Belle). But when a band of mysterious warlords raid his village and kidnap Evolet, D’Leh leads a small group of hunters to pursue the warlords to the end of the world to save her. As they venture into unknown lands for the first time, the group discovers there are civilizations beyond their own and that mankind’s reach is far greater than they ever knew. At each encounter the group is joined by other tribes who have been attacked by the slave raiders, turning D’Leh’s once-small band into an army.

Driven by destiny, the unlikely warriors must battle prehistoric predators while braving the harshest elements. At their heroic journey’s end, they uncover a lost civilization and learn their ultimate fate lies in an empire beyond imagination, where great pyramids reach into the skies.

Here they will take their stand against a tyrannical god who has brutally enslaved their own. And it is here that D’Leh finally comes to understand that he has been called to save not only Evolet but all of civilization.

Warner Bros. Pictures presents, in association with Legendary Pictures, a Centropolis Production of a Roland Emmerich film: “10,000 BC,” starring Steven Strait, Camilla Belle and Cliff Curtis.

Directed by Roland Emmerich, from a screenplay written by Roland Emmerich and Harald Kloser, the film is produced by Michael Wimer, Roland Emmerich and Mark Gordon. Harald Kloser, Sarah Bradshaw, Tom Karnowski, Thomas Tull and William Fay are the executive producers.

The behind-the-scenes creative team includes director of photography Ueli Steiger, production designer Jean-Vincent Puzos, editor Alexander Berner, costume designers Odile Dicks-Mireaux and Renee April, and composers Harald Kloser and Thomas Wander.

A Hero’s Journey: The Story and Cast of “10,000 BC”

Visionary director Roland Emmerich has taken on everything from vast-scale alien wars to environmental catastrophe in some of the most successful blockbusters of the past decade, including “Independence Day” and “The Day After Tomorrow.” Now turning his camera to the distant past to create “10,000 BC,” the filmmaker faced his boldest and most ambitious filmmaking challenge to date.

Creating a new myth about a hero who emerges from an isolated tribe to challenge an empire, Emmerich sought to transport audiences into an adventure unlike anything they have experienced before, while stretching the boundaries of how a film should be defined. “I have always been intrigued by the idea of classic storytelling, in the timeless way people have told stories round the campfire for generations,” says Emmerich. “When your subject matter is early man, you have the opportunity to tell very rich heroic stories in which one character has to do the almost impossible. I wanted to make a movie that would allow audiences to fall into this other world that looks and feels like nothing they have ever seen.”

In order to take audiences on an adventurous journey to another time and place, Emmerich and his cast and crew first had to travel to the other end of the world. Production took them from the blistering cold of New Zealand in the winter, to the hot, humid climate of Cape Town, South Africa, to the arid desert landscape of the African nation of Namibia.

Producer Michael Wimer offers, “A filmmaker like Roland is always looking for something original, but it can be quite difficult to find a canvas that hasn’t been painted on, so to speak. It was an extraordinary challenge on every level-in fact, Roland said it was the most demanding movie he’s ever worked on. But I think the challenges are what a filmmaker like him thrives on.”

Harald Kloser, who co-wrote the film with Emmerich (in addition to executive producing and composing the score with Thomas Wander), notes that “10,000 BC” is a journey to a time when mysticism and the spirit world were a very real part of life. “Roland and I never intended for `10,000 BC’ to be a documentary,” Kloser offers. “Rather, we wanted to make a big adventure about the journey of mankind as they venture out and confront all these forces they can’t explain. We loved the idea of pushing the boundaries of what was possible.”

Making his third film with the director, producer Mark Gordon adds, “Roland is the kind of director who never wants to repeat himself. His imagination allows him to go places that most people don’t go. With the kind of stories he likes to tell, and his visual scope as a storyteller, he was the perfect director to make this movie.”

The film has all the elements of an action spectacle, depicting huge mammoth hunts, epic battles, and spectacular vistas of giant pyramids and lost civilizations, with interweaving threads of myths and mysticism. However, as Camilla Belle, who plays the role of Evolet, observes, “At the heart of the film is also a powerful human story. These two people, D’Leh and Evolet, are torn away from each other, and then have to find each other again, in the midst of this amazing journey. For them, and for the audience, it is really an escape into another world.”

“There’s something very beautiful about how the human condition hasn’t really changed over the millennia,” says Steven Strait, the actor who stars as the young warrior D’Leh. “What makes us human beings hasn’t changed since pre-historic times-love, compassion, conscience, sympathy. You see all of these things in this film. And you can relate to that no matter what era you live in.”

“There are legends and prophesies along with all the visceral elements,” comments fellow cast member Cliff Curtis, who plays the character of Tic`Tic. “There are predatory terror birds and saber-tooth tigers, and, of course, the mammoths, but the story also has a spiritual undertone to it, and I think that is the glue that holds it together.”

The story opens in a remote valley where the Yagahl tribe subsists by taking down one giant mammoth from among the massive herds that thunder across the land on their yearly migration. “The Yagahl are known as the mammoth hunters because they rely on these animals for their survival,” comments Emmerich. “The mammoths represent what the buffalo was for the Native Americans. On the one hand the tribe hunts it, but they also honor it; they feel blessed by it. It’s a very natural hunter/animal relationship.”

“The Yagahl live on the edge of survival, just barely living on what they can find and cull from the herd,” says Kloser. “Now they’re coming to the end of the Ice Age, so the climate is changing. They realize the mammoths don’t come as regularly anymore.”

The tribe is held together by its spiritual leader, Old Mother, played by Mona Hammond, and the hunter who carries the White Spear, who bears responsibility for feeding and protecting the tribe. Old Mother has seen the future of the Yagahl, and prophesied that a great hunter will rise and, with Evolet, lead his people to a new life before the mammoths disappear from the earth. No one believes it will be D’Leh, whose own father mysteriously abandoned the tribe when D’Leh was a child. They call him the son of a coward.

“D’Leh is the group outsider,” says Steven Strait. “He has been shunned by the rest of the tribe because of something that his father did in the past. They consider abandoning the tribe the most shameful thing a man can do, and D’Leh has to live with that legacy. But while it makes his life more of a challenge, it also gives him strength.”

“I’m drawn to father-son conflicts,” Emmerich says. “D’Leh has been abandoned as a boy, and like many boys whose father has run away, he has been stigmatized by his tribe and has a chip on his shoulder. He eventually learns that his father did it for a reason.”

After a casting search that spanned the United States, Europe, South America and New Zealand, Emmerich spied the ideal actor on a poster for an independent film called “Undiscovered.” The director recalls, “I saw Steven’s face and said, `Who is that?’ We screen-tested him, and also tested other people, but I always came back to Steven. He was just 18 at the time, and when he started this film he was good but not quite so sure of himself. I was very proud of him because, like D’Leh, he makes a total transformation in this movie. He had to essentially carry the movie, and he did. It was an amazing thing to see.”

Strait was excited about the prospect of working with Emmerich. “I’m a big fan of his films so it was thrilling to have an opportunity to work with him,” the actor says. “Roland is first and foremost a storyteller; even his most spectacular films are driven by the characters. When I read the script, I remember thinking what an extraordinary adventure it was, and making the film was an adventure beyond anything I ever imagined.”

D’Leh’s adventure begins with the introduction of another outsider to the group, Evolet, a refugee from a tribe that has been taken by what they called “four-legged demons.” “She is found in the mountains clinging to a dead woman,” says Emmerich. “Before the tribe finds her, they believed they were alone in the world. She is the first sign of other civilizations.”

Old Mother believes that Evolet is the key to the prophesy — she is inextricably tied to the hunter who will inherit the White Spear and lead the tribe to a new land. Though no one believes D’Leh will be this man, he forms a secret bond with Evolet, his fellow outsider. “Evolet is an orphan and was taken into the tribe as a child,” says Camilla Belle. “She’s in love with D’Leh and he’s in love with her. She wants to run away with him, but he knows they can’t. They’re like Romeo and Juliet, because Old Mother believes Evolet is destined to marry someone else.”

Michael Wimer notes that Camilla Belle possessed the exotic qualities they sought for the character and recalls that they were immediately struck by her in their first meeting. “When Camilla came in for the reading she had on some very interesting jewelry and I assumed she’d put it on for our benefit. But then I realized it was her own style. She is extraordinarily beautiful and talented, but she also brought so much strength to the role that it took your breath away.”

Mark Gordon agrees, adding, “Camilla has a vulnerability but at the same time you believe she could rise to the occasion and become heroic. Despite what happens to her, she’s not a victim.”

Belle posits that the character’s journey in the film brings out her inner strength, offering, “It took me some time to find a way to portray her strength. I wanted her to be someone young girls can look up to as a role model rather than just a damsel in distress because she’s really fighting not only for herself but for her people, too.”

The man who inherits the White Spear from D’Leh’s father and must pass it along to the tribe’s next leader is Tic’Tic, played by New Zealand native Cliff Curtis. “Tic’Tic has two purposes: one is to oversee the handing of the mantle of leadership to D’Leh; and the other is to fulfill the mythology and the prophecy that D’Leh and Evolet will lead the tribe to survival,” says Curtis. “Tic’Tic is a traditionalist. He believes in the mythology and in the prophesy. He believes in this young man, and he ultimately believes in D’Leh’s love for this young woman and that their destinies are intertwined. The fun thing about the character for me was that I didn’t play him like a wise old guy with all the answers. He’s grumpy and scary. He’s much more of a reluctant mentor.”

Emmerich notes that like his character, Cliff Curtis became somewhat of a mentor to his younger costar Steven Strait. “D’Leh is a character who is unsure of himself; he doesn’t know what he should do, and this adventure forces him to discover his destiny and who he really is. It was so amazing how Cliff Curtis, who is a very experienced actor, took Steven under his wing. They played so well off each other because the relationship between the characters really reflected what happened in real life.”

D’Leh and Evolet’s only friend, Baku, is played by British newcomer Nathanael Baring in his motion picture debut. “Baku is very young,” Baring offers. “He’s desperately trying to impress D’Leh and Tic’Tic and really wants to become part of the gang, but he ends up actually getting in the way more than helping.”

When the “four-legged demons” — slave raiders on horseback — descend on the tribe and brutally kidnap its young, including Evolet, D’Leh vows to pursue them as long as it takes to rescue them. “They come on horses, and they feel like demons,” Emmerich explains. “They’re so overpowering the Yagahl have no chance. In a way it’s D’Leh’s call to action. They take Evolet, and D’Leh has to follow her.”

Though he has given up the White Spear, D’leh refuses to back down, and is ultimately joined by Tic’Tic and his rival, Ka’ren (played by Mo Zainal), with young Baku also refusing to be left behind. Their treacherous mission takes them across snow-swept mountains into a Lost Valley, where they must do battle not only with the slave raiders but with mysterious terror birds that stalk them for prey. “In the Lost Valley there is a flock of terror birds living on this high grass,” Emmerich describes. “They’re somewhere between dinosaurs and ostriches, but they hunt like sharks, coming out of the grass and disappearing again.”

Eventually, their journey takes them to a new tribe — the Naku — and its leader, Nakudu (played by Joel Virgel), whose own son was also taken by the slave raiders.

Starving, dehydrated and in conflict, they ultimately reach a desert plain where giant pyramids cut into the skies and legions of slaves labor in fear of a being that calls himself a god. “For me, the pyramid is a symbol of total arrogance,” says Emmerich. “It contrasts perfectly with the lifestyles of the mammoth hunters, who have deep respect for the animals they hunt.”

To take on the brutal culture that has enslaved his people, D’Leh must cease to be a hunter and become the leader he was destined to be. “D’Leh has to pretty much go to the end of the world to rescue Evolet,” Emmerich continues. “But through this journey, he learns that he has to take responsibility for more than only this girl.”

Rounding out the international cast are Marco Khan as the slave raider One-Eye, and Ben Badra as the chief slave raider, Warlord. “We cast a wide net and chose an ensemble of actors for these roles who project such rich, different looks,” describes Emmerich. “These actors were of Asian, Latin, Indian, African and other origins. This film is about the landscape of faces, and I think we got some incredible faces.”

The filmmakers were also honored to have legendary Egyptian actor Omar Sharif serve as the narrator for the film. “He brought all the weight of his experience and history and humanity to telling this story. It was a real revelation to have him,” states Wimer.

To portray hunter-gatherers who lived their lives outdoors, a number of the actors engaged in a training regime at a boot camp in Cape Town, South Africa, overseen by stunt co-ordinator Franklin Henson. In addition to standard physical fitness, their training encompassed learning particular dance and fight movements that would be appropriate to the characters. For Nat Baring, this would involve scaling trees for his stand-off with the terror birds. For Strait and some of the other mammoth hunter characters, it meant learning the movement of the hunt.

Strait, who had bulked up for a previous film, lost more than 30 pounds of muscle through diet and training to portray the sinewy hunter D’Leh. “There are no written references about the way people were then,” says the actor, “so I looked at tribal cultures around the world. Not only did I learn about how they lived, but I based my body movement and gait on the idea that these tribes would have been hunting for food their whole lives. Their athleticism was about survival, so most of the training I did to lose the weight involved running.”

For actors portraying the slave raiders, physical training required extensive horse work as well. Horse master Peter White was responsible for training not only the actors but also the horses. White had 20 horses under his protection brought in from stables around Cape Town. “They were mainly crossbreeds, which have better resilience to disease, and they’re also less temperamental than thoroughbreds,” White relates. “We spent quite some time getting them used to what they were going to experience on the set: cameras, lights, smoke, fire and so on.”

When it came to the actors, White was required to get them comfortable with using sticks, swords, ropes and nets — all of which required one-handed riding — as well as bulky equipment and costumes. “The costumes had bodices which were hard and quite restrictive and made bending very difficult,” White says. “The saddles were normal, lightweight saddles, which made it more comfortable for riders and horses, but they were rigged up with bags and skins.”

From Cape Town, the horses were taken on a four-day trip to the Namibian locations, where they were held in a quarantined environment to minimize the risk of infection from native horses. With the dry environment of the desert, White also had to keep constantly vigilant that the horses were well-hydrated.

White faced different challenges when the film started its shoot in New Zealand, where he used horses he had worked with before. “We had a two-week grace period before filming started so we brought the horses halfway up the mountain where they could acclimatize to the cold weather and the altitude.”

A Journey in Time: Bringing Lost Worlds to Life

Throughout his career, Emmerich has pushed the envelope on what was possible with visual effects, creating such memorable big-screen images as the White House explosion in “Independence Day” and the giant wave in “The Day After Tomorrow.” Ongoing technological advances allowed Emmerich to unleash his imagination for the epic experience he sought to create for “10,000 BC.”

Emmerich enlisted visual effects supervisor Karen Goulekas, with whom he has collaborated on past films including “Godzilla” and “The Day After Tomorrow,” to oversee the film’s massive effects undertaking. “Karen is one of the most ingenious and visually inventive people I have ever worked with,” the director states. “To her, nothing is impossible. I know I can count on her to bring even my most ambitious concepts to the screen-often more spectacularly than even I first envisioned them.”

The most extensive work would involve the creation of the film’s menagerie of mighty, ancient creatures — mammoths, the saber-tooth tigers and terror birds. Emmerich wanted lifelike movement for these creatures and so looked to their modern-day relatives. “We used a lot of reference footage of elephants, of tigers, of ostriches,” he says. “The main issue was that no one knows exactly what a real mammoth moved like. They were a very distinct animal. You can only understand how an animal works from animal footage.”

The most challenging aspect of re-creating the immense Pleistocene epoch animals was their hair: long and matted in the case of the mammoths, feathered for the terror birds, and, in the case of the saber-tooth tiger, interacting with water. “We had to basically reinvent the wheel for hair behavior to make these animals photo-real,” comments Emmerich. “It’s a challenge to do it right, and we hired two companies in England to make sure these animals looked so real you could almost reach out and touch them.”

Goulekas joined the project two years before start of principal photography and began her work breaking down the script according to its effects needs, eventually translating each theme to concept art, maquettes (sculptures to be scanned into the computer) and models. Her focus was the three main set pieces of the film — the mammoth hunt, the terror birds sequence, and D’Leh’s encounters with the saber-toothed tiger.

Goulekas built a library of illustrations, photos and CG images from television shows as references for all the creatures in the film. She also visited the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, which provided a rich source of research on mammoths, as well as the Tala Game Reserve in Durban, South Africa, where she shot HD footage of a variety of wild animals, including lions, tigers, leopards, elephants and ostriches. The images she gathered enabled the animators to study the animal movements from different angles.

One of Goulekas’s most challenging projects was the film’s terror birds — flightless predators with huge beaks — which are based on creatures that existed in South America. “They were gigantic,” says Goulekas. “We know how fast an ostrich can run and how much damage it can do with its powerful feet, and combined that knowledge with the fact that there is a direct link between the terror birds and the dinosaurs. We based their look on a hybrid of different illustrations.”

Perfecting the movements of all the creatures required multiple passes at their design in close collaboration with Emmerich. “It’s a process of discovery,” Goulekas says. “You change it and change it until you get it right. This film was creative and collaborative and forever evolving. Roland gave me all the input I needed but also a lot of creative freedom.”

Once the designs of the creatures were finalized, her team of 18, including character animators and asset makers, then began pre-visualization (previs), an animated 3-D storyboard of all the effects sequences. “For example, for a scene in which D’Leh walks through the tiger gorge, we built a 3-D environment of the gorge and the artist then animated the tiger jumping down from a bird’s eye view of the scene, as a means of blocking the action,” describes Goulekas. “Then we put in some camera angles and, with our previs editor, Steve Pang, and the previs supervisors, we looked at all the cuts and discussed what needed to be done with the individual artists.”

The previs became an invaluable tool on-set for cast and crew alike. “I always showed the actors the previs before we set up a scene so they would know the big picture of what was going on around them,” comments Emmerich.

For director of photography Ueli Steiger, it also provided an invaluable aid to lighting. “Previs is a real guideline for how to shoot a particular scene,” he confirms. “Obviously it ends up looking different when it’s shot and there is a lot of improvising that goes on when you’re actually filming, but it’s a guide.”

Emmerich’s collaborative spirit enabled the artists on Goulekas’s team to set their imaginations loose, always in close interaction with her and the director. “We would discuss their suggestions and would often incorporate their ideas into the work,” she notes. “It resulted in a much higher quality of work. There’s a sense of ownership on behalf of the artists; they feel as though they’re part of the storytelling.”

During production, Goulekas and her team joined the actors and on-set crew armed with measuring sticks, flags and other objects painted blue, to eventually be replaced by moving digital creatures. “For the terror birds sequence, we had a blue terror bird head on the end of a stick, so that as we were framing up, we could visualize it,” she explains. “For the tiger sequence, we had a full size tiger mapped on a flag which we could just walk across the frame. If you don’t get the framing right, it’ll burn you later. With the height stick, the actor can see where he’s looking, and then the director can shoot whatever he wants.”

Interacting with visual effects props was an interesting exercise for the young actors in the film. “It’s a unique chance to really use your imagination,” comments Steven Strait. “It gives you a lot of room to play with because you’re not restricted by anything physical. During the shooting of the mammoth hunt, there was such an intense sense of freedom in interacting with something that doesn’t exist.”

Crossing Continents: Creating the World of “10,000 BC”

Emmerich collaborated with his behind-the-scenes creative teams to create a world for the film that would be primeval and harsh, and would also transport audiences to a time and place they had not experienced before. Though the film does not dictate a specific place, for Emmerich, it was always Africa. “It’s the cradle of mankind,” he notes. “But because of the story we wanted to tell, it became our own made-up Africa.” The film would be shot predominantly on practical locations encompassing New Zealand and multiple sites on the continent of Africa, including Cape Town, South Africa, and the moonlight vistas of Namibia.

The production was originally scheduled to shoot just a few days in New Zealand, but during a helicopter location scout just six weeks before the start of production, Emmerich was captivated by this proverbial “Eden.” “We had spent the morning doing our helicopter work and I was going back to the hotel when I got an emergency text saying, `Get back in the helicopters. Roland wants you to see something,'” recalls producer Wimer. “I was all ready with my speech to say, `We can’t change our location so close to the start date of the movie,’ and then I got up in the helicopter, and just as I came over this certain rise, there in front of me, laid out was the perfect location as the script had been written, as it had been envisioned in all the storyboards. And it was just so perfect that we had to shoot there.”

The icy white landscapes against the black rock formations of the untamed terrain provides a breathtaking contrast to deep greens of the South African tropical jungle that provided the backdrop to the middle section of the film and the burnt oranges and reds of the landscapes of Namibia, where the third act of the film was shot. These vistas made New Zealand impossible to resist, despite the fickle vagaries of the local weather, which forced the crew to negotiate fog, snowstorms and blizzards amidst the days of beautiful blue skies.

Wimer offers, “One of the things that we wanted to get across with the terrain is just how difficult our characters’ lives would have been in those times…but also how grand and spiritual and beautiful it all is. That is one of the reasons we had to shoot there: it was just so unreal and so extraordinarily magnificent.”

The pristine landscape was also protected, requiring the company to take great pains to leave as small a footprint as possible. “We used four-wheel drive access equipment, small buggies with light footprints, which we could drive across the turf without leaving tracks,” comments New Zealand location manager Jared Connon. “And we used the helicopter a lot to first fly in the props and sets for the mammoth hunters’ village and then fly them all out.”

Waiorau Snow Farm, situated some 5,000 feet above sea level on the South Island near the town of Wanaka (a site used for testing cars from around the world), provided five main locations for the film, including the mammoth hunters’ village, Baku’s Rock, the kill site and the grasslands. Approximately a third of the film was shot there. Other locations in New Zealand included Mount Aspring National Park and Poolburn Dam.

For Emmerich, Snow Farm provided the perfect backdrop for the film as he saw it in his head. “This is a landscape where you could go high up and turn the camera round and it would be like you were shooting the surface of the moon,” he raves. “It has an ancient pre-historic feel to it. Our characters travel during the film and we needed big vistas to convey the new worlds they enter. There had to be as much variety as possible.”

Prior to the start of principal photography, production asked the Ngai Tahu (the principal Maori tribe of the southern region) to visit the location to hold a traditional Maori blessing ceremony. “The land has an indigenous people that pre-dates the present population,” explains actor Cliff Curtis, who is of Maori descent. “So, evoking the notion of that spiritual relationship with the land is significant. And as a production, acknowledging that relationship felt right to all of us, particularly considering the film we were making.”

To create the Yagahl’s village, the filmmakers analyzed their lifestyle and the land that sustains them. “The mammoth hunters had limited materials,” says Emmerich. “They have the mammoth’s bones, tusks and skin, and used those to build their huts.

Because we’re imagining them as a spiritual people, I was keen that their dwellings would be unique and reflect their heightened creativity.”

For the mammoth hunters’ dwellings, production designer Jean-Vincent Puzos designed huts that used bones and skin in a visually striking and completely believable way. “The interior of Old Mother’s hut is made of 10,000 mammoth bones hanging from a mammoth skeleton,” he describes. “It’s the setting for the opening of the film when Old Mother is performing a ceremony and we wanted it to have a very cosmic feel.”

After extensive research, primarily in archaeological reference books, Puzos outlined 20 different mammoth skeletons. “The bones are just a little over-scale so that they give more visual impact on the big screen,” says Puzos. “We chose to decorate Old Mother’s hut with bones carved with tribal symbols and skulls to give a suitably spiritual atmosphere for the opening ceremony.”

Using wood as a substitute for actual bone, Puzos’s team of sculptors took a month to make the skeletons in the production base at Cape Town, South Africa, while another team created the mammoth furs and hides from local animal skins. The finished bones and hides were shipped out on a cargo plane to the New Zealand location at Wanaka, where the set took five weeks to assemble.

Wimer recalls, “We had rooms-full of people sanding mammoth bones made out of wood. They were formed in Cape Town, then taken apart and shipped to location. We actually had to convince the authorities they weren’t real mammoth bones,” he laughs. “It was quite an extraordinary logistical challenge, but in the end it all looked fantastic.”

When it came to decorating the rest of the village, the team improvised with a variety of different natural materials they found in New Zealand. “Farmers collected bones for us,” says set decorator Emelia Weavind, “and we found lots of wonderful seaweed that we used for the interior of Tic’Tic’s hut.”

One of the key props designed by Puzos was the White Spear, which chief hunter Tic’Tic must pass to his successor. The spear had to be practical but also visually arresting. The end result was a roughly six-foot spear with an intricately-carved removable ivory top piece.

Similar to the production design, costume designers Odile Dicks-Mireaux and Renee April sought to keep the costumes simple and appropriate to the people who wear them. Dicks-Mireaux began her research in the British Museum, as well as archive collections in Cape Town. However, she acknowledges, “There’s not much at all on clothing in the British Museum. The only visual records from around that era are some rock paintings in South Africa. So we took inspiration from the screenplay. We decided to color-code the different tribes: the mammoth hunters have very little color and are more integrated into their landscape. We came up with the idea of shaving springbok fur, which creates a lot of texture.”

The costume designers adapted the Yagahl costumes for the cold, harsh weather conditions in which they lived. “There would be no sandals,” says April. “They would have used fur in layers to keep warm, so we created heavy costumes made of antelope fur and hides doubling for mammoth fur.” With a nod to the weather, modern-day accoutrement supplemented the authentic costumes. “We also gave the actors thermals to wear because it was very cold on location,” April smiles.

The combination of wardrobe, hair, make-up and the locations made slipping into character easier for Strait. “Being on top of a mountain in New Zealand with dreadlocks down to your chest makes it a lot easier to pretend you’re a mammoth hunter,” he says. “The facial hair was mine but I wore a wig and they darkened my skin tone to look as though I’ve lived outdoors all my life. It was a bit of a process in the morning but the results were worth it.”

For the slave raiders, Dicks-Mireaux designed costumes that would appear outlandish and other-worldly to the more primitive mammoth hunters. “We used completely different colors from the brown and tan hues of the mammoth hunters’ costumes,” she says. “We have a lot of blues and reds in linens, jutes and wool. To emphasize the fact that they are a horse-riding tribe, we used horsetails to decorate their costumes. We also designed masks for them and a kind of early armor from chamois leather, based on ideas from African tribal references.”

Dicks-Mireaux also took her inspiration from contemporary African tribal cultures for the Naku, Hoda and River tribes that the mammoth hunters meet on their journey. “The Naku tribe is more colorful, and we also gave them clay bead necklaces to convey that they are more sophisticated than the mammoth hunters,” she says.

For the final scenes in which D’Leh comes face to face with the god and his priests, April designed wine-colored costumes informed by a variety of different cultures, including Tibetan and Egyptian. Their intricate jewelry and facial tattoos, designed by make-up artist Thomas Nellen, completed the look.

Wearing the costumes helped enrich the actors’ relationship with their characters. “Just putting on the wardrobe makes you feel like you are part of that world,” affirms Camilla Belle. “It helps you get into the character. You even move differently when you are in costume.”

Apart from the principal cast, the costume designers and their teams had the task of dressing almost 800 extras as slaves for the final scenes. Despite the numbers, “we couldn’t order the costumes,” April states. “And we couldn’t make them by machine; they all had to be handmade; otherwise, it would show. We had an army in the workshops making beads from clay and glass and sewing them on to the costumes as well as making the fabric and headdresses.”

There were six different tribes, all with their own particular styles, from their head to their feet. The team created over 1,000 sandals which had to all be made-to-order according to the sizes of the extras.

“We also had to make sure these costumes, like all the costumes, didn’t look new, so we had to distress the leather and fabrics to make them look worn,” April recalls. “This was a very ambitious movie, and working on location makes it even harder. But I found really wonderful crews in both South Africa and Namibia. And we worked with a lot of very skillful artisans, such as cobblers and hat makers, who really delivered what we wanted.”

From New Zealand, the cast and crew moved to Cape Town, South Africa, a country with a sophisticated cinema infrastructure, capable of accommodating almost as many film shoots annually as Los Angeles. There, a wheat farm location and Table Mountain Studios provided the interior of the Lost Valley, where D’Leh and his fellow hunters confront the vicious terror birds.

Table Mountain Studios and a wheat farm outside Cape Town provided the locations for the lush, primordial “Lost Valley” jungle setting. Cape Town location manager Katy Fife and her team spent three months building and planting grasses, trees and bushes on the wheat farm for the maze of tall grasses the massive creatures use for camouflage during their hunts. Also in Cape Town, the company shot at Thunder City, where the saber-tooth tiger trap pit was built in a large airplane hangar.

The final section of the film was shot on the sprawling deserts of southwest Namibia, including the pristine and historic Spitzkoppe, which Emmerich remarks, “was so perfect, with the sand dunes and the kinds of enchanting places you can only find in Namibia.” The filmmaker composited shots to form the bridge from the mountains to the desert, but in both instances, he was overwhelmed by the breathtaking natural beauty of the locations.

The site held special resonance for Emmerich for another reason. “Spitzkoppe is very close to my heart because it’s the place where Stanley Kubrick shot the background plates for the ape sequence in `2001: A Space Odyssey,'” he reveals. “It’s a magical place.”

Producer Wimer affirms, “One of the unusual things about Spitzkoppe is that it has this real resonance, this unusual energy that you find in certain places in the world. It’s difficult to quantify, but it does feel as though there is some sort of presence in the rocks.”

The filmmakers were given permission to use Spitzkoppe, with its unusual rock formations, for the scenes in which the Yagahl hunters meet the Naku tribe, and D’Leh begins to grasp the implications of his destiny. The Naku tribe is a well-developed savannah tribe with pastoral and farming habits and art director Robin Auld offers, “Their village is made of houses built on a rock shelf. The houses were either built around a four-sided frame or a round frame and the roofs were covered in adobe. It was quite a complicated process of construction.”

Spitzkoppe is a national monument on communal land, and all location fees went towards the local community. One hundred and thirty locals were employed during pre¬production to build access roads and game fences for the springbok and zebra brought in for the movie. Following filming, the animals were donated to the local community for its planned nature park.

With no hotel accommodation within easy access to the Spitzkoppe location, cast and crew camped out in a specially erected tented city, complete with warm water, TVs and internet access. During the shoot, 60,000 liters of fresh water were brought into the camp every day from a source over 70km away.

One of the mysteries of the movie is the identity of the lost civilization D’Leh finds in the desert. Kloser relates, “When our heroes come over the crest of a dune, they see this gigantic civilization-these `mountains of the gods,’ these mythic-sized pyramids, which are almost inconceivable to them. And part of the journey is understanding how this culture managed to enslave so many, and what it will take to challenge an empire like this.”

The pyramids were constructed at the desert location of Dune 7, near Swakopmund. Here, the production design team constructed a quarry, an enormous ramp and the façade of God’s palace. Having utilized helicopter shots to give a sense of scale to the characters’ journey, Emmerich sought to bring the same effect to some of the shots of the pyramids, and enlisted his effects team to create giant models of the pyramids which he could shoot using a Spydercam, a remote control-operated camera attached to wires.

The team erected the miniature replicas of the pyramids, the palace, the slave quarters and the Nile River close to the practical pyramids. Built on a scale of 1:24 in Munich and then transported to Namibia in fifteen sea containers, the set covered approximately 100 square meters. The Spydercam allowed the director to move freely through the miniature set, providing spectacular 360 degree aerial shots that harmonized with the film’s aerial sequences.

“The Spydercam makes the same kind of movements as a helicopter,” Emmerich comments. “It’s programmable, and goes in real time. The lighting situation matches the sets, and you have real sand dunes in the background. I’m very proud of this sequence because it combines old-fashioned models with super high technology in a great way.”

Marking his fifth collaboration with Emmerich, cinematographer Ueli Steiger relished the opportunity to work again with the director on such a provocative premise. “He’s a great collaborator and has a great vision,” says Steiger. “He works out most of what he wants before you join the project but he’s always willing and able to adapt. And he’s very open to suggestions from everyone.”

In keeping with the naturalistic style of the film, Steiger kept camera and lighting tricks to a minimum, opting instead for a classic style that would bring out the epic qualities of the story and take advantage of natural light. “We often used multiple cameras so we could make the most of the sun when it appeared,” he notes. “You have to work very fast. We would often rehearse for several hours and then shoot with three or four cameras and hope to get all the angles in one take.”

The final creative element of “10,000 BC” was the music. Wearing his third hat on the film, Harald Kloser teamed with fellow composer Thomas Wander to create the film’s score. The composers worked closely with Emmerich to capture the action and emotions musically within the context of the film’s unique setting.

The director notes, “The story is a classic hero myth, and the music followed that. But it also has a lot of ethnic elements, a lot of big horns, vocals and drums. One of the things I like the most about making movies is to see how the music matches your images. There’s this magic moment when you first record a piece with the orchestra, and it’s just right.”

For Emmerich, the final mix of all the creative components is the ultimate payoff for the long, often arduous process leading up to it. “I have incredible fun making movies because they’re so intricate. There are so many facets to them, and I love to have my head busy with all these different issues, always trying to invent new ways of looking at something. But even with all the technical aspects, at the very end it comes down to character, because the most elaborate sequence doesn’t work unless you care about who it’s happening to.”

Through the extraordinary journey of one young man, the adventure of “10,000 BC” delves into many different themes, including the nature of heroism and leadership and the power of human connection. “Every man has to decide how big the circle is that he belongs to,” says Emmerich. “Is it just his loved ones, his family, or is it maybe a much wider group of people? Our hero has to go on a journey of discovery. He has to mature from being a selfish young boy to become a leader of men. And the key is how wide the circle is…how many people you embrace in the circle.”

Production notes provided by Warner Bros. Pictures

10,000 B.C.

Starring: Steven Strait, Camilla Belle, Cliff Curtis, Omar Shariff, Reece Ritchie, Suri van Sorsnsen, Tim Barlow, Marco Khan

Directed by: Roland Emmerich

Screenplay by: Roland Emmerich, Harald Kloser

Release Date: March 7th, 2008

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for sequences of intense action and violence.

Studio: Warner Bros. Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $94,784,201 (35.2%)

Foreign:$174,288,569 (64.8%)

Total: $269,072,770 (Worldwide)