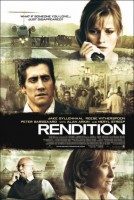

Tagline: What if someone you love… just dissapeared?

Isabella El-Ibrahimi (Reese Witherspoon), the wife of an Egyptian engineer, tries desperately to track down her husband after he disappears on an international flight. Meanwhile, a CIA analyst’s (Jake Gyllenhaal) world spins out of control as he witnesses the engineer’s unorthodox interrogation at the hands of secret police.

Jake Gyllenhaal, Reese Witherspoon, Alan Arkin, Peter Sarsgaard and Meryl Streep head an all-star ensemble cast in Rendition, a compelling thriller from director Gavin Hood (director of the Academy Award-winning film, Tsotsi) which takes a provocative look at the complex political issues surrounding the U.S. government’s policy of “extraordinary rendition” – abducting foreign nationals deemed a threat to national security for detention and interrogation in secret overseas prisons.

Rendition boldly explores the gray area between left and right and right and wrong and finds no easy answers. Director Gavin Hood, whose film Tsotsi became the first film from South Africa to win an Academy Award, makes his American motion picture debut directing screenwriter Kelley Sane’s multi-layered story. Rendition was filmed in Los Angeles and Washington DC, Marrakech, Morocco and Cape Town, South Africa.

About the Production

Screenwriter Kelley Sane first decided to write Rendition after a lively debate with his friend, Mark Martin, about the American government’s little-known policy of “extraordinary rendition,” which allows for the abduction of foreign nationals, deemed to be a threat to national security, for detention and interrogation in secret overseas prisons.

Sane remembers, “Mark Martin, who is a co-producer on the movie, and I were talking about the potential for abuse, and how it seemed to not follow the lines of the American ideal. Mark suggested that I write a script. I had to think about it because watching someone getting picked up and tortured doesn’t necessarily seem that cinematically interesting. On deeper thought, what really struck me was the fact that if someone disappeared, their family would have no idea what happened. Thousands of people disappear in this country every year, for various reasons, and I could imagine the heartache of not knowing where a loved one is”

Producer Steve Golin first saw the script in its early stages. “David Kanter and Keith Redman, who work with me at Anonymous Content, had found the script along with Mark Martin, who was working with my company at the time,” says Golin. “We worked on it for about a year. It really was a team effort. The thing that impressed me about the script was that it avoided being too preachy and that it really tried to explore “extraordinary rendition” and what the effects are on the individual people.

“I think it basically shows two sides to the story,” adds Golin. “I think a large majority of us are willing to accept that if there is imminent danger that will affect the lives of thousands of people, one likely way to get information out of someone who holds it is through forcible coercion. On the other hand, the United States government has, over its history, in cases of war and emergencies, abandoned civil liberties. I think by exploring this issue we are letting it be known that there is a reason for the Geneva Convention and that there are laws to uphold, because, in the long run, that’s what makes society work. And I think by abandoning those things we are going down a dark path.”

When it came time to look for a director, Golin immediately thought of Gavin Hood, who won an Oscar for Best Foreign Film for directing 2005’s Tsotsi, a compelling drama which traces six days in the life of a ruthless young gang leader in the Johannesburg township of Soweto who ends up caring for a baby accidentally kidnapped during a car-jacking.

“Gavin is from South Africa, so he has dealt with a lot of very interesting political situations,” says Golin. “He’s grown up in a political environment, more so than a lot of Americans. I thought he would be very sensitive to the material. He has had friends taken away who disappeared without a trace. I thought this material would be something he would have an affinity for and connect with.”

Hood happened to be looking for a special piece of material for his follow-up to Tsotsi and his move into American filmmaking. “When I am looking for a project I really believe a great film does two things,” says Hood. “First of all it entertains you and keeps you excited and thrilled to be in your seat. But I also believe great films leave you with something to talk about afterwards. These are the films where you go out afterwards and have a really good discussion, debate, even an argument with your friends or your partner. That was what was so great about reading the screenplay for Rendition. It was a real page-turner and a good thriller that had me wondering `what’s going to happen next?’ But at the same time it was raising profound and difficult questions that don’t have easy answers. I remember finishing the script and just sitting for days wondering `what do I think about this?'”

Producer Bill Todman, Jr. was happy to have Hood on board as director, “Gavin brings an innate ability to tell a story without having to use any devices. Tsotsi was all subtitled. And you could literally turn off the volume and follow the story. He was a natural choice as a director, as he has this ability to weave all these intricate stories together.”

One of the first challenges facing the filmmakers was in tackling the script’s multi-layered storylines. Hood explains, “You have to keep everything in balance and let every storyline arc sufficiently because essentially you are making four or five short films and weaving them together. One of the challenges I found exciting was how to get the maximum emotional impact, the maximum plot and story impact in the least amount of time so that you keep your audience moving. That is a tremendous challenge from a storytelling point of view and very exciting because there is no room for fat.”

Jake Gyllenhaal, who portrays CIA analyst Douglas Freeman, adds, “This production was unlike any other I’ve worked on. The Morocco shoot felt like its own separate movie, when in actuality it was just a small piece of a larger picture. I think when we finally see the film it will be exhilarating to see how Gavin has woven the different pieces together.”

Hood and screenwriter Kelley Sane teamed up for further work on the script prior to the start of production. “When I initially read Kelley’s script, I thought it was structurally brilliant. He has this tremendous twist that happens at the end of the film that really catches you by surprise. All the characters are beautifully drawn in terms of coming from different angles of the story. So my work with Kelley was not about trying to create the story, since he’d already done that beautifully. It was a matter of finding rhythm and pace, which is a director’s job, and to find the emotional arcs of these stories and whether we were in balance within the story. And, then, of course, to ask about the balance from almost a legal point of view. Are we making the argument for the necessity for torture and the other argument against torture? Are these arguments balanced in the film? Because the one thing Kelley and I didn’t want to do was to tell the audience what to think.”

With screenplay in hand, the filmmakers set out to find the ensemble cast that would bring these characters to life, ultimately bringing together some of the screen’s most accomplished actors.

For the role of Isabella El-Ibrahimi, whose must seek answers to her husband’s unexplained disappearance, the filmmakers pursued Reese Witherspoon, who won an Academy Award for her role as June Carter Cash in 2006’s Walk the Line.

“Obviously Reese is a real all-American girl next door,” says producer Steve Golin. “I think she is someone everyone can relate to…if this scenario can happen to Reese, it can happen to anyone.”

For her part, Witherspoon was instantly attracted to the material. “I liked the idea that the different story lines all lead to similar situations, but not in the way we have seen in other recent films that have multiple interwoven stories. The interesting element to me was that each person’s story is about isolation. It isn’t about connection. It’s about how we are singular in the world.”

“I was also drawn to the role of Isabella because I have a lot of curiosity about what it must be like to be living as part of a Muslim family in America. We have a lot of ideas about certain religions, and a lot of fear has been propagated. I was interested in dispelling some of that fear.”

“Reese is incredibly disciplined and is always completely prepared,” says director Gavin Hood. “She knows exactly where she is going. The only thing that was difficult for us was that it was my first experience working with an actress of her caliber and her fame — so I’d never before experienced the sight of the paparazzi all over the place!”

Witherspoon researched her role by meeting with Muslim Americans. “I also found communities on the internet and read books,” she adds. “It’s fascinating to me that in this country we have so many different kinds of people and as many different religions. It’s part of the real beauty of America that people are allowed to practice religion without prejudice. But, then again, since 9/11, it has clearly been a more difficult situation for some families.”

Jake Gyllenhaal, an Oscar nominee for his role in Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, signed on to portray CIA analyst Douglas Freeman. “Jake plays a young man whose sense of right and wrong turns upside down when he finds himself thrown into an extraordinary situation,” says producer Steve Golin.

Gavin Hood adds, “Jake had a very difficult role because Douglas in a way is the moral compass to the film. He’s an observer, much like the audience. He is the one character whose opinion on the question of rendition is ambivalent. You don’t know which way he is going to go or quite what he’s feeling as the events of the film unfold around him. Jake did a brilliant job of knowing that his role as an actor was to say and do very little, yet absorb and emotionally reflect a great deal.”

Gyllenhaal was attracted to a role that was so different from anything he’d previously done. “Douglas gets to be in the middle of the action, both emotionally and physically, with no real outlet — and I found that kind of tension very exciting as an actor,” he says. “I think many people in my generation are searching for something – their identity, who they are, what they want to do with their lives. This is where Douglas finds himself. When we first meet Douglas he has resigned himself to a sort of apathy, but he is quickly faced with a haunting reality that shakes him and forces him to face his own humanity. It makes him look into himself and find that thing he was searching for. At the end of the movie, he finds himself where he least expected it-which is ultimately tremendously rewarding for him and also for me as an actor.”

Actor Omar Metwally joined the cast to portray the key role of Anwar El-Ibrahimi, who is suspected of being a terrorist, abducted and taken to a secret overseas prison. “Omar is a highly intelligent, very emotionally in-tune young actor,” says Gavin Hood. “He had a role that in many ways was tougher than some of the other actors because he spent a lot of time in scenes by himself. I’m very fortunate to have an actor of Omar’s ability in the role.”

“There are several scenes where Anwar is alone,” says Metwally. “I think those scenes are very important because torture is an isolating experience. It was one of the things that drew me to this character. It’s such an incredible role, it’s one that I think actors dream about playing because he is a man who’s just pushed to or is experiencing the outer edge of human existence.”

Two-time Academy Award®-winner Meryl Streep portrays Corrine Whitman, head of counter terrorism for the CIA. Gavin Hood relished the opportunity to work with the legendary actress.

“Possibly the greatest privilege on this movie was to work with Meryl, and I know it sounds sort of sycophantic to say, but it is true,” he says. “She is an icon and I can only say she is a consummate professional and so kind to everyone and completely disciplined. When you are ready, she is ready.”

Reese Witherspoon adds, “Working with Meryl — Wow! I’ve been lucky enough to meet her socially, so I knew she was a doll. She is honestly the nicest person, so lovely and gifted, but also a wonderful mother and completely down to earth.”

Rounding out the international cast are American born Peter Sarsgaard and Alan Arkin (a recent Oscar winner for Little Miss Sunshine); Israeli actor Igal Naor; Moroccan actress Zineb Oukach; and Algerian actor Moa Khouas.

The topic of “extraordinary rendition” was a daily topic of discussion on the set — from the actors to the filmmakers to the international crew. It remained a hot button issue that fueled a lot of differing opinions.

“My reaction when I first learned of `extraordinary rendition’ was pretty much disbelief that it was happening,” says Reese Witherspoon. It just doesn’t seem altogether American, to detain people without due process, and without the opportunity to be charged with a crime and to go through a proper trial. And that there is no legal recourse for people who have endured this type of torture is shocking. I am really proud to be part of a project that is bringing this practice to the public’s attention.”

“At the same time,” Witherspoon adds, “it’s a very complicated issue. I’m an actor. I can’t even imagine what it would be like to have the responsibility for maintaining national security. There are always two sides of every coin, and I hope this movie shows both sides of this issue.”

“I think one of the dilemmas for us in the West, and in particular here in America, is we find torture unpalatable,” says Gavin Hood. “We don’t do that. But the attitude is, `hey, if it’s gotta be done, just don’t tell me about it.’ And that’s where you get the concept of outsourcing the torture…’well, these countries do it anyway, so let them do it.’ That’s a moral cop-out. Just because you are removed from it doesn’t mean you are not involved. The other question is, does torture work? It’s apparent to enormous numbers of military lawyers, FBI agents, CIA agents…not just myself. It’s apparent to a great number of people actually involved in the process that it frequently results in poor intelligence. The information you get is often bad because the person you are getting it from is terrified and wants whatever you are doing to them to stop. They will say what you want to hear so you will stop torturing them.”

Executive producer Bill Todman, Jr. feels that “If a person is rendered and our government let’s that person go and they go to New York and blow up another building, is that right or wrong? If a government renders somebody and treats them and interrogates them in ways we would never do in the United States, and they are innocent… is that right or wrong? I am not sure if I have a firm perspective about it”

“In terms of survival of this country, and fighting for everything that we started out with, I do think the way we deal with things will have to change somewhat,” says Peter Sarsgaard. “It’s just by how much. And if by compromising what we do, do we become a country that we don’t want to be? Is it important to sacrifice one man for the benefit of 7,000. I think it `s wrong but it is a compelling argument. Rendition is something that our government could decide not to do anymore. But even if rendition goes away, there will be something else, some other way. We will be living with this for a long time.”

Igal Naor says, “I’m living in a country, Israel, which is talking and arguing about this question all the time because we are in a kind of war, and we have to do things that normally you can’t go on living after them. I was a soldier, my son was a soldier and my daughters are soldiers. And, well, I can say this — when you have to defend your life, or when you are in charge of the lives of innocent citizens, then sometimes you have to do things which are not so nice and not so human. This is a big question and I don’t know if I really have an answer. I know I resist many answers I see in the world, as with the idea of rendition and more than a few things that are done in my country. Everyone has to check himself and determine how human they can stay when forced to defend themselves, or their family, or their country cruelly.”

One of the key challenges for the filmmakers during pre-production was finding the ideal director of photography, one who was both technically brilliant and able to collaborate with Gavin Hood in visually piecing together a complex number of storylines. The filmmakers found that combination in Academy Award® winner Dion Beebe.

“When I met with Dion Beebe I was immediately convinced that I’d found a great collaborator,” says Hood. “Apart from the fact that he is completely unflappable, he has a superb eye and a deep understanding of story above all else.”

Producer Bill Todman, Jr. agrees, “Dion is the best D.P working today. He is this incredibly calm, easygoing but organized person. His work has such intensity and his ability to light and tell a story is amazing.

Once aboard the project, Beebe found his collaboration with Gavin Hood instantly gratifying. “We had a very accelerated period of pre-production — six weeks at the most. We were forced to find common ground quickly, to find that language as filmmakers. It has been a lot of fun. Gavin is a very passionate and talented filmmaker and it was great to collaborate with him.”

Early on, Hood and Beebe had to decide how they would differentiate the world of Washington, DC from the world of North Africa. Hood explains, “I have a background in still photography and I tend to favor well-composed and somewhat static shots, so I can be a little hesitant of camera movement. Dion was tremendously helpful in freeing me of this fear, while at the same time understanding my need at times to just be still and allow the audience to watch an actor closely.”

Beebe adds, “We didn’t want to get tricky with different styles because we constantly intercut. So the difference tends more towards how we compose, how we employ movement in the camera.”

Hood agrees, “Washington DC is seen as this rather formal world that is classically composed, structurally quite static in many ways. Vertical and horizontal lines. The Moroccan locations are full of arches and curves which allowed us organically to be much more fluid and chaotic.”

Beebe concurs, “In Morocco, there are these particles in the air wherever you go, there is a feel, you feel more light shafting through windows, so we really embraced that. Washington, DC is cleaner, a bit cooler, it is a bit more composed, the camera becomes more static.”

When initially scouting Washington, DC, the filmmakers thought it looked too conventional. Beebe initially wanted to hide all the monuments in the shots. Hood recalls, “We started driving around and looking at monuments from positions where you couldn’t actually see them and then we went into one building and saw the Capitol Building through a glass window, a modern building with a glass façade, vertical columns and glass plates. It had this sense of old Washington with its values that stood up for so long and a new Washington trying to impose itself on the old.”

Another challenge for the filmmakers was to find a location to film the scenes that take place in a third world country. The country, undisclosed in the film, could have been anywhere in the Middle East or North Africa. In this post 9-11 world, finding locations in that part of the world is a tall order. One of the safest countries for an American film shoot is Morocco.

“When I read the script, I knew we would end up shooting it in Morocco,” says producer Steve Golin. “Two years ago, we shot Babel in Morocco, and it’s a very film friendly environment. The King and Royal family are fantastically supportive of filming here.”

Gavin Hood agrees, “One of the other reasons for shooting in Morocco, apart from its visceral energy, is that it has a tremendously long history of making films. So the film crews and the people that work in film are extremely knowledgeable.”

The city of Marrakech in Morocco provided not only a safe filming locale, but also a distinct visual look. “When we scouted Marrakech I was amazed, just in terms of its color palette, its energy, this ancient city with these wonderful alleys. You can plant your camera almost anywhere and get a great shot. It’s just cinematically a dream,” says Hood.

Morocco also has a long history of beautiful artisan work, from rugs to lamps, mosaic tiles to ceramics.

Hood explains, “I think the Moroccan lifestyle and certainly in Marrakech, is very tactile and people make things. They do metal work and wood work, so that the people who work on the film, whether it be in set construction or props, wardrobe or the A.D department, they all have an artisan’s sense, they understand a beautifully visual world.”

Shooting in Morocco was not without it’s challenges, as executive producer Marcus Viscidi explains. “First of all, getting to Marrakech from L.A. takes about 18 hours. So if you want anything, you have to make sure you have it before you leave. Any film that involves weapons, special effects or pyrotechnics, you have to get that material in way ahead of time. It all has to be checked through customs and in this post 9/11 world getting weapons anywhere in the world is difficult, but getting them into countries in the Middle East or Africa is even more difficult. In Morocco, you have to plan months ahead and get approval from the King. You have to have a list and not vary from that list. So, if you decide at the last minute that you really need 50 guns instead of 40, you are not going to get those 10 extra guns.”

Filming on location in Morocco also involved shooting with not only an American and Moroccan crew, but truly an international crew. Rendition employed crew members from countries as diverse an South Africa, Great Britain, Italy, Israel, Egypt, Algeria, Australia and Sudan.

“I think it is wonderful when you walk on the set and you have South Africans, and Moroccans, Americans and Brits,” says Jake Gyllenhaal. “There is a real open heart here. I think that comes from Gavin Hood. I think every set Ive been on is defined by the director.”

“Shooting in Morocco with an international cast and crew was an amazing experience,” adds cast member Igal Naor. “For me, as an Israeli, to feel free, and to feel comfortable, to not be afraid of anyone or anything…I felt as if I was in London or Paris. It was great. I met so many Muslims who became good friends and after two weeks, we said to ourselves, `How can we be together? How can we have fun?’ Look how close we are. Judiaism and Islam are so much the same. And it’s is something that makes me very happy. I have many Arab and Palestinian friends in Israel, too. Why can’t it always be like that?”

Gavin Hood adds, “One of the fun things about this movie was the fact that we had crew made up from people all over the world working on a film that is essentially about the struggle of different cultures in this very stressful modern time. The debates among the crew members about the issues at hand were wonderful because I watched people grow and come to understand each other and enjoy being with each other. I hope this film reminds us that we are all just people with emotional issues and needs. I get so frustrated the way people want to talk about how people are different, yet we don’t talk enough about the ways in which we are the same.”

Production notes provided by New Line Cinema.

Rendition

Starring: Reese Witherspoon, Jake Gyllenhaal, Meryl Streep, Alan Arkin, Peter Sarsgaard, Christian Martin

Directed by: Gavin Hood

Screenplay by: Kelley Sane

Release Date: October 19, 2007

MPAA Rating: R for torture / violence and language.

Studio: New Line Cinema

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $9,736,045 (36.6%)

Foreign: $16,898,910 (63.4%)

Total: $26,634,955 (Worldwide)