Based one on of the most acclaimed novels in recent memory, The Kite Runner is a profoundly emotional tale of friendship, family, devastating mistakes and redeeming love.

In a divided country on the verge of war, two childhood friends, Amir and Hassan, are about to be torn apart forever. It’s a glorious afternoon in Kabul and the skies are bursting with the exhilarating joy of a kite-fighting tournament. But in the aftermath of the day’s victory, one boy’s fearful act of betrayal will mark their lives forever and set in motion an epic quest for redemption.

Now, after 20 years of living in America, Amir returns to a perilous Afghanistan under the Taliban’s iron-fisted rule to face the secrets that still haunt him and take one last daring chance to set things right.

The Story Behind ‘The Kite Runner’

In 2003, Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner came out of nowhere as a debut novel and quickly shot to the top of best-seller lists around the globe, where it still remains four years later. A story suffused with the culture of Afghanistan — the remote, war-torn country that, for decades, has been seen only as hotspot of global conflict — it seemed an unlikely candidate for such stratospheric success. Yet, with its universal themes of family bonds, childhood friendship, the courage of forgiveness and the salvation only to be found in love, the story deeply touched people from every cultural and social background.

Written by a physician born in Afghanistan — who, like his lead character, left Afghanistan for America as a boy and didn’t return for decades — The Kite Runner took readers on a journey, across continents, into one man’s quest to right a terrible wrong that haunted him all his life. Deftly weaving the personal with the political, Hosseini forged a tale as rife with suspense as it was with intensity of feeling.

Though the story was fictional, Hosseini’s intimate knowledge of growing up in Kabul when it was “the pearl of Central Asia,” before the Soviet Invasion and the rise of the Taliban, as well as his experiences emigrating as a young man to America, lent his story an authenticity and humanity that deeply affected readers. The novel sold over eight million copies in more than 34 countries, leaping borders with the power of its storytelling.

For Khaled Hosseini, the ripple effect of The Kite Runner’s popularity and now the imminent release of the motion picture based on it, have been extremely gratifying. “I’m continually astonished by how people have reacted to my novel,” says Hosseini, “but I think it must be because there is a very intense emotional core to this story that people connect with. The themes — of guilt, friendship, forgiveness, loss, the desire for atonement and to be better than who you think you are – are not Afghan themes but very human experiences, regardless of one’s ethnic, cultural or religious background.”

It was these themes, long before the book had attained international best-seller status – in fact when it was merely an obscure and as-yet-unpublished manuscript – that drew the attention of producers William Horberg and Rebecca Yeldham, who were previously partnered at DreamWorks SKG. While reading Hosseini’s unadorned pages, Horberg and Yeldham realized they were in the midst of something quite extraordinary. “It was one of the most powerful and cinematic pieces of literature that I had ever read. It was magical,” says Yeldham. “We were so in love with it that we couldn’t imagine it not getting made. It’s a story that’s told in the most lyrical, evocative and beautiful way, one that lends itself to a visual interpretation; as you’re reading, you literally see its events unfold.”

Adds Horberg: “Reading The Kite Runner was a wonderful experience. The story has such a strong emotional hook with its central idea that, no matter what you’ve done in the past, there’s a way to be good again. It draws you in as a reader and taps into the secrets and scars that we all have in our history. You go on a journey with these two boys, a journey into a culture, into a family and into redemption for the character of Amir. I found it to be an incredibly moving experience and one that promised a lot of potential as a movie.”

Horberg and Yeldham brought the Kite Runner to the attention of Walter Parkes and Laurie MacDonald, who were then beginning their transition from co-heads of production at DreamWorks to independent producers. The filmmakers joined forces to secure the rights to the forthcoming novel and development on the screenplay was begun. For Parkes, the heart of the book lay in the mysterious, albeit fragile, bonds of childhood friendships that are same the whole world over. “I thought right away of my relationship with my best friend when I was 10 or 11 and the kind of private, extended fantasy world young boys occupy in their friendships,” reflects Parkes. MacDonald adds, “It is very much about the resiliency of children. There is something about a child’s ability to find friendship and adventure in his own private universe with other children, which is so true and so heartbreaking and ultimately gives us hope. And that is the core value that spoke to me in the book.”

Meanwhile, the filmmakers enlisted Khaled Hosseini himself as an active partner in transforming the novel into a film, making sure he remained on the inside of the entire creative process. “Khaled was our ambassador into this world which none of us were from,” explains Horberg. With the film in mid-development, Horberg and Yeldham left DreamWorks in 2005. Horberg joined Sidney Kimmel Entertainment (SKE), which has a reputation for working with esteemed filmmaking talent and high quality stories, and Sidney Kimmel, in turn, became an enthusiastic supporter of the project and Horberg’s ongoing roles as producer of the film. Jeff Skoll of Participant Productions was another early and passionate fan of the book, and now joined with SKE as co-financiers.

In the midst of all this, the book burst onto bookstore shelves with an unexpected force, turning the novel into a cultural phenomenon, as it spread like wildfire from the hands of one exhilarated reader to the next. Critics were equally impressed. As award-winning writer Isabel Allende summarized of the novel: “It is so powerful that for a long time everything I read after seemed bland.” The filmmakers were at once astonished and thrilled at its sweeping popularity.

“Truthfully I don’t think any of us had any suspicion that The Kite Runner would catch on in such a mainstream way,” confesses Parkes. “It was a great story that had a heroic, cinematic size to it and dealt with essential themes of redemption and coming to grips with who you really are — wonderful, classic themes. But to assume that it would become a hit book and then some, and that years later, the environment of American mainstream film would become so open to these kinds of multicultural stories? Nobody could predict that.”

Adapting The Kite Runner

Now, with the book having worked its way into the hearts of so many, the producers set out to find a screenwriter who could take the rarely seen world Khaled Hosseini had brought so richly to life on the page and transform that into an epic, cinematic experience, all the while sustaining the uniquely intimate tone of the book.

Horberg and Yeldham brought in screenwriter David Benioff who, as a novelist himself (Benioff made his screenwriting debut with the adaptation of his novel THE 25TH HOUR, directed by Spike Lee), came into the project filled with original ideas about how to morph the 400-page novel into a taut, riveting script and structure it in a vivid new form.

“Everyone was very open to different ideas and angles, but the one commonality we all shared was a desire to do justice to Khaled’s beautiful story and to try to retain as much of the book’s humanity and spirit as possible,” says Benioff. “I always saw this as a story about cowardice and courage, and the journey between them. And also I wanted to make sure it remained a story of Afghanistan, of Afghans, of a people enduring the worst possible times, endless wars and poverty — yet within that national horror, still finding the possibility of grace, beauty and love.”

Benioff utilized Hosseini in myriad ways while creating the adaptation. “Khaled could not have been more generous with his time and expertise, answering all my questions about life in Afghanistan,” he comments. “I grew up in New York City and a Kabul childhood was very far from my own experience, yet Khaled clarified any moments I found confusing. More than that, these characters are his babies and Khaled knows them better than anyone, so he was always very good at explaining why a character would or would not do something.”

One of the biggest challenges for Benioff was simply carving the sweeping, three-decade-long events of Amir’s story into a two-hour motion picture. “Time jumps are difficult to navigate in a movie,” explains Benioff, “and because the novel covers almost 30 years, figuring out an efficient screenplay structure wasn’t easy. The novel shows Amir at many different ages, but I decided early on that I wanted only two actors playing the role. Any more than that and I think you might lose the connection to this wonderful character. So the screenplay streamlines the novel’s narrative – it incorporates almost all of the major beats but simplifies the chronology. Luckily, the heart of Khaled’s story is so strong I believe it maintains its power even within restrictions of space of the screenplay format.”

Khaled Hosseini was ultimately very impressed with how the screenwriter re-invented his story as a cinematic experience. “My hat is off to David,” says Hosseini. “He had a job cut out for him. This is a novel that structurally is a challenge, spanning 30 years in time. There are flashbacks, the characters age, and we move from Kabul as a thriving cosmopolitan city to this basically destroyed landscape that Amir goes back to. But David pulled it off and made it seem very seamless so that when I read the final version of the script, I said `This is going to be a beautiful movie.’”

Now came the task of finding a director. The producers knew they needed someone with both the cultural sensitivity and the far-reaching imagination to wrap his mind around a story that traverses from Kabul to California, from the shame and devastation of war to the opportunities of starting over in America, from the stultifying effects of violence and intolerance to the triumph of honor and hope. They chose Marc Forster, largely because he has brought a lyricism and humanity to every film he has made, no matter the genre, ranging from the powerful emotions of MONSTER’S BALL to the enchantment of FINDING NEVERLAND to the inventive comedy of STRANGER THAN FICTION. He had also worked with David Benioff before, on the time-shifting psychological thriller STAY.

“Marc was someone whose work we admired greatly,” says William Horberg. “Whatever world he goes into, he always finds characters that audiences understand and relate to deeply. He has a real sense of both beauty and curiosity in his filmmaking. And, because this story was so different than anything he had done before, we felt it would also be a compelling challenge for him.”

It quickly became clear that Forster had the deep affinity for the material the producers were seeking. “In his fearless way, Marc had no qualms about making a movie about a culture that is not his own,” notes Rebecca Yeldham. “He embraced obstacles that would have unhinged others. And he was able to cut straight to the heart of the story and the reasons why it touched him and so many millions of people.”

For Forster, the story of Amir and Hassan’s idyllic childhood friendship and the dramatic turn of events that would come to shadow Amir’s brand new life in America, was irresistible. “I just fell in love with this story,” the director says. “Reading the book was such an emotional and beautiful experience that I knew right away I wanted to be involved. Like MONSTER’S BALL, yet in a very different way, it is a story about breaking the cycle of violence and about the sustaining possibilities for redemption. For me, the challenge would be creating this incredibly epic journey while bringing the audience inside a very intimate story about a few individuals and the profound effect they have on each other’s lives. That mix is the real beauty of the novel.”

Yet, even Forster was not prepared for how intense an experience making this film would ultimately be, taking him from Europe to Kabul to Pakistan and China on an eye-opening and, at times harrowing, journey that would, in all of its own imagery and emotion, come to inform every frame of the film.

From the beginning, Forster understood that in order to bring the film to life he must penetrate the dense and complex fabric of Afghan culture and experience. As he began preparing the project, he shared his vision of the film with Khaled Hosseini, which helped to forge a great kinship.

“I was very happy to hear that Marc would do everything in his power to make this movie as authentic as possible from a cultural standpoint and that Marc really wanted to show something to the audience that had never been seen before,” says Hosseini. “He spoke to me with such passion, integrity and honesty about the book, and he told me how fearful he was of not doing justice to it and me. But I was not worried because I saw how enamored he was with the story, how completely invested in it he was and, watching him on the set, I saw how talented he is.”

Says Forster, “David was masterfully able to capture the spirit of THE KITE RUNNER in his adaptation. The main thing was always not to let Khaled down because ultimately it is his vision and, as a director, I wanted to serve the vision of the original author who touched so many people.”

From English To Dari

While David Benioff was still writing the screenplay, a decision was made to shoot the film in the Dari language, one of two main tongues spoken in Afghanistan. “I felt that shooting the film in any other language other than Dari would be a mistake,” says Marc Forster. “If you have kids in 1970s Afghanistan speaking English, it just would not be right. You need that emotional connection to something real.”

The decision, though logistically daunting, was celebrated by author Khaled Hosseini. “When Marc said he was going to shoot the film in Dari, it won me over and I said he really means to do well by my book, because it was so important for me that the characters be believable,” he says.

Benioff and Forster had extensive discussions about which lines in the film should be spoken in Dari and which in English. Then, when the intricate translations of Benioff’s screenplay were completed, they sent the script back to Khaled Hosseini, who lent his own poetic ear to the tweaking of various lines and the adding of various phrases that add the more natural and realistic feeling of a native speaker. The result was a screenplay that is, according to Hosseini, “credible and beautiful Dari.” (There are also a few lines in Pashto, a language spoken by the Taliban, and the Pakistani language, Urdu.)

To keep the language faithful to the material once production began, the filmmakers hired a team of native Dari speakers who coached the non-native actors on pronunciation and inflection, and were on set each day to make sure lines were spoken just as they would be in Kabul. On-the-fly translations on the set were handled by Ilham Hosseini, a UC Berkeley Law School student who escaped with her family from Afghanistan – and is also the younger cousin of Khaled Hosseini.

In addition to the native Dari-speaking language and dialect coaches, the production hired several cultural advisors who were on hand throughout the filming to validate the most nuanced details of the film’s production. Scores of researchers were also consulted throughout the filmmaking process to ensure the verisimilitude of the film’s content and representations.

From London To Kabul

Marc Forster was determined to cast the book’s beloved characters with as much realism and integrity as possible under the unique circumstances. This was especially true when it came to casting young Amir and Hassan – the two boys, one privileged, the other from the servant classes, whose friendship is torn asunder in a catastrophic instant, setting in motion Amir’s perilous search for redemption as a grown man. Forster knew he needed two extraordinary young actors who could truly understand Amir and Hassan’s cultural background, yet who would also have the skills to breathe raw life into their boyish dreams and camaraderie and draw the audience into their innocent world of kites and fairy tales and sling-shot heroics.

To find this daunting mix of qualities somewhere on earth, Forster recruited Kate Dowd, the London-based casting agent who previously had worked with the director casting FINDING NEVERLAND. Dowd is known for her deft instincts but THE KITE RUNNER would see her heading off on one of the most epic casting quests yet, one that would span several continents and eventually lead all the way to the war-torn streets of Kabul, Afghanistan. “Kate found the remarkable children in FINDING NEVERLAND,” says Forster, “and I knew she would bring that same sensitivity in finding the young boys for THE KITE RUNNER – but I didn’t yet realize it would mean going to Kabul.”

The filmmakers placed their faith in Dowd’s ability to find hidden talents in very young, inexperienced children. Explains William Horberg, “We knew that THE KITE RUNNER as a movie experience was going to hang on finding the purity of the two boys that Khaled describes in the book – two boys who could embody that sense of class tension that they have, the ethnic differences between them, but also the chemistry of brotherhood that they have. We knew it would be like catching lightning in a bottle.”

Dowd’s hunt for that lightening began in the Afghan communities of Europe, the U.S. and Canada, and extensive open calls in London, Birmingham, Hamburg, Amsterdam, Toronto, New York, San Francisco and Virginia. But, despite the hundreds of children of Afghan background they saw, the filmmakers continued to feel something was missing. While many of the boys who auditioned could speak some Dari, their speech was already inflected with the regional accents of wherever they lived. “Out came the accents of England or the U.S.,” recalls Dowd,” and it just wasn’t the right sound. That’s when we realized we had to go to Kabul to find our boys and much of the cast as well. We were not going to find them anywhere else!”

So it was that Dowd wound up on an odyssey literally to the other side of the globe to search for the right actors. Producer E. Bennett Walsh, who also served as unit production manager on THE KITE RUNNER, was instrumental in organizing Dowd’s trip to Afghanistan and making many of the introductions to lead her on her quest.

For an entire month, Dowd canvassed schools, orphanages and even the playgrounds of bomb-shattered Kabul searching for the ideal Amir, Hassan and also Hassan’s eventual son, Sohrab. She met one extraordinary, persevering child after another, and began shipping footage of the boys she met back to the U.S. Slowly but surely, she weeded down her list of candidates to a promising group of remarkably natural and soulful children, and then invited Forster, already on his way to Kabul, to make the final decision.

Forster was profoundly moved by the experience of coming to Kabul for the first time. Once legendary for its beauty and hospitality, the city has become a symbol over the last two decades of turmoil, tyranny and war – yet the warm spirit of the people still rises above it all. “This journey was essential for me to understand the Afghan culture, how people speak and relate to one another, and simply to see and feel what Kabul is like today,” says the director.

Rather than hold formal auditions, the first thing Forster did with the local Afghan children Kate Dowd had picked out was bring them outside to fly kites, to see them in a relaxed, playful, outgoing state of mind. It was then that he made his final casting decisions. Zekiria Ebrahami, a 5th grader whom Dowd uncovered in the local French Lycée, would play Amir. Ahmad Khan Mahmoodzada and Ali Danesh Bakhtyari, who were both found through ARO, the Afghan Relief Organization, would play Hassan and Sohrab.

As Amir, young Zekiria would have to traverse a lot of difficult emotions, from a yearning for acceptance from his stern father to the shame of betraying his closest friend in his time of greatest need, as well as the exhilaration of becoming the kite-flying champion. Yet, despite his lack of acting experience, he was a natural. “When I first met Zekiria, he was very shy and didn’t say much,” recalls Forster. “But there was something in his demeanor that was intriguing to me, a bit of a sadness somewhere. His father was killed before he was born, and his mother abandoned him. And it was because of this inherent sadness that I felt he would be the right choice to play young Amir who lost his mother and felt his father didn’t love him.”

Forster was equally compelled by the personalities of Ahmad Khan Mahmoodzada, who so movingly brings to life the spirit and resilience of Hassan, even in the face of his unjust fate; and of Ali Danesh as Hassan’s son, Sohrab, who seems to be following in his father’s unlucky footsteps until Amir comes to his rescue. Forster says: “Ahmad had an unbelievable spirit of life, a fighting spirit of sorts. He had energy and vitality and conveyed a sense of not being afraid of anything, of being willing to take a big bite out of life, which was so important for portraying Hassan. And Ali Danesh made me very emotional just looking at him. He has an incredible warmth and beauty and yet there is a distance you feel with him, an emotional wall, which is shared by Sohrab.”

The moment of finding the boys resonated thousands and thousands of miles away. “Marc called with that hair-raised-on-the-back-of-your-neck voice and said `I think I found the ones,’” recalls William Horberg. “And everyone who saw the boys knew right away he was right. Now we had a movie.” The book’s author, Khaled Hosseini, who had poured so much of his heart into creating Amir and Hassan as characters, was equally pleased with the casting selections. He observes: “Ahmad Khan who plays Hassan, is like a little man in a boy’s body and has this luminous face. When he smiles it just melts you and when you look at him you believe there’s somebody who is very pure, good and strong.”

He continues: “Zekiria, who plays Amir, has a fragile, wounded quality about him that is just beneath the surface yet shines through every once in a while. He also has that slightly shifty quality about him that Amir has as a little boy in the book. And of course being from Kabul, he’s a boy of 11 who has lived a lifetime. He’s been through some difficult personal hardships that most of us will never see and he brings that with him to this role.”

Hosseini concludes: “Danesh, who plays Sohrab, really impressed me with his intelligence and professionalism. Between takes, he is a playful and mischievous young boy who likes to goof around and play practical jokes. But when the word `Action’ comes out of the bullhorn, he instantly slips into character. It was uncanny to see how he was able to tap over and over again, in the blink of an eye, into the despair, melancholy and isolation of the Sohrab character.”

To gain permission to release the children from school and to wrangle travel passports for them, extensive negotiations over endless cups of tea and paperwork were required. “After Marc made his casting selections in Kabul, it took us three months just to process the cast!” recalls E. Bennett Walsh. “No one had birth certificates or ID cards, so we found ourselves in multiple meetings with government departments to get permission for issuing their passports.” With assistance from many people and agencies across Afghan society as well as through circuitous diplomatic and ministerial channels, everything finally came together.

Meanwhile, while still amidst the rich human resources of Kabul, Forster did additional casting. “We cast all the Afghan parts in the week that we were in Kabul,” recalls Walsh, “and it was an incredible accomplishment. I have never seen a director work before the way that Marc did. It was a very intense experience. Marc had never been in Afghanistan, so it was entirely new terrain and very gutsy of him.”

While in Kabul, Nabi Tanha, who has appeared on the Kabul stage and has directed and acted in several local movies, was cast in the role of Ali, who is both Baba’s servant and Hassan’s father. The veteran Afghan actors Abdul Qadir Farookh and Maimoona Ghizal also joined the cast as General Taheri and Jamilla, the San Francisco-based parents of Hassan’s wife, Soraya. Abdul Salam Yusoufzai, an electrical engineer and furniture maker who has dabbled in the Afghan film industry, was cast as the adult Assef. In addition, numerous amateur Afghans, most of whom had never acted before, let alone been in front of a camera, were cast in other supporting roles in the film.

Kate Dowd tried to prepare the actors for the often-surprising experience of their auditions. “Many of the Afghan actors have been influenced by Bollywood and have a much more theatrical style, so I had a few sessions with the ones I liked before I introduced them to Marc,” she explains. “In the end about 75% of the actors in the film came from Kabul and we were very happy about that.”

From Boys To Grown-Ups

Meanwhile, the filmmakers also set out on an extensive global search to find a mix of actors who could embody the complex, intercontinental lives of the main adult characters, including: the San Francisco writer whom Amir ultimately grows up to become; his noble but stubborn father Baba, who comes to find pride in Amir, yet holds back a secret about their past; Rahim Khan, the wise friend who gives life-altering advice to Amir; Amir’s wife Soraya, whose love helps him to make the decision to return to Afghanistan; and Farid, the driver who will take him into the heart of Taliban territory on the journey of his life. They scoured the U.S., Europe, Turkey and Iran, ultimately pulling together a remarkably diverse, yet highly accomplished, roster of men and women who each came to the project with a very personal relationship to the story.

The most important part of all was that of the adult Amir, whose momentary failing as a child will cause a heavy stone of shame to weigh down his heart throughout his life until he finally gathers the courage to set things right. Amir’s journey will take him through many of life’s core experiences – from experiencing loss to finding love, from realizing his dreams to closely escaping death, from forgiving his own human flaws to ultimately, paying the debt he owes to the man he comes to understand should have always have been his brother.

To play this central role the filmmakers chose Khalid Adballa, who had come to Horberg’s attention when he made an auspicious motion picture debut in UNITED 93 in the haunting role of the hijacker Ziad Jarrah. “A real piece of serendipity occurred when we were working on UNITED 93, which SKE co-financed with Universal,” explains Horberg. “There was a young actor who was part of that brilliant ensemble who had made a deep impression on me: Khalid Abdalla. I recommended that Marc and Kate check him out.”

The 25 year-old actor of Egyptian ancestry then blew Forster away in his audition. “I thought he was charismatic and brilliant,” says the director. “What’s going on in his eyes is tremendous and he can say vast amounts while being completely still. He conveyed all the layers I ever imagined Amir to have, and you see in him the spirit of a writer.”

“Khalid is an extraordinary young man and what he has done to reinvent himself as Amir in this film is just mind-boggling,” adds Rebecca Yeldham. “He really has become the character in the most heartfelt way and has given us a very sensitive and noble Amir.”

For his part, Abdalla was deeply drawn to this complex character, who like all of us, is driven by a yearning to be understood and loved. “I believe the burden Amir carries is on account of his love,” he says. “He did something that’s inexcusable, and some will blame him, but he was just a kid, and I think the guilt he carries suggests that ultimately, his sense of things is right. To me his personal journey to confront his past and live up to what his father wanted from him, and to live up to all that Rahim Khan hoped for from him, is a very courageous one.”

Prior to starting production on THE KITE RUNNER, Abdalla had never spoken a word of Dari, but he would have to speak both fluent Dari and English in the film, so he spent an entire month living in Kabul intensively learning the language. He succeeded to the extent that members of the Afghan community on the production couldn’t tell he wasn’t an Afghan. Abdalla did more than just absorb the language; he toured the city every day, soaking up the culture, and even receiving first-hand lessons in Afghan kite flying.

“When I was in Kabul I let the novel be my tour guide,” recalls Abdalla. “I went through the book and sought out every single detail of place, culture or food in Kabul and then went see what all these things looked like, tasted like or felt like.”

Khaled Hosseini was very impressed with the commitment and passion Abdalla brought to creating his portrait of Amir. “In my mind right now I can’t think of the adult Amir without thinking of Khalid Abdalla,” he muses. “It would be a great injustice if I didn’t mention the amazing thing he managed to pull off in going to Kabul for a month and learning the Dari language to the point that he is utterly and completely conversant. But most of all, when he went before the camera, the burden, the uncertainty, the trepidation, the guilt and troubled nature of Amir just came to life. He became somebody who is not comfortable in his own skin — which is not like him at all in real life.”

Much of Amir’s psyche has been formed in the shadow of his proud, strong-willed, academic father, Baba, who flees Afghanistan with his son when the Soviet Invasion threatens their world. To play the man whose love the young Amir feels he can never quite win, the filmmakers chose Iranian actor Homayoun Ershadi, who was educated in architecture at the University of Venice but presently lives in Tehran. Ershadi began acting in 1993 and it was his lead role in the acclaimed Iranian film A TASTE OF CHERRY, winner of the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, which launched his professional career.

Ershadi was challenged with creating a man who is fiercely intelligent and decent yet unable to connect with the son who he sees as so unlike him – only to come around years later to find a connection with him and express his love. “When I met Homayoun, I immediately felt there was an emotional quality in him that was very important for the character of Baba,” comments Forster. “If he didn’t have that ability to make people care for him in his most crucial scenes later in his life, then his strong characterization in the beginning of the film would not work. Homayoun makes that transition beautifully.”

A fan of the novel, Ershadi traveled all the way to Kabul to convince Forster he was right for the role. “I think one of the reasons Marc chose me is that he saw I’m acting from inside. I’m not acting from outside with my face or my body,” says Ershadi. Of his character’s transformation over the years, he says: “Baba is a very strong man but the problem with Baba is he doesn’t see himself in his son Amir. He sees himself more in Hassan than in Amir. He loves both of them and wants to see himself in Amir but he doesn’t so it makes him angry. In the end, everything has changed and Baba no longer needs to see himself in Amir. He’s a real father who shows his love.”

Khaled Hosseini was won over by Ershadi’s portrayal. “In the novel, Baba is this 6’5” guy who wrestles bears and he’s this big, larger-than-life character and Homayoun is not that,” he notes. “But he still conveys that gravitas, that sense of strength and presence. And when you see him scold Amir on the screen, you get the sense that this is truly somebody to be reckoned with.”

Meanwhile, to play Baba’s judicious friend, Rahim Kahn, who becomes the catalyst for Amir’s one last shot at redemption, the filmmakers turned to Shaun Toub, who gave a riveting performance as Farad in the Oscar-winning CRASH. “The first time I saw Shaun Toub in person, I instantly thought of him as Rahim Khan,” says Forster. “He has that mix of calmness, wisdom and kindness. Rahim speaks the truth and he is about the truth – and Shaun had all the qualities that could embody and convey his spirit and soul.”

Toub admires the way Rahim handles Amir’s emotions, as both a boy and a young man. “Rahim Khan is there to hold Amir’s hand, get him through the tough days, and make sure the love between Baba and him stays there,” he observes. “It’s really important to him to also make Baba understand that Amir is just not like him. I think he also helps Amir to understand that Baba truly does love him.”

Says Khaled Hosseini: “In the novel, Baba and Rahim Khan are life-long friends who know each other’s secrets, each other’s strengths and weaknesses and they’ve developed this shorthand language between them. Homayoun Ershadi and Shaun Toub have this same chemistry and rapport. They convince you these are people who have a great love and friendship between them.”

Also joining the cast is Atossa Leoni, an actress of Afghan and Iranian descent who has worked in film, television and theatre throughout North America and Europe, in the role of Soraya, who marries the adult Amir and supports him with great love on his journey to find himself. “Soraya is a very honest character,” says Marc Forster, “and for me Atossa really embodies that. She reveals a woman of many different layers: a traditional Afghan woman living in America, a portrait informed by being half Afghan and half Iranian herself, as well as someone with a wilder side. Not only did I feel all the turmoil in her character’s life but also a genuine connection between her and Amir.”

Says Leoni of the role: “I really admire Soraya and feel like I’ve learned so much from her. She’s sensitive, vulnerable and strong at the same time, and she’s a very classic female character. She has that ability to put admiration onto her husband without losing herself at the same time, and I find that very extraordinary. Her love story is a kind of search and I think a lot of people will identify with that search.”

Rounding out the main cast in the role of Farid, who leads Amir though a perilous Afghanistan during the time of the Taliban, is Saïd Taghmaoui, a seasoned actor of Moroccan ancestry who lives in France. Forster had seen him in “La Haine” and “Three Kings” and been impressed with his work. “He has an incredible power and strength. Saïd was a boxer and came from the street, lived on the street, and understands street life which was key for Farid,” the director comments.

Taghmaoui loved the part his character plays in Amir’s quest to face up to the consequences of his past. “He’s like a mirror to Amir,” he comments. “Farid is very frank, very real and very simple, and he tells the truth. It’s difficult to hear the truth especially when a guy like Amir is on his way to redemption. But when Farid brings Amir to see his old enemy Assef, he knows Amir has to face this alone to get back his respect and dignity and redeem himself.”

When he saw the entire cast assembled on the set as the living, breathing characters who had for so long existed only in his imagination, Khaled Hosseini was taken aback. “When I wrote the novel, I had a very clear mental image of what these characters looked liked, how they walked, how they looked at you,” he says. “But once I walked on the set, it was as if none of that existed. Suddenly my own mental image was supplanted and replaced by the faces, mannerisms, rhythm and speech of these actors. That speaks volumes about their ability as performers. It’s a remarkable thing that happened.”

From Afghanistan To Uighur

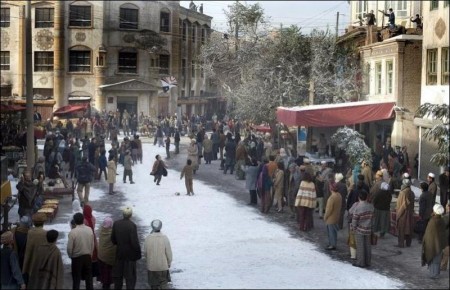

From the earliest stages of “The Kite Runner,” the question of where to shoot the film loomed over the production. The story would require the wholesale re-creation of several disparate worlds that no longer exist, including the vibrant Kabul of the 1970s – steeped in the thrilling and exotic atmosphere of many cultures freely co-mingling — which was all but eradicated during the Soviet invasion; and the Taliban-ravaged Kabul of 2000, at a time when the repressed country had become a dark shadow of its former self.

But where could the filmmakers possibly find the landscapes, architecture and settings of 3,000 year-old Kabul, the utterly unique Silk Road frontier town, in a place also capable of handling the logistical needs of a major film production? E. Bennett Walsh spent a year exploring some 20 different potential countries, but the surprise answer ultimately turned out to be Western China. Walsh was no stranger to China, having brought Quentin Tarantino’s KILL BILL VOL. 1 to shoot in that country, but it was in far-flung Central Asia, in the vast, sparsely populated Xinjiang Province, where he had never shot before, that he found the elements needed to realize Marc Forster’s vision for THE KITE RUNNER.

Walsh sent back photographs that revealed a majestic and haunting desert landscape between the ancient cities of Kashgar and Tashkurgan. They were starkly reminiscent of Afghanistan, which not coincidentally, it borders. This far-flung section of the fabled Silk Road (once the link between the Roman and Chinese Empires) is today a vibrant Islamic centre within Chinese society, where Indian and Persian influences abound. In the desert oasis city of Kashgar, a melting pot of cultures and colorful bazaars lend magic to a terrain that varies from the arid moonscapes of the Taklimakan Desert (which ominously means “enter and never leave”), to the dizzyingly high mountain ranges that surround it.

Still, bringing a feature film production to this remote area would be no easy undertaking. “Once we decided on China, there was an enormous amount of scouting and location work to actually come up with a plan,” says Walter F. Parkes. “That was as exciting and harrowing a ten days as I ever spent scouting a location. I don’t think I’ve been to a place that felt more foreign. There were moments, particularly when we would visit markets outside the main city, that you honestly felt you stepped into the 18th Century.”

When Marc Forster journeyed to Kashgar, he knew, that despite the obvious challenges the location would create, he had found the production’s main home. “I’d seen lots of photos of Kabul in the 1970s and, after visiting Kashgar, I knew it was right. It had everything we needed to make it real and authentic including the architecture, landscape and scope, as well as the extras,” he says.

Old Town Kashgar would ultimately serve as the prime location for most of the scenes of Kabul in the 1970s and in the year 2000, while the side streets across from the impressive and massive Id Kah Mosque stood in for Pakistani streets in Peshawar including Rahim Khan’s tea house. Constructed in 1442, the mosque is one of the largest in China, able to accommodate 10,000 worshippers.

For the dangerous escape of Baba and the young Amir from Afghanistan to Pakistan, as well as Amir’s journey back again decades later with Farid to rescue Sohrab, the production shot on locations along the famed Karakoram Highway, the highest paved road in the world, which weaves precariously through some of the most breathtaking mountain passes in the world. Additional scenes were shot at Karakul Lake at 13,000 feet of elevation, where cast and crew were housed in yurts, the typical tent-like homes of that area.

The smaller city of Tashkurgan, known as “the Stone City” for its 2,000 year-old ruins, became the setting for additional street scenes of Kabul in the 1970s as well as the haunting Kabul Cemetery, which Amir visits so movingly on his return. In addition, the production filmed for two weeks in Beijing — which momentarily became San Francisco. Three hours outside of Beijing, the production shot the terrifying scene of a Taliban stoning in Kabul’s Ghazi Stadium at the Baoding Stadium with 1,000 extras filling the seats.

After shooting nearly three months in China, the production moved on to the real San Francisco where they filmed the kite scenes that bookend the film at Berkeley’s Cesar Chavez Marina Park. Keeping the entire production focused and tightly knit in the midst of long journeys and profound culture shock became a key component of the production. “I think the story was what kept the cast and crew going,” says E. Bennett Walsh. “When things got hard, people knew they were telling a universal story that was important. Knowing we had something very special kept us together through the hard patches.”

Forster’s distinctive mix of skillful organization and openness to spontaneity also helped to keep the difficult path smooth. “Marc is a meticulously well-planned filmmaker and he pre-visualized the movie in his mind to an amazing degree,” says William Horberg. “He used all of that but also had the ability to really let go to find those happy accidents and serendipitous moments.”

“Shooting in these areas, you had to be open to the idea that anything could happen at any moment,” acknowledges Forster. “You had to be open to altering plans very quickly. It was the first time I felt pushed to the edge as a filmmaker because at times I wasn’t sure what was going to happen tomorrow.”

Intent upon leaving no negative trace on the local populace wherever the production traveled, Forster was thrilled at the cooperation that greeted the production at every turn. “It’s pretty amazing the impact the film had on areas where people hadn’t seen movie cameras, let alone too many Westerners,” continues the director. “There was a lot of curiosity, but overall they were just very welcoming and warm.”

With over 28 countries represented on the cast and crew, the languages spoken on the set spanned from English (from the US, UK, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa) to Dari and Pashto, Farsi (from Iran), Urdu (from Pakistan), Uighur (from Xinjiang Province), Tajik (Tashkurgan), and Mandarin and Cantonese Chinese, in addition to German, Spanish, French and Italian. It was sometimes only through charades that communication and collaboration somehow kept flowing. Notes Rebecca Yeldham: “It did provide great humor at times, as you witnessed a Swiss director communicating to an Afghan Dari interpreter as well as to his 1st AD who is American and to a Chinese AD who speaks Mandarin, who is communicating to an AD who is speaking Uighur, who is communicating to extras who maybe only speak Tajik!”

Sums up Forster: “I’m very proud of the cast and crew who gave their best even under these tough circumstances. I was very pleased with the performances, the landscape and everything we found in Western China, but truly it was the human connections we encountered there that shone.”

From The Epic To The Intimate

The full power of THE KITE RUNNER is brought to life not only through the performances but also via the painstaking design of the film, which attempts to bring a world and a culture rarely experienced by a Western audience to the big screen. To achieve this, Marc Forster recruited a crack team of artisans, including director of photography Robert Schaefer, ASC and costume designer Frank Fleming – both of whom have previously worked with Forster – as well as production designer Carlos Conti.

When it came to the film’s visual design, Marc Forster’s modus operandi continued to be the search for authenticity – which meant finding the means both to recreate the external details of Kabul and the internal emotions that underlie the mood of the story. He explains: “The challenge was in using color contrast, images and angles to convey the rich emotions of Hosseini’s story while also achieving a completely naturalistic look.”

The considerable task of recreating two Kabuls – one a burgeoning, colorful city in the 1970s, the other a shattered place of fear and oppression in 2000 — in the Western Chinese boomtown of Kashgar fell to production designer Carlos Conti, whose credits include THE MOTORCYCLE DIARIES and the Ellis Island epic THE GOLDEN DOOR. “We went after Carlos because when you look at his body of work, he has done amazing things on films of limited resources, where he’s gone out into the real world and found ways to modify and build on that to create great verisimilitude,” says William Horberg. “Carlos was masterful in his ingenuity on this film, finding details in China that have a real truth to them.”

Continues Rebecca Yeldham, who worked with Conti on THE MOTORCYLE DIARIES: “I’ve had the pleasure of seeing over and over again how Carlos so selflessly services the production with his relentless attention to detail. His is the kind of design that is often underappreciated because of its simple elegance and because it is so singularly dedicated to serving the movie as a whole.”

Marc Forster explains their process: “Carlos and I began by looking at images and reference pictures of Kabul and Peshawar and by the time we came to China, we had a very clear vision of what we wanted. We developed the idea of using contrasting colors — to make the 1970s as beautiful as possible and then by 2000, to make everything gray, draining the color out of it to reflect the starkness of the times.”

Once in Kashgar, one of Conti’s biggest challenges was finding the right location for Baba’s house, which represents the epitome of Kabul’s sophistication, class and style in its heyday. “We looked at a lot of photographs of homes in the once prestigious Wazir Akbar Khan District of Kabul, where Baba and Amir lived in the story,” says Conti. “We then created our own house in the architectural style of Kabul in the 1970s — but with the color schemes that we envisioned for the movie. We built the entire house in 8 weeks on an empty lot that previously had donkeys, sheep and chickens there. We built every piece of furniture and even created the paintings. The Chinese and Uighur crew were terrific.”

The true test came when Khaled Hosseini visited the set. “The house transported me right back to 1970s Kabul,” remarks the author. “Baba’s House is a very faithful re-imagining of what a house in Kabul belonging to people of a certain economic caliber looked like. It took me back to that time when Kabul was a cosmopolitan city, Afghanistan was at peace, and the image of Kabul that a lot of people are now familiar with did not even exist. It was moving to see the house, the city and the era of my childhood not necessarily replicated but re-imagined. It evokes a happier time in the country’s past.”

Another major location the production design team labored over was Kabul’s Kite Square, in which the spectacular kite-fighting tournament turns all eyes to the sky for the suspenseful battles. The scene was shot in Kashgar’s Ostangboye Square. “When I saw the square for the first time, I knew it was where the kite tournament should be. It was pure instinct,” says Forster.

The scene was a special thrill for Khaled Hosseini to watch unfold before his very eyes. “The kite flying tournament had to be one of the central visuals of the movie,” he says. “But what took me a couple of pages to write took an army to film, with 300 extras and people on rooftops, streets and phone poles. I was just in awe of how Marc was able to manage the logistics of what seemed to me unmanageable. I think in the final image, people will be able to really see how beautiful it was to have Kabul with the snow on the rooftops and children running around, and these multi-colored kites jostling in the sky.”

When Amir and Farid return to a very different Kabul, living under the steel-fisted Taliban rule, Conti’s idea was to contrast the bursting energy of children playing in the streets and vendors hawking their wares in the 1970s with an eerie, pained silence and stark nothingness. “I discussed with Marc the idea of having very little in the frame and no cars in the scene when Amir and Farid return. That creates a strong impression of a time when no one was allowed to fly kites, play music, watch television or go to the movies. It’s an image that, in a few seconds, allows you to understand what happened in Afghanistan. My goal was to work in these simple, strong images throughout the design,” he explains.

Also contributing to the naturalistic look of the film is the powerful work of director of photography Roberto Schaefer, who has collaborated with Forster on all his films, garnering a BAFTA nomination for FINDING NEVERLAND. Schaefer mixed the raw and the epic, relying largely on the existing lighting conditions available to him in Kashgar while at the same time filling the screen with sweeping imagery rife with awe-inspiring landscapes, textures and colors.

“The budget wasn’t epic but Marc and I both thought this should still feel like an epic film,” says Schaefer. “He wanted it to be as big and rich as possible, so I made the most out of everything that was available to us in order to show off the different periods, locations and landscapes to give the film scale.”

Shooting in the rugged deserts of Xianjiang posed numerous challenges, as the harsh reality behind the stunning vistas was often searing heat, lens-clouding dirt and the occasional rogue dust storm. With his reliance on natural light, Schaefer also often found himself doing battle with the sun’s ever-shifting directions, but he always found solutions. “Tough as they were, I never felt intimidated by the locations,” he explains. “We just figured out how to make them work the best way possible.”

Ultimately, the design and imagery of THE KITE RUNNER became far more than just the backdrop to the story. Rather, they are integral to the intended effect of allowing the audience to leave behind the familiar world for another. “I think what this movie can do is to make Afghanistan a real place for people,” says Khaled Hosseini. “I hope when people walk away from seeing THE KITE RUNNER, Afghanistan will seem to them like a place with hopes and illusions and dreams and wishes just like everywhere else in the world.”

Sums up Marc Forster: “In telling the story of THE KITE RUNNER we all went through our own emotional and personal journey that was filled with struggles and changes and realizations, and sometimes not knowing what was going to happen the next day. We got a glimpse of lives that are incredible, painful and hard in an Afghanistan that has endured 30 years of war. But at the same time, we encountered so many people with extraordinary resilience. And that is what stays with you – that people always have this ability to rise above.”

Production notes provided by DreamWorks Pictures.

The Kite Runner

Starring: Shaun Toub, Khalid Abdalla, Jonathan Ahdout, Nasser Memarzia, Said Taghmaoui, Navid Negahban

Directed by: Marc Forster

Screenplay by: David Benioff, Khaled Hosseini

Release Date: November 2, 2007

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for strong thematic material including the rape of a child, violence and brief strong language.

Studio: DreamWorks Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $15,800,078 (21.6%)

Foreign: $57,384,639 (78.4%)

Total: $73,184,717 (Worldwide)