Spain 1792 – the Catholic Church is at the height of its powers. The revolution has sent neighbouring France into turmoil and the Spanish church decides to restore order by bringing back the dreaded Inquisition. Spearheading this movement is the enigmatic and cunning priest Lorenzo, a man who seeks power above all.

Lorenzo’s friend is Francisco Goya, Spain’s most famous artist and portraitist to kings and queens. When his beautiful model Ines is unjustly imprisoned and tortured by the Inquisition their friendship is put to a test as Goya begs Lorenzo to spare the poor girl’s life. With the torture-ravaged Ines’ life in his hands, he rapes her and leaves her to rot in hidden dungeons.

Almost two decades later, just before the French armies invade Spain, Goya is a different man. Having lost his hearing entirely, he has become a dark, disturbed man, almost a ghost of himself. But it is now that he has entered his most famous creative period.

Lorenzo, having been banished by the Spanish church, fled to France, only to return in a new guise as chief prosecutor for Napoleon’s regime. Now he can take revenge on the very men that threw him out of Spain – he relishes the opportunity to persecute his old allies of the Spanish Inquisition. When the French abolish the Inquisition, all its prisoners are set free. Ines, the once beautiful figure of Goya’s paintings and dreams, emerges from prison not only having lost her youth but also to find her once powerful family slaughtered in their own home.

The only person she has left in this world now is the mad, old Goya. He becomes her protector and she reveals that she gave birth to a girl during her imprisonment. When Goya discovers Alicia, Ines’ daughter, working as a prostitute, he confronts Lorenzo who finally admits having raped Ines and being the father of her child. But mother and daughter are still far from being reunited.

The power map of Europe continues its seismic changes as Spain is once again thrown into chaos when Wellington’s powerful army invades to restore Spanish rule. Lorenzo finds himself in desperate need of a new ally of faces a gruesome death sentence. It is mayhem on the streets of Madrid and Goya continues his desperate struggle to reunite mother and daughter. Lorenzo will stop at nothing to save himself and keep secret the child that haunts him…”

Production Information

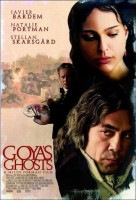

Production began in Spain on September 5, 2005, on Milos Forman’s historical drama Goya’s Ghosts, starring Javier Bardem (The Sea Inside), Natalie Portman (Star Wars, Closer) and Stellan Skarsgard (Good Will Hunting). Milos Forman directs and Saul Zaentz produces.

Goya’s Ghosts starts off in Spain in 1792 and tells the story through the eyes of the great Spanish painter Francisco Goya of a group of people caught up in a time of political convulsion and historical change. The action takes place from the later years of the Spanish Inquisition through the invasion of Spain by Napoleon’s army to the ultimate defeat of the French and restoration of the Spanish monarchy by Wellington’s powerful invading army.

Javier Bardem is Brother Lorenzo, an enigmatic, cunning member of the Inquisition’s inner circle who becomes involved with Goya’s teenage muse, Ines (Natalie Portman), when she is falsely accused of heresy and sent to prison. Stellan Skarsgard plays Francisco Goya, the celebrated painter renowned for both his colorful court paintings and his grim depictions of the brutality of war and life in Spain.

Goya’s Ghosts, a Xuxa Production S. L., in association with Kanzaman Films is directed by Milos Forman and produced by Saul Zaentz from a screenplay by Forman and Jean-Claude Carriere (Birth). Paul Zaentz is executive producer. Co-producers are Denise O’Dell and Mark Albela.

Forman and Zaentz previously collaborated on the Academy Award winning films One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Amadeus. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest received nine Oscar nominations, winning five statuettes include Best Picture and Best Director. Amadeus was nominated for 11 Academy Awards and received eight Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director.

Forman’s most recent film is Man on the Moon. He has also directed The People vs. Larry Flynt, Ragtime and Hair, among other productions. Saul Zaentz’s most recently produced The English Patient swept the Academy Awards for 1996 with 12 nominations and nine Oscars.

Jean-Claude Carriere collaborated with Milos Forman on Valmont and Taking Off. He is author of more than 100 screenplays including Luis Bunuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and That Obscure Object of Desire.

Director of photography is Javier Aquirresarobe who won the 2005 Goya Award for The Sea Inside. Academy Award winner Patrizia Von Brandenstein (Amadeus) is production designer. Her most recent film is All the King’s Men, due for release September 2006. The costumes are designed by Academy Award winner Yvonne Blake (Nicholas and Alexandra) who received the 2005 Goya Award for The Bridge Of San Luis Rey.

About the Production

The idea to make a film about the great Spanish painter Francisco de Goya and the Spanish Inquisition first occurred to Milos Forman more than 50 years ago when he was a student in Communist Czechoslovakia.

“It didn’t really start with Goya at all,” Forman recalls. “It started when I was in film school and read a book about the Spanish Inquisition and an incident in which someone had been falsely accused of a crime.

“I thought this could be the heart of a wonderful story. There were a great many parallels between the Communist society we lived under and the Spanish Inquisition. I knew, of course, a story like this could never be done in Czechoslovakia because of such similarities. So I forgot about it. For the time being.”

But good ideas don’t die even if they fade away temporarily. They endure in the recesses of the mind, and this idea was no exception. Thirty years later it resurfaced, not surprisingly in Madrid, where Forman and independent producer Saul Zaentz were promoting Amadeus, their second Academy Award winning collaboration that followed nearly ten years after their first triumph, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. “Milos and I were staying across the street from the Prado Museum in Madrid when he remarked to me he had never seen the famous Hieronymous Bosch painting Garden of Earthly Delights, one of the Prado’s greatest holdings,” Zaentz remembers

“But the Prado holds many other masterpieces, including the greatest collection of Goya paintings, and we looked at those. We’d seen them, but never live, in person. They were marvelous. One struck us, the painting of a dog. When you see it reproduced in a book you imagine it must be movie-screen size because it’s so wonderfully done. In person you discover it’s not big at all, maybe a meter and a half, but you’re not disappointed. The dog is very touching and you carry the image with you.”

Goya fascinated Forman. “I was overwhelmed by his paintings and couldn’t stop thinking about him,” he says. “I was convinced Goya was the first modern painter. More than ever I wanted to make a picture about him.”

During the Prado visit Forman related to Zaentz the incident about the Inquisition he had read so many years before, and he discussed his idea of making a film that dealt with the Inquisition in combination with Goya. Zaentz understood it could be a wonderful movie.

“But I told him it was necessary to come up with a story that could support the idea, a story we had both confidence in and were passionate about in order for us to move ahead,” the producer said. Forman agreed.

As time went by, producer and director continued to talk over the idea for the film, and even considered a particular writer to draft a screenplay. But, in fact, Forman had a favored collaborator in mind, the renowned screenwriter Jean-Claude Carriere, with whom both he and Zaentz had worked successfully in the past.

“Jean-Claude is like a spiritual brother to me,” the director says. Forman and Carriere first met forty years ago in 1966 at a film festival in Sorrento, Italy. By then Forman had directed several features, including Black Peter and Loves of A Blonde, and Carriere had collaborated with the great Spanish director Luis Bunuel on the screenplay for Diary of A Chambermaid, and with Louis Malle on the script for Viva Maria.

Forman and Carriere stayed friends after Forman left Czechoslovakia, and throughout several collaborations (Taking Off, Valmont). Over the years they were always in contact.

“Yes, I was intrigued by Milos’s idea – well I wouldn’t call it an idea – it was, rather, a desire to do a film not exactly about Goya, but about Spain during Goya’s time,” Carriere says. “And Goya would enter into the story naturally because it was the time period in which he lived, a turbulent period.

“This is a very interesting time frame. The end of the 18th century and beginning of the 19th is probably one of the most important periods in European history because of the French Revolution and the advent of Napoleon. France was the center of Europe at the time and it’s interesting to see all the consequences of what was happening there, and how they affected Spain, especially once Napoleon invaded the country.

“Spain at the end of the 18th century was probably, despite a certain modernity, the most backwards nation in western Europe. It was Catholic, conservative, ruled by a monarchy whose King belonged to the same family as the French King. The works of the great 18th century philosophers and the Enlightenment had almost no influence there. The Inquisition was still in operation, still capable of inflicting terrible damage on the populace. Milos was fascinated by the era, and the Inquisition.”

“What was so attractive for me about this particular period,” Forman says, “was, with so many paradoxes and so many changes going on, it reflected the times I had lived through, first a democratic society, then the Nazi society, then the communists, then democratic again, and then the communists again and then democracy once more.

“And that’s very similar to what the situation was in Spain at the beginning of the 19th century. King Carlos represents the old guard when suddenly Napoleon invades and brings progress, the ideals and values of the French Revolution. But what is that? It reminded me of the time in my own life when the Soviets brought `liberty’ to Czechoslovakia.

“Instead of real liberation in Spain, Napoleon installs his brother on the Spanish throne until the British, under Wellington, invade, chase out the French and restore the repressive Spanish monarchy. Very interesting period.”

Carriere and Forman were convinced that Goya was the perfect figure though which to tell the story of those times. Goya was born long before the French Revolution and died long after. “I don’t think Goya was politically involved consciously. He was just an incredible observer, like a journalist,” Forman says. “He was commenting, recording what he witnessed. As he says in the film, `I paint what I see’.”

Carriere says, “Goya painted the kings and queens of Spain, their children, the whole family, and was admitted inside the Royal Palace, also painting the people at court. But at the same time he knew about ordinary life. He walked the streets, went to the taverns and he did sketches and engravings, many of which, Los Caprichios and the Disasters of War are so famous, and rightly so. He even did a portrait of one of the Inquisitors, and also the brother of Napoleon who was installed on the Spanish throne, as well as ordinary citizens and soldiers. He understood the heart of everyone.”

In terms of the film they wanted to make, Forman, Zaentz and Carriere understood that a simple Goya bio-pic or a didactic depiction of the Inquisition would not work. What was wanted was a fresh approach, and the filmmakers continued to mull over the project, steeping themselves in the history of Spain, concentrating on the period, reading everything they could find on Goya and the Inquisition.

Forman and Carriere, who speaks Spanish and knows the country, even spent several weeks driving around the Spanish countryside, making a second trip with Saul Zaentz, trying to deepen their understanding of the country and its culture.

Screenplay

In 2003, nearly 20 years since Forman and Zaentz first discussed their idea in the Prado, the filmmakers got down to work on the Goya project in earnest. Forman and Carriere retreated to Forman’s home in Connecticut which provided the proper solitude and discipline for writing and, working ten hours a day, were able to come up with a first draft of a script.

“One characteristic of Goya which Milos and I felt fit our purpose was his commitment to his art,” Carriere says. “He’d paint anyone, an inquisition minister, or the Duke of Wellington who freed the Spanish from the French. He was basically apolitical. He didn’t want to be involved in politics, in action, in social improvement. He just wanted to paint.

“We thought it would be interesting in the film to oppose this character of Goya with another man who is his acquaintance, his opposite in temperament and philosophy, an intelligent man who is devoted to changing the world and very much involved in the political movements of his time. And this man, Brother Lorenzo, became the main character of the film, a priest of the Inquisition, an Inquisitor himself who fanatically believes in building a better and more human world based on the teachings of Jesus.

“He believes that the moral decline of Spain is due to the fact that the Inquisition has lost its severity in the guarding of those teachings. He wants to revive the power of the Inquisition and restore it to its original force and influence. At the same time, he’s learning about tendencies making their way into Spain from revolutionary France which contradict prevailing religious doctrine because they are trying to establish the principle of man as the creator of his own destiny based on the philosophy – liberty, equality, fraternity.”

The third principal character in the story is a woman acquainted with both men, Ines Bilbatua. She starts out in the story as Goya’s teenage muse but later becomes involved with Brother Lorenzo when the Inquisitor becomes her only hope of fighting the accusation of heresy against her.

“Ines is a young Spanish girl from a well-known family. Her father is a wealthy merchant, and the Bilbatuas are good Christians,” Carriere says. “But because one night when she’s out with her brothers and friends in a public tavern, she’s spotted by Familiares who spy for the church and suspect her of hiding Jewish practices. This sets the story going because the innocent young woman is called up before the Inquisition and questioned. And then the horrors begin.”

Casting

Forman and Carriere, with Zaentz’s guidance and encouragement, worked intensely on several drafts of a screenplay before they completed a script that met everyone’s approval. Once this was accomplished, Zaentz arranged the financing and gave the go-ahead to make the film. Pre-production began with the filmmakers moving forward on two fronts: they began the process of choosing locations, and also started to assemble a cast.

Director, producer and writer were of one mind on each of these issues. As for locations, each man believed it was essential for the spirit of the film and for its authenticity that Goya’s Ghosts be made on location in Spain, with as many Spanish actors and crew members as possible. Forman and Zaentz’s previous collaborations were all made on location. This film would be no exception.

With this in mind, long-time Milos Forman collaborator, production designer Patrizia Von Brandenstein, Oscar winner for her work on Amadeus, was brought in to discuss Spanish locations. Von Brandenstein had worked with a local production company in Spain several years earlier that she believed could help find the proper places to shoot and to set up facilities for making the film there.

In fact, producer Zaentz was acquainted with the very same organization, having produced his animated version of The Lord of the Rings with them in Spain in 1978. The head of the company, now called Kanzaman, was an English-born production executive who had been living and working in Spain for many years, Denise O’Dell.

Zaentz traveled to Spain to meet O’Dell and discuss the Goya project with her and Kanzaman co-director Mark Albela. “I was thrilled when I heard from Saul about the project,” O’Dell says. “Here were two legends of cinema planning to come to Spain to make a film, Zaentz and Forman. I was so eager to become involved.

“And then when we met and they told me that they weren’t interested in bringing a big crew from abroad but were interested in using Spanish talent, well that for me was just wonderful because it’s been what we’ve been trying to do for years.”

With Kanzaman on board, and location scouts being arranged and organized, Forman and Zaentz addressed the crucial task of casting.

From the start Forman and Zaentz were eager to have Javier Bardem appear in the film, convinced he would be perfect for the role of Goya. Bardem, who was nominated for an Oscar in 2002 for his role as the Cuban poet, novelist and dissident Reinaldo Arenas in Julian Schnabel’s Before Night Falls, is one of Spain’s most popular, charismatic – and accomplished – young actors.

“Javier is definitely without question one of the major screen actors working today,” Zaentz says. “In the beginning, we pictured him as Goya, and we made plans to meet in the Ritz Hotel across from the Prado. We were thrilled to see him in the lobby, even happier when he walked up and said, `I want to make a movie with you guys!’ I put my hand out quickly and said, `We want to make a picture with you’.

Bardem recalls the incident with pleasure. “When my agent called and said Milos Forman and Saul Zaentz wanted to meet me I thought it was a joke at first. But when I met them I understood it was real, and I was thrilled. And of course, because I’m Spanish, I assumed I’d be playing the role of Goya. It seemed the natural thing.

Unknown to Bardem, the conception of the character of Goya was changing in the script. The fictional character Lorenzo, not Goya, had emerged now as the film’s protagonist.

“We all understood after many discussions that our story wouldn’t work with Goya as the main character,” Zaentz says. “He was all important and crucial to the story. But he wasn’t the main protagonist.”

Father Lorenzo was the role he and Forman wanted Javier Bardem to play. “When several days later Javier asked us how the film was going, we told him something had come up that was going to affect his part but not do anything at all to the impact he would make in the film,” Zaentz says. “He was intrigued. But instead of over-explaining what we wanted, we said we would send him the completed script so he could see for himself the changes and understand the logic of why we thought he should play Father Lorenzo.”

Within hours of reading the script, Bardem phoned Forman and Zaentz with his reaction. “Lorenzo has my heart,” he said, and he agreed to play the role.

The role of Lorenzo fascinated the actor. “I understand it’s a challenge not to be playing the character people expect. It’s an even greater challenge playing Lorenzo. He’s a man of hard and strong beliefs. I would call him a fanatic. But he’s not a villain, not a mad guy, just a man of passion, sometimes uncontrollable.”

Casting the role of Goya came next and presented the filmmakers with a particular challenge: Forman believed that the actor who was going to play Goya needed one attribute above all.

“I didn’t want the actor playing Goya to be someone recognizable,” the director says. “For the fictitious characters, Lorenzo, Ines, it didn’t matter to me if a famous face fills the role. But Goya. Goya will come out of nowhere. Unexpected. We shouldn’t recognize him from anywhere else.”

Early in the process it appeared that Goya had been found. “I remember that Milos and I were returning from Europe to America by plane,” Zaentz says.” Milos was watching a movie, not a good one, one of the Exorcist installments, when he turned to me and said, `There’s our Goya.’ And I said, `Where?’

Milos pointed to the screen and to Stellan Skarsgard who was a lead in the film. “’I know him,’ I told Milos. He had a role in The Unbearable Lightness of Being which I produced. I thought it was a great idea.”

A Swede, Stellan Skarsgard is best known to US audiences for his roles in Good Will Hunting and Breaking the Waves, but he is definitely not a household name. “Skarsgard is the kind of actor you remember not as Stellan Skarsgard but as the character he plays in each particular film,” Zaentz says. “He’s a marvelous actor.”

Skarsgard was delighted to be approached for the part. “I’m physically different from Goya,” Skarsgard says. “But of course it’s not Goya as he was in real life that we’re depicting. This is fiction film.”

Natalie Portman, Golden Globe winner and Academy Award nominee for Mike Nichols’ Closer, was cast in the role of Ines Bilbatua, Goya’s youthful muse. Strange to say, Forman wanted the young star for the role without knowing exactly who she was.

“I didn’t know Natalie Portman at all,” Forman says. “I had bought a copy of Vogue or a similar fashion magazine and was reading it to relax when I was struck by the photo of the young woman on the cover who turned out to be Natalie. And as I’m looking at it, I open a book about Goya’s last painting in Bordeaux called A Milkmaid in Bordeaux, and I see they are the same face.

“So I started to make inquiries about the qualities of this actress and I saw how much people like her. And then I saw the film Closer and saw how good she is and knew that I wanted her. Her range is amazing, big, surprising, and that was very important here. Basically she plays three different characters in the film.”

“When I went to Paris to meet with Milos and Jean-Claude, I was surprised to discover that they wanted me in the film at first not because they’d seen my work but because the saw a photo of me and decided I looked like a young woman in some of the paintings,” Portman says.

“I was interested and intrigued to meet them, and a little intimated, too, because I love Milos’s films. I was ready to read or test for the role, whatever they wanted. When they offered the part I was very excited. Ines figures in a part of history I never knew about. It was something terribly different from what I’d done before.”

Two other important roles were cast with well-known international actors. Randy Quaid, who recently appeared in Ang Lee’s Academy Award winning Brokeback Mountain, co-stars as King Carlos IV of Spain. And distinguished French/English actor Michael Lonsdale was signed to play the role of the Grand Inquisitor. Lonsdale’s notable career includes films by Fred Zinnemann (Day of the Jackal), Francois Truffaut (Stolen Kisses), Louis Malle (Murmur of the Heart), and most recently Steven Spielberg (Munich).

Other key roles were filled by some of Spain’s most gifted actors, including Jose Luis Gomez (The Bridge of San Luis Rey), Mabel Rivera (Sea Inside), Raymond Guerra, Blanca Portilla (Volver), Unax Ugalde, and many others. As the casting process moved along, Forman and Zaentz staffed the film with some of Spain’s most talented and creative technicians.

Director of photography is Javier Aguirresarobe whose credits include two films by the Spanish director Alejandro Amenabar, The Others starring Nicole Kidman, and The Sea Inside. Aguirresarobe is a six-time recipient of Spain’s Goya Award (the equivalent of the Oscar) for cinematography.

Academy Award winner Patrizia Von Brandenstein (Amadeus), one of Forman’s most valued collaborators reunited with him for the fifth time on Goya’s Ghosts, is production designer. Von Brandenstein’s recent credits include Harold Ramis’s The Ice Harvest and Steven Zaillian’s upcoming All the King’s Men.

Academy Award winner Yvonne Blake (Nicholas and Alexandra) is costume designer. Ms. Blake’s distinguished career includes some of Spain’s most notable film productions. She was also nominated for an Oscar for her work on Richard Lester’s The Four Musketeers.

About Filming

Production on Goya’s Ghosts got underway September 5, 2005 with Forman shooting several sequences that take place inside Goya’s studio where Von Brandenstein recreated the master’s workshop on the first floor of the main structure of a collection of abandoned buildings that had once been a working farm near Madrid in the small town of San Martin de Vega. Here Forman shot Goya painting Ines’s portrait, followed by a scene in which Brother Lorenzo poses for his.

Scenes depicting the painstaking process of Goya creating a series of etchings were filmed inside the artist’s workshop, while those set in a mental institution and in the dungeons where the Inquisition kept prisoners they’d secreted away were also filmed at San Martin. San Martin’s farmhouse dates from the 16th century, yet the farmstead, with its compact complex of one-and-two story buildings and open spaces, lent itself effortlessly to the exigencies of filming. No desired space went unused.

“In its heyday the farm slept three hundred people,” executive producer Paul Zaentz points out. Paul Zaentz has worked with Saul Zaentz on all the producer’s Oscar winning films.

“We utilized everything in the place. One-time grain and farm equipment storage units in the basement became our dungeons. Each of the two of the barns became sets. One barn was transformed into an interrogation chamber, and the other was used to build prison cells.”

Taking a temporary break from work at San Martin de Vega, the unit shifted location to the center of Madrid, to film inside the city’s beautiful Retiro Park. Then, after returning to San Martin for several scenes involving Ines, Lorenzo and members of the Inquisition, the unit traveled two hours north to the city of Segovia where Forman staged the dramatic sequence of Napoleon’s Army invading Spain. With its pedestrian alleyways where no cars are allowed, its restored ancient city center, and its profusion of Romanesque churches, Segovia functioned as a perfect stand-in for Madrid as that city looked over 200 years ago.

In the central square of Segovia’s old town, Forman used two units, the main company, and a second unit supervised by Michael Hausman, Forman’s longtime production associate. Both units filmed French soldiers on horseback storming the city along with troops of Mamelukes, the ancient military caste that once ruled Egypt whose forces Napoleon added to the French Army. The French run riot in the streets, `liberating’ Spanish citizenry and causing general havoc, raping women, pillaging merchants’ wares, killing indiscriminately.

In Segovia’s small central square of San Martin with its austere Romanesque architecture, Forman also filmed several important scenes that take place at the entrance of the Bilbuatua mansion.

Returning to Madrid, the unit next filmed on the landscaped grounds and inside the elegant and opulent rooms of a succession of Spanish royal palaces, all of which are situated on the outskirts of the city. Each of these palaces, Vinuelas, El Pardo, and La Quinta, is considered an essential element of the Spanish National Heritage – the country’s Patrimonio.

Inside the palace at Vinuelas, in north Madrid, Forman shot an important sequence in which Queen Maria Luisa of Spain poses for Goya as he paints the well-known portrait of her astride a horse, when the sitting is interrupted by the arrival of King Carlos, returning from a hunt. The King out shooting with his courtiers was filmed on the grounds of Vinuelas, an idyllic stretch of rolling hills populated by a herd of deer running free.

Also filmed on the grounds was a scene in which Lorenzo, now a member of the Bonaparte government ministry, is accosted by a group of armed peasants.

Not far from Vinuelas, on the royal grounds of Monte de El Pardo, a wooded parkland that is one of Madrid’s largest natural areas, Forman shot sequences at two grand palaces located there.

The Royal Palace El Pardo, a hunting lodge that dates from the period of the Hapsburgs and is richly decorated with frescoes and tapestries, stood in for the royal palace of Madrid where Goya, invited into King Carlos’s drawing room, witnesses the King hearing from a messenger the gruesome news of the execution by guillotine of his cousin, King Louis XVI of France during the turmoil of the French Revolution.

Also filmed at El Pardo was a scene with Napoleon in discussion with his ministers, as well as the episode in which Ines’s family is granted an audience with King Carlos and pleads with him to intervene with the Inquisition on their daughter’s behalf.

At La Quinta, another hunting lodge on the grounds of Monte de El Pardo that had been converted into a one-time residence for the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, Forman staged several scenes set in the home and office of Lorenzo in his capacity as Bonaparte government minister.

An intensely dramatic sequence in which Goya confronts Lorenzo along with a radically changed Ines was shot there, as well as a scene in which Goya tries to thwart Lorenzo’s devious plan to exile all the known harlots in Madrid to America.

Next the unit moved once again from Madrid to hilly countryside near the town of Ocana not far from the city of Toledo. On a wide expanse of rolling hills, Forman filmed a huge sequence depicting the Duke of Wellington and his vast army crossing over the border from Portugal into Spain, repulsing the occupying French forces and liberating the Spaniards.

The director then shot a second military scene occurring some years earlier in the action, a French commander addressing his massed troops in an encampment before they march on Spain, in the higher mountains in the Ocana countryside.

The epic nature of the story and the large-scale effects involved in Goya’s Ghosts – huge panoramas alternating with intimate scenes of high drama, each with a particular intensity, not to mention the re-creation of a specific historical period — was a challenge for everyone involved in the film, cast and crew. But perhaps no one, except for Forman, was more involved in the physical aspect of production than production designer Patrizia Von Brandenstein.

“It’s an overwhelming proposition and you’re confronted straight off the bat with just how do you approach re-creating the era, not to mention the works of Goya and a million other details, for a director as demanding as Milos,” von Brandenstein muses.

“And what you do is to start with the obvious, the paintings and the literature and the historical writings on the period. There are so many books written about Goya and that period of Spain. But I like to go directly to the letters. Letters written by the Duchess of Alba, letters from Queen Maria Louisa and the King are all available in English, and they provide a wealth of material.

“Then of course you have to address technical issues because of showing Goya and the paintings. Goya’s importance to the Spanish cannot be overestimated. It’s unique. He’s a kind of father figure to the country.”

Javier Bardem, a Spaniard of course, attests to the truth of this. “Spanish people revere his work,” Bardem says. “I think Goya is the very first painter for whom art functioned as a kind of journalism. He was the first artist who was able to paint the king, the richness and glory of the Spanish monarchy that contributed to the creation of the Spain we have today.

“But Goya could also paint the misery of the street, the horror of those times, with the same flavor, the same point of view with which he portrayed majesty. In everything he paints, he’s attached emotionally to what he’s observing.”

Carmen Ruiloba, a historical consultant for Goya’s Ghosts, explains the significance of Goya to the Spanish people. “I had a college professor who used to say that Goya is part of the family. For every Spaniard he is your grandfather. He’s a universal painter, a genius who speaks directly to the heart of the people and who talks for the future. What he said two hundred years ago about war, about beautiful duchesses, about the common man in the street, about the poor and stricken, it’s all still valid today. “In terms of academics, Goya is crucial in the history of art. Many would say he is the first modern painter. He is the link between classicism and modernism.”

Such a character is a test for any actor. Stellan Skarsgard worked long and hard to get under his skin. “Let me tell you, I spent an incredible amount of time researching Goya himself. Actually all of us involved in the film immersed themselves in the essence of who and what Goya was, and how he worked and lived,” Skarsgard says.

“We went so far in this direction that for some of those scenes in the studio we followed his formula for etchings and probably could have produced some. We know the formulas he used for color and the paints he particularly liked. We were even able to re-create the sketchbooks he used. He carried them with him wherever he went, something he learned about in Italy and brought home with him.”

The verisimilitude of the setting and the atmosphere on set helped Skarsgard to embody Goya as a living, breathing human being.

“But understanding his soul from inside, the soul of the character that Milos Forman and Jean Claude Carriere have created, is the goal. “I work from seeing him as they created him. The character as written is very interesting because he has compassion towards everything he paints. Yet he’s someone who stands apart as some artists must do. He certainly doesn’t want to get in the way of the powers of the Inquisition and he certainly respects his young muse Ines, though in some way he’s obviously in love with her. Whenever he paints angels in a church or whenever he needs the face of a lovely young woman in a painting, it’s her face he uses. She’s constantly alive in his mind.”

Bardem stands in awe of his Swedish co-star. “The relationship between Goya and Lorenzo, the character I play, is the relation of people who respect each other and fear each other, too. Goya is a free man who depends only on himself. Lorenzo is a man who relies on dogma, on ideas, the power structure of the time. He has power in society while Goya does not.

“To see how Stellan, this man from the north of Europe creates this character who is the soul of Spain is something of a miracle. To work with Stellan is to slide on silk. You have an amazing actor there.”

Forman joins in the praise. “Subtlety, subtlety is the key. It’s a danger to make artistic geniuses like Goya bigger than life, different from ordinary people in the manner, in the way they live. Stellan is so subtle. I believe every word he says, every gesture he makes.”

In the final analysis, each of the principal actors in the story, whether portraying a historical personage or a fictional creation, shares a similar task: each plays a figure in a screenplay that must be brought to life on the screen. Unlike Stellan Skarsgard, Javier Bardem and Natalie Portman had no objective standard on which to base their characterizations. They had to work wholly from the imagination. Yet Portman was able-instinctively-to relate to a young woman like Ines and the tragedy that affects her life in the context of the era in which it took place.

“I read several books about women who were put through the Inquisition and their testimony, the extraordinary transcripts of the women who were tortured and whose words are almost identical to Ines’ dialogue in the film. `Just tell me what you want me to say, what the truth is!’ she pleads.

“I understand the film takes a bit of historical license in terms of the time frame. At the point our story takes place the power of the Inquisition was somewhat diminished. Nevertheless this kind of thing happened.”

Portman also found herself fascinated when she learned about the position Goya holds in the heart of the Spanish people.

“I think Goya’s paintings, particularly the later paintings, the Black Paintings, reflect something deep in the Spanish character. One of the books I read in preparation for filming mentioned something that stayed with me, it said `Death is the patron saint of Spain.’ And I think it’s true. Look at bullfighting-there’s a sense in the culture of being close to death. You feel death everywhere and somehow that makes life even more vibrant.”

Following the work at the royal palaces and Ocana, the unit traveled north to the province of Aragon and the medieval monastery of Veruela for scenes set inside the power corridors of the Inquisition. Exteriors of Inquisition headquarters were then filmed in the medieval city of Salamanca, home of the oldest university in Spain and Europe.

These locations mark the place from which Father Lorenzo starts out in the film. As a man of the cloth he is very much a part of the institution he serves, and Bardem struggled to understand exactly what motivates such a human being.

“The first thing I did once I was cast was to read as many books about the period and also talk to people who were expert in the era,” he says. “I also spoke to a couple of priests who of course didn’t live in those times but who understood them. I felt they could help me figure out what kind of character Brother Lorenzo could be.

“But of course since this is a fiction movie, there comes a moment when you have to forget everything you studied and simply build a character. Otherwise you are too attached to what you think the character should be and you’re not free enough to construct or build one on your own.

A big challenge for Bardem was to unite the two opposing personas in Lorenzo’s character. “I worried about connecting the two but there are traits, psychology that link the two. Mainly it was very important to make Lorenzo a normal human being with his own desires and goals the audience can understand. We don’t want him to be a villain. He’s a man trying to do the best he was taught under difficult circumstances. “The hard part is shooting out of sequence. One day you are Dr. Jekyll, the next Mr. Hyde, then three hours later Dr. Jekyll again.”

The fictional nature of the story, that the drama is based on fact but is nonetheless a work of the imagination, remained a guiding principle throughout filming for everyone involved in the production. Prado Museum associate Carmen Ruiloba, one of Goya’s Ghosts historical consultants, recognized Forman’s interpretation of history and the manner in which he approached the events of the past. “Milos is so imbued with Goya’s work. The paintings inspire him. Some of them are even recreated for the camera, The Abolition of the Inquisition, Queen Maria Louisa on Marechal, an Inquisition Scene that’s in the Royal Academy, and so many others.

“But beyond the paintings, Milos takes his concept of how he sees the history and themes of the period and transforms them in his story in the most artistic manner possible. He is working, if I may say so, like the great Spanish painter Velasquez, “For example, in his magnificent17th century painting Surrounding the town of Breda, Velasquez painted something that never happened. He wanted to convey in this painting the nature and temperament of the Spanish general who had conquered the town but who treated the subjugated populace humanely. So he painted the victorious Spanish general standing on the ground in front of his horse, facing the man he defeated and putting his arm around him. It never happened. Not for a minute! The Spanish general would never, never have dismounted in such a situation. But Velasquez wanted to show the good character of the general and the concept of mercy, and that’s what he painted. The man is off his horse. The concept is true.

“Milos works here in a similar vein. Certain details are changed but the truth is never distorted. He asked in one scene if, when the French army invades a church to declare the end of the Inquisition and a mass is underway, would the priest be singing as he’s being struck down. I told him I didn’t think so but that in order to make his point I thought it was perfect. He wanted to show the French behaving like true invaders, interrupting the natural order of things, killing people. A singing priest being stuck down is a such a vivid image-we get the truth, the reality of the situation.”

The dynamics of Forman’s direction, his ability to bring alive in all its complexity a dramatic scene set two hundred years ago was something that inspired everyone on Goya’s Ghosts, both cast and crew.

“Milos is not at all what I expected,” says Natalie Portman. “Watching his films I expected him to be super intellectual-well, he’s incredibly smart and well read, and if he wanted to I have no doubt he could be a super intellectual. But he’s almost an anti-intellectual. He’s not about making things overly complicated or doing everything by the book. You know he wants to get the major detail right but then he wants to let everything else go and just create his own portrait. And it becomes a feeling portrait.”

Javier Bardem is also affected by Forman’s working methods. “Perhaps the most amazing thing to me is Milos’s sense of humor. It is there everyday, for five months. It never deserts him even when things are at their most difficult. And then when he gives you direction, it’s like a blessing, because he knows so much about acting, about truth. It makes working so enjoyable. Every day becomes special.

“Some days I wake up in a state of shock. Here I am a Spanish actor working with these amazing actors in a film being directed by Milos Forman and produced by Mr. Saul Zaentz from a great script by Milos and Jean Claude Carriere.

“I feel like I’ve lived through an experience with these men that not only helps me professionally but also helps with life because these are people who work with an open heart and a great sense of purpose.

Forman’s humor made a particular impression on Stellan Skarsgard. “He is of course a fantastic director but he is so funny. Between takes, we don’t sit around talking shop but just chat and laugh because he makes such fun of himself. It makes a great atmosphere, an intensely creative atmosphere somehow.”

Sequences concluded in Salamanca, the unit returned to the Madrid area, shooting first in the Prado Museum, and then traveling to the small town of Talamanca for important tavern sequences, each occurring in the film’s different periods.

“I am very lucky because Milos wanted a Spanish director of photography for this film,” says DP Javier Aguirresarobe. “He believed Goya’s visual universe could be better understood by a cinematographer from the painter’s own country. For me it was incredible, a real dream to have the opportunity to work on a film with a director I admired since his earliest movies in Czechoslovakia.

“Milos was a great friend during the shoot and placed his trust in me. During prep I asked him how he visualized the photography for the film, and what were the most important visual references that could help us achieve an aesthetic approach. He answered that what interested him was the color of the actor’s faces and that the negative be well-exposed. “’I want black to be black,’ he said.

For his approach, Aguirresarboe says, “I realized that the photographic treatment in the film would have to take into account the tonalities achieved by classic painters. Goya’s Ghosts is not a film of garish colors but one with believable light and expression. I started studying classic masters, the best period of Spanish painters, Ribera, for example who is one of my favorites, and began to load my imagination with the visual spirit of warm light, slightly warm tone and dark densities.”

Shooting the film entirely on location presented challenges for Aguirresarobe, not so much in terms of lighting but of logistics. “The whole movie was filmed in natural settings, many interiors, locations that are extraordinary and authentic. There is not a single shot done in a studio. A serious inconvenience had to do with the locations – the grand palaces – that belonged to the Spanish National Heritage. In these buildings we were carefully watched by Patrimonio authorities so that no piece of equipment came close to brushing against the walls in rooms that have been decorated and preserved for over 250 years.

“To resolve the difficulty we made structures that were hidden behind curtains, and they supported the lights. In that way I was able to create interesting light in these areas which are usually open for tourists.”

According to Forman, “Javier Aguirresarobe did an incredible job. The funny thing is that we don’t speak the same language. He speaks Spanish and French but not English. We communicated in French. I think it worked because he could pretend to understand me and then do whatever his heart desired.”

After finishing in Talamanca, the unit set up for two weeks in the town of Boadilla where two major sequences were shot at the town’s Royal Palace: inside– the elegant, formal interiors of the home of the prosperous merchant Bilbautua and his family; outside–the palace courtyard standing in as a section of Madrid’s famous Plaza Mayor in which a public execution takes place during the climax of the film.

The Royal Palace at Boadilla had been standing derelict for years when the filmmakers discovered it and decided to renovate for their purposes. “Madrid’s Plaza Mayor is a magnificent space which would take 15,000 people to fill,” Von Brandenstein says. “So we had to look for another square for the scene, and even considered using the Plaza Mayor in the town of Salamanca where we were also filming. But to close down the square and compensate its many merchants would have cost as much as building our own period Plaza Mayor in Madrid.

“Milos is such an experienced director, however, that when he saw the land in front of Boadilla Palace, he knew at once that we would be able transform it into Plaza Mayor, circa 1809. The basic architecture of the Boadilla Palace matched the style and format of the architecture of Madrid’s Plaza Mayor at the time of our story. Milos saw it would be possible to add on to the existing structure, to build extensions at right angles to the front of the palace that enclose the area in front so that suddenly you have the sense you were in a public square.

“We contacted the Historical Association and told them we wanted to re-facade the front of the palace and they agreed. We worked with a local company and the results were wonderful. Then of course we went inside and re-did the interiors for the Bilbatua house, recreating the world of the late 18th century with fabrics, reproductions of Goya’s paintings, marble work, masonry and intricately patterned wallpaper.

“We even had two young painters, Colt Hausman and TK, who worked in the art department, paint frescoes on the ceiling of the entrance stairway that were copies of frescoes that had been painted on the ceiling of several Spanish chapels. It was a marvelous project. And we were all delighted with the quality of the Spanish craftsmanship.”

Filmed inside Boadilla palace were scenes with Ines and her family after she’s been called to present herself at Inquisition offices, and the tension-filled, formal dinner Goya and Lorenzo attend during which the family tries to find out about the whereabouts and condition of their absent daughter.

In these scenes, costumes as well as décor reflect the elegant world of the Bilbatua family. Oscar-winning costume designer Yvonne Blake, a creative and accomplished artist, took her cue from Forman in creating the clothes.

“Essentially what I wanted to do was to get everything right. Understanding Milos’s approach, I knew it meant studying Goya’s work. Really, it’s all there. Everything’s in Goya’s paintings and you don’t have to look much further.

“A few years ago I designed an opera, Rossini’s Barber of Seville which I decided to do in Goya-esque costumes because I feel Goya loved costumes. He dressed well. He loved clothes. I love the way he treats colors and textures in his paintings and we try to re-create that here. More than re-create. In some ways it’s out and out copy. I’d say fifty-fifty the costumes come from the paintings and things we just created. The Queen’s costume is an absolute copy.

“Some costumes are composites, however. There’s a painting by Goya of a minister, Juan Antonio Llorente, from 1810 that made a big impression on Milos. He liked that image for Lorenzo. When I saw the painting I did a mixture. I created a similar high churchman’s costume with a wide ribbon or sash that featured a medal attached to it as in the painting. That particular medal was wrong for our period, it was from a later era. I designed an Inquisition cross for Lorenzo to wear, a badge, not a medal, and it worked.

“For the fictional characters that Natalie plays, Ines and Alicia, I created all the costumes from scratch. I tried to invent based on what I thought Goya would have done. All the characters go through huge changes in their lives and of course the costumes reflect that. Ines’s changes are radical. She starts out as a wealthy young woman, beautifully dressed, elegant. In the end she’s in little but rags. As Alicia, Natalie really wears only one signature costume, very Spanish and it identifies her as a young Spanish woman whose charms are for sale.

“Goya, too, wears elegant clothes at the beginning of the film. He’s a bit of a fop. Later on, having been ill and becoming deaf, he stopped paying attention to how he looked and that was something I wanted to reflect in the costumes.

“Milos and I had a talk about the two halves of the film, if you will, because there’s a sixteen year break in the action. I suggested to Milos in general that we use rich colors in the first half of the film. For the second half where things are, if not more somber they deal with some of the characters in reduced circumstances, I thought that we could try to draw some color out of the film.”

Forman is indebted to his collaborators. “The costumes are outstanding. They come directly from Goya but they’re not really costumes. They’re the clothes people wore. They’re real. It’s the same with the sets. We built some sets and shot in real places, real castles, even an actual room that was once Franco’s office. But it’s impossible to tell what’s real and what’s built for the film. Everything looks just as it is supposed to. Goya would have been comfortable there.”

After shooting the scenes inside the Bilbatua household and then the public execution of a so-called heretic, a last-gasp auto-da-fe, in the recreated Plaza Mayor, production wrapped on December 9, 2005 after 14 weeks of filming.

Production notes provided by Samuel Goldwyn Films.

Goya’s Ghosts

Starring: Javier Bardem, Natalie Portman, Stellan Skarsgård, Randy Quaid, Jose Luis Gomez

Directed by: Milos Forman

Screenplay by: Jean-Claude Carrière, Milos Forman

Release Date: July 20th, 2007

MPAA Rating: R for violence, disturbing images, some sexual content and nudity.

Studio: Samuel Goldwyn Films

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $1,000,626 (11.8%)

Foreign: $7,443,885 (88.2%)

Total: $8,444,511 (Worldwide)