A stiff drink. A little mascara. A lot of nerve. Who said they couldn’t bring down the Soviet empire.

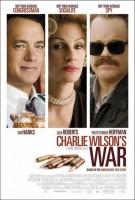

Charlie Wilson’s War is the outrageous true story of how one congressman who loved a good time, one Houston socialite who loved a good cause and one CIA agent who loved a good fight conspired to bring about the largest covert operation in history.

Oscar winners Tom Hanks (Forrest Gump, Philadelphia), Julia Roberts (Erin Brockovich, Closer) and Philip Seymour Hoffman (Capote, The Savages) team with Academy Award-winning director Mike Nichols (Closer, The Graduate) and Emmy Award-winning screenwriter Aaron Sorkin (A Few Good Men, The West Wing) to bring George Crile’s best-selling book to the screen.

Charlie Wilson (Tom Hanks) was a bachelor congressman from Texas whose “Good Time Charlie” personality masked an astute political mind, deep sense of patriotism and compassion for the underdog. In the early 1980s, with the looming advance of a Russian invasion, that underdog was Afghanistan.

Charlie’s longtime friend, frequent patron and sometime lover was Joanne Herring (Roberts), one of the wealthiest women in Texas and a virulent anticommunist. Believing the American response to the invasion of Afghanistan was anemic at best, she prodded Charlie into doing for the Mujahideen-the country’s legendary freedom fighters-what no one else could: secure funding and weapons to eradicate Soviet aggressors from their land. Charlie’s partner in this uphill endeavor was CIA agent Gust Avrakotos (Hoffman), a bulldog, blue-collar operative who worked in the company of Ivy League blue bloods dismissive of his talents.

Together, Charlie, Joanne and Gust traveled the world to form an unlikely alliance among Pakistanis, Israelis, Egyptians, lawmakers and a belly dancer. Their success was remarkable. Over the nine-year course of the occupation of Afghanistan, United States funding for covert operations against the Soviets went from $5 million to $1 billion annually, and the Red Army subsequently retreated from Afghanistan.

Capturing Charlie on Page: Background of the Film

By 1979, Congressman Charlie Wilson had, in peerless fashion, represented Texas’ 2nd District for six years. “The liberal from Lufkin” was a paradox who routinely championed the disempowered. He battled for women’s rights and seniors’ tax exemptions, but the native Texan also opposed gun control. His black constituents were his biggest supporters; he was pro-choice in the Bible Belt. His district loved him.

On Capitol Hill, Wilson was perhaps better known for the personal foibles that accompanied his growing political capital. He surrounded himself with a bevy of beautiful assistants, dubbed, naturally, “The Angels.” With his 6’4” frame, booming voice, quick wit and infinite charm, he had a way with the ladies helped by a love of the whiskey. Scandal seemed to follow him everywhere, but as he was so affable, Wilson always managed to dodge any damage. And of all the events occurring in 1979, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan seemed least likely to appear on his radar. Then again, nothing Wilson did could ever be described as likely.

The public revelation of Wilson’s extraordinary exploits began with a 60 Minutes profile produced by award-winning journalist George Crile in 1988. Crile continued to follow the story and wrote a best-selling book about Wilson’s covert war that read like a novel, except it wasn’t fiction. As Crile noted in his book, “It was January of 1989, just as the Red Army was preparing to withdraw its soldiers from Afghanistan, when Charlie Wilson called to invite me to join him on a fact-finding tour of the Middle East. I had produced a 60 Minutes profile of Wilson several months earlier and had no intention of digging further into his role in the Afghan war. But I quickly accepted the invitation. The trip began in Kuwait, moved to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, and then to Saudi Arabia-a grand tour that took us all to three of the countries that would soon take center stage in the Gulf War. For me, the trip was just the beginning of a decade-long odyssey.”

Wilson’s outrageous tale of international intrigue and global politicking, cast with colorful characters who dreamed of glory, captivated the veteran reporter. It also proved to be an extraordinary challenge to document the confounding saga of Muslim fundamentalists, Jewish arms dealers and CIA agents working in tandem with two Texans and a Greek-American CIA agent.

Crile’s wife, publisher Susan Lyne, explains: “No one involved knew the whole story. Charlie knew his part; Gust his, Joanne hers. George interviewed Charlie and Gust many times over many years and as they learned to trust him, they gave up a little more each time. George had to put all the pieces together and then find a narrative arc that would invest the reader in the characters and the outcome.”

Obtaining and deciphering the material was a monumental task, especially since Crile never quit his day job. “The time it took seems ridiculous [13 years from that first trip to publication], but he was unraveling secret deals with countries that don’t even acknowledge each other, CIA covert ops and the inner workings of congressional committees,” Lyne recalls.

Her sister, Barbara, became Crile’s cheerleader and sometime gadfly-supporting, editing and otherwise urging him to finish the book. She was so instrumental to his process that he dedicated the book to her.

“I think what intrigued him was that this was such an American story, with fallible characters who-underneath the gruffness and drinking and womanizing-had dreams of glory,” Barbara Lyne explains. “They responded to these underdogs, the Afghan Mujahideen, and believed they could make a difference in the world. Lots of people have dreams of glory, but, occasionally, the stars align just right and three or four people come together and something huge blossoms. George loved redemption stories, and loved this one particularly, because the heroes were so unlikely. He liked the fact that, as the Afghans would tell you, `Allah works in mysterious ways.’ The Americans who participated were all outsiders and misfits who didn’t belong in this arena, but they took risks and guessed right.”

When Crile’s book finally debuted in 2003, it became a best seller and attracted attention from Hollywood. Producer Gary Goetzman first heard of the book through a Washington connection. “A congressman whom I am very fond of told me about Charlie Wilson and what a fascinating character he was,” Goetzman recalls.

Goetzman and his producing partner, Tom Hanks, did just that. Upon reading “Charlie Wilson’s War,” they became fascinated with the rollicking tale, especially the inner workings of D.C. and the Afghan resistance to the Russian Army documented by Crile. “It was a great political story that was also wildly entertaining and absolutely unique,” Goetzman says. “Charlie was so impressed by what these Mujahideen went through to get the Soviet Union out of their country. The way he went about helping was outrageous, mesmerizing and funny.”

“We took one look at that book and pounced on it,” Hanks adds. “It read like a house on fire.” The actor / producer was most dumbfounded by the fact that, “like every other American, I thought it was a great thing that this ragtag group of Afghans defeated the Russian Army. I thought it was a miracle and it took a long time; what a brave bunch of patriots they were. I had no idea about the covert aspects, or that the money was coming in from the United States and other countries to arm them-money out of our own Congress, signed off by the White House.”

After Goetzman and Hanks won over Crile, the task of translating his tome into a screenplay went to Emmy Award-winning writer Aaron Sorkin, known for political stories full of intelligent characters, witty wordplay and engaging plots. From A Few Good Men (the play and the film) to The American President and the highly regarded series The West Wing, Sorkin has deftly navigated the echelons of American power, from the military to the Beltway-the stomping grounds of Wilson.

“I read a review of the book, and I went out and bought it,” remembers Sorkin. I’d read the first 50 pages when I saw in the trades that Playtone had bought the film rights. I asked my agent if he could get me a meeting with Gary Goetzman so that I could try to convince him that I might be the right screenwriter to adapt it.” He adds, “Gary, in a rare display of poor judgment, hired me.”

Sorkin’s next challenge was to distill Crile’s intricately detailed book into a script. To find just the tone, the writer would spend months researching the world Crile had meticulously documented. “It took me about eight months to complete a first draft,” he states. “The book is essentially a series of very detailed, in-depth interviews, and it doesn’t immediately present itself as a movie. Screenplays are usually written in three acts, but, after a lot of climbing the walls, a five-act structure came to me.”

The screenwriter met with Crile several times during this process, and the journalist made his research available to Sorkin. In preparation, Sorkin also spent time with Wilson, who would become a regular contributor throughout the production. Wilson proved to be every bit the gentleman and frequently offered his sharp intellect, wicked sense of humor and keen knowledge of history.

The congressman was open to Sorkin’s interpretation: “Anybody who reads a script about himself for the first time will have some reservations; you think that some of your most heroic deeds have been left out,” Wilson says. “But you grow to realize that only so much can be put in, that no movie can have all of the scenes that a book or even a life does. I accepted that early on.”

Commends Goetzman: “From the first day I talked to Charlie on the phone, I thought this was the funniest, warmest, savviest straight shooter that I’d ever talked to regarding a movie. He never let us down, solid as a rock-always there understanding the process more than he should.”

The producers worked with Sorkin to translate Crile’s story into screenplay form, while honoring the basic truths of what Charlie, Joanne and Gust accomplished. “That’s the trick,” offers Hanks. “You’re not going to be able to get the kitchen sink. Charlie Wilson’s War could be a fascinating documentary. But, as a piece of entertainment with historical aspects that are going to be interpreted, you get an artistic aesthetic that requires perspective. All that is drawn from the book and includes conclusions from the entire creative team, but it started with Aaron’s screenplay and matches up to the sensibility of George’s book.”

When Playtone and Sorkin were satisfied with the draft, the producers approached filmmaker Mike Nichols about directing the project. Nichols, whose career spans more than four decades of stage, screen and television, has explored the lives and loves of a variety of memorable characters, revealing them through humor, intelligence and sensitivity. “We felt that this was the kind of material that might attract Mike,” notes Goetzman. “Political intrigue, coupled with a character like Charlie, whose exploits were not just astonishing, but always entertaining. Charlie and his partner-in-crime, Gust, were great foils, completely different personalities; together they are smart and funny, unbelievably captivating…Joanne Herring, who was glamorous, sexy and stubbornly single-minded-all that makes for great human drama. And comedy often comes out of the most singular and mind-boggling circumstances-the kind of material made for Mike.”

Longtime friends Nichols and Hanks had come close to doing a picture together, but nothing came to fruition until Charlie Wilson’s War. The double Oscar winner commends he’s been influenced by his director’s work since his early acting days. “I know where I was and what I was going through when I saw Mike’s films, from Catch-22 to The Graduate to Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” reflects Hanks

For Nichols, the project began with a simple discussion. “Tom and Gary wanted me to read the book,” he says. “Of course, I loved the book and was very interested. The idea of Aaron Sorkin seemed to be brilliant and correct. Tom and I were good friends, and I always wanted to work with him. And then, of course, he was better than I could have imagined.”

The director next met with Wilson, and he was mesmerized by the statesman. “He owns the room, and he is the only politician I’ve met who isn’t at least partly prerecorded,” Nichols states. “He listens to you, and he answers with whatever comes into his head. He’s courtly and kind and thoughtful; he truly loves people.”

Not only Wilson’s self-effacing, bold honesty, but also his story of “three people who brought down a giant empire” impressed the director. Nichols clarifies, “They had a lot of open help from the people whom they inflamed. But, basically, among the three of them, they got the things started that caused the fall of the Soviet Empire.

“A lot of people don’t know how serious the Cold War was, how terrified everyone was of Russia, how it was a fact,” Nichols continues. “It wasn’t a guess about weapons of mass destruction; they had them. The Cuban Missile Crisis was sheer terror, because the Russians could have unleashed them on us. As Charlie says, these things really happened, and it’s very hard to grasp that there was one bad guy and it was Russia. All over the world, everybody was terrified of them.”

To prepare for the role, Hanks huddled with Wilson (who would prove an invaluable consultant on the project) to discuss everything from politics, Herring and Avrakotos to his often outrageous personality. The former congressman proved quite candid and gracious, giving very specific character notes-which seldom bathed him in a perfect light, but reflected his feats as well as his foibles.

Provides Hanks: “I said, `Okay, you’ve got a guy running against you for your seat in Congress. You’ve been investigated for doing drugs. You’re known as a ladies’ man. You’re notorious for your drinking, your carousing and your partying. What do you say in the campaign against the guy who wants to get Good Time Charlie?’ He said, `The opposition could say whatever he wanted to say about me, but we passed more Medicare bills, we took care of our veterans better than anyone else, we brought home this bill and that bill.’ He was the consummate politician, but he was never hypocritical about his behavior. Plus, he is an impressive physical specimen. He’s very tall; he’s got a massive voice, all that Texas stuff-from the cowboy boots to the belt buckles and suspenders-and he’s also incredibly charming.”

Continues Hanks, “He had already invested a lot of time and heart into the book with George. On some level, he was accustomed to another person asking him about the finer points of his life. What was amazing, to Charlie’s credit, was that he said, `I don’t care what you say about me. Show me doing anything you want to because, chances are, I did it. It’s the historical record that I want to be dealt with accurately.’ He took us to task about that over and over, but he didn’t care if we showed him in a hot tub in Las Vegas with a bunch of exotic dancers…because he did it.”

Sadly, author George Crile did not live to see the film begin production. He died of pancreatic cancer on May 15, 2006, at age 61. “We lost George Crile before we started shooting,” reflects Goetzman. “His writing the book, his love of Charlie was such a big part of his life, and one of the greatest things for him was this movie getting made. To lose him before shooting was really tough.”

Big-Haired Texans and Angry Spies: Casting the Production

Charlie Wilson’s War marks the second occasion Nichols has worked with Julia Roberts and Philip Seymour Hoffman, and he was thrilled to reunite with them. Of his interest in bringing on Roberts for the project, the director comments, ““Julia is so shockingly creative. She is a wonderful screen actor, a joy to work with, as good as it gets. Her ingenuity about costumes and makeup and what the person would and wouldn’t do…she is really remarkable. We knew the character was somewhat older than Julia, born-again, a Texas millionaire who’s had numerous husbands. Every second Julia’s on the screen, she is so electric, surprising and somehow compelling-even though the character is apparently way held back, very controlled. You see someone you’ve never seen before, and that’s very exciting.”

Roberts admits that Herring is unlike any character she’s portrayed. “I don’t know that I would have envisioned myself in a part like this, but I love that Mike wanted me for it. It is such a fabulous script; it is so much juicier and has much more depth than the usual screenplay. And Joanne is such a fantastic character, so energetic and yet so enigmatic. She is really a contrast study in every way-a beautiful socialite who also is zealously interested in the plight of these Afghan fighters.”

Whereas Hanks spent time with Wilson in advance of playing him, Roberts elected not to meet with Herring until she’d determined her character. This was no slight against Herring, but rather an artistic decision. “It’s funny to play a real person; there’s a fine line between imitating and interpreting who that person is,” she offers. “I was torn and felt that way when I did Erin Brockovich. It’s tricky to know when the right time to meet is. So I read all the research materials I could get my hands on and watched footage, the 60 Minutes piece on Charlie, and a couple things that were about Joanne. When I finally did meet her, she was just lovely-with fine social graces, dressed impeccably.”

Nichols understood Roberts’ decision to create a character uninfluenced by the person upon whom her role is based. He notes that, while the protagonists in Charlie Wilson’s War are based on real people and real events, ultimately, they must behave as characters in a movie and adhere to the demands of the story. For audiences-and for Nichols-the hope is that the characters become real people.

For the director, it boils down to “obligation to the scene and the story you are making. A character is a character; most are based on someone at sometime. It goes from as specific as Karen Silkwood to as metaphoric as Mrs. Robinson, but both are real people. And the actor and I approach it in the same way: Who is this? How do they live? What do they wear? Whom do they love? You can’t show everything that happened, but you can be faithful to the events-to the acts that were performed, the things that they said.”

Though Roberts was reuniting with Nichols and his team, this was the first time she and Hanks had worked together. She observes, “Mike always has a core group of people that are with him. There is a familiarity and security there that is just a joy. And then there’s Tom Hanks, who is as sweet, energetic, funny, kind and amazing as I ever dreamed him to be.”

Philip Seymour Hoffman, who plays the shrewd, hotheaded CIA agent Gust Avrakotos, never met the man he was portraying; Avrakotos died before the film began production. But by all accounts, the actor eerily channeled him. Indeed, Nichols marveled at Hoffman’s transformation into the spy. “Phil Hoffman and I worked together on The Seagull, and he was astonishing. Every 50 years, there is a great actor of that kind,” Nichols says. “He comes out playing whomever he is playing-whether heartbreaking or terrifying or overwhelming-that makes you have very strong emotions. My guess is that Gust was intimidating; anybody who kills people that we don’t even know about is intimidating. I kept looking at Phil, thinking, `Are you sure this is the same guy who played Capote? That small, slender reed?’ Because here is a bull, and I couldn’t put the two together. The truth is he can be anyone he wants to be.”

The actor relished the challenge of portraying the spy. Hoffman became intense-and often explosive-when he spoke in character and felt comfortable tapping into Avrakotos’ persona with his director’s guidance. “I’ve known Mike for about seven years now,” Hoffman provides. “We did a play together back in 2001, but I met him in 2000. He’s become a friend, someone I love. Working on the play with him, and now working on the film-it’s been this great road to getting a sense of each other.”

The confessed news junkie notes that while the themes of the film appealed to him, it was the characters and their escapades that hooked him. “I’ve become addicted to news, so it was great to look at what is happening in our country and in the world now through the things that Charlie and Gust did, because they are so linked up,” Hoffman says. “But, ultimately, it was the characters and their story. There’s nothing we had to do to make them seem more interesting, and it was fascinating to explore them.”

Hoffman grew to know Avrakotos through the people who understood the man best. He spent time with both the agent’s son and retired operative Milt Bearden, the film’s CIA technical advisor who took command over Avrakotos’ “Afghan station” after Avrakotos and Wilson had the covert Mujahideen Army and training camp running like a factory. Both Wilson and Bearden marveled at seeing their dear friend come to life through Hoffman’s portrayal. Recalls Hoffman, “Charlie said, `You and Gust would have loved each other,’ and I have a feeling that’s true.”

The experience of watching his old mates/conspirators cast as Oscar winners was a bit surreal for the retired statesman. Of Hoffman playing Avrakotos, he states, “Gust was a street fighter, a tough guy who made his living that way-big and muscular and menacing-and Hoffman was all of those things. He has Gust’s lethal, ominous air and intensity; with the dark glasses and the mustache, he looks a lot like him. It’s almost evil that Gust and George couldn’t have been around to see it.”

Of his Joanne, he continues, “Of course, I knew that Miss Roberts was an amazing actress, but there was one scene in particular, a party at Joanne’s mansion, when Julia made her entrance-it was just electric. It was the first time I’d seen her with Tom, and their chemistry was remarkable.”

With all the real-life characters in Sorkin’s screenplay, only one major player was a composite of several real people. That was Bonnie Bach, Wilson’s administrative assistant and gal Friday. When casting the role, Nichols recalled a small film that launched the career of Oscar-nominated actress Amy Adams. He states, “I fell in love with Amy when I saw Junebug; she just amazed me, and I made everyone go see it. I followed everything she did, and working with her was pure joy.”

Adams says, “I met with Mike and came out for one of the table reads in New York. After that, they approached me about playing Bonnie. I loved the script; I thought it was a great story that needed to be told, and I wanted to be a part of telling it.”

Her wonky, slightly exasperated banter with Hanks as Wilson was a source of amusement to the performer. She had appeared on several episodes of Sorkin’s The West Wing and was attuned to his clever mouthfuls of dialogue. “The dialogue was mesmerizing,” Adams recalls. “It had this super-smart, rapid-fire quality that Aaron is brilliant at, but I tried to play it realistically-which really works for Bonnie because she is very bright, intense and bold.”

Other supporting players in Charlie Wilson’s War include legendary performer Ned Beatty as Chairman Doc Long, the head of the House of Representatives’ Defense Appropriations Subcommittee whom Wilson convinces to help fund the Mujahideen, and British actor Emily Blunt as Jane Liddle, the not-so-conservative daughter of one of his district’s most conservative men.

Blunt had recently completed the film The Great Buck Howard, opposite Tom Hanks’ son Colin, and was eager to work on Charlie Wilson’s War. “Mike had seen a film that I’d done and wanted to meet with me,” remarks Blunt. “I didn’t know what the part was, just the prospect of working with him was very exciting. And the script was such a funny read-dense and thoughtful, but with a wonderful, underhanded tone to it.”

In life and in the film, Charlie made a beeline toward the smoldering and receptive Jane Liddle, a character that Blunt describes as someone who “appears to be demure and tries to hold any sexuality in check in front of her father, but not when she is around Charlie. She is smart and sexy and shamelessly knows what she wants. Like Charlie, she wants no commitment; she just wants to have fun.”

The famous Indian performer Om Puri plays Pakistani President Zia ul-Haq, the ruler who helps Wilson, Herring and Avrakotos orchestrate their secret war. He has appeared in another Nichols film-opposite Jack Nicholson and Michelle Pfeiffer in 1994’s Wolf. Of his role, the actor comments, “I come from north of Punjab, which is actually very close to Pakistan. Zia ul-Haq also happened to be Punjabi, except that he was a Muslim and I am a Hindu.” Of his director, he commends, “He quietly, in a very relaxed manner, gets the best out of you as an actor.”

Other key cast members include Ken Stott as Zvi Rafiah, an Israeli arms dealer who owes Wilson a couple of big favors, and Jud Tylor as Crystal Lee, an aspiring starlet from Texas’ 2nd District who dreams of life as an actress/slash/model.

Morocco to Los Angeles: Locations and Filming

Charlie Wilson’s War began principal photography in Morocco, which doubled as the countries of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Jere Van Dyk, a consulting authority on Afghanistan, and Milt Bearden, the CIA chief in Pakistan from 1986 until the Soviet withdrawal from the country, were on hand to make sure the production authentically re-created the details. In 1981, Van Dyk snuck into the impoverished country, lived with the Mujahideen and wrote about his experiences with the Soviet attacks for The New York Times, eventually penning a book about them.

Operative Bearden, as Crile pointed out in “Charlie Wilson’s War,” was personally recruited by Avrakotos to take over the Islamabad station, and he proved “devilishly effective during his three years” in his part in the covert Afghan operation. “Milt Bearden was not the kind of man that Avrakotos was going to be able to push around,” recounted the author, “and Gust wanted it that way. Bearden was a Texan, a great storyteller, a natural salesman and a very tough customer.”

The scenes that unfolded in the Atlas Mountains, where the production re-created the Afghan refugee camps, impressed both Van Dyk and Bearden. On a steep rise above the base camp that housed trailers, support vehicles, wardrobe and catering structures sprawled a motley collection of tattered tents-makeshift cooking areas that fed Moroccan extras in traditional Afghan garb crossed with 1980s attire.

“When we filmed the refugee camp, when I saw all those people-the children coming down the pass-it was 100 percent what it was like in Afghanistan,” Van Dyk says. “It was truly wonderful, the way the families looked. The whole setup was exactly what it was like in the early 1980s.”

The filmmakers’ desire for minute accuracy especially impacted Bearden. Even when not on set, he received calls from Nichols and team about anything and everything-a questionable piece of vernacular, the way a rifle was held, the type of kurta (Afghan blouse) or karakul (stiff, woolen hat) that might be worn by a native.

This quest for authenticity was quite critical to the refugee camp scene filmed high in the Atlas Mountains. Bearden explains: “Afghanistan, more than anything else, defined Charlie Wilson. When he got hold of it, he never let go until the Soviets marched across the Friendship Bridge and crossed the Oxus River.”

The mountain was so high that when clouds rolled in, the company found itself engulfed in a viscous cumulous mist. A bit of a microclimate, the area had weather that was mercurial at best; within a half an hour, a sunny, windy day was likely to give way to dark skies and rain.

The cast and crew camped at a formerly closed ski lodge, a location they grew to know well when fierce weather roared into the mountains. Shutting down production, gale force winds, giant hail, and relentless snow and sleet washed out the winding mountain pass that led to the closest big city, Marrakech, an hour and a half away. The company was stranded on the mountain, and the catering and wardrobe tents were flattened.

When the sun finally returned and the Moroccan Army had repaired the roads and deemed the area safe, the cast and crew returned to what was once the production. The art and construction departments labored to resurrect the refugee camp set, and while the new incarnation was a bit more bedraggled, that construction’s ramshackle quality was, in certain ways, even more reminiscent of the camp than the original set.

In addition to the Atlas Mountains, the film lensed in the Moroccan capital of Rabat in an ornate palace with an airy courtyard and immense arched anterooms; in the local fashion, its crumbling marble walls were intricately tiled. Once at the location, the cast and crewmembers could not venture far. During filming, the king met with parliament, headquartered near the set. The government shut down adjacent streets for the day, but as filming wrapped, so did the king’s business-allowing everyday life to return to the city.

When the company moved to Los Angeles, one of the impressive scenes shot in the city was the soiree at which Herring first charms Wilson and enlists him in her cause to help the Afghan refugees. It was lensed at the onetime Chandler Estate in Hancock Park, built in 1913. The six-bedroom, seven-bath Beaux Arts residence is nearly 10,000 square feet and features a pool, gourmet kitchen, music room and library, among its many amenities. The garage is so large it was possible to house the craft service that serviced night shoots.

To create the festive setting of Herring’s charity auction, production designer Victor Kempster covered the pool, propped up an Afghan-style façade-the type that might affectionately be interpreted by a Houston socialite with a cause-and festooned the area with lanterns.

On the Paramount Pictures backlot, Kempster designed a debauched Las Vegas hotel suite, with a giant hot tub and panoramic “view” of the Strip that visual effects supervisor Richard Edlund would create. Black, gold, mirror and crystal-with Greco-Roman motifs-the design embodied Vegas as the heyday Sin City.

Kempster’s team also re-created a more dignified locale: the halls of Congress. His crew was allowed to photograph and analyze blueprints and measure the actual congressional corridors, but the fabled Speaker’s Lobby outside the House floor was off limits. They would end up building it to scale and fitting the area with wild walls so that the camera could move about freely. To put in perspective, the corridor was large enough to accommodate a Technocrane without disturbing the ornate carpets or the chandeliers.

Wilson particularly enjoyed the reincarnation of his old Washington haunts, with his office and bachelor pad apartment reborn on a soundstage. “That reconstruction of the Speaker’s Lobby was the most amazing damn thing in the movie. It’s among the Seven Wonders of the World,” he says. “I just don’t know how they did it, got the tile floors, the portraits of all the former speakers on the wall-spectacular!”

To shoot these exotic locations, Nichols would turn to another old friend. Charlie Wilson’s War marks cinematographer Stephen Goldblatt’s third collaboration with the director. Too, Wilson’s incredible life provided a welcome new canvas for the DP. Goldblatt was among several returning Mike Nichols alumni, who combined with Playtone regulars such as production designer Kempster and his art department.

Their work was as true to the narrative and the period as possible, but in the end, as Nichols notes, “Ideally, you’ll forget that there was a camera and film and lights and art director and makeup people. You’re supposed to fall into it and experience it as life. If you’re lucky, the events and the story burn away the technique.”

Shoulder Pads and Cowboy Boots: Costumes of the Film

The sequences of Charlie Wilson’s War Nichols filmed in the Atlas Mountains required up to 900 extras at a time and proved especially challenging for double Oscar-winning costume designer Albert Wolsky and team. The production prepped and shot in the Muslim country during the holy season of Ramadan, and Wolsky needed to have everything in place in advance of the fasting days. “We hired a costume supervisor just for that portion, and we sent him two months before; at the same time, we had people working in Afghanistan and Pakistan.”

Wolsky adds that the refugee wardrobe needed to have a certain drab color palette, which required vigilance to maintain until the cameras rolled. “Of course, we couldn’t use all real things that people had worn, but our Afghan liaison arranged to work with second-hand clothing vendors in Kabul, and all that was sent to Morocco.” Dyers and agers assisted in coloring, and any new clothes were given a patina appropriate for the era and region.

The costume design and art departments did vast research, but found that creating for Texas and Washington, D.C. in the early ’80s was more challenging than might be expected. “Doing a true period piece-and by that I mean 50 years ago or more-you can set it fairly accurately,” Wolsky notes. “But doing something that people have memories of and is so current is very tricky, especially since the ’80s fashions have made a bit of a comeback.”

From the shoulder pads for Amy Adams’ Bonnie Bach to the high coifs of Charlie’s Angels, the design, makeup and hair teams had ample opportunity to revisit the 1980s. For Amy Adams, it was a bona fide introduction to the era. According to designer Wolsky: “Amy Adams came in a modern young woman with hazy ideas about the 1980s. We started experimenting, and she came to love it. By the end of the session, she realized that it was a flattering period; the shoulder pads were for a very good reason-they made the waist look small. The Dynasty version wasn’t real life, it was already a costume-an exaggerated interpretation of reality.”

Though plainspoken in life, Wilson’s singular style of dressing was anything but simple. Notes Wolsky: “I was pleasantly surprised that I could get very close to the real Charlie Wilson with Tom,” he recalls. “Somehow it worked on him; I even borrowed one of Charlie’s shirts as a template. He wore a certain kind of collar, he loved the epaulets, the suspenders-that’s all Charlie.” Additionally, it helped Hanks’ swagger to walk in the types of cowboy boots Wilson was partial to wearing.

The designer had previously worked with Julia Roberts on Runaway Bride and The Pelican Brief and concocted a wardrobe for her Joanne Herring that was elegant, sophisticated and mostly ebony-hued. Wolsky didn’t want her to look as if she were a caricature of a wealthy Houston society woman, and ended up dressing Roberts in elegant tones of black that the designer felt provided glamorous contrast to Herring’s trademark blonde hair.

Befitting a woman of Herring’s station, Roberts wore some serious, eye-popping diamonds from Cartier North America. During filming, she donned glittery necklaces and bracelets, as well as almost 10-carat diamond earrings retailing for approximately $1.5 million and a 15-carat diamond ring worth approximately $2 million. Naturally, two armed guards appeared on set every time the baubles did.

The effect impressed Roberts. The actor notes, “The first day that we did tests, I was floored with what they could really achieve in making me look significantly different than I had when I came strolling on set with my ponytail and sweatpants.”

Production designer Victor Kempster’s team played with the chic, iconic look developed for Roberts by creating a huge full-length portrait of her as Herring, which hung in the ornate mansion set in Los Angeles. Roberts as Herring posed in a low-cut black evening gown, similar in style and attitude to the muse of John Singer Sargent’s painting “Madame X.” In this setting, the actress wore a show-stopping dress-an architectural, satin, off-the-shoulder number that was “simple and tasteful and contrasted to the more gaudy and colorful gowns her guests wore in the party scene,” Wolsky says.

To complement Roberts’ party wardrobe, Hanks donned a white tuxedo jacket and black bow tie for the event. The outfit echoed a similar one Wilson wore in honor of his 60th birthday. As Crile documented, “Casablanca was the theme he had chosen for the event. It was his favorite movie, and he had appeared for the occasion in a white dinner jacket, specially tailored to look like the one Humphrey Bogart wore when he played the role of Rick.”

Of course, the blue-collar spy Gust Avrakotos never wore anything fancy, or obvious, by design. To aid his look, the designer comments, “The [oversized] glasses helped; the hair and the costumes evolved with him. Once we got through establishing the costumes, we both agreed he would be dressed almost invisibly; he may never have changed his clothes, and nothing really matches.”

Charlie, Joanne and Gust at War: A Detailed History

In December 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, an event much expected by the CIA. As Steve Coll wrote in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “Ghost War”: “The CIA had been watching Soviet troop deployments in and around Afghanistan since the summer, and while its analysts were divided in assessing Soviet political intentions, the CIA reported steadily and accurately about Soviet military moves. By mid-December, ominous, large-scale Soviet deployments toward the Soviet-Afghan border had been detected by U.S. intelligence. CIA director [Stansfield] Turner sent President Carter and his senior advisers a classified `Alert’ memo on December 19, warning that the Soviets had `crossed a significant threshold in their growing military involvement in Afghanistan and were sending more forces south.’ Three days later, deputy CIA director Bobby Inman called [National Security Advisor Zbigniew] Brzezinski and Defense Secretary Harold Brown to report that the CIA had no doubt that the Soviet Union intended to undertake a major military invasion of Afghanistan within 72 hours.”

As Crile illustrated in “Charlie Wilson’s War,” this invasion changed President Jimmy Carter’s philosophy toward the USSR. “It radicalized him,” the journalist observed. “It made him suddenly believe that the Soviets might truly be evil, and the only way to deal with them was with force.”

Crile continued in his book: “`I don’t know if fear is the right word to describe our reaction,’ recalls Carter’s vice-president, Walter Mondale. `But what unnerved everyone was the suspicion that [Soviet president] Brezhnev’s inner circle might not be rational. They must have known the invasion would poison everything dealing with the West-from SALT [Strategic Arms Limitation Talks] to the deployment of weapons in Western Europe.’”

Overt force was not a first option for the administration. This was the Cold War after all, and the two superpowers each sat upon an enormous arsenal of nuclear weapons, ominous enough to easily conjure up World War III. Too, after the wrenching turmoil of Vietnam, America was weary of entering into another conflict in which there was no certain end date.

Carter would, however, set certain wheels in motion. He authorized a boycott of the Summer 1980 Olympic Games scheduled for Moscow, instigated an embargo on grain sales to the Soviets, fast-tracked a 1977 directive known as the Rapid Deployment Force and introduced The Carter Doctrine. Crile elaborated, “The Carter Doctrine [committed] America to war in the event of any threat to the strategic oil fields of the Middle East. His most radical departure, however, came when he signed a series of secret legal documents, known as the Presidential Findings, authorizing the Central Intelligence Agency to go into action against the Red Army.”

Thus began the agency’s covert operation to arm Afghan rebels for self-defense. The nascent scheme was modest and, as Crile suggested, tied to “the CIA’s time-honored practice never to introduce into a conflict weapons that could be traced back to the United States. And so the spy agency’s first shipment to scattered Afghan rebels-enough small arms and ammunition to equip a thousand men-consisted of weapons made by the Soviets themselves that had been stockpiled by the CIA for just such a moment.” Unfortunately for the Mujahideen, this was not an impressive cache-mostly rifles from WWI with a limited supply of ammunition with which to load the purloined weaponry.

The Afghan freedom fighters proved to be some of their own best assets. Led by chieftains and mullahs, these warriors called for jihad against the tens of thousands of Soviets who began pouring in the country. However, even with the CIA’s limited help, they were no match for the Soviet military machine. Crile pointed out in his book, “The Afghan people would suffer the kind of brutality that would later horrify the world when the Serbs began their ethnic cleansing. Soviet jets and tanks would lay waste to villages thought to be supporting guerillas. Before long, millions of Afghans-men, women and children-would begin pouring out of the country, seeking refuge in Pakistan and Iran.”

It was their plight and determination that touched Texas’ 2nd District delegate to the House of Representatives. Charlie Wilson possessed a focused interest in history and foreign affairs, as well as an abiding antipathy towards the Soviet Union. The Afghans’ spirit against the overwhelming and brutal Soviet force won his favor. Fortunately for them, he happened to sit on one of the subcommittees in the House that was at the intersection of the State Department, the Pentagon and the CIA: the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee. And after a visit from a well-heeled socialite and strident anticommunist, it would only be a matter of time before he cashed in a number of favors for the people of Afghanistan.

Wilson saw the devastating effects of the Soviet invasion firsthand when taken to Afghanistan by Houston millionaire Joanne Herring on a trip that began in a typically unorthodox fashion. “Joanne approached me about 1981,” recalls Wilson. “I had already taken notice of the Afghan war, and I had doubled the appropriation for the CIA to supply the Mujahideen with weapons, but that was only a very small step. It was something I did impulsively, just because I became angry at the atrocities that were being committed there. Nobody thought the Afghans could successfully resist the Soviet Union, but Joanne was on a personal mission. She was the honorary consul for Pakistan, but she was far more than that.

“She really had the ear of Zia, and he was interested in what she said,” Wilson continues. “She was a strong anticommunist and had been to the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, so she’d actually seen what was going on. Joanne persuaded me to go to Afghanistan and take a look myself, because she was desperately trying to get someone interested in it. She was outraged about the Soviet atrocities taking place in Afghanistan, and she was concerned about the expansion of the Soviet Union.”

Herring (now King), recounts: “What happened in that hemisphere came to the United States and to Houston. I was invited to France because I was a niece of George Washington, and the great-great-great nephew of [Marquis de] Lafayette wanted me to meet what he thought were the five greatest strategists in the world. One of them was a Pakistani, and he became the ambassador to the United States. My husband was a prominent businessman who put Enron together-not the one who destroyed it.

“This man suggested that my husband become the honorary consul of Pakistan, because he wanted to do business with him,” King continues. “My husband declined, but he suggested, Why don’t you take Joanne?,’ which was quite a strange idea for a Muslim country. He recoiled in horror at first, but he also didn’t want to offend him, so he agreed. I thought, `What can I do for this country? They desperately need money.’ So I began to work with the very poor. Our efforts were very successful. I was appointed under [Pakistan’s] President Bhutto, and later, President Zia continued to use my services because he felt that I had done a good job; then, he began to use me as an advisor.”

With Pakistani President Zia’s permission, Herring began producing a documentary that outlined the plight of refugees from Afghanistan into Pakistan-even traveling to the secret enclaves of the Mujahideen with the film’s director, Charles Fawcett. Her mission was to show the film and raise funds and awareness in America for the refugees’ plight.

Pulling her own favors, Herring called Zia in advance of Wilson’s trip and recommended him, with the proviso, as Crile noted, “that he not be put off by Wilson’s flamboyant appearance and not pay attention to any stories of [his] decadence that diplomats might relate.”

Wilson was no stranger to the culture as he had, as a seaman in the Navy, operated in the Indian Ocean with the Pakistani Navy. “President Zia was very passionate about what was happening to his fellow Muslims,” the former congressman explains. “I could tell that he was a very fearless man. He arranged for me to have Pakistani Army helicopters and go up to the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan, very near the Khyber Pass. That was the experience that will always be seared in my memory: going through those hospitals and seeing the people, especially the children, with their hands blown off from the mines that the Soviets were dropping from helicopters.

“That was perhaps the deciding thing that made a huge difference for the next 10 or 12 years of my life,” Wilson tells. I left those hospitals determined that, as long as I had a breath in my body and was a member of Congress, that I was going to do what I could to make the Soviets pay for what they were doing, and to try to help the Afghans.”

Back in D.C., Wilson would find a kindred spirit in CIA agent Gust Avrakotos. A tough, streetwise Greek American, an anomaly in the agency then run by America’s patrician class, Avrakotos was just the man Wilson needed. As Crile wrote, “He had been recruited to be a street fighter for America, and he was proud to offer his brilliant mind and ruthless skills to the country that his father had taught him to honor above all else.”

Like Wilson, the Afghans’ spirit impressed him and, as Crile indicated, “he had taken to the Afghan program like a duck to water. There was nothing like killing communists to give him a sense of well-being.” Crile suggested, “Just like Wilson, Avrakotos had felt something stir inside him the moment he met the Afghans. They were killers, and he understood these people. They wanted revenge. He wanted revenge.”

Together, Avrakotos, Wilson and a small crew of like-minded operatives engineered an intricate plan to fund, arm and train the Mujahideen, with the help of Pakistan, Israel, Saudi Arabia and China. It didn’t hurt their mission that another CIA campaign had captured the attention of the government and the media: the Iran-Contra Affair, which was diverting much of the attention and heat that could have come Avrakotos and Wilson’s way. The partners carried on with little scrutiny.

The biggest result of their efforts was ensuring the Red Army’s march across the Freedom Bridge and out of Afghanistan in 1989. Wilson recalls that, despite the nearly impossible odds against them, the Afghan people resolutely stood up to the Soviets. He, Herring and Avrakotos saw an opportunity to fight the Soviet Union alongside them, and their plan succeeded beyond anything they could have imagined. “I was just impassioned by the resistance, and I was horrified by the obvious harsh terror tactics that the Soviets were using on these somewhat defenseless people. I dedicated myself to this cause-to increasing the amounts of money allocated to this campaign-making sure they got the right weapons and training.

“The Soviet Army was the most fearsome in the world,” Wilson continues. “It was thought to be invincible. It had terrorized the world for 50 years-the great, indomitable Red Army. And these were barefoot, illiterate tribesmen, with 303 Enfield rifles, who were successfully resisting them. It was always my thought that if we could get them something sophisticated to allow them to destroy the Soviet tanks and defend against the Soviet helicopter gunships, they conceivably could drive the Soviets from their land. Nobody believed that much except me and Gust. We made it work.”

Naturally, a covert operation is, by definition, one in which the people generating it must remain hidden in shadows. This, according to Crile, became a perilous proposition for America: “Throughout the Muslim world, the victory of the Afghans over the army of a modern superpower was seen as a transformational event. But, back home, no one seemed to be aware that something important had just taken place and that the United States had been the moving force behind it.”

****

Of all the adventures Wilson has had, having his story portrayed in film was most humbling for the septuagenarian. “Being involved with this movie is one of the real highlights of my life,” he concludes. “And I haven’t had a boring life. The whole process was mind-boggling for a country boy from Lufkin. Mike Nichols’ attention to detail was incredibly impressive, and to be on set and hear someone with the stature and talent of Tom Hanks saying my words and being called Charlie…well that’s something.”

As for the end of this chapter of Wilson’s story, Nichols muses, “Anyone who brought down the Soviet Union would remember it fondly, and he can take a bow. I think that’s allowed.”

Production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

Charlie Wilson’s War

Starring: Tom Hanks, Julia Roberts, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams, Om Puri, Jud Tylor, Nazanin Boniadi

Directed by: Mike Nichols

Screenplay by: Aaron Sorkin

Release: December 25, 2007

MPAA Rating: R for strong language, nudity/sexual content and some drug use.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $66,661,095 (56.3%)

Foreign: $51,695,112 (43.7%)

Total: $118,356,207 (Worldwide)