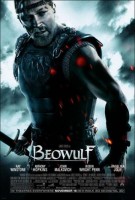

In the age of heroes comes the mightiest warrior of them all, Beowulf. After destroying the overpowering demon Grendel, he incurs the undying wrath of the beast’s ruthlessly seductive mother, who will use any means possible to ensure revenge. The ensuing epic battle resonates throughout the ages, immortalizing the name of Beowulf.

Academy Award-winning director Robert Zemeckis tells the oldest epic tale in the English language with the most modern technology, advancing the cinematic form through the magic of digitally enhanced live-action.

Unlike anything you will see this year, “Beowulf” represents a decade long quest for New York Times bestselling author Neil Gaiman (the graphic novels Mirrormask and Sandman), and Academy Award-winning screenwriter Roger Avary (“Pulp Fiction”) to see the myth adapted to the big screen. With Real D, Dolby Digital 3D and IMAX 3D “Beowulf” delivers an unparalleled immersive experience that transports you to the age of heroes.

Set in a magical era veiled by the mists of time, replete with heroes and monsters, adventure and valor, gold and glory, one exceptional man, Beowulf, emerges to save an ancient Danish kingdom from annihilation by an ungodly creature. In return, this legendary six foot-six-inch Viking, brimming with daring confidence and ambition, succeeds to the throne.

A Heroic Epic for the Ages

The name Beowulf resounds throughout the kingdom and songs are sung of his exceptional prowess and deeds after he comes to the rescue of King Hrothgar, whose kingdom has been devastated by Grendel, a ruthless monster who has tortured and devoured its residents, leaving them in a constant state of panic and fear.

In ridding the kingdom of this savage beast, Beowulf gains fame and fortune for himself. Great riches and overwhelming temptations are thrown at him. How wisely he chooses to handle his newfound power will forever define his fate as a warrior, a champion, a leader, a husband and, most importantly, as a man.

Beowulf is the oldest surviving epic poem in the English language. While Robert Zemeckis’ film adaptation contains many of the poem’s characters and themes — great monsters and heroes, the eternal conflict between good and evil, and a layered exploration of the nature of valor and glory — it is definitely not your high school teacher’s Beowulf.

“Frankly, nothing about the original poem appealed to me. I remember being assigned to read it in junior high school and not being able to understand it because it was in Old English,” admits Zemeckis. “It was one of those horrible assignments. I never really thought about it after that, never considered that it might make for an interesting story. But when I read the screenplay that Neil Gaiman and Roger Avary did, I was immediately captivated. I asked them, `What is it about this screenplay that makes this story so fascinating when the poem, to me, was so boring?’ And their answer was, `Well, let’s see, the poem was written somewhere between the 7th century and the 12th century. But the story had been told for centuries before that. The only people in the 7th century who knew how to write were monks. So, we can assume they did a lot of editing.’ Neil and Roger explored deeper into the text, looking between the lines, questioning the holes in the source material, and adding back what they theorized the monks might have edited out (or added) and why. They managed to keep the essence of the poem but made it more accessible to a modern audience and made some revolutionary discoveries along the way. This should stir some debate in academia.”

As he worked with the writers to develop the story further, Zemeckis became a student of the subject in a way that would make his junior high school teacher proud. “Once I became intrigued by the script, I went back and re-read the poem, talked to Beowulf scholars and immersed myself in the legend. Many of the themes that are in Beowulf were lifted from the Bible — a heroic man’s journey, the fight between good and evil and the price of glory. And you see that Beowulf is the foundation for all our modern heroes, from Conan to Superman to the Incredible Hulk.”

“What’s so attractive about the Beowulf legend is that it is wrapped up in this great action-adventure-mythologicalepic world with monsters and seductresses, creatures that have certainly existed, at least in our subconscious, since ancient times,” adds producer Jack Rapke.

In retrospect, Gaiman and Avary seem the perfect talents for this project. Gaiman, as his biography notes, “…is listed in the Dictionary of Literacy Biography as one of the top ten living post-modern writers and is a prolific creator of prose, poetry, film, journalism, comics, song lyrics and drama.” In particular, Gaiman is beloved by comic book fans for his DC Comics series Sandman, which won nine Will Eisner

Comic Industry Awards and three Harvey Awards; Sandman #19 took the 1991 World Fantasy Award for best short story, making it the first comic ever to win a literary award. Avary is similarly celebrated for his dark, edgy, groundbreaking screenplays and films, including his Oscar winning screenplay for “Pulp Fiction,” (shared with Quentin Tarantino), and his influential cult films as a director, the Cannes Prix très spécial winning “Killing Zoe” and the adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ novel The Rules of Attraction.

Gaiman and Avary originally began their collaboration when they decided to work together on a screenplay version of Gaiman’s Sandman. While that project never came to fruition, the two recognized that they were kindred spirits. Nevertheless, adapting the Beowulf poem for the screen proved to be a long, strange and ultimately rewarding trip for Gaiman and Avary.

“Roger and I hit it off during the Sandman process. very much liked him and the way his mind worked,” says Gaiman. “At some point, Roger mentioned to me that he’d always wanted to make Beowulf into a movie, but he’d never been able to work out a way to get from the first two acts to the third, because the structure is such that you begin with Beowulf’s fight, then fighting Grendel’s mother and then move forward 50 years when he fights the dragon. It’s not the normal three-act structure of screenplays. I suggested a few ways that it could work. There was a pause and Roger said, `When are you free?'”

Basically, Neil came up with the key operator of a unified field theory of Beowulf, which I had been working on for a decade.” says Avary. “The poem always seemed disjointed to me and, in particular, Beowulf never seemed to be the most reliable of narrators. For instance, Grendel never attacks Hrothgar; he just torments him. Why? It made me ask the simple question that for some reason no one has ever asked before: who is Grendel’s father? It really plagued me. All of Grendel’s behavior began to make sense when examined in that light. Later, Beowulf tears off Grendel’s arm and Grendel slinks off to his cave to die.

After Grendel’s mother’s retribution, Beowulf ventures into the cave, ostensibly to kill Grendel’s mother. Yet he emerges from the cave with Grendel’s head, not the head of the Mother, which is really perplexing. Beowulf says he killed Grendel’s mother, but we only have his word. Where’s the proof that he killed the mother? It became obvious to me that Beowulf had fallen prey to the same temptations I surmised had befallen Hrothgar — the temptations of a siren. He had made a pact with a demon.

“Then, in the second half of the poem,” Avary continues, “after Beowulf has become king, a dragon attacks him and his kingdom. I couldn’t figure out how this fit into everything. I was telling Neil about my theories, when he made the remarkable insight that the dragon might be Beowulf’s son — his sin comes back to haunt him. Suddenly, the two halves of the Beowulf epic, which had always seemed so disjointed, made perfect story arc sense. Had it been a snake, it would have bit me. It’s quite possible that these elements of the structure had been lost over hundreds of years of verbal telling, and further diluted by the Christian monks who added elements of Christianity when they transcribed it to the parchment we now know as MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv.”

Gaiman and Avary are not the first to notice the awkward construction of the original poem. David Wright points out in the Penguin Classics edition of Beowulf that “… the early critics and commentators of Beowulf and a good many of the later ones have been sarcastic about the clumsiness of the plot. For the poem is a bit of a rag-bag as well, stuffed with fragments from the history of Scandinavian tribes and spilling over with untidy-looking references to apparently irrelevant events and legends.”

Wright also notes that Lord of the Rings creator J.R.R. Tolkien appreciated the poem’s power. In his famous essay, Beowulf: The Monsters and Critics, Tolkien noticed, among other things, that although Beowulf is a superhero of sorts he is, in the end, human and his all-too-human traits contribute to his downfall. “He is a man and that for him and many is sufficient tragedy.”

Zemeckis saw the hero along similar lines. “Our Beowulf is a bit more flawed, more like a human hero than a god. He’s not a Thor character. He is a real person who has a lot of flaws — hubris being chief among them.”

It’s a good bet that Tolkien did not have as much fun as Gaiman and Avary did when writing about their main character. “Roger and I flew down to Mexico and he borrowed a house from a friend for a week,” says Gaiman, “a week of absolute madness. We were surrounded by translations of Beowulf, all the different ones we could find, including some with Old English on one page and the English translation on the other. We hooked up our computers and we wrote like mad. We returned home with a script, one that Bob Zemeckis read and wanted to do.”

Now, with “Beowulf,” Zemeckis was ready to take the technology to the next level. “When you do a performance capture film you have the ability to do two forms of casting, one for performance and one for likeness, which means you can actually separate what a character looks like in the film from the performer who portrays that character,” says Starkey.

“It’s one of the reasons we decided to do the film in this style; for instance, no one on the planet looks like the character Bob envisioned for Beowulf or could perform on the level Bob wanted for this film. Beowulf is bigger than life and there is no single human actor who embodies everything Bob saw in the character. So, how do you blend these two irreconcilable aspects? By casting the best actor possible and creating that look, a six-foot-six Christ-like image in the computer. The same is true with Grendel. If we were doing Grendel in a traditional film, we would have had a 12-foot puppet on set and created additional computer graphics. In this case, we could get the perfect performer, who portrayed all of Grendel’s pain and suffering but wasn’t limited by prosthetics or uncomfortable suits. If we had shot this film traditionally, we could never have done all that,” Starkey concludes.

“Because it is a mythological fable, the demand for photo reality was not as paramount as it might be,” adds producer Rapke. “Also, to replicate the conceptual visual world Bob envisioned would be almost impossible in the 2D world. Using this process gave us the opportunity to cast whoever we felt was the perfect actor for each part. So, for us, it was the best way to get over certain hurdles and do a lot of things which would have been impossible in a traditional live action format.”

Avary adds that performance capture realized the film the way he had always envisioned it and, in addition, it presented an almost limitless canvas.

“The interesting thing to me was that the performance capture process really allowed the film to be performance- based. I had always seen it as a chamber piece — it’s in court, and there’s intrigue between people with their myriad relationships. I always wanted it to be a fully formed, emotional experience. I also remember Bob saying, `C’mon, guys, do whatever you want — when Beowulf fights the dragon, let’s really have him fight the dragon.’ We weren’t restricted by anything, so Neil and I were able to write without the shackles we’d normally have on a film,” Avary notes.

Capturing Great Performances

Essentially, performance capture removed appearance, age, color, and gender from the casting equation. Zemeckis’ choice of Ray Winstone to play the lead character is the quintessential example of the freedom in casting performance capture provides. Initially, Zemeckis hadn’t thought of Winstone, but when he heard the actor’s distinctive voice he was convinced he’d found his Beowulf.

“My wife was watching Ray doing an adaptation of `Henry VIII’ on TV and I heard his voice and said, `Oh my God that sounds like Beowulf!’ I went and watched him and he had so much power and this ability to tap into the animal part of his humanity. That’s a big part of Beowulf — he has a real visceral quality. He cares only about what he can kill, what he can eat, who he can screw. Ray is an amazing, powerful actor who has the ability to tap into that primeval aspect,” Zemeckis says.

No one was more surprised than Winstone when Zemeckis approached him for the part. “I was doing Martin Scorsese’s film `The Departed’ in New York when I got the call that they were interested in seeing me for `Beowulf.’ I came to Los Angeles to meet with Bob, and I thought, I’m traveling a long way for a job interview, but I did it because I think he’s a genius. He asked what I thought of the script and I told him I thought it was the story of a man whose greed for gold, ambition, power and fame ultimately consumes him. He’s a bigger monster in many ways than any of the demons he faces. As the conversation went on, I realized that it wasn’t an audition; Bob actually wanted me to do the film, which was quite a shock to me,” Winstone recalls. The adventure elements of the script appealed to Winstone as did the opportunity to delve into a medium that was new to him. The candid Winstone is the first to say “…

I didn’t know anything about the original poem. My children tell me they know about it. But (the script) is a fantastic story and I’ve always wanted to play a Viking. The great thing about the (performance capture) technique, is that it allowed someone like me, who is 5’10” and a little on the plump side, to play a 6’6″ golden-haired Viking. The process initially sounded complicated and a little bit uncomfortable, but I am a bit of a sucker for things I think I can’t do, so I was very excited to try it,” Winstone says.

An equally important attraction for Winstone was the stellar cast of co-stars Zemeckis had assembled. “The people working in this movie are amazing — the list goes on and on. Anthony Hopkins has been one of my favorites since I was a kid, and it was such a pleasure just to watch him work. happened to work with Robin Wright Penn in London and she is a fine actress, as is Angelina Jolie, who I’d known for five years and is just fantastic. And Brendan Gleeson, my old mate, who I worked with on “Cold Mountain,” as well as Crispin Glover and John Malkovich, who are so clever and inventive. They’re such excellent actors, I knew I’d learn something on a job like this, just working with them,” says Winstone.

Zemeckis notes that performance capture, in addition to fulfilling Winstone’s wish to play a Viking, gave all his actors the luxury of performing unfettered by the demands of conventional filmmaking. “The thing I love about performance capture is that it allows the actor to give the director those magic moments, those things the actor does you never expected,” Zemeckis explains.

“You have this wide open canvas where the actor can bring whatever he or she wants to the character because you’re not under the same constraints that you’d have on a live-action film. The actors are liberated from the tyranny of a normal movie — it’s not about lighting, it’s not about setting up the camera, it’s not about the hair and make-up or costumes. It is absolute performance and great actors, like the ones in this movie, relish that. You don’t have to break up the scene to get coverage — we did wide shots and close-ups at the same time. So the actors dictate the rhythm of the scenes, which we did from beginning to end, as much as we could. It was like theater, except that it was being captured in 3D.”

Anthony Hopkins, who plays King Hrothgar, notes that the performance capture technique coupled with Zemeckis’ directing style made for an open, laid-back atmosphere that aided the creative process. “What’s interesting about this way of acting — with no sets, no costumes, just these silly suits with dots all over your face, is that you can do the whole scene and it goes very quickly because you don’t have to break it up the way you do on a conventional film. And Robert Zemeckis is a pretty free and easy director, although he has a strong vision and knows what he wants. We’d play a five or six page scene out in its entirety and after maybe five or six takes, whenever Bob was confident he had the performances, we’d move on. So, my character appears early in the drama, maybe page three or four of the script, and finishes on page 76, but I worked on the film for only about eight days, which is an impossible schedule on a traditional film. The first day I was a little apprehensive but the process gives you a great sense of freedom, that anything goes,” Hopkins says.

Hopkins, the first actor cast, decided to use his native Welsh accent “because Welsh is an ancient language, several thousand years old.” Zemeckis notes that “there were long debates about how Welsh might have grown out of Old English. Whatever it was, when Anthony said these wonderful phrases that Roger and Neil wrote in his Welsh accent they sounded perfect.”

Wright Penn and Zemeckis had worked together before on the Oscar-winning “Forrest Gump.” As in that film, the “Beowulf” story follows her character through several decades. “Robin is so subtle and wonderful and real and grounded in everything she does as an actress. She brought a maturity to the part, even when she was playing Wealthow as a 16-year-old girl. That’s another great thing about working in performance capture. Robin was able to bring all her experience to this part and the technique allowed her to appear as a teenager and to follow her saga as an adult. She was just magnificent. She understood the torment and the pain Beowulf is putting her through and she played it with such realism that it takes your breath away,” says Zemeckis.

Beowulf falls for Wealthow when he comes to save her husband’s kingdom. But like King Hrothgar, Beowulf’s fatal flaws, his lust for power and glory, his weakness for other women and the Faustian bargain he makes with a demonic but beguiling seductress, ultimately poison his relationship with Wealthow.

“She marries King Hrothgar at a very young age, an arranged marriage, and he is unfaithful,” Wright Penn observes. “Wealthow later falls in love with Beowulf when he comes to save them and, sadly, the pattern repeats itself. In way, she falls in love with the hero and becomes blind to what true heroism is. Beowulf is a hero but, ultimately, he is a human being and when he betrays her — just as the king did, she loses the love and admiration she had for him.”

Crispin Glover, another Zemeckis alumnus, plays the tortured monster Grendel. “I worked with Crispin on `Back to the Future’ and, for some reason, I just saw Crispin playing this guy,” Zemeckis says. “He loves to portray creatures and characters who are deformed, both physically and mentally. I just knew that Crispin would understand Grendel. He didn’t play Grendel as just a monster, he created a character who was helpless and tormented but who also happened to be a physical monstrosity, someone who was persecuted and literally demonized because of what he looked like. Crispin brought a tremendous warmth and humanity to this unbelievable, hideous creature. The only note of direction I gave him was that everything Grendel does causes him physical pain. Crispin took that bit of direction and ran with it. He used his entire body — every cell, every strand of hair — as an instrument when he performed.”

“I hadn’t worked with Bob for 21 years since in the first `Back to the Future’ film. So I was kind of surprised,” says Glover. “But I knew of Beowulf and Grendel and I thought it sounded like a great part. I was working on another film, so I couldn’t come in to meet with everyone. They asked me to put myself on tape. I did that at home with my computer and sent it in. Eventually I was able to read for Bob and he liked what I did and I got the part. I’m very glad I did because it is a great role.”

Grendel’s sole confidante, guardian and avenger is, of course, his mother — a dangerous, seductive creature who plays on men’s flaws and weaknesses to her own devilish advantage. Angelina Jolie was chosen for the role of this magnificent fiend. “Grendel’s mother is a demon and a seductress to the nth degree and nobody can do that kind of sultry character as well as Angelina Jolie,” says Zemeckis.

“When she stepped on the set and became that character, it was a powerful thing to watch. She was just magnetic and she hypnotized everyone on the set.”

For Jolie, performance capture was alluring and powerful. “I loved it. At first, I thought, oh this is going to be so weird, all of us actors with these dots on our faces, in these wetsuit-type costumes, with no props or sets… but what it really does is strip everything down to the essentials of performing, especially in the scenes between Crispin and me — they were just pure amazing emotion. There is so much freedom to just be everything, in the moment, give it your all, because it’s being covered completely and you can overlap and you can play and you can improvise. There’s also an immediate friendship between the actors. When you’re both covered in dots, you become very close and you rely on each other. What’s also great about the process was that it felt like every single crew member was integral to it and equally in the moment with the actors. It’s not like we were hanging out in our trailers and would come in and do a scene from time to time, everyone was in it, every second,” she notes.

A bemused Jolie notes that “when you mention Grendel’s mother, you find that everyone has an opinion about her. I think she’s lovely and everybody else thinks she’s a bit off.”

The character’s actions, Jolie points out, are beyond good and evil, driven by a profound maternal instinct. “Yes, she’s a monster, but she’s also a mom and that’s the essence behind everything she does. Grendel is like a full-grown man but there’s something vulnerable and childlike about him. I thought about her as a mother. If someone hurts your son, you would go to the ends of the earth to avenge him. So, I approached it that way.”

Although Jolie had seen sketches of what her character would ultimately look like — she describes her as a “sexy lizard” who could assume a quasi-human form — personifying the beguiling woman-reptile, without benefit of costumes, prosthetics, props or make-up was a unique experience. Jolie had to piece together her role based partly on Zemeckis’ direction.

She ended up as a fantastically alluring, wily, dangerous female creature of iridescent gold with high-heeled cloven feet and an appendage-like braid of hair.

Zemeckis elaborates: “We had this idea that she would have a long braid of hair that is sort of like a tail. So we could get the right feel and movement of her tail/braid, I actually had her do a take where she moved her hand in the same way her tail would, to get the right feel. And the rhythm was perfect. That’s what I love about this art form — you get the actors’ interpretation of everything, including what a magical tail might move like,” he says.

The performance capture process also allows the actors to lend their talents to several characters and their performances inform everything about the ultimate animated representation of their characters. Director Zemeckis used John Malkovich’s gifts this way to great effect, as Unferth, who is initially skeptical of Beowulf’s legend and intentions and, later, when he plays his own son.

“John is one of my favorite actors. He can do anything and you never know what you’re going to get with him,” says Zemeckis. “He put such a spin on Unferth and completely understood what we wanted from the nemesis of Beowulf, the naysayer who debunks our hero and accuses him of exaggeration. When John got his hands on that and the accent — I can’t even describe it, but it was just the most magnificent interpretation of the character. And the great thing about performance capture is that it allowed John to not only play his son but himself as an older man. He played it as if he had had a stroke and survived it with a physical debilitation. So, based on his performance, we could make him look drawn and withered away.”

Malkovich remembers reading Beowulf as a teenager. “I had not looked at it since we were forced to read it in our high school literature class. My school was old-fashioned, we actually still had to read it. So I did know of it,” he says. He adds that in general “I think it is always dangerous to compare a movie script with the source material, whether it be a novel or a piece of non-fiction, or, in this case, an epic poem.” For Malkovich, the script’s ominous elements were appealing. “I thought it was a very good script, quite dark and exciting, in the fashion of mythic fairy tales,” Malkovich says.

Rounding out the cast is veteran British actor Brendan Gleeson, as Beowulf’s trusted companion and steadfast warrior Wiglaf. Wiglaf fights to the end with his king. Although he harbors suspicions about Beowulf’s secrets and his true intentions, ultimately Wiglaf inherits Beowulf’s legacy of glory and temptation. What he does with that is left to the audience to decide.

At first, Gleeson had some misgivings about joining the cast of “Beowulf” — qualms Zemeckis soon allayed. “I have to admit I had a certain resistance to the movie because I had done a number of epic films — I had been in “Troy” and “Kingdom of Heaven” — and I was a little bit afraid of becoming `That Guy.’ It was only when I met Bob tha t I changed my mind. His enthusiasm was phenomenal and the process was fascinating,” Gleeson says.

A Short History of Beowulf

The events of Beowulf, which is a single poem 3,000 lines long, takes place in the 6th century A.D. — based on the mention of a battle for which there is corroborating evidence. Though most of the story transpires in Denmark, it was told by Anglo-Saxons in northern England two hundred years after the fact. The Anglo-Saxons did not see themselves as British, but as Vikings and all their heroes were from Scandinavia.

The actual author of Beowulf is unknown. The original poem was written down on thin sheets of shaved leather. It was later copied and re-copied over the next two hundred years. By the 900s, it had been collected in a volume that also contained the story of San Christopher, a collection of outlandish anecdotes about the Far East, an alleged letter from Alexander the Great and a poem about the Biblical heroine Judith.

This volume was partially destroyed in a fire at The Cotton Library, the world’s greatest collection of literature from the Middle Ages, on October 23, 1731. Not only was the document charred, but the poem’s reputation suffered over the ensuing years. Written in Old English, it was deemed confusing in its mixture of pagan and Christian themes. Structurally, it was seen as flawed because it had three antagonists instead of one, the last of whom was separated from the other two by half a century.

In addition, Beowulf doesn’t rhyme; it alliterates instead. It has no iambic pentameter because, according to the Anglo-Saxon storytellers, it didn’t matter how many syllables a line had as long as it was short and had three alliterations in it. By comparison to ancient masterpieces like Homer’s Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid, Beowulf just seemed like bad poetry. Worse, its heroism and morality was centered on a man fighting monsters. Scholars couldn’t really take a poem about trolls and dragons all that seriously.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that Beowulf was reassessed by none other than J.R.R. Tolkien, the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. In his 1936 essay “Beowulf: The Monster and the Critics,” Tolkien wrote that the problem everyone was having with Beowulf had nothing to do with its quality, but rather the fact that it was being unfairly compared to Homer and Virgil. Beowulf didn’t conform to the rules of epic poetry created by the ancient Greeks and Romans because it was a Scandinavian tale with its own specific meter — not better, not worse, just different.

And contrary to most scholars before him, Tolkien claimed that the 50-year gap between the fight with Grendel’s mother and the battle with the dragon was exactly what gave the poem its claim on greatness. Beowulf, he wrote, was not the story of a young hero who triumphs over monsters, nor is it about an old king who dies trying to kill a dragon, but instead it is the combined tale of a man who, once young and impervious, knowingly proceeds to his own tragic death. It was precisely the two halves of the story that made it work.

Without Tolkien’s reassessment, Beowulf would have remained an obscure text read only by doctoral candidates in medieval English literature. Today it is widely read in high schools across the country. Tolkien not only revived the poem’s reputation, he imitated it in his own works. The Two Towers chapter, “The King of the Golden Hall,” is lifted from the beginning of Beowulf. The fire-breathing dragon in Beowulf, who rises in anger after a thief steals his treasure, is mimicked in the climax of The Hobbit.

Other writers have used the poem in their own literature. Author John Gardner wrote the popular 1971 novel Grendel, a philosophical musing by the monster about the randomness of life. Michael Crichton, of Jurassic Park fame, took all the monsters out of the story and wove a historical action fantasy called Eaters of the Dead.

— “Excerpted from the essay by Jason Tondro, Ph.D., Issue #3 of the BEOWULF Comic book series from IDW Publishing.”

Production notes provided by Paramount Pictures.

Beowulf

Starring: Angelina Jolie, Anthony Hopkins, Ray Winstone, John Malkovich, Brendan Gleeson, Dominic Keating, Alison Lohman, Robin Wright Penn

Directed by: Robert Zemeckis

Screenplay by: Roger Avary

Releas: November 17, 2007

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for intense sequences of violence including disturbing images, some sexual material and nudity.

Studio: Paramount Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $82,195,215 (41.9%)

Foreign: $114,068,876 (58.1%)

Total: $196,264,091 (Worldwide)