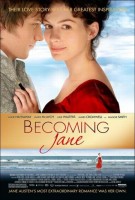

Tagline: Their love story was her greatest inspiration.

Becoming Jane is an imaginative romantic comedy in the spirit of Jane Austen that places young Jane herself at the center of a witty, enchanting romance not unlike those that would later captivate millions in her celebrated works of literature.

The film spins the few known facts surrounding Austen’s real-life flirtation with the Irish lawyer, Tom Lefroy, into a tale about the kind of personal passion and social complications that could have inspired Jane to become the ingenious and utterly timeless observer of human relationships and romance that she soon did. Indeed, the story playfully references the characters and themes that wend their way through her six novels.

The year is 1795 and young Jane Austen (Anne Hathaway) is a feisty 20 year-old and emerging writer who already sees a world beyond class and commerce, beyond pride and prejudice, and dreams of doing what was then nearly unthinkable – marrying for love marrying for love, without any regard for financial well-being at all; in other words, their romance was based not on sense, but on sensibility or feeling, as the word meant in her day and in her book title, Sense and Sensibility.

Naturally, her parents (Julie Walters and James Cromwell) are searching for a wealthy, wellappointed husband to assure their daughter’s future social standing. They are eyeing Mr. Wisley (Laurence Fox), nephew to the very formidable, not to mention very rich, local aristocrat Lady Gresham (Maggie Smith), as a prospective match. But when Jane meets the roguish and decidely non-aristocratic Tom Lefroy (James McAvoy), sparks soon fly along with the sharp repartee. His intellect and arrogance raise her ire – then knock her head over heels.

Now, the couple, whose flirtation flies in the face of the common sense of the age, are faced with a terrible dilemma. If they attempt to marry, they will risk everything that matters – family, friends and fortune. But navigating the stormy waters between romance and duty, heart and head, sensibility and sense, goodness and greatness is all a part of BECOMING JANE.

The Origins of the Story

It has long been surmised that Jane Austen, who wrote so brilliantly of romantic relationships yet herself remained unmarried, never knew undying passion. Yet recently, this notion has been turned upside down by several Austen historians who have proposed the possibility of a fervid romance between 20 year-old Jane, fresh off beginning her adult writing career, and the equally young, ambitious and smart Irishman Tom Lefroy. Was it this seemingly brief, deep love affair – with its apparent rapid build-up and heartrending demise — that inspired the great romantic novels Austen was about to write?

The full truth of what really happened between Austen and Lefroy will never be known. The importance and extent of Austen’s true feelings for Lefroy will continue to be hotly debated. And yet, the thrilling notion of Jane Austen in the middle of her own heated, rebellious love story was nearly irresistible to fertile imaginations who saw it as an intriguing jumping off point for a fictional, fun romantic comedy in the Austen spirit.

Thus was born BECOMING JANE, a film that boldy imagines what might have happened if a youthful Jane Austen fell in love. The story not only places Jane at the center of her own courtship story, but merrily and artfully filters characters and elements from each of Austen’s six novels into the mix.

Bringing a modern sensibility to the story is director Julian Jarrold, who made a rousing feature film debut with the critically admired comedy Kinky Boots. The film pairs rising young stars Anne Hathaway, most recently seen starring in the hit comedy The Devil Wears Prada, and James McAvoy, who came to the fore in the Oscar-winning The Last King of Scotland, as Jane Austen and the man who, perhaps, might have stolen her heart and awakened her still deliciously relevant views on how status, money, family, freedom and true love really work.

There have, of course, been scores of movies drawn from or inspired by Austen’s famous books – Emma, Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, Persuasion, Northanger Abbey and Mansfield Park – ranging from boldly contemporary comedies to painstaking period adaptations. Indeed, People Magazine recently declared that we are living “in a Jane Austen moment.” As Joan Ray – an Austen scholar, former President of the Jane Austen Society of North America and Professor of English at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs – notes: “The amazing thing about Jane Austen is that she appeals to pop culture, to academic scholars, and to everyone in between. She’s so multi-layered and so in tune with human nature, she can be approached on so many different levels.

Yet, suprisingly, Austen herself has never been a cinematic character, until now. It all began when screenwriter Sarah Williams first learned about the possible serious romance between Austen and Lefroy – and couldn’t help but try to envision what might have really gone on between them, behind doors that will always be closed to us more than 200 years later.

Williams was aware that there was only a handful of known facts about Austen and Lefroy, which had produced multiple interpretations, ranging from biographer Jon Spence’s belief in their sharing a deep and abiding love to others who saw nothing but the couple’s enjoying a frivolous flirtation between them. But this open-ended reality would allow Williams, and later co-writer Kevin Hood, the freedom to turn the speculative story of Austen’ youthful flirtations into the kind of delightful and dramatically satifsying romantic fiction Austen herself continues to inspire.

Wiliams approached Douglas Rae and Robert Bernstein of Ecosse Films, which had previously won acclaim for the film Mrs. Brown, starring Judi Dench in another unlikely love story between historical figures – that of Queen Victoria, the most powerful woman in the world, and the lowly Scottish highlander in whom she confided. Though BECOMING JANE would delve deeper into fiction, the premise grabbed the producers. “It was intriguing to think that beneath Jane Austen’s strict interior was a beating heart which could have been awoken by this relationship,” says Bernstein.

Rae and Bernstein subsequently recruited accomplished writer Kevin Hood to bring fresh insight to the script. “Kevin has a wonderful romantic sensibility,” says Bernstein. “There is a poetic quality about his writing as well as a rigorous emotional truth which we all thought was important for BECOMING JANE.”

Hood was instantly compelled by the story and the argument of some historians that Tom Lefroy stirred Jane Austen’s heart far more than anyone ever realized. Although it would require time travel and telepathy to know in truth what had occurred between the two, Hood was more inspired by the idea that this rumored brush with doomed passion could become a window into the themes of which Austen is still considered the ultimate master. “The period of a woman’s life before marriage was what she always wrote about. It was a subject of perpetual interest to her. She also returned again and again to the figure of the attractive, unreliable young man,” Hood notes. “So arguably, this could be based on her personal experience. That was our starting point.”

From there, Hood began weaving fact and fiction together, merging elements of Austen’s real life with witty allusions to events and characters from her novels, turning the screenplay into a fun, fresh take on the universe Austen created. “The majority of characters seen in the film did exist, as did many of the situations and circumstances,” he explains. “Throughout, we weave together what is now known about Austen’s world from her books and letters, creating a rich Janeite landscape.”

When producer Graham Broadbent of Blueprint Pictures read the completed script, he was immediately impressed by its boldly different perspective. “This is Jane Austen not as a dusty old spinster [as promoted by the Victorians] but as a 20 year-old in a love affair which couldn’t proceed further for societal reasons and other pressures of the time. What the writers had done was to take the encounter between Jane and Tom Lefroy, mesh it with Jane’s real family and other known experiences and set it all against a wonderfully imaginative world inspired by Austen’s fiction.

The result was something that, like Austen herself, seemed both new and timeless. Sums up Bernstein: “At bottom, BECOMING JANE is simply a love story about two young people who know they can’t be together. There’s humor in their interaction, which in the beginning has a sort of screwball element, but the characterizations are also very sophisticated. Ultimately, it’s very accessible because Jane and Tom are dealing with issues people still deal with all the time.”

Now, the producers set out in search of a director who could bring his own distinctive, modern touch to the story. They quickly found themselves drawn to Julian Jarrold, who had brought both heart and humor to his debut feature, Kinky Boots, an uplifting comedy about a female impersonator who turns the fate of luckless shoe factory around. “I liked Julian’s style because it was modern and visceral, and I just had a feeling that he was the right choice,” says Bernstein. “This piece needed to be handled with delicacy but also with a certain amount of brio, and Julian had both.”

Jarrold, already a fan of Austen, was knocked out by the screenplay and inspired by its potential. “It is a love story but much more besides, with so many layers and interesting ideas,” says the director. “Apart from the romance, I was very attracted by the themes of imagination and experience. I thought the writing was fresh and surprising and offered a fascinating insight into Austen’s life, focusing on her as a young woman full of exuberance. I was also very attracted to the more provocative scenes that don’t normally appear in an Austen film. We see the more risqué side of Regency life, a side that Jane Austen was certainly aware of, but only occurs off-stage in her novels.”

The excitement also came with an acknowledged risk, however. In approaching Jane Austen’s youth and heart in such an imaginative way, Jarrold knew he would be stepping into dangerous territory. He was well aware of how lovingly devoted some Austen’s fans are and how staunchly loyal some can be to upholding her Victorian legacy. But even so, Jarrold couldn’t resist the idea of allowing the vaunted icon to become a real woman with complex emotions and a vulnerable heart for the first time on screen.

“Everyone has their own treasured image of Jane Austen,” says Jarrold. “Yet, despite the huge numbers of biographies, we know so little about her real life. Her letters are an important source of information, but unfortunately, many have not survived. Her first letter about her ‘flirtation’ with Tom Lefroy probably survived only by mistake. With this film I wanted to see Jane portrayed as a real person of flesh and blood and not as a museum piece.“

Jarrold couldn’t wait to reveal Austen not as the prim and proper spinstress of of the old, Victorian stereotype, to which some fans still cling, but as a young woman and artist very much in love with life and its infinite possibilities. “I hope BECOMING JANE works as a fresh and interesting take on the world of Jane Austen,” he summarizes. “I hope the poignancy between the happiness she allows her heroines and the reality of her life resonates with people. I hope it brings even more people to her books and reveals another side to the author we still love so much.”

Jane and Tom: What We Know… And Don’t Know

Jane Austen and Thomas Langlois Lefroy met during the Christmas holidays of 1795 at a ball thrown by Tom’s Aunt and Uncle in Hampshire. At the time, Austen was just starting to write what her father would dub “tales in a style entirely new” and had recently finished, at age 18 or 19, the novel, Elinor and Marianne, which Austen would rework after 1809 as Sense and Sensibility. For his part,Tom Lefroy was also just 20 years old, and a quick-witted young Irishman on his way back to London to study law.

Austen wrote of their frolicsome flirtation to her only sister Cassandra – and it is these few tantalizing words that have inspired multiple interpretations. In her first mention of Lefroy, Jane describes him as “a very gentleman-like, good-looking, pleasant young man” (Letter of Jan. 9-10, 1796, her first existing letter).

A short time later she writes: “I rather expect to receive an offer from my friend in the course of the evening. I shall refuse him, however” ” (Letter of Jan. 14-15). She also tells Cassandra that she danced three times with Tom, breaking the so-called “two dance rule” that defined a casual encounter, and setting off gossip and rumors.

Sometime after January 15th, however, Lefroy leaves to return to Lincoln’s Inn (law school), London, in time to settle in for the new term, beginning January 23rd. After her January 1796 letters, Jane only mentions Tom in one additional surviving letter, dated November 17-18, 1798, written to Cassandra.

Tom’s aunt, “Madam” Lefroy, as she was called, stopped by the Austens’ parsonage and fails to speak of Tom to Jane, who touchingly writes that she was “too proud to make any enquiries; but on my father’s afterwards asking where he was, l learnt he was gone back to London in his way to Ireland.” He became engaged in October, 1797, and married in 1799 the wealthy, Irish Mary Paul, with whom he eventually had seven chldren. Austen would remain a single woman, and in 1809, she, her sister, and mother returned to their native Hampshire, moving into a pleasant cottage in the tiny village of Chawton.

Here Jane performed her minimal household duties, while revising her earlier manuscripts of Elinor and Marianne into Sense and Sensibility and First Impressions into Pride and Prejudice and composing Mansfield Park, Emma, and Persuasion, which, along with Northanger Abbey (1803) are regarded as among the world’s greatest novels. Fewer than fifty years after her death, Austen would be widely compared to Shakespeare in the quality and universal appeal of her work.

Other than what appears in Austen’s letters, that is all that is certain about the pair. From these facts, however, has come a great deal of analysis, interpretation and even playful conjecture. After all, historians have long wondered how Austen was able to write so vividly of the bliss of love, the gravity of loss and the compromises involved in affairs of the heart. Did it all spring from her clearly vast and insightful imagination and her wide and retentive reading – or was there also a heart-rending personal experience behind it?

Jon Spence and Claire Tomalin are two of several leading historians who have come down on the side of personal experience. It was Spence’s 2003 biography, Becoming Jane Austen, that put forth the most extensive argument yet that Austen had far more than just a fun flirtation with Tom Lefroy. Rather, he surmises that Jane developed a deep romantic love for Lefroy that would become of great significance in her life and especially her writing. Based on his study of Austen’s letters, novels and other circumstantial evidence, Spence believes that Austen and Lefroy saw each other again well after Christmas 1795 – at a fateful meeting in London where Jane was unsuccessfully vetted, and ultimately rejected, as a dowry-less marriage possiblity for Lefroy.

Spence also believes that, while Tom moved on in typical male fashion, Jane remained very much in the throes of heartbreak, emotions that helped to fuel some of her most accomplished writing. He notes that shortly after this alleged meeting, Jane began writing at a furious pace, beginning Pride and Prejudice almost immediately. “She was creatively on fire,” writes Spence.

Yet, when Lefroy returned to Hampshire two years later and did not visit Jane, she suddenly descended into a 10-year break from writing novels. Of course, part of this period (1800-05) encompasses Mr. Austen’s retiring and moving his wife and two daughters to Bath, where they lived in rented property; Mr. Austen died quite suddenly in January 1805, leaving the three Austen ladies to live something of a nomadic life of genteel poverty, relying on the kindness of family members, until Edward Austen, another of Jane’s beother, offered his sisters and mothers the cottage in Chawton.”.

Award-winning historian Claire Tomalin’s 1997 biography Jane Austen: A Life also went in search of fresh insight into what motivated Austen’s surge of creativity. In the book, she analyzes Jane’s letter of January 9, 1796, written to her sister Cassandra about her encounter with Tom Lefroy at the ball, concluding that it is the “only surviving letter in which Jane is clearly writing as the heroine of of her own youthful story, living for herself the short period of power, excitement and adventure that might come to a young woman when choosing a husband; just for a brief time she is enacting instead of imagining.”

Tomalin finds in the letter the tenor and tone of a woman in love and, like Spence, believes that the outcome of her dalliance with Lefroy resonated deeply in her artistic life. She summarizes of Jane and Tom: “A small experience, perhaps, but a painful one for Jane Austen, this brush with young Tom Lefroy. What she distilled from it was something else again. From now on she carried in her own flesh and blood, not just gleaned from books and plays, the knowledge of sexual vulnerability; of what it is to be entranced by the dangerous stranger; to hope and to feel the blood warm; to wince, withdraw, to long for what you are not going to have and had better not mention. Her writing became informed by this knowledge, running like a dark undercurrent beneath the comedy.”

The theoretical musings of Tomalin and Spence, however, will likely always remain conjecture. Jane herself never wrote any further of her feelings, so they have been forever rendered an open mystery. As for Tom Lefroy, in his old age he was asked by a nephew if he had actually once been in love with Jane Austen. Lefroy answered that he had, adding wistfully however, that it had been “a boy’s love.”

In 1802, Austen received a confirmed proposal, this time from the shy but very well-off brother of Austen’s dear friends, Catherine and Alethea Bigg, Harris Bigg-Wither. Austen initially accepted but a day later, turned Bigg-Wither down, remaining a “spinster,” albeit one with a tremendous understanding of romance and an active social life among friend and family, until her death at the age of 41, probably of Addison’s disease, which was undiagnosed until 1855, thirty-eight years after her death (1817).

Observing Jane: How Jane Austen’s Fiction Informs Her Character in Becoming Jane

In a kind of reverse engineering, BECOMING JANE utilizes key scenes and characters from Jane Austen’s novels — from the beloved Pride and Prejudice all the way to the lesser known Northanger Abbey and Persuasion — to forge the film’s depiction of Jane and Tom as a man and woman caught up in a courtship driven by heady feelings but complicated by money and mores. Austen scholar Joan Ray has identified several areas after a single viewing where the film converges with Austen’s fiction, including:

• Harking back to Pride and Prejudice, Jane’s character resembles both the flirtatious Lydia Bennet who loved to dance and later Elizabeth Bennet who engages in witty repartee with Mr. Darcy, much as Jane does with Tom Lefroy in BECOMING JANE.

• Tom Lefroy at first resembles Wickham, who in Pride and Prejudice was studying law with rather haphazard study habits, and also Darcy in the pejorative way he tends to judge country people.

• Lady Gresham, the character played by Maggie Smith, closely resembles Catherine de Bourgh from Pride and Prejudice – Darcy’s wealthy aunt who didn’t want Elizabath Bennet to marry Darcy. Lady Gresham is controlling and opinionated, like Lady Catherine, and Jane in the film even runs aside to scribble a note when Lady Gresham mentions a “little wilderness or shrubbery,” just as Lady Catherine does when she visits Elizabeth to discourage her from marrying Darcy.

• The clumsy Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejduce is echoed in BECOMING JANE’s klutzy young clergyman Mr. Warren. Warren also resembles Mr. Elton in Emma with his unexpected proposal.

• Jane’s heightened emotional reactions resemble those of the sensivite Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensiblity.

• In BECOMING JANE, Countess Eliza has a pug dog, just as she did in real life, and as does Lady Bertram who spends her days on the couch petting her pug in Mansfield Park.

• In Mansfield Park, Lady Bertram tells her impoverished niece Fanny Price that it is every woman’s duty to marry well and Lady Gresham is given similar lines in BECOMING JANE.

• Jane Austen is shown playing cricket in BECOMING JANE, a favorite pastime of young Catherine Morland, the heroine of Northanger Abbey.

• Jane and Tom visit the popular Gothic novelist Ann Radcliffe in BECOMING JANE, while Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey is reading Radclliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho, which fires her imagination.

• In Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen defends the art of writing novels, noting that it is in books that “the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humor are conveyed to the world.” Jane is given a similar line as a young writer in BECOMING JANE.

• The scene where Jane and Tom are in the staircase in Uncle Benjamin’s house provides a quick homage to the staircase scene with Henry Tilney and Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey.

• The heroine of Persuasion, Anne Elliot, breaks off her engagement with Frederick Wentworth, despite her true love for him, in a similar fashion to the way Jane does with Tom Lefroy in BECOMING JANE.

• When BECOMING JANE imagines Jane meeting Tom Lefroy again at a concert of Italian music this mirrors the moment in Persuasion when Anne Elliot sees Wentworth at a concert and, though realizing that he loves her, is unable to communicate with him, wondering “How was the truth to reach him?”

Anne Hathaway Becomes Jane

Jane Austen is widely regarded as the greatest English writer since William Shakespeare, with novels that continue to enrapture and inspire readers around the world, even propelling the current craze for “chick lit.” Yet, in the popular imagination, Jane herself is most often depicted as so prim and proper that one could barely get to know her. In BECOMING JANE, audiences will see a different, more intimate portrait of Austen – as a cautiously ambitious, whimsically humorous young woman, already wholeheartedly devoted to her love of words, but also starting her adult life with the same feisty independence that was to become a trademark of her most popular fictional heroines. On the cusp of womanhood and of true greatness, she refuses to be fettered by social imperatives or restricted by her gender – much to her parent’s chagrin.

“Our Jane is full of life and youthful exuberance. She is also tough, intelligent, unsentimental, precocious, witty, and a little above her station in rural, sheltered Hampshire,” says Julian Jarrold. “She is independent-minded and looking for an intellectual equal. So when the charismatic, roguish but intelligent Tom Lefroy arrives, the sparks begin to fly.”

The filmmakers knew the role would be no easy bill to fill – and were especially surprised when the clear winner came down to a rather unconventional seeming choice, the American actress Anne Hathaway. The New Yorker had already proven herself as an actress of contrasting refinement and Audrey Hepburn-like charm, winning international acclaim as the ingénue royalty in the box office hit The Princess Diaries, playing a hardnosed businesswoman in the Academy Award-winning Brokeback Mountain and doing a comic turn in the high fashion satire The Devil Wears Prada. But it was Hathaway’s profound love of Austen, knowledge of her works and total dedication to portraying the writer that took Jarrold and the producers by storm, winning them over.

“When I met Annie, I knew she was the right person for the job,” recalls Jarrold. “She was so passionate about Jane Austen and already an expert on her novels. She’s very bright, hardworking and committed. She was completely dedicated to doing the research, developing an immaculate English accent, learning piano, mastering the dances and the manners of the period. She even learned a rudimentary sign language taught to her by Philip Culhane who is partially deaf and plays her brother George. I also believe Annie has a fresh, lively and provocative attitude, which is just right for the part of a young woman who rails against the pressures of the marriage market. And there was fantastic chemistry between her and James McAvoy.”

Robert Bernstein adds: “We saw something special in Brokeback Mountain and the fact that Anne is also such a great admirer of Jane Austen really meant something. Anne gives the character of Jane a vulnerability which is very captivating.”

Hathaway had been avidly reading Austen since the age of 14. “In high school, I did a comparative paper on Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility,” she says. “I fell in love then with Jane Austen and the world she created.”

Reading the screenplay for BECOMING JANE reawakened Hathaway’s love for that world – and expanded upon it in a fun and imaginative way by putting Jane herself the center of a breath-taking but impossible romance. “I was so impressed with how intelligently written the script was and how emotional and passionate it was,” she says. “What I also loved about it was that it captured a young couple falling deeply in love with each other. That appealed to me and also the fact that it didn’t have a fairytale ending. It is such a classically written drama and it has a timeless quality.”

When Hathaway told her mother about the role, she provoked an interesing reaction. “She said, ‘That seems right,’” recalls Hathaway. “I asked what she meant and she said: ‘You’ve always felt a connection to Jane Austen.’ My mom made me realize how much I wanted the part.”

Once the deal was sealed, Hathaway immersed herself in every known detail of the writer’s life and times. “I re-read Jane Austen’s entire canon and read quite a few biographies,” she notes. “I also read critical essays on her, read her letters and researched the Regency period. I really tried to leave no stone unturned. By the end, Julian was prying the books out of my hands.”

Hathaway not only had technical challenges to face, inclduing a new accent, a complex etiquette to master, she also had to confront the considerable pressure of playing one of the most adored writers in all of literary history. “It was daunting,” she admits. “Playing someone so beloved and of whom people are so fiercely protective was nerve-wracking. But I wanted to do justice to the role, not just as an actress but someone who is true fan of Jane Austen.”

She also understood that this more spirited, fictionalized portrait of Austen might be viewed by some as provocative. “We all sat down early on and agreed that we were going to make a movie that may be contrary to the traditional perception of Jane Austen and her world,” she says. “We made certain assumptions about Jane and gave her certain characteristics. In some of her own letters she wrote about how she was hung over after attending a ball and that’s not something that we necessarily think of when we think about Austen. But I was very excited to present a woman who was flesh and blood and not simply someone who had an icy wit and tea running through her veins. I wanted to show her as a very modern woman, a woman who truly had a sense of her own worth and seemed to know the value of love, even in those times.”

Hathaway loved Jane’s initial quick-witted encounters with Tom Lefroy, as they flirt, argue, banter and dance around one another, taken aback and surprised by the sheer strength of their feelings. “They initially rub up against each other the wrong way,” says the actress. “In a way though it is kind of like two magnets pushing against each other. All you have to do is flip them and they are pulled together. Of course, Jane didn’t have a lot of people she could talk to who could match her. So, when suddenly Tom Lefroy comes into her life and he is matching her quip for quip, it is something new for her. In a world obsessed with propriety, they realize that when they are together, they can actually be themselves.”

Of course, Jane and Tom are quickly aware of the potential consequences of their affection – and that their growing love will be pitted against economic status and the plans their parents have for their respective marriages. Hathaway sees Jane in the film as struggling with how to be a good daughter while giving the creative greatness within her the freedom to blossom.

“I think it was difficult to be a daughter in Austen’s time,” says Hathaway. “There was a lot expected of Jane that she railed against. Her relationship with her mother, while obviously rooted in love, was volatile. But her mother came from a caring place. She wanted to see her daughter settled and in her mind that was what was best. Jane saw it otherwise and it often came to emotional blows.”

Despite the difficulties of the age for women, Hathaway came to adore some of the more romantic aspects of Regency England, with its less frantic pace and greater room for reflection. “I’m not really a good twenty-first century girl. I don’t like texting, I hate email and I break computers. There was such wonderful grace in Jane’s time, so it was really fun for me to live in that period for a few months,” she says, adding: “I could do without the corsets, however.”

Production notes provided by Miramax Films.

Becoming Jane

Starring: Anne Hathaway, James McAvoy, Maggie Smith, Julie Walters, James Cromwell, Helen McCrory

Directed by: Julian Jarrold

Screenplay by: Kevin Hood, Sarah Williams

Release Date: August 3rd, 2007

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for brief nudity and mild language.

Studio: Miramax Films

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $18,670,946 (50.0%)

Foreign: $18,640,726 (50.0%)

Total: $37,311,672 (Worldwide)