August Rush tells the story of a charismatic young Irish guitarist (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) and a sheltered young cellist (Keri Russell) who have a chance encounter one magical night above New York’s Washington Square, but are soon torn apart, leaving in their wake an infant, August Rush, orphaned by circumstance. Now performing on the streets of New York and cared for by a mysterious stranger (Robin Williams), August (Freddie Highmore) uses his remarkable musical talent to seek the parents from whom he was separated at birth.

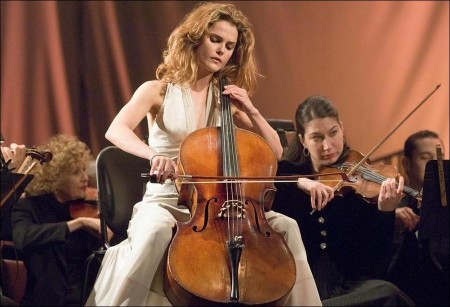

Twelve years ago, on a moonlit rooftop above Washington Square, Lyla Novacek (Keri Russell), a sheltered young cellist, and Louis Connelly (Jonathan Rhys Meyers), a charismatic Irish singer-songwriter, were drawn together by a street musician’s rendition of “Moondance” and fell instantly in love. Sharing the language of music, their connection was real and undeniable…but short-lived.

After the most romantic night of her life, Lyla promised to meet Louis again but, despite her protests, her father (William Sadler) rushed her to her next concert—leaving Louis to believe that she didn’t care. Disheartened, he found it impossible to continue playing and eventually abandoned his music while Lyla, her own hopes for love lost, was led to believe months later that she had also lost their unborn child in a car accident. Years passed with neither of them knowing the truth.

Now, the infant secretly given away by Lyla’s father has grown into a spirited and unusually gifted child (Freddie Highmore) who hears music all around him in the rhythms of life and can turn the rustling of wind through a wheat field into a beautiful symphony with himself at its center, the composer and conductor. Orphaned by circumstance, he holds a profound and unwavering belief that his parents are alive and want him as much as he wants them—if only they could find each other.

Determined to search for them, he makes his way to New York City. There, lost and alone, he is beckoned by the guitar music of a street kid playing for change and follows him back to a makeshift shelter in the abandoned Fillmore East Theater, where dozens of children like him live under the protection of the enigmatic Wizard (Robin Williams). That night, he picks up a guitar for the first time and unleashes an impromptu performance in his own unique style.

Astonished that this untrained boy can play so passionately, Wizard names him August Rush, introduces him to the soul-stirring power of music and begins to draw out his extraordinary talent. Wizard has big plans for the young prodigy but, for August, his music has a more important purpose. Never giving up hope of finding the parents he knows are out there somewhere, he calls out to them through every note. He believes that if they can hear his music, they will find him.

Unbeknownst to August, they have already begun that journey. Having just learned her son is alive, Lyla is already working desperately to locate him with the help of dedicated social worker Richard Jeffries (Terrence Howard) while Louis, still haunted by memories of his one true love, finds himself returning to his musical roots and retracing his steps to the place where they met. Separated by the events of life but bonded by love and music, Lyla, Louis and August search for what they lost and what will make their lives complete again…each other.

About the Production

“I believe in music the way some people believe in fairy tales. What I hear came from my mother and father. Maybe that’s how they found each other. Maybe that’s how they’ll find me…” – August Rush

“This is a story about a child who hears the world differently,” offers award-winning producer Richard Barton Lewis, who nurtured “August Rush” from its inception through every aspect of development and production. “He doesn’t fit in where life initially places him. His one desire is to be with his parents, and no matter how much people try to convince him that they aren’t alive or, worse, that they don’t care, he never gives up believing. No one can talk him out of it. He waits for them for 11 years and then decides it’s time to go look for them himself.” What he doesn’t know is that his parents are just as lost as he is.

Director Kirsten Sheridan explains. “August’s ability to channel music from nature has its origin with his mother, Lyla, a concert cellist, and his father, Louis, a singer, songwriter and guitarist—both of them talented musicians but, more importantly, both similarly attuned to the music that’s all around us but few of us hear. It’s what brought them together. These are two people who have always heard the world in a special, specific way and that has left them a bit on the periphery with other people. When they realize that they each feel the same way, it’s an absolutely magical and immediate connection that breaks them out of their loneliness for that one night and that’s when August is created.

“‘August Rush’ is a love story with three people,” Sheridan affirms.

“But, like so many love stories, things don’t run smoothly. Lyla and Louis are quickly torn apart and remain apart for years. Sadly, upon losing each other, they also lose their passion for music,” adds Lewis.

That the lovers’ separation also results in their unintentional separation from their child— a child they don’t know even exists—gives the story a triangular structure as each must now follow his or her unique journey to the same destination if they are ever to be a family.

“I liked the story’s ensemble nature,” notes Jonathan Rhys Meyers, who stars as the impulsive, creative Louis. “They’re all parts of the same puzzle, these three people separated by circumstance, who need each other to feel fully alive.”

Keri Russell, who stars as Louis’ precious Lyla, says, “I love stories in which people are trying to find where they belong, to find their true home and the people they’re meant to be with. It’s easy to make a poor choice and spend a decade living the wrong kind of life and not as easy to correct that kind of error, but it’s possible. I believe what this story is saying—not just with August but with each of the characters—is that it’s only when you open yourself up to emotion and loss and become vulnerable that you find your way.”

Sheridan concurs. “I’m constantly reminded of how the most profound ideas are often the most basic. What I fell in love with was the central story of this family finding each other through their shared passion for music and how it juxtaposes life’s two extremes: love and loss.”

Freddie Highmore, whose 14th birthday coincided with the first week of filming, describes how this musical influence is a theme established at the very beginning and helps to enhance and propel the story. “Even in the orphanage, August feels connected to the parents he’s never met because he believes they hear the same music he hears in everything around him. Later, when he learns guitar, he can start expressing some of that music and believes he is playing to his parents. One thing leads to another with him just getting better at playing all the time and gaining a wider audience, but it all means the same to him: he’s calling out to these two people. He is absolutely convinced that this is the way to reach them.”

Music as communication is a concept August knows instinctively but it’s the mysterious man known as Wizard who first articulates it for him. Played by Robin Williams, who refers to the character as “a kind of rock-and-roll Fagan,” Wizard serves as August’s first mentor. “You know what music is?” he asks the boy. “A harmonic connection between all living beings.”

With much of the story told through the changing rhythms and moods of music, Lewis greatly credits director Sheridan’s ability to “match sound with camera flow, to sweep, visually, as the music sweeps, always flying to capture August’s soaring point of view. Kirsten brought a facile touch as well as passion, imagination and tremendous heart. It was the purest collaboration I have ever had with a director. She is an amazing storyteller.”

“August Rush” evokes a certain fairytale quality but is grounded in reality—a balance the filmmakers sought to maintain because, as Sheridan attests, “If everything is magical you won’t be able to see the one part of it that is truly meant to be transcendent; it would be like putting a color on top of another color. We wanted the contrast of the real world.”

Citing the truth-is-greater-than-fiction principle, screenwriter James V. Hart notes that even the seemingly fantastic elements of August’s musical prowess could be drawn from reality. “One amazing aspect of this story is that while we were prepping the script for production a child prodigy enrolled at Juilliard—Jay Greenberg, age 12, who had already composed five symphonies. In an interview he stated that he doesn’t know where the music comes from, but that when it arrives in his head it’s completely composed. He sounded like our August.”

“I’ve always been attracted to stories that hint at magic. It’s very seductive because we all want to believe,” says screenwriter Nick Castle, reuniting here with Hart for the first time since their creative collaboration on Steven Spielberg’s “Hook.” “And music is the most mysterious of arts; it seems to bypass the conscious mind and go to some very primal place in us. It’s the perfect medium for the magic in this kind of film.”

As Lewis concludes, “There are no special effects in this movie. The magic is in the performances, the characters and the discoveries they make along the way.”

Casting Process

“It’s like someone’s calling out to me – but only some of us can hear it.” – August Rush

“Only some of us are listening.” – Wizard

Casting on “August Rush” naturally began with the story’s central role. “Finding the right August was essential. If the child does not genuinely touch an audience, this story won’t work. You’re not going to believe him,” states Lewis, who cites Freddie Highmore’s park bench scene with Johnny Depp in “Finding Neverland” as striking exactly the right emotional tone he needed for August. Securing the young actor proved more difficult, as Highmore’s mother had planned for her son to take a break from his film schedule at the time. “But when I described the story to her, she agreed to read the script.”

Taking Highmore’s formidable talent as a given, the producer took an unconventional approach to his interview by putting Highmore together with his own young son and observing their rapport. “Freddie has a unique, genuine, unaffected quality that is entirely his own, as an actor and as a person. You simply fall into his eyes,” says Lewis. “He has an uncanny ability to connect with people, which we needed because August doesn’t speak much; he lets others talk, and takes it all in.”

This quality proved essential, adds Sheridan, as “August draws out the truth and humanity from the people he encounters. People who look into his open, honest face find themselves looking into a mirror. He reflects back to them what they had forgotten or don’t want to see, and it was truly remarkable to see Freddie accomplish this with such apparent ease. “He had a strong instinct for the role. For example, he kept August quite low-key when he wasn’t playing music and then, when he picked up an instrument he would suddenly come alive with electricity and his smile would be radiant,” Sheridan continues, adding that in a few instances where their approaches to a scene differed slightly she opted to let him play it as he felt and was not disappointed.

“August is not quite normal in his interactions with people,” Highmore observes. “He tends to stare. Kirsten and I decided it’s as though he never learned the social convention to politely look away, so he stares the way a much younger child might do and in the same calm, open and fearless way.”

Highmore, who could play clarinet and read music prior to the project, enjoyed the guitar work particularly and declares conducting the most challenging of his on-set lessons. “There’s a seven-minute symphony I have to conduct, and it’s amazing how involved that can be: you have to know the exact place to bring in the oboe on the left or the violas on the right and time the beats so you don’t mess up. Of course, if I did it wrong it wouldn’t have mattered that much; it only had to look real, but I wanted to get it as near to perfect as possible.”

At the same time, says Lewis, “Keri Russell learned to play cello from a dead stop. She didn’t play a note when we started this movie, and we gave her arguably three of the most intricate pieces ever written from Tchaikovsky, Elgar and Bach.”

Russell, who devoted herself to learning the solos, describes the process as “going from ‘Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star’ to Bach in twelve weeks. We broke the pieces down and slowed them so I could learn the correct bowing positions and then gradually brought them up to speed. Fortunately, they’re not relying on me for the sound—that will be some brilliant professional cellist—but it took intense practice just to achieve that visual credibility.

“It’s easy to see how the demands of a concert career can impact a person’s life,” she continues. “For a young virtuoso who started playing at an early age, it can be a strange world. I don’t think Lyla had much of a childhood or the regular ‘kid’ experience. She lived in her own world. Her whirlwind romance with Louis was such an incredible connection and a meeting of soul mates, that suddenly her reserve was gone and it was like a revelation. But, just as quickly, it was taken from her. Ten years later she’s like half a person. That spark is gone.”

Still, she says, “Lyla finally chooses to be brave. It may have taken her ten years to get back on track but she does it with passion. Once she learns she has a son, her story really begins.”

Says Sheridan, “I didn’t want Lyla to be the kind of girl who was just beautiful and gazed demurely out of windows. Certainly she has been sheltered by the kind of life she’s led but this is a woman with a steel spine. She has drive and focus. I wanted to see her get angry when she learns the truth and discovers she’s been cheated out of the love she deserved and then find a way to get it back. Keri has that classical, ethereal beauty and the grace and poise you would expect to see on stage at Carnegie Hall, but she delivers the rest of it, too. Lyla begins as a kind of china doll and ends up a fighter.”

Lyla’s initial reserve and formality provides a dynamic counterpart to Jonathan Rhys Meyers’ Louis, whose energy Richard Lewis describes as “raw and instinctual, a bad boy with heart.”

“It’s a role that could easily have gone down a self-indulgent path but Johnny does not allow that. He never turns it into ‘poor me.’ It’s a heartfelt, vulnerable role and he understood it perfectly,” says Sheridan.

“I liked the idea of playing a father who doesn’t know he’s a father and, more importantly, a character whose main concern is not himself,” says Meyers. “Working with Freddie took me back for an instant to that sense of fearlessness and freshness I felt when I was his age and it was delicious.”

The character Louis sings three songs on screen, each an original composition written expressly for the film by renowned musicians John Ondrasik, Chris Trapper and Lucas Reynolds. Rather than cast a musician who could act, the filmmakers sought an actor who could sing because of the depth of the material, and planned to enhance his voice in studio later, should he prove not to have the pipes. Producer Lewis recalls his relief and delight when it became obvious that Meyers was a dual talent. “When he came in to record the John Ondrasik song ‘Break,’ Ondrasik was on hand and said, ‘As long as he has the right attitude, we can fix it.’ Music producer Phil Ramone said, ‘As long as he gives us something to work with, we can fix it.’ Then Johnny sang and he was great and Phil looked at us and simply said, ‘You are so lucky.’”

For the role of Wizard, Lewis turned to Robin Williams, with whom he had recently worked on “House of D,” citing Williams’ ability to “bring lightness to roles that are not especially light and vice versa. He conveys the complexity of the roles so deftly.”

Maxwell “Wizard” Wallace is the personification of complexity. Father figure, mentor, headmaster, boss and agent all rolled into one, he is a homeless former musician who has taken possession of a condemned theater in the city where he holds court over dozens of street performers—offering guidance, discipline, shelter and protection… at a price, namely: “no play, no pay, no stay.”

Says Lewis, “There’s a real edge to Wizard’s personality. I wanted him to be unpredictable, scary and wonderful. You never know what you’re going to get with him, and that’s what makes him such a compelling character. Music is his only way of really connecting. It’s probably the one thing he did well in life, but he’s lost it and is desperate to get it back.”

Speculating on Wizard’s back-story, Williams suggests, “He was a promising musician himself, then fell through the cracks. I imagine years of abuse or neglect, then he just lost it, hit the wall, or maybe he just didn’t have enough talent. Now he finds himself working with these kids, trying to impart to them his understanding of music, but not many of them get it until August comes along. Right away, Wizard knows there’s something extraordinary abut this kid: he has the gift. In one way, he wants to nurture it, but he’s jealous too. More than anything, I think, he’s afraid the teachers and the world in general will beat the gift out of August the way they did with him.”

“August reminds Wizard of the best that music can be. Also, he reminds Wizard of who he once was—his own talent and promise—and that stirs very mixed emotions,” says Sheridan. Highmore jokes that Williams’ casting meant he “wasn’t the only kid on the set,” adding that his collaboration with the multi-talented actor helped develop his own improvisational skills and proved a learning experience as much as it was fun. “The way Robin works the dialogue it’s more like a conversation. It feels more natural and even when he took us off the page, I would find myself talking and answering questions in the way that August would answer them. Robin became Wizard and I became August. It was fantastic. He’s so good at it; I just tried to follow his lead.”

The film also alludes to a possible history for social worker Richard Jeffries, played by Terrence Howard, that adds depth and dignity to the character without spelling anything out. “Maybe he was a foster child himself and finds some solace in reuniting other lost children with their families,” Howard speculates. “A good portion of my roles have been tough, disreputable characters so it was nice to play someone who is closer to my heart. I know that a missing child is a reality for many people, and I feel for them as a father myself. It’s not hard to imagine the things that could happen.”

When Jeffries interviews August at the orphanage, says Howard, he sees that “August doesn’t fit in. The kids think he’s strange, but he knows he has a purpose.” During the meeting, which involves going over standard questions for the social worker’s case file, Jeffries attempts to encourage August to be more receptive to the idea of being adopted, by reminding him that there is a whole world waiting for him outside.

“As self-possessed as August seems, Jeffries understands—or suspects, because he’s likely seen this a hundred times before—that this child resists adoption because he fears that his successful placement will prevent his family from finding him,” says Howard.

“It’s at this juncture,” says Lewis, “that August first realizes he could go beyond the boundaries of the orphanage instead of merely waiting to be found. That one remark helps set August’s journey into motion.”

Similarly, Lyla’s father Thomas, played by William Sadler, sets her journey into motion when he finally reveals to her the life-altering truth that her baby boy survived.

“Thomas is flawed but not a one-note bad guy,” offers Sheridan. “We imagined a past for him that involved losing Lyla’s mother, a concert cellist herself. All he had left was Lyla. His decision to give her child away and keep the truth from her was not only a selfish attempt to keep her with him and manage her career, but it was also what he thought best for her as a father. Unfortunately, he was trying to push her into being something she wasn’t.”

Sadler sees the character as a catalyst, observing that “Thomas is integral at both turning points in Lyla’s life. First, when he’s hustling her into the car for her next performance and she sees Louis running toward her, she makes the split-second decision to stay with her father and that changes everything with Louis. Secondly, when Thomas finally tells her the truth, after ten years of her living under the shadow of this decision and the tragedy of thinking she’d lost her child, it sets her on an immediate search to find this child and, in the process, reclaim her life.”

Joining the “August Rush” main cast in the role of Arthur is Leon Thomas III, best known for his work on Broadway. Arthur is the young street musician whose guitar playing in Washington Square captures August’s attention upon his arrival in New York City and who leads him to Wizard. “Arthur is a real street kid,” says Sheridan. “He’s sharp, confident, a real wheeler-dealer with plenty of attitude, but August brings out his vulnerability and kindness. Later, when Wizard is so impressed by August’s ability that he focuses all his attention on him at Arthur’s expense, it truly hurts him.”

Another youngster who figures prominently in August’s journey is Hope, a choir soloist whose clear voice draws August into a Harlem church one night when he’s lost in the city for the second time. Hope is played by Apollo Kids Talent Search winner Jamia Simone Nash, just nine years old at the time of filming and already adding numerous television roles and singing engagements to her credit. It’s not long after befriending August that Hope brings his prodigious talent to the attention of Reverend James, played by Mykelti Williamson (“Forrest Gump”). After August’s impromptu organ concert reveals his astonishing ability, the reverend feels a moral responsibility to help him develop this gift.

The Music Factor

“The music is all around us. All you have to do is listen.” – August Rush

Music plays a fundamental role in “August Rush.” Two years before production, the filmmakers began reaching out to numerous artists and music industry professionals for original material that would help tell their story. The result is an eclectic, dynamic soundtrack featuring more than 40 pieces of music that run the gamut from a lone harmonica solo to a full symphony orchestra. It incorporates classical, rock and gospel performances, in harmony with a comprehensive score by Grammy Award winner Mark Mancina that charts the turning points in the lives of August, Louis and Lyla, and culminates in a stirring orchestral piece called “August’s Rhapsody” which weaves all of it together.

Toward that end, they hired not one but three music supervisors—Jeff Pollack, Julia Michels and Nashville’s only female music supervisor, Anastasia Brown—to pool their talents, contacts and expertise.

Says Pollack, “The music in ‘August Rush’ is a significant part of the continuity and flow of the story, which is why Richard got so many people involved. We had to be sure all the elements were connected in a way that worked.” Throughout the process, the music supervisors collaborated closely with each other and with Kirsten Sheridan and Richard Lewis in suggesting songs and artists, auditioning, playing pieces for one another and voting on selections. “It was an ongoing, coast to coast, collaborative process.”

Their challenge was not in gathering existing material that might be fit into sequences, but in finding artists who might compose and/or perform songs for specific scenes or characters. “Not just a collection of songs, but each one with meaning and relevance,” notes Michels. Without a movie to show at the time, this involved circulating the script and describing the story to prospective musicians.

One of the many who were touched by the story and offered an original composition was multiple Grammy Award winner John Legend, a child prodigy himself, who wrote and performed the evocative “Someday” that plays over the end credits. It is the first time the platinum-selling artist has ever written for a film.

Jonathan Rhys Meyers performs three songs that are meant to be the work of his character, Louis, and therefore had to be original. Reflecting his state of mind at three different points in his life, each was commissioned from a separate source to best capture that progression. Meyers explains, “The song ‘Break’ was from the period before Louis met Lyla. It’s confident and impetuous, the energy of a 19 year old in a band who has come over from Ireland to make it in the American music industry. ‘This Time’ has a haunting, more subdued quality, timed to the period after they are separated. The last one, ‘Something Inside,’ reveals a more mature Louis coming to terms with himself as an adult, as someone who realizes he’s been denying his destiny for a long time and finally has the courage to move forward again.”

“Break” was written by alternative rock singer-songwriter John Ondrasik (Five for Fighting), who also provided an existing piece, “King of the Earth.” “This Time” was contributed by Chris Trapper, formerly of the alternative rock band The Push Stars, and the poignant “Something Inside” came from Lucas Reynolds of Nashville’s pop/rock group Blue Merle. “In each case,” notes Anastasia Brown, “the musicians worked from their impressions of the script and were absolutely open-minded and collaborative. They wanted what was best for the film.”

Meyers did his own singing, but studio musicians provided the sound of the band backing his vocals, while actors and additional musicians were hired to play those parts onscreen. Similarly, professional musicians provided the music for the scene in which Louis and August, unaware of each others’ identity, share a spontaneous guitar duet in the park. Because August is a raw talent whose playing is instinctive, it was determined that his fret work would have to be out of the ordinary. Rock and Roll Hall-of-Famer David Crosby, who lends vocals to the soundtrack and whose “incomparable perspective,” says Lewis, “contributed greatly to the credibility of the music from beginning to end,” suggested that he approach the instrument in the style of acclaimed guitarist Michael Hedges.

“It’s more rhythmic and percussive than traditional strumming, and likely what someone like August might do when he picks up a guitar for the first time,” Sheridan describes Hedges’ innovative style. Part of Freddie Highmore’s guitar training included studying tapes of the late Hedges’ performances.

Brazilian guitarist Heitor Pereira composed the piece Highmore and Meyers are seen playing in the park, entitled “Dueling Guitars,” performed by Pereira and Doug Smith and produced by Mark Mancina.

Declares Lewis, “It’s essentially a father talking to his son without words. It’s almost like a parent bird feeding a newborn chick in the nest; it’s squawking and the chick chirps back, and they learn to communicate.”

In another scene, August wanders into Harlem and is viscerally drawn to a church by the soulful sounds of a choir—and in particular the powerful voice of a young soloist. It’s not only the music that touches him but the words she sings, which are about rising above loneliness by turning your loss into beauty and song.

The song, “Raise It Up,” is one of several written and performed for “August Rush” by Harlem’s Impact Repertory Theatre, with the addition of actress/singer Jamia Simone Nash, who performs the solo. It was produced by Columbia University film school professor and Impact founder Jamal Joseph and jazz/R&B musician Charles Mack, who also sings with the choir. Among those who participated in bringing these diverse sounds together was legendary record producer Phil Ramone, an eight-time Grammy Award winner whose 50-year career includes collaborations with some of the biggest stars in the industry. Ramone, who played violin and piano before kindergarten and studied at Juilliard while still in high school, identified with August’s ability to hear music in nature and ambient noise because he experienced sound in much the same way.

“Phil is so attuned that he can feel it in his body if something sounds right or wrong,” marvels Sheridan. “For him, it wasn’t about the album or the songs themselves, it was about how they melded into each scene. We had to be constantly aware of the visuals and the emotional content we were matching.”

The same was true for Mark Mancina’s score, with one significant distinction: in this case, it was Sheridan who was often trying to guide the action to match the musical timing, which was created first. Traditionally, composers begin scoring a film when it is nearly complete, taking some of their cues from the temp music and determining what the filmmakers are trying to convey. Because of the nature of this story and the vital, cumulative role the music plays, it had to be approached differently.

“It was a different way of looking at a film and a score, and quite intimidating,” says Mancina. “Because all the early themes had to interweave and make sense pulled together at the end, I had to write the end first and move backwards. I must have worked out 70 versions of the structure, it was that complicated. Ultimately, I put the script up on the computer screen and moved the corresponding music up and down alongside it so you could tell what would be happening with each piece.

“To establish a connection among the three central characters, I used a three-note theme that plays for August, for Lyla and for Louis at different times throughout the story,” the composer continues. “That theme was part of a larger recurring theme representing the music that comes to August in overtones, which are those notes that most closely approximate the vibrations of nature. The movie begins with an overtone and ends with one.”

Another recurring melody is Van Morrison’s haunting “Moondance,” first heard when Louis and Lyla meet, then again when Wizard plays for August. The third time it is magically and surprisingly transformed into a classical waltz, echoing through the grand musical finale in New York’s Central Park.

The Tempo Of New York City

“New York City is a living entity,” Robin Williams attests. “It’s possible to shoot movies in other places and finesse it to look like New York. Toronto can look like New York, but if you’re actually shooting a scene in Columbus Circle, Central Park, Washington Square, if you’re in Brooklyn or the Village or Manhattan, as soon as you step onto the street you know it’s a whole other game. That’s vital to a film like this; it’s all about rhythm and pulse.

“Washington Square has a great tradition of busking and performance, whether it’s musicians or chess hustlers,” he continues. “We’d be on the set all day with the kids playing their instruments and then break for dinner, and when we came back there would be genuine street kids out there with their own instruments.”

Adds Lewis, “Washington Square and Central Park, while also beautiful, can be easily dark and oppressive also, depending on your mood and circumstances.” “Robin, of course, would entertain the entire park full of people between takes. He had a thriving stand-up routine on the side,” recalls Sheridan.

Mindful of mood, production designer Michael Shaw and the filmmakers selected the film’s numerous practical locations to illustrate the stark contrasts that define August’s experience in the city. Offers Shaw, “It’s not an easy place, but it makes you tough to live there. As August feels that, we want the audience to feel it also. At the same time he’s taking in the glamorous New York iconography, the clean lines and elegance of places like Carnegie Hall and Juilliard, he’s also seeing the city’s rougher side, like the abandoned theater that is essentially Wizard’s lair.”

The production crew discovered an old but working theater for sale in the Bronx and transformed it into a derelict version of the Fillmore East, complete with faded marquee and posters and oversized speakers in the back. “We removed the seats, aged it down and decayed it,” says Shaw, whose work draws upon years of experience as a sculptor and painter. After welding a series of ramps and substructures that resembled makeshift scaffolding and decorating the walls with graffiti, he and his team “brought in props to look like the kids had created a home for themselves from whatever items they could salvage from dumpsters and the street—bits of wood, old doors, police barricades, whatever they could find. The trick was in making it look flimsy and slipshod, as though constructed by kids, yet have it be strong and safe enough for the cast and crew to walk on and move around.”

“It’s kind of a fairytale tree house structure that kids would fantasize about building, because they’re so resourceful and imaginative, but with an eye toward efficiency, which is how Wizard runs the place,” notes Sheridan.

Filming outdoors in New York required not only careful planning but a measure of luck, which remained consistently in their favor, as Sheridan relates with a touch of lingering amazement. “At one point we needed snow for a scene upstate when August is at the orphanage. It was February but there was no snow until the day before we traveled. Then, suddenly, they had the most massive snowfall that area had seen for something like 20 years and we had our beautiful red barn covered with white.”

The biggest challenge was the film’s climactic scene set at a symphony concert in Central Park, involving more than 500 extras and scheduled for an April shoot. Says Sheridan, “It was a huge risk but Richard is a fantastic risk-taker. He knew he just had to go for it, and it turned out that we got the four warmest nights in the history of April in New York City.”

“Everyone said you can’t do it, forget about it, move it inside,” the producer admits. “But that wouldn’t work. It had to be Central Park. This child has been searching for a way to reach as many people as possible, to go beyond the borders of any building and fill the air with music in the hope that his parents will finally hear him. We could not take this indoors.”

Says Sheridan, “The final rhapsody incorporates all the themes and the music August has heard or created, plus everything he has experienced in his emotional journey. It recalls the sounds that have impressed and influenced him, from the wind in the wheat fields to the church organ and Wizard’s harmonica.”

“It also integrates Lyla’s complex cello compositions and Louis’ guitar riffs, referring to August’s musical heritage,” says Lewis. “Assimilating all these themes with all the music of August’s imagination and experience is what the story is about.”

Production notes provided by Warner Bros. Pictures

August Rush

Starring: Freddie Highmore, Keri Russell, Jonathan Rhys-Meyers, Terrence Howard, Robin Williams

Directed by: Kirsten Sheridan

Screenplay by: Kirsten Sheridan, Richard Barton Lewis, Nick Castle, Jim Hart

Release Date: November 21, 2007

MPAA Rating: PG for some thematic elements, mild violence and language.

Studio: Warner Bros. Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $31,664,162 (48.5%)

Foreign: $33,614,408 (51.5%)

Total: $65,278,570 (Worldwide)