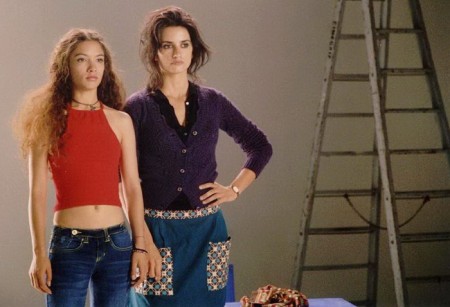

Madrid. Today. Raimunda is a young mother, hard working and very attractive, with an unemployed husband and a daughter in mid-adolescence. The family finances are very shaky, so Raimunda has got several jobs. She is a very strong woman, a born fighter, but also very fragile emotionally. She has kept a terrible secret to herself since childhood.

Her sister Sole is a little older. Timid and fearful, she makes her living with an illegal (undeclared) hair salon. Her husband left her and went off with a client. Since then she has lived on her own.

Paula is their aunt. She lives in a village in La Mancha where the whole family was born. A village swept by the east wind, the direct cause of the high rate of insanity registered there. That damn wind is responsible for the many fires that devastate the area every summer. The parents of Sole and Raimunda died in one of those fires.

A Sunday in spring, Sole calls Raimunda to tell her that Agustina (a neighbour in the village) has phoned to tell her that their Aunt Paula has died. Raimunda adored her aunt, but she can’t go to the funeral because moments before getting the call from her sister, when she had just come back from one of her jobs, she had found her husband dead in the kitchen, with a knife stuck in his chest. Her daughter confesses that she killed him because he had got drunk and kept making sexual advances to her.

The most important thing for Raimunda is to save her daughter. She still doesn’t know how, but what she certainly can’t do is accompany Sole to their aunt’s funeral in La Mancha. Sole reluctantly goes back to the village on her own. Among the women who accompany her at the wake she hears rumours that her mother (who died in a fire with her father) came back from the other world to look after Aunt Paula in her final years, when she was ill. The neighbours talk quite naturally about the mother’s “ghost”.

When Sole returns to Madrid, after parking her car, she hears noises coming from the trunk. A voice calls to her to open it and let her out, and says that she’s her mother.

Sole is terrified at first. The knocking from the inside the trunk continues. Sole opens it and discovers the ghost of her mother in there, surrounded by bags. She doesn’t dare even look at her, but when she manages to overcome her fear she sees that the ghost is just as her mother was in life, except that her hair is almost white and unkempt and her skin is paler.

She brings her upstairs to her apartment, and asks her how long she is going to stay. For as long as God wills, the ghost answers. Given the range of that reply, Sole has got no choice but to live with her mother’s ghost and let her get involved in the work in the hair salon. She introduces her to the first clients as a Russian beggar she met on the street and took in out of charity. When there are clients, the mother doesn’t speak, she just washes their hair and smiles.

Sole doesn’t dare tell her sister about the situation she’s in. For her part, Raimunda only tells her that Paco, her husband, has left her and that she has a feeling he won’t be back. Really, she is trying to get rid of his body, but she can’t find the right moment because she has got a new job that pays well and also offers a possible solution to her pressing problem… (what to do with the body).

The untenable becomes routine. Each of the two sisters takes a leap in the dark, surviving situations that are very tense, melodramatic, comic and also very emotional. Both women resolve them with audacity and by telling endless lies.

“Volver” is a story of survival. All the characters are fighting to survive, even the grandmother’s ghost. The grandmother’s ghost tells Sole that she wants to see her daughter Raimunda, and her granddaughter. She has to talk to Raimunda. In fact, that conversation is the reason she has come back from the other world… and that supernatural urgency has to do with the secret that Raimunda has hidden since she was a child. She doesn’t tell Sole this.

But Raimunda has a very strong character, she isn’t as soft as Sole and she doesn’t believe in ghosts, not even when she finds her mother hiding under the bed, in Sole’s house…

All this is just the beginning of a story that is complex and simple, touching and atrocious, one that affects the women in Raimunda’s family, the neighboring women and a few men.

“Most of the writers I know are very interested in films. Some of them are friends of mine. My assistant, Lola, sent the screenplay of Volver to Juan José Millás and Gustavo Martín Garzo. Their replies are in among what follows (words which they never imagined I would use parasitically in the press notes).”

From: Juan José Millás

To: Lola García

Re: Volver

Dear Lola,

I read the script in a heartbeat. The hyperrealism of the first scenes places you in an extremely emotionally tense situation. `Hyperrealist’ painting has been given that name because they didn’t know precisely in what way it differs from realist painting. In this country, we have always confused realism with the portrayal of local customs. Flemish painting is hyperrealist because it is fantastic, because it places us in a dimension of reality that allows us to be surprised by utterly quotidian situations. Once Pedro has placed us in that situation at the beginning, which is resolved with the appearance of the ghost in the trunk of the car, he can do whatever he wants with the viewer. And that’s what he does. Volver is a constant narrative sleight-of-hand, a conjuring trick. And you never know where the trick is.

In this script, there isn’t a single frontier that Pedro hasn’t dared to cross. He moves like a tightrope walker along the line separating life from death. He mixes narrative elements from seemingly incompatible sources with an amazing naturalness. And the more elements he adds, the greater the internal logic of the story…

P.S. While reading “Volver”, I couldn’t help recalling Pedro Páramo. Rulfo’s novel has got nothing to do with Pedro’s script, except in the naturalness with which both manage to have the dead co-existing with the living; the real with the unreal; the fantastic with the mundane; the imagined with the experienced; sleep with wakefulness. Reading the script, as when reading Rulfo’s novel, the reader is constantly in a dreamlike state. He is awake, of course, but trapped in the dream that is the story he holds between his hands. The strange thing is that Rulfo’s novel is furiously Mexican in the same way that Pedro’s script is furiously Manchegan…

Shooting

“The most difficult thing about Volver has been writing its synopsis. My films are becoming more and more difficult to relate and summarize in a few lines. Fortunately, this difficulty has not been reflected in the work of the actors, or of the rest of the crew. The shooting of “Volver” went like clockwork.

I guess I enjoyed it more because the last shoot (Bad Education) was absolute hell. I had forgotten what it was like to shoot without constantly feeling as though I was on the edge of the abyss. This doesn’t mean that Volver is better than my last film (in fact, I’m very proud of having made Bad Education) just that this time, I suffered less. In fact, I didn’t suffer at all.

In any case, Bad Education confirmed something essential for me (which I had already discovered on Matador and Live Flesh): you can never throw in the towel. Even if you’re convinced that your work is a disaster, you have to keep fighting for every shot, every take, every look, every silence, every tear. You mustn’t lose a drop of enthusiasm even if you’re in despair. The passing of time gives you another perspective and sometimes, things weren’t as bad as you once thought.”

Confession

“Volver (meaning `coming back’) is a title that includes several kinds of `coming back’ for me.

I have come back, a bit more, to comedy. I have come back to the world of women, to La Mancha (this is undoubtedly my most strictly Manchegan film, the language, the customs, the patios, the sobriety of the facades, the streets paved with cobblestones).

I am working again with Carmen Maura (after 17 years), with Penélope Cruz, Lola Dueñas and Chus Lampreave. I have come back to motherhood, as the origin of life and of fiction. And naturally, I have come back to my mother. To come back to La Mancha is to come back to the maternal bosom.

While writing the screenplay and during the shoot, my mother was always present and very close. I don’t know if the film is good (it’s not for me to say), but I’m sure that it did me a lot of good to make it.

I have the impression, and I hope it’s not a fleeting feeling, that I have managed to slot in a piece of the puzzle (the misalignment of which has caused me a lot of pain and anxiety throughout my life, I would even say that in recent years it had damaged my existence, and taken on far too great a significance).

The piece of the puzzle that I am talking about is “death”, not just my own and that of my loved ones but the merciless disappearance of everything that lives.

I have never accepted or understood it. And that puts you in a distressing situation when faced with the increasingly rapid passage of time.

The most important thing that comes back in Volver is the ghost of a mother who appears to her daughters. In my village those things happen (I grew up hearing stories of apparitions), yet I don’t believe in apparitions. Only when they happen to others, or when they happen in fiction. And this fiction, the one in my film (and here comes my confession) has produced a serenity in me the likes of which I haven’t felt for a long time (really, serenity is a word whose meaning is a mystery to me).

I have never in my life been a serene person (and it’s never mattered to me in the slightest). My innate restlessness, along with a galloping dissatisfaction, has generally acted as a stimulus. It’s only in recent years that my life has gradually deteriorated, consumed by a terrible anxiety. And that wasn’t good either for living or for working. In order to direct a film, it’s more important to have patience than to have talent. And I had lost all patience a long time ago, particularly with trivial things which are what require most patience. This doesn’t mean that I have become less of a perfectionist or more complacent, not at all. But I believe that with Volver I have recovered some of my “patience”, a word which naturally involves many other things.

I have the impression that, through this film, I have gone through a necessary period of mourning, a painless mourning (like that of the character of Agustina the neighbour). I have filled a vacuum, I have said goodbye to something (my youth?) I hadn’t yet said goodbye to and needed to, I don’t know. There is nothing paranormal in all this. My mother hasn’t appeared to me, although, as I said, I felt her presence closer than ever.

Volver is a tribute to the social rituals practiced by the people of my village with regard to death and the dead. The dead never die. I have always admired and envied the naturalness with which my neighbours speak of the dead, cultivate their memory and tend their graves constantly. Like the character of Agustina in the film, many of them look after their own graves for years, while they are alive. I have the optimistic feeling that I have been impregnated with all that and that some of it has stayed with me.

I never accepted death, I’ve never understood it (I’ve said that already). For the first time, I think I can look at it without fear, although I continue to neither understand nor accept it. I’m starting to get the idea that it exists.

Despite being a non-believer, I’ve tried to bring the character (of Carmen Maura) from the other world. And I’ve made her talk about heaven, hell and purgatory. And, I’m not the first one to discover this, the other world is here. The other world is this one. Hell, Heaven, Purgatory, they are us, they are inside us – Sartre put it better than I.”

Letter From Gustavo Martin Garzo

Dear Pedro, I really liked the script of your new film. Everything in it seems very familiar to me, very much you. It reminds me of the world of What Have I Done to Deserve This?! But it is less baroque, there is a transparency in it that situates us again in that world, it couldn’t be otherwise, but at the same time in a different way – more poetic, wiser, more touching. That mixture of horror and happiness is wonderful. As if your characters could always find in the midst of hell, as Calvino wanted, that which isn’t hell, and they’ll always manage to make it last in their lives. That mixture, so typically yours, of candor and perverseness which makes the most dreadful things funny, and manages to find beauty and hope in places they couldn’t possibly exist, seems to me one of the most marvelous things in your films.

Your script reminded me of a story that Tolstoy tells somewhere. A priest visits an isolated monastery in the Greek islands and finds four monks. He discovers that they don’t know the Our Father and, shocked, he teaches it to them. Then he takes his leave of them. When he is far from the coast he sees something gliding rapidly across the water towards his boat. He looks harder and sees that it is the monks whom he has just visited. They are running over the water! When they catch up with him they tell him they have forgotten the prayer he has just taught them, and ask him to repeat it. The priest, filled with emotion, replies that they don’t have to remember it, they don’t need it.

That is how the characters in your film seem to me. They come to us, vulnerable and lost, to ask us for help, but they do it running over the water. They don’t realise, but that is the strange, wonderful path they follow to reach us. And then, what can we tell them? That it doesn’t matter what happens to them, what they suffer, what strange, terrible things may happen to them, we are not the ones to judge them. What’s more, they are the ones who could judge us, even though we know they never will, because they aren’t obsessed with justice but with love. And the best thing they can do is to continue being as they are.

That is how I see this script, like a tale. There are terrible things in tales: people being chopped up, fathers who want to sleep with their adolescent daughters, children who are abandoned in a forest, fierce creatures who devour human flesh… The most extreme has a place in them, and yet, alongside that horror, there is always that rare thing we call innocence. It’s very hard to define what it is but there is nothing easier to identify when it appears. I think that art exists to pursue that innocence, which usually appears in the darkest places.

The River

“The happiest memories of my childhood are related to the river. My mother used to take me with her when she went to wash clothes there because I was very little and she had no one with whom to leave me. There were always several women washing clothes and spreading them out on the grass. I would sit near my mother and put my hand in the water, trying to stroke the fish that answered the call of the fortuitously ecological soap the women used back then and which they made themselves.

The river, the rivers, they were always a celebration. It was also in the waters of a river where, a few years later, I discovered sensuality.

Undoubtedly the river is what I miss most from my childhood and puberty. The women would sing while they were washing. I’ve always liked female choirs. My mother used to sing a song about some gleaners who would greet the dawn working in the fields and singing like joyful little birds. I sang the fragments that I remembered to the composer on Volver, my faithful Alberto Iglesias, and he told me it was a song from the operetta “La rosa del azafrán”. In my ignorance, I would never have thought that that heavenly music was an operetta. That is how the theme has become the music that accompanies the opening credits.

In Volver, Raimunda is looking for a place to bury her husband and she decides to do it on the banks of the river where they met as children.

The river, like the graphics of any transport system, like tunnels or endless passageways, is one of many metaphors for time.”

Genre and Tone

“I suppose that Volver is a dramatic comedy. It has funny sequences and dramatic sequences. Its tone imitates “real life” but it isn’t a portrayal of local customs. Rather it has a surreal naturalism, if that were possible. I’ve always mixed genres and I still do. For me, it comes naturally.

The fact of including a ghost in the plot is a basically comic element, particularly if you treat it in a realistic way. All of Sole’s attempts to hide the ghost from her sister, or the way she introduces her to her clients, give rise to very comic scenes.

Although what happens in Raimunda’s house (the death of the husband) is terrible, the way she struggles to keep anyone from finding out and the way she tries to get rid of him also create comic situations.

Mixing genres comes naturally to me but that doesn’t mean it’s free of risk (the grotesque and the grand guignol are always a threat). When you move between genres and go from one tone to its opposite in a matter of seconds, the best thing is to adopt a naturalistic style that manages to make the most ludicrous situation plausible. The only weapon you have, apart from a realistic setting, are the actors – the actresses, in this case. Luckily for me, they all exist in a constant state of grace. And they really put on a show in Volver.

Family

“Volver is a film about family, made with family. My own sisters were the advisers on what happened both in La Mancha and inside the houses in Madrid (the hair salon, the meals, cleaning materials, etc.)

Although they were luckier, my family, like that of Sole and Raimunda, is a migrant family which came from a village to the big city in search of prosperity. Fortunately my sisters have continued to cultivate the culture of our childhood and have kept our mother’s heritage intact. I moved away from home very young and became an inveterate urbanite. When I return to the habits and customs of La Mancha, they are my guides.

The family in Volver is a family of women. The grandmother who has come back is Carmen Maura, her two daughters are Lola Dueñas and Penélope Cruz. Yohana Cobo is the granddaughter and Chus Lampreave is Aunt Paula, who still lives in the village. This group would have to include Agustina, the village neighbour (Blanca Portillo), the one who knows many of the family’s secrets, the one who has heard so many things, the one who, as soon as she gets up, taps on Aunt Paula’s window and doesn’t let up until the old lady answers, the one who brings her a loaf of bread every day, the one who finds her dead and calls Sole in Madrid. The one who opens her home to the corpse in order to give it a proper wake until the nieces arrive. The one who converts her mourning for the neighbour into mourning for her own mother, who disappeared years before, she doesn’t know where. The character of Agustina is, in her own right, part of the family that is headed by Carmen Maura.

Agustina represents a very important element in this female universe: the solidarity of neighbourhood women. The women in the village spread out problems, they share them. And they manage to make life much more bearable. The opposite also happens (the neighbour who hates the neighbour and this hatred is passed on from generation to generation until one day a tragedy explodes and even they don’t know why). I have only paid attention to the positive part of that Deep Spain, which is what I experienced as a child. In fact, Volver pays tribute to the supportive neighbour, that unmarried or widowed woman who lives alone and makes the life of the old lady next door her own life. For a great part of her final years, my mother was helped by her closest neighbours.

Those women were the inspiration for Agustina, a magnificent creation thanks to Blanca Portillo. For me she is the real revelation because I didn’t know her.

I had only seen her in a play and I liked her but I couldn’t imagine that, with barely any film experience, she would be such a precise, polished actress, so overwhelming in her self-containment. Agustina, alone in the empty street, watching as Sole’s car disappears, is the image of rural solitude, stripped of all adornment. Blanca absorbed the essence of all the good neighbours in my village and made it her own.

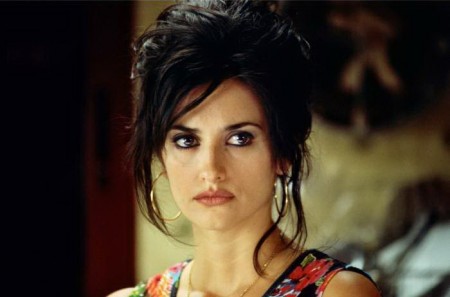

The Strength and Fragility of Penelope Cruz

And the beauty… Penélope is at the height of her beauty. It’s a cliché but in her case it’s true. (Those eyes, her neck, her shoulders, her breasts!! Penélope has got one of the most spectacular cleavages in world cinema). Looking at her has been one of the great pleasures of this shoot. Although she has become stylised in the last few years, Penélope showed (from her debut in “Jamón, jamón”) that she has more force playing plebeian characters than in very refined ones. Seven or eight years ago, in Live Flesh, she played an uncouth hooker who goes into labour and gives birth on a bus. They were the first eight minutes of the film and Penélope literally devoured the screen.

Her Raimunda in Volver comes from the same stock as Carmen Maura’s character in What Have I done to Deserve This?!, a force of nature that isn’t daunted by anything. Penélope can come up with that overwhelming energy, but Raimunda is also a fragile woman, very fragile. She can (and must, because of the script) be furious and a moment later, collapse like a defenceless child. This disarming vulnerability is what surprised me most about Penélope-actress, and the speed with which she can get in touch with it. There isn’t a more impressive spectacle than watching, all in the same shot, how a pair of dry, menacing eyes can suddenly start to fill with tears, tears that at times spill over like a torrent or, as in some sequences, only fill her eyes without ever spilling over. Witnessing that balance in imbalance has been thrilling. Penélope Cruz is a strong-minded actress, but it is the mixture with that sudden, devastating emotion which makes her indispensable in Volver.

It was a pleasure to dress, comb and make up the character and the person. Penélope’s body ennobles whatever you put on it. We decided on straight skirts and cardigans because they are classic garments, very feminine and popular in any decade, from the 1950s to 2000. And, it also must be said, because they reminded us of Sophia Loren, in her early days as a Neapolitan fishmonger. We have to thank the hairdresser Massimo Gattabrusi for the wonderful dishevelled hair-dos and Ana Lozano for the make-up. The extended eye-liner was a real find. There is just one false asset on Raimunda’s body: her ass. These characters are always big-assed women and Penélope is too slim. The rest is all heart, emotion, talent, truth, and a face that the camera adores. As I do.

The Return of Carmen

“I never imagined that there was so much expectation about our reencounter. I’m surprised by the number of people who told me how happy they were that Carmen and I were working together again! A song by Chavela says: `You always go back to the old places where you loved life’. That can also be applied to people.

There is always uncertainty, but fortunately Carmen’s disappeared at our first work meetings. There is a long sequence in the screenplay of Volver, almost a monologue, because only Carmen’s character (the grandmother’s ghost) is speaking. In this sequence, Carmen explains to her beloved daughter, Penélope Cruz, the reasons for her death and her return, over the course of six intense pages and six equally intense shots. This sequence is one of the reasons why I wanted to make the film. I cried each and every time I corrected the text (like the character played by Kathleen Turner in “Romancing the Stone”, a ridiculous writer of very kitsch, romantic novels who cried while she was writing).

The night we filmed it, the whole crew was aware of its importance. There was a lot of expectation. That made Carmen a bit nervous and she wanted to tackle it as soon as she could.

We took a whole night to film it and everyone from the trainee to me had that extreme concentration you get with difficult scenes and which precisely because of that makes them the easiest scenes, because we all give the most of ourselves.

Once again I felt that sacred complicity with Carmen, that marvellous feeling of being in front of an instrument that was perfectly tuned for my hands. All the takes were good, and many of them were extraordinary. Penélope is listening to her, at times with her head down. In the film, there is a lot of talking, there is a lot that is hidden and, for a comedy (so the crew says) there is a lot of crying.

From “Women on the Verge…” to the monologue in Volver, Carmen hasn’t changed as an actress, and it was wonderful to discover that. She hasn’t learned anything because she knew it all already, but keeping that fire intact over two decades is an admirable, difficult task that can’t be said of all the actors I’ve worked with.

The rest of the cast has been on a level with their companions. Lola Dueñas probably gives one of her most complex performances. She is the most eccentric of the four women in her family. Lola personally undertook to master the complicated Manchegan accent. She learned the secrets of the hairdressing trade and developed a comic streak unknown in her. She is intense, authentic and rare, in the best sense of the word.

Another of the blessings on this shoot was that all the girls lived and worked very closely. They had a wonderful relationship, like a family. And the lens captured that, too.

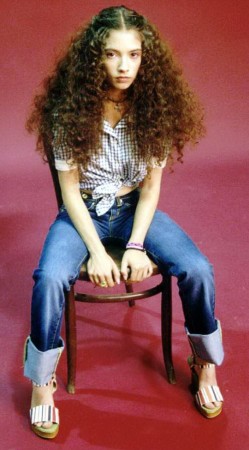

I’m very moved by young Yohana Cobo’s performance. She is present in almost all the scenes but as a witness. She does one of the most difficult things in acting, which is listening and being present. And her presence is eloquent while doing hardly anything. But Yohana’s work is conscious, subtle and very rich. Apart from “her” sequences, her monologue in front of her dead father… etc., the rest – always close to her mother, understanding her without knowing what is wrong with her- provokes a great tenderness in me. She also has an abrasive look. I hope everything goes well for her.

Chus Lampreave, María Isabel Díaz, Neus Sanz, Pepa Aniorte and Yolanda Ramos complete the cast, along with Antonio de la Torre, Carlos Blanco and Leandro Rivera.

José Luís Alcaine, behind the camera, Alberto Iglesias, with the music, and Pepe Salcedo, as editor, have once again tuned in to my secret intentions, each in his respective field.

These production notes provided by Sony Pictures Classics.

Volver

Starring: Yohana Cobo, Penélope Cruz, Carmen Maura, Lola Dueñas, Blanca Portillo

Directed by: Pedro Almodóvar

Screenplay by: Pedro Almodóvar

Release Date: November 3, 2006

Running Time: 111 minutes

MPAA Rating: R for some sexual content and language.

Studio: Sony Pictures Classics

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $12,899,867 (15.1%)

Foreign: $72,685,280 (84.9%)

Total: $85,585,147 (Worldwide)