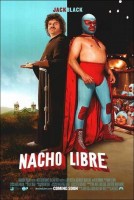

Nacho (Jack Black) is a man without skills. After growing up in a Mexican monastery, he is now a grown man and the monastery’s cook, but doesn’t seem to fit in. Nacho cares deeply for the orphans he feeds, but his food is terrible – mostly, if you ask him, a result of his terrible ingredients. He realizes he must hatch a plan to make money to buy better food for “the young orphans, who have nothing” (…and if in doing so Nacho can impress the lovely Sister Encarnación, that would be a big plus).

When Nacho is struck by the idea to earn money as a Lucha Libre wrestler, he finds that he has a natural, raw talent for wrestling. As he teams with his rail-thin, unconventional partner, Esqueleto (the Skeleton), Nacho feels for the first time in his life that he has something to fight for and a place where he belongs.

As Lucha is strictly forbidden by the church elders at the monastery, Nacho is forced to lead a double life. Disguised by a sky blue mask, Nacho conceals his true identity as he takes on Mexico’s most famous wrestlers and takes on a hilarious quest to make life a little sweeter at the orphanage.

“Before we made `Nacho Libre,’ I was really scared,” says Jack Black, who takes on his most eccentric and wildly comedic role to date. “I was thinking, `Oh man, what if I don’t pull it off? What if I get hurt? Holy crap, do I have to wear one of those super-tight unitard bottoms? Tights?! I’d rather be naked!’ But, you know what? That’s when it’s funny. When I’ve been really embarrassed and scared, that’s when things have turned out to be really good.”

About the Production

Black takes on the role of Nacho, a cook in a Mexican orphanage searching for his place in the world. The chance to work with director Jared Hess, whose first feature film was the independent smash hit “Napoleon Dynamite,” attracted the actor-producer to the project. “I loved `Napoleon Dynamite,’” says Black.

“Mike White and I were both excited by the the thought of working with him.” After speaking to Hess about an idea for a Lucha Libre wrestling picture, Black was in. “I told him, `If you’re at the helm, dude, I’m gonna suit up, because I wanna party with you.’”

Hess says he suspected Black’s excitement from the onset: “I think when Jack first heard about the idea that he’d be able to throw down in some tights and a cape, it was very appealing to him.”

“I don’t want to brag, but I’ve been told that I’m a natural luchador wrestler,” says Black. “I had the moves from the very beginning. Everyone asked me, `Did you study these moves?’ And I said, `No, why? Am I kick-ass?’ And they said, `You’re kick-ass.’ I think I have some inborn skills and I think maybe Jared sensed that and that’s why he wanted me to do this. I know he was thinking, `I would love to see J.B. throw down some hardcore, Lucha-style wrestling.’ It was meant to be.”

The film was written by Jared Hess & Jerusha Hess & Mike White, the last of whom is Jack Black’s producing partner at their newly formed production company Black & White Films and the writer of “The School of Rock.” “Nacho is a poor little orphan kid who’s stuck in a monastery, gets shoved into this life, and is never really accepted by the brothers in his church,” says Jerusha Hess. “They don’t respect him. He’s always felt a little put upon; when he decides to become a luchador, something awakens in him.”

From the very beginning, it was clear that only one man had the kick-ass comic skills, the boundless energy, and the physical build to bring Nacho to life. “In our first meeting with Jared, he said that he and Jack Black had already been talking and wanted to do a project together,” says producer Julia Pistor. “We thought if you put Jack Black in a mask, he’d still have such expression with just his eyes and eyebrows, it would be great and very funny. It all fit together perfectly.”

White, who co-wrote the film and serves as a producer, says that the filmmakers were motivated by the combination of elements that inspired the movie, from the true story that served as a jumping-off point to the classic Lucha Libre films with the immensely popular Luchadore, Santo. “Even though I wasn’t a Lucha Libre expert when we started, in retrospect, it all seems inevitable,” he says. “First, this story – which is inspired by a true story – of a guy who cooks for friars and orphans by day and wrestles by night felt like such movie material. Later, the more old Santo movies we saw, the more matches we went to, the more we saw that this was a colorful, comic world and how much fun it would be to have Jack as a huge centerpiece to it.”

Hess and the producers were confident Black could handle the Lucha ring. “Aside from being one of the best physical comedians, he’s actually also an incredibly agile and energetic man,” says Pistor. “If you’ve ever seen him singing and performing in Tenacious D, he’s all over the stage, doing acrobatics and crazy jumps. We knew he would be able to deliver the physical comedy and stunts.”

While it was clear that only Jack Black could play the lead role as the filmmakers envisioned it, they were also sensitive to the fact that they were telling a Mexican story with an Anglo in the lead. They were careful to write the role specifically for Black.

“Nacho’s mom was a Scandinavian missionary and his dad was a Mexican deacon. They tried to convert each other, but got married instead,” says White. “When they died, he grew up as an orphan. Even though he’s grown up, he’s still there, the fun guy among all the humorless, disciplinarian monks. He’s the buddy that these kids need in their lives.”

Black says that living and working in Mexico was the key to picking up the accent. “I pulled a Meryl Streep,” he says. “I worked hard to perfect my accent. I wanted it to be kick-ass, but it was not easy.”

In fact, Black jokes that his audible guideline for his accent came from the cinema. “I would think of Ricardo Montalban, especially his performance in `The Wrath of Khan,’” says Black. “I’m not trying to do an impersonation – it’s just something that I would think of for inspiration. I love Ricardo Montalban – he’s so dramatic!”

Kidding aside, White points out that Black came to the production prepared. “Jack speaks a lot of Spanish,” he says. “When he came down to Mexico, he quickly picked it up again, and he came to the first day of rehearsal with a fully born take on the accent.”

De la Reguera was impressed with Black’s accent and discipline. “He’s very professional,” she says. “Jack’s always thinking about the character. Because he has to have a Mexican accent, he’s very concentrated and focused all the time. Sometimes, I gave him tips that he imitated.”

“That guy´s a triple threat,” Hess says of Black’s comedic, athletic, and acting skills. “He´s a total genius. He´s very funny, a team player who has no ego and working with him is great. Everybody on the crew just felt like they could totally approach him. He was just such a fun, funny, happy-go-lucky guy.”

Pistor says that the scene in which Nacho’s secret is revealed shows off Black’s amazing acting range. “Jack’s depth and ability as a comedian and an actor are best shown in the fire scene,” says the producer. “As Nacho prays for God’s blessing on his upcoming wrestling match, his robe catches fire. After running out of the church and rolling on the ground, extinguishing the flames, Nacho’s robe has burned off from the bottom up, revealing his wrestling tights. It’s a hysterical image Jack’s standing there exposed to everyone. But, he then goes and delivers a speech that is so moving and so meaningful, it brings tears to your eyes. It’s a remarkable scene because it shows Jack as a funny, physical comedian, on fire, wearing a funny outfit, to a heartfelt speech about defeating Ramses and taking care of the orphans, all in one shot.”

Pistor found irresistible the idea of a guy who cooks for priests and orphans by day and wrestles at night. “I was drawn in by the incongruity of it all,” she says, and underlines that the first person that she and her team at Nickelodeon Movies thought of to direct the unique and funny story was “Napoleon Dynamite” creator Jared Hess. “We found `Napoleon Dynamite’ to be full of a lot of heart and we believed he was perfect for this story.”

“The idea just struck Jared as being so hilarious, he felt we could do this,” says Jerusha Hess. “My first impression of Lucha Libre was that it’s a funny mix of acrobatics, the circus, and the pro wrestling we know in America. It was funny and different from American wrestling.”

“It just hit me as something so strange and wild – it was a story I wanted to tell,” says Jared Hess. “The concept is so outrageous that it seemed like the perfect follow-up to `Napoleon.’”

“Jared’s got a mind for incredible, strange stories,” says Black. “He’s drawn to interesting, peculiar characters and people. And he’s populated the whole film with them. Every face is another amazing: `Whoa! Look at that guy!’ Everyone’s got a really funny, awkward story. That’s what I love about `Napoleon Dynamite’ and about this film, too.”

Part comedy, part drama, part high-flying wrestling action, “Nacho Libre” springs from the lively spectacle-sport it showcases, relying on Lucha Libre’s reality and myth, organic truths and fantastic creations. “No one’s ever seen a movie like this before,” says Black. “It’s hilarious, sweet, and totally unique.”

The colorful, bizarre, surreal world of Lucha Libre boasts a long history of legendary wrestlers with superhero names – El Santo, Blue Demon, Gory Guerrero, Tarzan Lopez, Superbarrio Gomez – and, in Mexico, the sport enjoys a popularity second only to soccer. During its Golden Age, from the late 1930s through the early 1980s, Lucha Libre dominated Mexican pop culture with its burlesque mix of costumed wrestlers, including women and midgets.

“Lucha Libre transcends the generations in Mexico,” says White. “There’ll be little kids, there’ll be old women jumping up and yelling, `Kill him! Kill him!’ Lucha brings the whole community together in ways that pro wrestling in the states doesn’t.”

Stories of luchadores rising from modest and impoverished beginnings, fighting their way to fame feeds the sport’s working-class mythology, symbolic pageantry, and accessibility. Throughout Mexico, at outdoor rings or arenas, in gyms and auditoriums, fans watch battles between tecnicos and rudos (“good guys,” “bad guys”), a morality play in the square circle, with self-styled gladiators seeking body slams and soap operatic salvation. An ostentatious mix of entertainment, athleticism and cathartic ritual, the world of Lucha Libre is both a diversion and an avocation for its fans of all ages and incomes.

“I’ve always been a fan of the Lucha Libre movies by Santo, who was kind of the Muhammad Ali of the Mexican wrestling world,” says “Nacho Libre” co-writer-director Jared Hess. “I was first exposed to the sport through the films of Santo, who made a number of really cool movies in the sixties and seventies. When the opportunity presented itself to do a film about the whole Lucha Libre world, I was really excited.”

Lucha Libre differs from American-style wrestling in its secret identities and must-see-live experience. “There´s something so mysterious and unique about Lucha Libre, comparing it to other forms of wrestling in the world,” says Jared Hess. “Luchadores wear masks to hide their identities and are very protective about that. I don´t think there was ever a photograph taken of Santo with his mask off. The other thing is Lucha Libre is something that you need to experience live. You need to see how quickly the fight moves from in the ring to the audience. It is something very unique to Lucha Libre: you need to be there.”

Lucha Libre lives large in Mexico and has a growing popularity in the United States via live shows such as Lucha VaVoom, which tours the country and regularly appears in Las Vegas. While some luchadores are chiseled to perfection, the lure and magic of Lucha Libre is the idea of the Lucha as the “every man.” With his true identity concealed under a mask, a luchador acts out for the masses, sending symbols of evil, corruption, and power crashing to the mat.

Nothing disgraces a luchador more than being unmasked in the ring. A fighter will do anything to protect his mask, and consequently, his identity. “A luchador never, never, ever takes off his mask. No one ever sees their faces. I don’t know if their wives do,” laughs de la Reguera. “If they take off your mask, you lose. You lose everything.”

Julia Pistor says that the combination of Jack Black, Jared Hess, and the weird world of Lucha Libre wrestling make the picture irresistible. “What is so great about `Nacho Libre’ is it doesn’t fit into any one box,” says Pistor. “It’s funny, bizarre, left-of-center, colorful, beautiful, and exciting.”

“We always intended to create a world you’ve never seen before and bring an original comic sensibility to it,” says White. “Our goal was a comedy with broad appeal, but with a unique filmmaker’s voice.”

About the Supporting Cast

With Black cast in the lead role, Hess stressed the importance of surrounding him with Mexican and Latino actors. Hess and his team held large open casting calls in Oaxaca, Mexico, to find the supporting actors and hundreds of extras needed for the film. “When we were in Mexico, we had access to some amazing people,” says Hess. “Shooting in Mexico added a production value that we could never have gotten anywhere else.”

Heading the supporting cast are Ana de la Reguera, a well-known telenovela star in Mexico, as the sweet, buttoned-up novice, Sister Encarnación; Héctor Jiménez as Nacho’s string-bean-skinny wrestling partner, Esqueleto; and Richard Montoya as Guillermo, Nacho’s rival for the friendship and approval of Sister Encarnación.

The event that spurs Nacho to become a luchador is the chance to impress Sister Encarnación. “Nacho is infatuated by Sister Encarnación, but everything that happens is very, very innocent and sweet,” says the director. “Nacho’s parents were religious missionaries who fell in love and got married when they were trying to convert each other. I think Nacho hopes, in the back of his naïve mind, that what happened to them could happen to him. He just really likes her and wants her approval.”

“Ana is angelic and beautiful, which is exactly what Encarnación needs to be, but she´s also very funny,” says Pistor. “You don´t always find that in one actress. She and Jack have great timing.”

“She’s very innocent,” says de la Reguera about her character. “She cares about the orphans and she’s trying to do the best, even though they are poor and have little. Nacho tries hard to impress her, he wants to help all the time, but he seems to always get in trouble.”

De la Reguera, who was born and raised in Veracruz, Mexico, began performing as a young girl. By the first grade, she was studying ballet and jazz, on her way to becoming an accomplished dancer. De la Reguera continued her studies, enrolling in theater at the Instituto Veracruzano de Cultura, where she was soon discovered and cast in the popular telenovela, “Azul.” She’s widely considered one of the best young actresses in Mexico.

De la Reguera says her role is to play it straight, which is tough when Black is in the scene. “He makes me laugh even more when we are in a scene than off-camera,” she says. “I have to be very quiet and calm, and it’s hard for me not to react when he’s making faces and doing weird stuff, even off-camera, because his character is doing these things. I have to react, but it’s hard for me not to laugh. So, I keep serious and when the scene ends, I’m laughing and laughing.”

“Ana is the perfect `straight man’ for Jack, but in real life, she’s got a wicked sense of humor,” says White. “On set, she was a real prankster – always up to mischief.”

Playing the role of Nacho’s wrestling partner, Esqueleto, is Héctor Jiménez, who the filmmakers discovered during an open casting call in Oaxaca. Though Hess knew right away that Jiménez had to have a role in the film, it wasn’t immediately clear that the filmmakers had found their Esqueleto. “After Héctor’s first audition, he was so talented I felt he had the potential to inhabit a variety of different roles in the film,” says Jared Hess. “In the end, we felt he would be amazing as Nacho’s tag team partner.”

“We met Héctor on our first day in Mexico, at the first casting session,” says White. “I’m really glad we made that decision – he’s so funny and brings so much to the movie.”

Jiménez fit the bill for the rope-thin, street-fightin’ Esqueleto; in fact, Esqueleto’s weight was originally estimated at around 150-155 pounds, but Jiménez was holding steady at 130 pounds. As a result, the actor’s arduous physical preparatory regiment consisted of doing nothing. “They told me to not train more than I did during rehearsals, because they did not want my muscles to have more definition,” says Jiménez. “I thought they were kidding me, but they were serious.”

Homeless on the streets of Oaxaca, the ever-hungry Esqueleto meets Nacho in an alley behind a restaurant, where Nacho goes to collect a bag of chips left out for the orphans. A fight ensues, which Esqueleto wins, taking the chips and fleeing like the wind. “Esqueleto kicks my ass – and I realize the guy’s a good wrestler. We form a partnership and we think we’re going to be the most unstoppable wrestling duo,” says Black.

Black agrees. “Héctor is an incredible comedic force. We were really lucky to find him,” he says. “We were auditioning a ton of people and he came in and blew us away. He’s so funny and he has such an expressive face. It’s kind of got a Laurel and Hardy action to it – I’m macho Nacho and he’s Esqueleto, the skinny guy.”

De la Reguera says she had a hard time not laughing at the sight of the two. “Héctor is very funny playing opposite Jack,” she says. “Jack is the big, wild and very masculine guy. Esqueleto is the opposite. He’s very skinny, a little bit feminine, and acts frightened. So, the comedy comes very naturally with these guys together. Héctor brought a lot of little, funny things to the role.”

From the first day the dynamic duo of Nacho and Esqueleto showed up on set, the laughter began. “The day they did the camera test, the first day in which Black and Jiménez wore their wrestling costumes, everyone on set just started laughing out loud,” says Jared Hess. “They were such an odd couple in their very tight revealing clothes.”

Filming in Mexico

One cornerstone of the film’s development was to film in Mexico with a local crew and a largely Mexican cast. “When we first spoke to Jared, we all agreed that we didn’t want re-create luchadores in America,” says Pistor. “We were committed to shooting the movie in Mexico. There’s an incredible film community down there and we were excited at what we could do.”

“Because we were able to shoot the entire film in Mexico, it’s very real,” says Jerusha Hess. “These are real people that you could never find in Hollywood. Everyone on the cast and crew was so excited about the movie, because it’s about showing the world their culture.”

One advantage that kept the production running smoothly is that the director speaks fluent Spanish, allowing him to communicate directly with his crew and cast. “From the first day we met, Jared spoke to me in perfect Spanish,” says de la Reguera. “Because he knows the language, and has lived in Venezuela and spent months in Mexico, he knows perfectly how we live. He knows the difference between Venezolanos, Colombianos, Argentinians, Mexicans. He was very respectful; that was so important.”

The film’s primary location was in the state of Oaxaca, located in southern Mexico. For thousands of years, Oaxaca’s extensive mountain systems (some 10,000-feet above sea level), tropical rain forests, deserts, and coastal lowlands created a geographic isolation, allowing indigenous cultures to flourish.

“It definitely helps to be immersed in the culture that you’re portraying in the movie,” says Black. “Oaxaca is gorgeous. It has ancient pyramids, amazing architecture, and a rich flavor that adds to the whole experience. I don’t think there’s ever been a comedy with as many beautiful backdrops before as we have in this film.”

“Jared chose Oaxaca on gut,” says White. “It showcased Mexico’s mountains and Mexican culture – it was a magical place. We had a charmed experience filming there.”

“Oaxaca is one of Mexico’s most beautiful places and one of our best-kept places,” says de la Reguera. “The indigenous people who live in Oaxaca are very intelligent and strong. We in Mexico are very proud of Oaxaca and the artisan traditions they keep.”

The region’s distinctive traditions and languages (approximately fifteen indigenous languages are still spoken today, including Zapotec, Mixtec, Mixe, etc.) have created a rich, complex cultural diversity unmatched in other portions of Mexico or Latin America. These co-existing civilizations, some dating back thousands of years, have produced generations of artisans, including entire villages that devote themselves to producing specific goods and handicrafts. Oaxaca is widely known for its world-class cuisine, its chocolate, chiles and moles, as well as its black pottery, ceramics, wood carvings, metalworks, textiles, basketry and stone work.

“In choosing a location, we were looking for finding a balance between the two worlds of the monastery and the Lucha Libre,” says the director. “Oaxaca fit perfectly into what we were looking for.”

Hess and his team found their monastery in Etla, an ancient town about 40 minutes in a valley outside downtown Oaxaca. The long-abandoned ex-convent Etla had the variety of rooms necessary to serve alternatively as interiors of the monastery and orphanage. Across the fields of Etla, on a sloping hilltop near the ex-convent, is the Santuario del Senor de Las Penitas, where an old church served as the exterior for the monastery. Production designer Gideon Ponte and his crew partially reconstructed the existing church belltower and extended the building with a multi-story faux stone facade to create the compound where Nacho and the orphans live.

Livin’ La Lucha Libre

Shooting in Mexico enabled the filmmakers to tap into the tremendous enthusiasm and love of the sport of Lucha Libre. “I think Lucha Libre is so popular because it’s kind of like going to the psychiatrist in Mexico,” says de la Reguera.“You go and laugh and yell and curse; people throw their fury on the Lucha, on the ring, in the stadium It’s very good for Mexican people that we have that tradition.”

“People love it. It´s like a communion,” adds Mexican actor Héctor Jiménez. “The crowd participates all the time, screaming, going crazy, involved with the wrestlers. It’s kids, old ladies, men, everybody.”

Hess and his team held large open casting calls to find the hundreds of extras needed for the film. “When we were casting in Mexico, the word got out pretty quickly that we were doing a Lucha movie; out of nowhere, there would be twenty luchadores that would just show up at the place where we were holding casting,” he says. “All kinds of wrestlers would show up. It was a surreal experience to see people that I´d seen in these classic Lucha movies come and want to participate in what we were doing.” Hess ended up with a core group of Luchas and professional wrestlers, ranging in age from 22 to 65, from Mexico City, Oaxaca, and the United States.

Luchadores come in all sizes, shapes and sexes. From the towering to the tiny, from the obsese to the muscle-bound, the variety of luchadores is endless. There’s a long-standing tradition of women luchadores as well as midgets, which are called “minis” and act as powerful battering rams against opponents.

“When you go to a couple of Lucha matches, you’re gonna see some incredible athleticism, and then you’re going to see some dude who’s super clumsy, lumbering around in a really crazy costume,” says Black. “At one match, I saw this huge dude, who did not really have skills, but it was still extremely entertaining. That made me feel confident; I may not be that dude who can bench-press 500 pounds, but I can be like that dude in the costume.”

Among the real-life luchadores in “Nacho Libre” are Oaxacans Agustin Rey Vasquez Lopez and Ricardo Javier Castilla Peña, who portray the Galindo Brothers. At 65, Vasquez, with his long, black hair, has been wrestling for nearly four decades.

Abelardo Hernandez (real-life Lucha name: “El Pandita”), who portrays Muñeco, Carlos Acosta Barroso (real-life Lucha name: “El Mimo”), who portrays El Pony, and Ignacio González Camarena (real-life Lucha name: “Iñaqui Goci”) who plays El Semental, are all wrestlers from Mexico City. The midget duo in the film, Satan’s Helpers, are also professional luchadores from Mexico City: Filliberto Estrella Calderon and Gerson Virgen López.

Playing Ramses, the most famous and feared luchador in Mexico, is professional luchador Cesar Gonzalez (real-life Lucha name: “Bronco”). It happened that a casting call was held in the wrestling arena in Mexico City where Gonzalez has his offices; as the day wound down, Gonzalez was making his way to his car when a casting assistant chased him out to the parking lot and urged him to do an interview.

“Ramses is number one, the champion, the richest, the best in professional wrestling,” says Gonzalez. “Everyone knows Ramses, since he is the creation of Senor Ramon, the most powerful man in wrestling.”

A professional luchador for twenty years, Gonzalez says going into wrestling meant going into the family business. “My real idol is my father,” says Gonzalez. “My father was a professional wrestler, and my brother, too. My father’s ring name was Dr. Wagner and my brother is Dr. Wagner, Jr. I feel so happy in this business because I feel it in my blood. It is never work.”

* * *

In summer 2005, Black threw himself into his training. “I’ve never done any other sports films, so I don’t know what other people’s trainings are like, but I felt I was going to actor’s boot camp,” he says.

“Jack trained a ton,” says White. “By the end of the shoot, he was in pretty good shape – he was pretty much a muscle-bound Luchador.”

“I’ve always liked to mix it up and get crazy and athletic once in a while,” Black says. “I don’t consider myself an athlete, but when I do my performances with my band, I always do a little bogus gymnastics and stuff. In preparing for the film, I knew they’re going to be flipping me and I’m going to be jumping through the air and doing karate chops and getting karate chopped and flipped and whatnot, so I got busy.”

Black studied in Los Angeles during the summer with a Lucha coach, learning all the basic moves and the language of the ring. He arrived in Oaxaca a few weeks before production began in October, to train and work on the fight choreography with Nick Powell, the film’s second unit director and stunt coordinator. A veteran stunt and fight choreographer, Powell has overseen some of the great cinema fights of all-time, including “Gladiator,” “Braveheart,” “The Last Samurai,” “The Bourne Identity,” and “Cinderella Man.”

“Nick did an amazing job of choreographing every fight in the film,” says Jared Hess. “He worked very, very closely with Jack to make sure that everything was safe, and that Jack was able to perform everything.”

“Nick just absorbed himself in the world of luchadores,” says Pistor. “He wanted it to be authentic, so he really studied the sport and brought a great group of luchadores and stuntmen to create the fights. If you look at the wrestling matches, they are true to the sport, but they are heightened with a Nick Powell spin.”

Black says he found the fight choreography process fun. “I was inspired by a lot of the moves that I saw in the Santo movies,” he says. “For the most part, Jared had all these funky moves that he had in his mind that he’d loved from seeing the movies and Nick, our stunt coordinator, also got super-creative. There are some moves in this film that have never been done in the Lucha ring.”

As signature moves are part of a luchador’s reputation, Hess, Black, and Powell and his team came up with a variety of moves. Basic wrestling move such as the lockup, headlock and body slam were combined with more exotic manuevers such as the Camel Crunch and the Puento Olympico. “Luchadores have different movements that they are known for,” explains de la Reguera. “They have names like `La Tuerca’ or `El Tornillo.’ It’s almost like dancing, a performance or circus thing. They are acrobatic movements.”

“I threw in a couple of moves of my own,” says Black. “One we call `the Anaconda Squeeze’ – that’s mine. Also the `Wind of a Lion,’ where I sit on my opponent’s face. It’s deadly.”

* * *

No luchador is complete without his mask and costume, so the filmmakers and costume designer Graciela Mazon took care to create an authentic and outrageous Lucha look. “With all the costumes in the film, we really tried to reflect the authenticity of what the whole world is about,” says Jared Hess. “We had a lot of fun coming up with all the different costumes for each of the different characters. These costumes are outrageous and cool because it is an outrageous world and sport.”

“The costumes are very bright and very kitsch,” says de la Reguera. “It’s a big performance, a tradition. People may think the costumes in the movie are an exaggeration, but they are not.”

For Black, wearing his Lucha tights brings back memories. “I think I wore tights in a play I did in high school, `Pippin.’ Not very macho. I wore tights and little, little dance shoes. Capezios. For `Nacho Libre,’ the tights are part of the deal – if you’re gonna be a Lucha wrestler, you got to slip into the tights.”

Black also took to waxing to project that masculine luchador image. “I noticed in all the Lucha photographs, all of the luchadores were hairless. So, I waxed,” he says. “I waxed it all off and then it grew back – and then I was told they couldn’t wax it because the hair has to be longer to wax. So I started shaving. It was a battle every day.”

Co-star Jiménez says wearing nothing but baby blue briefs and red boots can take some getting used to. “I felt like a sausage at the beginning,” he says about his skin-hugging, barely there attire. “But at the end of the movie, I loved the costume.”

A key part of any luchador costume is the mask. “When I put on the mask, then I become another man. It was a little bit like becoming a superhero,” says Black.

These production notes provided by Paramount Pictures.

Nacho Libre

Starring: Jack Black, Ana de la Reguera, Héctor Jimenez, Richard Montoya, Peter Stormare

Directed by: Jared Hess

Screenplay by: Jared Hess, Jerusha Hess, Mike White

Release Date: June 16th, 2006

MPAA Rating: PG for rough action, and crude humor including dialogue.

Studio: Paramount Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $80,197,993 (80.8%)

Foreign: $19,057,467 (19.2%)

Total: $99,255,460 (Worldwide)