For three decades, Michael Mann has remained one of the most compelling filmmakers, and his consistent level of artistry has created an indelible influence on cinema. His stylish, lasting dramas from Manhunter and Heat to The Insider and Collateral examine the complicated dynamic-and sometimes indefinite margin-between criminals and those struggling to keep one step ahead of them.

In 2006, Mann returns to the seminal franchise on which he first gained his reputation in television: Miami Vice. According to writer F.X. Feeney, in his book Michael Mann (Taschen, 2006), “After Collateral, Mann lost no time choosing Miami Vice as his next project.

What attracted him to the original teleplay in 1984-the reality of life undercover-he finds no less compelling in our new, `globalized’ millennium.” Mann’s interest in telling the story of a dark world connected through “multi-commodity,” continues Feeney, lies in the fact that “drugs, weapons, pirated software, counterfeit pharmaceuticals, even human beings are all routinely trafficked and sold.”

In the mid-’80s, the television series Miami Vice, with a brilliant pilot screenplay written by the show’s creator Anthony Yerkovich, arrived and created a tectonic revolution in television. Drawing its creative inspiration from Mann’s work, Miami Vice became one of the most groundbreaking series in television history, pioneering a new way in which televised dramas were conceived and staged. As Film Comment critic Richard T. Jameson remarked at the time, “It’s hard to forbear saying, every five minutes or so, `I can’t believe this was shot for television!’”

Now, the filmmaker comes back to his “new Casablanca,” Miami, where third-world drug running intersects with the billion-dollar corporate-industrial complex-for the first postmillennial examination of what globalized crime looks and feels like-with a big-screen contemporization of Miami Vice, one unrestricted by the limitations of television. The roles he helped to create of Miami vice cops “Sonny” Crockett and Ricardo Tubbs are inhabited by Colin Farrell and Academy Award winner Jamie Foxx, who both underwent extensive training and simulations by undercover officers from the DEA, FBI, ATF, Miami-Dade Police Department (including S.W.A.T.) and Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE)-people who themselves tread the dangerous world of trafficking.

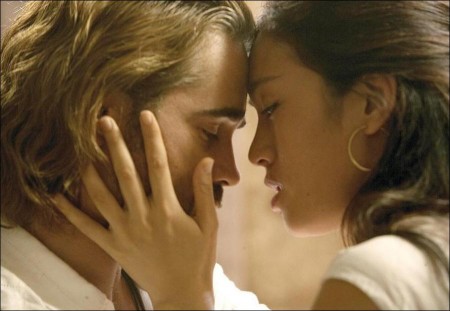

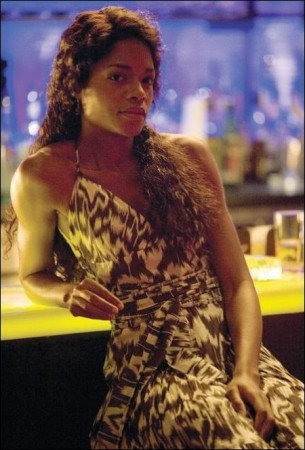

During the hunt, the partners encounter the cartel’s beautiful Chinese-Cuban financial officer Isabella (Gong Li, Memoirs of a Geisha)-a woman who moves, launders and invests money. The seductress provides Crockett a way of exorcising his own demons as he tries to keep her safe from darker forces… while the new lovers learn just who’s playing (and falling for) whom. Simultaneously, the stoic Tubbs infiltrates the elusive criminal enterprise while keeping a protective eye on his intel-analyst girlfriend, Trudy (Naomie Harris, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest).

As Crockett and Tubbs work undercover transporting drug loads into South Florida, they race to identify the group responsible for their friends’ killings while jointly investigating the New Underworld Order. During their mission, lines will get crossed as the partners start forgetting not only which way is up, but on which side of the law they’re supposed to be…

Supplementing the five-star cast, supporting players who join Mann in Miami Vice include Ciaran Hinds (Munich) as FBI Special Agent Fujima, Justin Theroux (Mulholland Dr.) as fellow vice cop Zito, Barry Shabaka Henley (Collateral) as Lieutenant Castillo, Elizabeth Rodriguez (Dead Presidents) as Detective Gina Calabrese, John Ortiz (Narc) as drug middleman José Yero and Luis Tosar (Cargo) as the stateless plutocrat (and Isabella’s pygmalion) Montoya.

About the Production

“Death is not procedural or casual, not when it’s somebody you know.” – Michael Mann

The reasons for returning to Miami Vice are, according to Michael Mann, simply, “attraction and timing.” “It’s the allure of doing undercover work and what happens to you…that was my central interest. When I first read Tony Yerkovich’s screenplay for the original Miami Vice pilot, my instinct was to make this as a feature film. But it had already been committed to NBC as a television series.”

Several decades, and countless fans and critical nods for his films later, Mann knew that it was time to fully explore the characters he had painstakingly developed and make a film that “liberates what is adult, dangerous and alluring about working deeply undercover… especially when Crockett and Tubbs go to where their badges don’t count.”

Mann welcomed the challenge of uncovering the “bad things that happen in dangerous places” with a feature film. He relates, “As an R-rated feature, we can explore some of the things we couldn’t in television. There was always the sense of some self-imposed restrictions because we were a series. There’s a whole sensual life that’s there-for Crockett and Isabella, for Tubbs and Trudy.

Of utmost importance to the writer / director / producer was his desire to tell the primary arc of these agents’ stories: what happens when operatives go so deep undercover to infiltrate crime syndicates that they struggle to make it back to reality? He feels that’s where the key dramatic opportunities lie…in telling the filmic versions of Crockett and Tubbs’ immersion into danger.

“You really are out on the edge, surviving by your wits,” Mann notes. “One of the terms used for it is `enhanced undercover’… particularly when you are infiltrating a criminal organization that has a lot of counterintelligence resources. You can go too deep-and it happens frequently-and you have to rely on your partner to pull you back from the edge.

Mann all too well understood that it takes a special kind of individual to work undercover or “U.C.” To authoritatively dramatize the reality that Crockett and Tubbs face, one of the first orders of business was to secure expert advice for his script development and production decisions. According to real-life undercover cops and technical consultants on the film, the majority of people who do undercover work grew up at the crossroads of good and evil. That would need to be duly highlighted to make Miami Vice’s world legit.

“Undercover means that you have to assume a different identity,” notes one. “You can’t have the mannerisms that you normally have as a law enforcement officer. You have to act, talk and walk like a bad guy. And you have to convince the bad guy that you are not a cop because that’s the first thing they’re gonna look for.”

Miami Vice would also offer Mann the chance to spend time exploring the city he helped tattoo on America’s conscience in the ’80s. “The allure of Miami has sustained itself in my imagination,” he notes. “The city has a perfumed reality, where things are not exactly what they seem. It’s very attractive, alluring and sensual; it’s also very dangerous.”

It is, indeed, a place the filmmaker calls “not the southernmost tip of the United States, but rather the northernmost tip of South America-a banking capital for cash money.”

It was vital to Mann that he capture the allure of Miami coupled with its gritty underbelly…his trademark stamp when constructing realism for his films. To capture the extreme stress and drama of real undercover work-living a fabricated identity-he would need to go to lengths to prepare his cast for their roles, and that would include the development of elaborate life histories, realistic simulation of buys and smuggling, and extensive physical and mental training.

Script in hand and experts at the ready, Mann knew it was now time to cast the men and women of his Vice unit… once again.

The Players Club: Cast of Miami Vice

“The best undercover identity is oneself with the volume turned up and restraint unplugged.” – Michael Mann

Known for drawing performances that allow his actors to take their craft to a new level, Mann wanted to fill the roles of the Miami-Dade police, feds and their quarry with men and women who were as dedicated to understanding the back stories of their characters as they were to performing on screen. He knew that to realize these cops or criminals would require rigorous training and strict discipline on the part of his cast.

Also crucial to Mann was designing a production that had a multicultural look and feel…mirroring the players in his intersection of the third world and global conglomerates. Discussing his leads, Foxx, Farrell and Li, Mann shares, “Working with actors like Jamie, Colin and Gong…the level of aggressive ambition in how far we can take it is what makes the experience of directing exciting and adventurous.”

Mann’s choice of Jamie Foxx to portray Ricardo Tubbs taps into a relationship that goes back several years between the actor and filmmaker. Miami Vice is the third collaboration between the two, following 2001’s Ali and 2004’s Collateral, for which Foxx was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. In that same year, Foxx was nominated for and won the Best Actor Oscar for his work in Ray.

Mann relates, “Jamie is a genius at using mimicry as a means to get to an immediate, spontaneous, truthful place with moment and character. He knows the demeanor that Tubbs should have, and he goes all the way with it.”

In developing the urbane and dead-smart Tubbs, Foxx describes his method as “working with the characteristics of a person. I have to see someone and watch them, because I already know what I want to do with the character.” Training with the actual undercover cops he met to prepare for his role, Foxx spoke openly with the officers about the trappings of the occupation. “You’re tempted to do this and you’re tempted to do that,” he discovered-asking of them, “Do you taste the other side?”

According to the actor, straddling the line between the job and what the underworld exposes you to is “like being married, and you’re having an affair. You are married, but you are dating the wild side over here.”

Bringing life to the charismatic and flirtatious Sonny Crockett, a role he-like millions of other fans-originally knew from the ’80s television series, would be Colin Farrell. The Irish native, fresh from starring in two epics, Oliver Stone’s Alexander and Terrence Malick’s The New World, would settle easily into the role of Southern-bred Crockett. Farrell succinctly notes, “Crockett is a good guy; he is as solid as a rock.”

The actor would come to share his director’s passion for research and preparation. Of finding his character, Farrell says, “The amount of information that Michael had to offer all of us was amazing. We went everywhere to find Crockett…Atlanta, Memphis and parts of Texas. We studied who his father was, that his mother died pretty young. I reviewed reels of information on the clothing of the time Sonny was born-what the number one shows, movies and music were. It permeates through you and affects your choices.”

Of Farrell, Mann comments, “Colin is just courageous, in upper-case letters, and comes at it from a place of complete classical training. He’s fueled by a fearlessness to go where his character has to.”

The actor, according to Mann, “brings an entirely new character to the same role of Sonny Crockett. Nothing undoes what Don Johnson did, which was great. This is an additional iteration…no comparative context applies.”

Commenting on his co-star’s performance, Foxx says, “I believe that Miami Vice is his chance to really take that persona people see and marry it with Crockett. Colin’s got the macho good looks, the sense of humor, but he has this sense of `get down.’ When he does it, you think, `This is for real.’”

The leads knew that they had to get to know each other well to pull off believable roles as partners. As Foxx explains about the partnership, “It’s all about chemistry. You don’t have the chemistry, you don’t have anything.”

Farrell agrees, “There is a deep kind of friendship and understanding that is born of sharing a lot of the same beliefs…just being there for each other and trusting one another.”

The primary feminine element in Miami Vice is the financial criminal/object of Crockett’s obsession, Isabella, portrayed by highly respected Chinese actress Gong Li. Already established as a popular film star in Asia, Li has recently turned her talents toward a film career in the West through starring roles in Memoirs of a Geisha and the upcoming Young Hannibal.

“This character is very different,” notes the actor. “She is quite distinctive. You can’t say that she’s a villain, but she is a drug smuggler. She’s a strong person, but at the same time, a truly vulnerable one.”

Mann shares, “I’ve wanted to work with Gong since I saw her in Raise the Red Lantern and Red Sorghum. The more difficult things become, the better she likes them.”

Li lauds Mann for pushing her beyond her own self-imposed limitations. “He assigns impossible tasks for you to complete, but he tells you that you are able. In the end, you really do achieve it.”

A key plot point to Isabella’s story is her unexpected romance with Sonny Crockett, complicated by the fact that she is involved with Montoya-played by noted Spanish actor Luis Tosar-one of the most powerful criminals in Latin America. Crockett, too, does not honestly represent himself to Isabella. This love, established under the pretense of false identities, will play itself out with inherent problems.

Another welcome addition to the multicultural cast was British actor Naomie Harris as Bronx-born intel analyst (and Tubbs’ lover) Trudy. Catching the eye of audiences worldwide in 2002’s sleeper hit 28 Days Later, Harris played double duty on this production. When not on the set of Vice, she was shooting scenes for the second and third Pirates of the Caribbean films for director Gore Verbinski.

Equally comfortable with her razor-sharp dialogue as she was with her handgun training, the actor impressed Mann from day one. “Naomie is brilliant. She has a voracious appetite for acquiring skills,” he states.

Supporting the company are Justin Theroux as the partners’ fellow vice cop Zito, Barry Shabaka Henley as their direct report Lieutenant Castillo and Elizabeth Rodriguez as sharpshooter Detective Gina Calabrese.

Rodriguez also took Mann’s boot-camp mentality to heart. Watching her prepare for a scene in which she stands off against the Aryan Brotherhood for a sniper shot, Mann commends, “Elizabeth became kind of a killer working with consultant Mick Gould in the gym.”

Completing the core cast in Miami Vice are New York actor John Ortiz (Narc, Carlito’s Way) as the calculating drug runner José Yero and Ciaran Hinds as FBI Special Agent Fujima-the man who reluctantly allows Crockett and Tubbs to penetrate further into the drug underground after their friends are killed.

Players in place, Mann and crew began the critical training to mold his actors into hard-core cops and duplicitous criminals indigenous to this world.

Gritty Reality: Training with Experts on Set

“That’s the sound of air rapidly filling the vacuum created by your departing body.” – Ricardo Tubbs

To have his cast members be able to walk the line between justice and revenge, Mann saw to it they prep through a regimen of physical, mental and weapons training before shooting began. He notes that if anyone understands this kind of training, it is an actor. “Agents prepare to go undercover in the same way an actor prepares-knowing everything about the person they are pretending to be,” he relates. “They isolate themselves and focus in.”

To become the elite detectives Sonny Crockett and Ricardo Tubbs, Farrell and Foxx would receive three months of preparation on-site in Miami. Fortunately, the two actors had their fair share of experience with drills. With Farrell’s recent training time on S.W.A.T. and The Recruit and Foxx’s 2005 work on Jarhead and Stealth, the new partners were up for the challenges that would come in shooting the film.

With cooperation from multiple consulting officers in local and federal law enforcement, Mann developed a strict program for his talent. He exemplifies this necessity in noting, “When Crockett and Tubbs meet José Yero and they’re negotiating about the way they run loads in, Colin and Jamie really could do all of those things they’re talking about doing.”

Farrell recalls, “We drilled and drilled…going out to the gun range four times a week for two hours a day and shooting off about 500 rounds per day. We were shown tactically how you hold a gun, how to lessen yourself as a target and how to have synchronicity and economy of movement that would allow you to take out your target.”

Mann would also ensure that his core cops were instructed on how to live the U.C. life. “We were in some scenarios that were routine `buys’ on a street level,” he reflects. “And then, we would move product from offshore-on boats and planes-simulating these experiences for Jamie and Colin with people who had done this many times.”

The filmmaker describes his staged rehearsal scenes as “street theater, but for real. We were with seven, eight, nine major law enforcement people from federal law enforcement who did major undercover work of a very enhanced, very dangerous nature in foreign countries and the U.S. Some of the scenarios got stunningly real.”

This was welcome, albeit exhausting, news for Foxx and Farrell. Farrell echoes the team’s respect in commenting on his tutors, “These guys have gone deep. Working, buying, transporting drugs from South America through Miami. Some of them did it purely for the rush. They have back stories they’ve developed-fabricated identities where they’ve created an absolute alternate existence.”

The actor continues, “Michael doesn’t have people working on his films who say `in theory.’ They are all very practiced in what they do or have done. He’s all about, `Why fake it when you can do it for real?’ They get 10 minutes to convince somebody that they’re the real deal and that they’re there to buy or sell product. The downside of a bad take for them isn’t a shift in direction or mood for the scene-it’s a bullet in the head.”

Mann approached seasoned Federal agents early in pre-production about helping to train actors for Miami Vice on methods of conducting undercover work. One technical consultant notes, “Colin and Jamie were basically put through the same scenarios that our guys would go through, and these scenarios were done by agents that do actual undercover work.”

One example of this training involved Farrell’s accompanying undercover officers on what he believed to be a real drug deal. It was explained to the actor that everything dangerous had already taken place and he was assured “nothing’s gonna happen.”

In fact, the scenario was set up so one of the fake dope dealers could test Farrell’s skills as Crockett by completely overreacting in front of Farrell. According to one of the Federal officers, “We actually had [our undercover guy] jump out the window when the guys showed up. Colin saw this chaos happening right in front of him, and you see him backing away from the deal. I mean, for a split second, he’s like, `Oh my God, what have I gotten myself into?’”

But, ultimately, the Federal agent gives Farrell credit for “using his skills to try and get out of the situation. I kept insisting that he was a cop and said, `Prove to me that you’re not a cop! Show me if you’re wearing a wire! And Colin rips his shirt open goes, `Look, I’m not a cop. I don’t have any wires.’” After that, the officer notes that the scenario played out successfully, with Farrell learning that in the world of U.C…anything can happen anytime.

Farrell recalls that the exercise gave him, “a real sense of it…regardless of how much you think you may be prepared for something, in the spur of the moment, the odds shift and the nerves kick in. It was very scary, because for all intents and purposes, this was the real deal.”

Mann offers of his unique training, “If Colin feels competent that he can really do what Crockett does, then it increases his self-efficacy. And how good he knows he is invests moments magically with believability. He is Sonny Crockett. And he can do everything Sonny can do.”

Regarding his actors’ drive to become immersed in their roles, Mann knew that-while he wanted reality captured-his first priority was to make the set painstakingly safe for his stars. When charging through South Florida’s coastline highways, “Colin is really driving the Ferrari,” he shares. “We put Colin into a Ferrari Challenge Car-a race version of 360-complete with roll cage and racecar levels of protection. If I’m going to have him driving the car, I want him driving that car as if he’s a skilled driver and everything he’s doing is second nature.” What Crockett does, Tubbs must, so it was the “same with Mojo, the boat,” Mann says. “Jamie got great at driving that boat as the throttle man and he took off and loaded a small plane.”

The Intersection of Crime: Shooting Locations for Vice

“We didn’t bring you here to kill you. If we wanted you dead, you’d be no longer drawing breath in Miami.” – Isabella

In 2006, while many a director has settled for green-screen technology or cheaper locales to lens his or her story, Mann has resisted and rejected those cheats. For the filmmaker, it is crucial to go to the actual places where his characters live, work and play. “There are things you can’t artificially create,” he says. “As good as our crews are, you can’t duplicate the texture, the fabric of the neighborhoods. Audiences know when you’re making it up, and they know when you visually deliver an animated environment for the actors that makes it feel like they are truly here.”

Mann and his location team aggressively searched out territories around the world that duly reflected the mood of the scenes they needed to film. The lion’s share of Miami Vice was filmed in Miami and Key West, Florida, with forays into Paraguay, the Dominican Republic, Uruguay and Brazil.

The city of Miami has changed considerably since the early 1980s when Mann’s television series helped to usher in a new generation of Miami tourism. Recently off his Oscar® win for Memoirs of a Geisha, Australian cinematographer Dion Beebe would rejoin Mann for Vice. The Collateral director of photography poses that Miami is in great transition. “I think it’s hard at times to define,” he feels. “Miami is a city that is finding itself.”

Miami has grown vertical in style with numerous high-rises now dotting the horizon and construction occurring everywhere citizens and tourists look. Discussing the new Miami, Mann explains that the city is more cosmopolitan, affluent and sophisticated than what he saw during his television series’ shooting days. “Miami is now much more muscular. It’s extremely different than it was in the ’80s-the `new architecture Miami’ is a city about transparency. You see the storm systems forming out over the Bahamas and look out glass walls high in the air. You’re at one with nature and have a sense of being elevated right over Miami Harbor.”

Despite the four or five storm fronts that could come through daily in August 2005, Farrell found the jewel of South Florida gorgeous, describing it as “a lake with coins that have been thrown on the water and float to the surface.”

Hurricanes Katrina, Wilma and Rita became unwelcome visitors to the set of Vice while the crew was filming throughout the Caribbean. While not causing damage to the areas in which they were shooting, the hurricanes remained a somber reminder to the cast and crew of the devastation happening throughout the Gulf region of the U.S. The production lost seven days of shooting due to the ferocity of the storm systems, but fortunately, never had to shut down completely. “It impacted us, but was trivial compared to the loss of life and devastation suffered by so many in the southern part of the U.S,” relates Mann.

Notes Farrell, “The hurricanes were so powerful and awe-inspiring. But the damage they caused… it was just so horrific.”

Foxx recalls happier moments of his time in South Florida suggesting, “People will want to see the Miami that Michael gives them in this film…the boats, the planes, the brand of what Miami actually is.”

Design notwithstanding, Mann knew this was still a place with amazingly dark stories to tell. He doesn’t lean on the tried-and-true South Beach images of ’80s pastel, but features the fresh look of the city that explores not only the extraordinary houses and high-rise condominiums, but also its less scenic underbelly.

The desire to capture that grit of the drug underworld throughout the film would lead his production team out of the U.S. and to multiple locales in the Caribbean, as well as central South America, Paraguay.

One of the opening sequences of the film begins with a courier delivery in an unusual place. Mann opted to shoot the sequence in Ciudad del Este (CDE), Paraguay, which has a look like no other spot in the world. The city, based solely upon commerce (not all legal), is compared by some to an anthill with its claustrophobic swarms of people carrying on their business. There is an inherent, dangerous aroma to the town, and the multiple ethnicities of the community add to its mystique. Beebe and Mann were adamant about capturing that on film.

Aptly described by Mann as “capitalism gone amok,” Paraguay would offer the players the perfect backdrop for key sequences. With its “laissez-faire commerce and a whole city selling anything and everything,” Mann dryly notes, “I bought Collateral for two dollars on DVD.”

In the coastal city of Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic, Mann used specific parts of the region (the eastern half of this Caribbean island) to double as Haiti, a country far too dangerous in which to film. To enhance the ambience of a tension-filled night scene, Mann chose the Capotillo-more specifically, the Mercado Nuevo-the most dangerous part of the city in which to work.

Elaborate security measures had to be taken in both of these locales, and the cast and crew felt the added realism when shooting the scenes. Stephen Donehoo, managing director of Kissinger-McLarty Associates, was hired by the production as the political advisor on Vice. “Some of the places where this movie is filmed include very interesting countries where moving political situations require a degree of finesse,” notes Donehoo. “We worked closely with federal and local governments to show that what we’re doing is useful for that country.”

Mann describes Haiti, the noted haven for drug traffickers, as “chaotic and very difficult to infiltrate. Trafficking organizations run their businesses in smart, sophisticated ways. [As an undercover agent] you may easily find yourself, as Crockett and Tubbs do, in a negotiation in Haiti.”

Within these locales, Mann’s production design team set about adding details that bring further intensity to each scene of Miami Vice. To turn Santo Domingo into their choice city in Haiti, the team changed all the signage in the scenes from Spanish to French. Specificity in color, too, was vital for accurate representation of Haiti. Of the design he wished to capture in the island nation, the filmmaker says, “There’s something stunning about color choices that people paint on buildings in Haiti, and it doesn’t look like anywhere else.”

When considering locations to lens the Havana sequences where Crockett and Isabella engage in their taboo romance, Mann recalled the similarities of Havana to a coastal city south of Brazil he visited on a trip to Montevideo, Uruguay, many years earlier. He directed the art department to build a house in the Atlantida area of Uruguay to duplicate Vedado, a neighborhood that runs along the northern shore of Havana. It would prove to be quite a challenge to make this home believable, both inside and out.

“It’s Isabella’s family home,” explains set decorator Jim Erickson. “With the exterior, Mann wants to say she doesn’t want to stand out because she is in the drug trade. But, on the interior, he needs to keep it simple and maintained because Isabella would most definitely have the money to do that.”

Lensing Miami Vice: Allure of High-Definition Cameras

“We illuminate Montoya’s operations from the inside. No one has ever tread before where we are now.” – Sonny Crockett

Director Mann has become a pioneer in his use and support of high-definition filmmaking. The depth-of-field that HD shooting allows-together with its system for exposing highlights-created a dimensionalized effect for Mann and cinematographer Dion Beebe. Vice would mark a reunion for the two, as they worked together on Mann’s last thriller, Collateral.

For Mann, being able to offer this HD spectacle to the audience is all part of the rush. “I confess, there’s an adventure in doing this,” he says. “When people say, `That’s too difficult, you can’t take camera systems and put them in an offshore power boat and make the cameras work and shoot dialogue scenes at 70 mph in the middle of the ocean,’ you start figuring out how to do just that.”

The primary reason for filming in HD is, according to the filmmaker, to allow the audience “to feel how the light hits the water and these people…to feel how saturated and vivid everything you’re looking at becomes.”

Beebe notes of filming on location in HD, “You have to respond to your environment a lot. And that can often surprise you, whether it’s the light or a dramatic moment with the sky…some interior or background actions that wouldn’t have happened in a controlled back-lot situation.”

Mann both traveled to exotic foreign locations and used every corner of Miami to bring the high-def stickiness, heat, threat and feel of the tropics to this film. Vice relishes the rumbling thunder and sheet lightning that warn of approaching hurricanes as well the explosions of real gunfire and the sick, thick impact of bullets. Beebe knew from his experience on Collateral that what his team was shooting for this film would be very close to what the audience would see on screen. Trying to re-create that signature look in post-production is technologically challenging.

The cinematographer found himself confronted with new obstacles to conquer on his sophomore project with Mann. “Collateral was certainly my first endeavor with HD,” Beebe says, “and Michael’s aim was to really push the sensitivity of these cameras shooting at night. Eighty percent of Miami Vice is night work, but the point of departure from Collateral was taking HD into our day work.”

Beebe explains that the HD cameras were tested beyond their normal use during the production. “We’re shooting on high-speed racing boats, Ferraris, at sea on freighters, Lear jets and in small airplanes. It’s just been this barrage of activities, and the cameras have taken quite a beating.

“I think they’re still a little bit fragile and essentially designed for studio work,” he continues. “But we got through it…although it was a real challenge for our digital crew to keep up.” All was forgiven, however, once Beebe took a step back and realized that with this technology he could see “inches in front of my face to infinity.”

One curious aspect of shooting with HD technology is its impact on the cast and crew. “It affects the dynamic on the set,” offers Beebe. “We’re used to working in film with 10-minute rolls; you stop, reset, reload and start again. But the 50-minute take is a reality now. You have your camera crews repositioning and the props department running. Everything suddenly becomes a lot more fluid because you are not resetting, starting again and cutting.”

Noting just how important HD is to getting the feel of his locations just-so, Mann states, “I can bring an audience in and make them feel like, `I am there. This is happening. I am on this boat at this time of the night or this early in the morning.’”

The cameras, coupled with on-location filming, allow Mann to get the exact emotions he wants to draw from his filmgoers. “You don’t feel the same way in Los Angeles as you do in Miami-because a hurricane is one day away (or just left) and the weather is stormy in the Caribbean.”

****

Revisiting the world Mann created by shooting the feature film Miami Vice was a cathartic experience for all involved, especially the writer/director/producer. He is keenly aware that fighting crime on this level is a gruesome business. With the feature, Mann doesn’t mythologize or glamorize what it’s like to traffic in this world. He makes us come to feel the dread, confusion and isolation of those on the front line.

That fascination with the world of U.C. has led the filmmaker to bring the story of two detectives who begin to forget “which way is up” to worldwide audiences. He offers, “There’s a high, a juice in doing it; that’s what really motivates people who go undercover. It’s that moment when you have put over this fabricated identity, and you’re living it, you’re feeling it and they’re buying it.”

Mann concludes, “I’m trying to locate an audience within the experience of `you are Crockett’ in these lethal circumstances.” Just as that pivotal moment in the film when, notes Mann, “Tubbs says to Crockett, `Are you aware that the badge is gonna come out, and the fabricated identity and what’s really up are gonna collapse in the same frame? Are you ready for that?’”

On July 28, 2006, audiences can answer just that question.

These production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

Miami Vice

Starring: Colin Farrell, Jamie Foxx, Gong Li, Naomie Harris, Ciaran Hinds, Elizabeth Rodriguez, Barry Shabaka Henley

Directed by: Michael Mann

Screenplay by: Michael Mann

Release Date: July 28th, 2006

MPAA Rating: R for strong violence, language and some sexual content.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $63,450,470 (38.7%)

Foreign: $100,344,039 (61.3%)

Total: $163,794,509 (Worldwide)