It is 1933, in Alabama. Manderlay is a plantation where a group of people are living as if slavery hadn’t been abolished 70 years earlier. Upon leaving Dogville in 1933, Grace and her father head far south to the state of Alabama where they arrive upon the bizarre place.

The second installment in Lars von Trier’s “USA — Land of Opportunities” trilogy. Dafoe will play the father of Grace, the central character played by Nicole Kidman in the series’ first film, “Dogville,” and played by Bryce Dallas Howard in “Manderlay”. The film, shot entirely on a stage, is set in the American South during the 1930s and explores the repression of blacks.

This is the strange, disturbing story of the Manderlay plantation. Manderlay lay on a lonely plain somewhere in the deep south of the USA. It was in the year of 1933 that Grace and her father had left the township of Dogville behind them, with Grace’s unforgettable verdict: ‘If there is any town the world would be a little better without, this is it’; and had driven homewards towards the city of Denver. But being away from home is a serious matter in the gangster business, and the mice had been well and truly playing while the cat was away.

Grace’s father and his army of villains had spent the entire winter seeking out new hunting grounds in vain, and now, in this early month of spring, they are driving south in one last attempt to find a favourable location in which to take up residence. By chance their cars stop in the State of Alabama in front of a large iron gate bearing a thick chain and a padlock. Beside the gate a dead oak tree towers over a heavy boulder with Manderlay hewn in monumental letters into the granite.

Just as Grace, her father and his men are about to leave after a short break and a quick lunch, a young black woman runs up to the car. She knocks on Grace’s window. She hammers at the glass in despair.

Grace gets out of the car, and ignoring the distinct advice of her father she follows the girl through the gates of Manderlay, and there she finds a group of people living as if slavery had not been abolished seventy years earlier, with white masters and black slaves.

Grace decides to intervene, despite the tentative warnings of the old house-slave Wilhelm, who sums up his fears for the future when he says: ‘At Manderlay we slaves take supper at seven; when do people eat when they are free?’

Grace can hardly believe what she now sees in the yard at Manderlay. A young black man, Timothy, has been tied between two fence posts for a whipping by a white overseer, Stanley Mays.

Grace orders him to desist, only to be confronted by the owner of the plantation, an elderly lady known as Mam, who points a shotgun at her. Her father’s henchmen take control of the situation. Mam, it turns out, is weak and dying. In her bedroom she begs Grace, as woman to woman and for the good of all, to destroy an old book hidden under her mattress.

Grace refuses to grant her wish. Mam dies and Grace discovers that the plantation has been run according to this handwritten book, Mam’s Law, seemingly a code of conduct and a dehumanised chronicle purporting to detail the appearance and behaviour of generations of slaves at Manderlay.

Grace truly believes that she has a duty to make it up to the slaves for injustices they have suffered at the hands of her kind: ‘we brought them here, we abused them and made them what they are’, as she argues to her father; and she decides that she will remain at Manderlay until she has seen them through their first harvest.

Her father grudgingly leaves her with four henchmen and a lawyer, warning Grace that he won’t be there to pick up the pieces the way he did in Dogville, as he hastens to remind her, when her plans for the redemption of Manderlay fall apart.

The task of winning the trust of the former slaves is an arduous one for Grace. That civilization takes time comes as no surprise to her, but it’s hard for her to be patient and remain passive rather than intervening and applying force to realize what is, after all, her noble desire to sow the seeds of democracy and pro-action amongst the former slaves. Yet gradually she makes herself understood.

After some setbacks, the crop is planted and the roofs of the dilapidated cabins are repaired. Reduced to the status of their former slaves, Mam’s heirs, the white family, are obviously unhappy with the new state of affairs, but among the black residents only handsome Timothy remains completely impervious to Grace’s enthusiasm for improvement

In her frustration, Grace succumbs to overwhelming erotic fantasies featuring this scion of African nobility (he is a Munsi, of a proud African tribe). But like Grace, Mother Nature also has plans for Manderlay.

The cotton crop is imperilled by a dust storm and its residents are threatened by famine. The gangsters grow bored and the former slaves are slow to learn the lessons of democracy on an empty stomach. Things deteriorate, and in order to survive they must eat dirt; the way slaves have done for so many years.

Then a horrible tragedy strikes. Claire, all skin and bones, and the young daughter of Jack and Rose, two of the former slaves, is found dead in her bed; most likely for lack of the food her parents refused to eat day after day, saving it for her. It turns out that old Wilma, exhausted by hunger, has given in to the temptation of stealing Claire’s food through the window while the family was asleep. ‘I am old, was so hungry and I’ve eaten so much dirt in my life’, she explains, weeping.

The community has to decide how to punish old Wilma. The court sits the next day. None of the black inhabitants of Manderlay, of course, has had any experience in meting out justice, but they all instinctively understand what they are taking part in: a solemn, utterly legitimate action, the conclusion of which may be life or death.

Everybody is asked to vote and when the majority agrees that Old Wilma deserves to die, Grace takes it upon herself to execute the verdict. The control of Manderlay is slipping from her grasp and she turns to Mam’s Law in search of answers. Her decision to do so seals the fate of the inhabitants, black and white alike; and Grace’s own fate, too.

Once again it is Wilhelm who sums up the agonizing results of Grace’s idealism and talk of democracy and freedom for the former slaves: ‘America was not ready to welcome us Negroes as equals seventy years ago and it still ain’t and the way things are goin’ it won’t be in a hundred years from now! I fear the humiliations this country has up its sleeve for us free coloured folks will surpass everybody’s imagination. So we voted on it. And we agreed we’d like to take a step backwards at Manderlay and re-impose the old law!’

He tells Grace that the former slaves have voted for her to be their new Mam; they expect her to decline, and when she does they will take the liberty of doing as she did: applying force as a means of persuasion.

When Grace asks: ‘Do you intend to keep me prisoner?’ Wilhelm quietly answers: ‘Only ’til you understand – the way you wanted us to understand. The gates have been repaired and closed. The fences are in good shape but of course they ain’t particularly high, so we’ll probably have to keep an eye on you. (…)

How dumb do you think we really are, Miss Grace? Too dumb to build a ladder if we’d really wanted to get away? For goodness’ sake… did you really believe that even after seventy years we’d not be capable of setting ourselves free? We would if we thought there was any point!’ So in the end, in order to escape, Grace has to make use of the means and tactics she despises the most. And we come full circle.

These production notes provided by IFC Films.

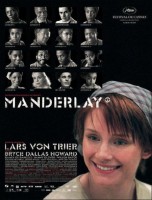

Manderlay

Starring: Bryce Dallas Howard, Lauren Bacall, Willem Dafoe, Danny Glover, Udo Kier, Chloë Sevigny, Stellan Skarsgård

Directed by: Lars von Trier

Screenplay by: Lars von Trier

Release Date: February 3, 2006

MPAA Rating: Not Rated

Studio: IFC Films

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $78,378 (11.6%)

Foreign: $596,540 (88.4%)

Total: $674,918 (Worldwide)