Tagline: Edward Wilson believed in America, and he would sacrifice everything he loved to protect it.

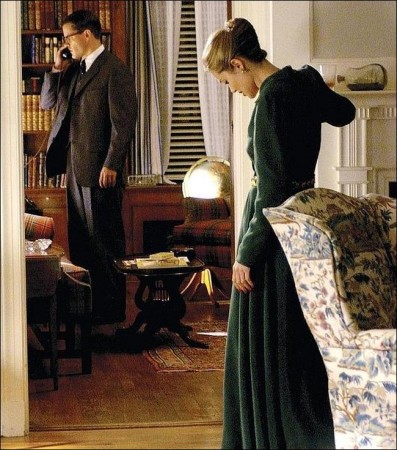

The tumultuous early history of one of the most covert and powerful government agencies in the world is viewed through the prism of one man’s life in the espionage thriller “The Good Shepherd,” starring Matt Damon and Angelina Jolie, directed by Robert De Niro.

James Wilson (Matt Damon) understands the value of secrecy, discretion and commitment to honor, which have been embedded in his soul since childhood, when he was the sole witness to his father’s suicide. As an eager, optimistic student at Yale, he is recruited to join the sacrosanct Skull and Bones fraternity, a brotherhood and breeding ground for future world leaders. Wilson’s acute mind, spotless reputation and sincere belief in the American way of life render him a prime candidate for a career in intelligence, and he is soon recruited to work for the CIA during its WWII infancy.

While working within the very heart of an organization where duplicity is required and nothing is taken at face value, James’ idealism is soon replaced by a growing suspicious nature, reflective of a world settling into the long paranoia of the Cold War.

As his methods are adopted as standard operating procedure, Wilson develops into one of the Agency’s veteran operatives, all the while becoming more firmly entrenched in his mistrust of everyone. His myopic dedication to his work comes at an ever-increasing price and eventually forces him to sacrifice everything in pursuit of his job, costing him his innocence and, finally, his family as well.

Production Information

“The Good Shepherd is a fictionalized version of history which is accurate in almost every incident. But because the filmmakers are liberated from trying to be faithful to the tiny details, they’ve come a lot closer in many ways to capturing some essential truths about this extraordinary period of intelligence, counterintelligence, betrayal and espionage during the Cold War…

There’s no way to understand the present without understanding how we got there. And The Good Shepherd tells us.” —Richard C. A. Holbrooke, United States Ambassador to the United Nations, 1999-2001.

The untold story of the birth of the Central Intelligence Agency—viewed through the life of one man who believed in America and would sacrifice everything he loved to protect his country—is told in The Good Shepherd, an epic drama that features an allstar cast under the direction of Academy Award winner Robert De Niro.

Damon plays Edward Wilson, a patriot who understands the value of secrecy—discretion and a commitment to honor have been embedded in him since his tragic and childhood. As an eager, sensitive student at Yale in 1939, he is recruited to join the secret Skull and Bones society, a tightly knit brotherhood that serves to develop future world leaders. Wilson’s acute mind, spotless reputation and sincere belief in American values render him the prime candidate for an intelligence career by those who monitor the newest recruits.

The idealistic young man is recruited to work for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the CIA, during WWII. It is a decision that will alter the course of his life and change the geopolitical shape of our times as Wilson and his fellow secret group members come to create the most powerful covert agency in the world.

As one of the founders of the CIA, working in the heart of an organization where duplicity is required and nothing is taken at face value, Wilson’s idealism is steadily eroded by his growing suspicious nature, reflective of a world settling into the long paranoia of the Cold War. As his methods are adopted as standard operating procedure, Wilson develops into one of the Agency’s veteran operatives, all the while combatting his KGB counterpart in a global chess match. But Wilson’s steely dedication to his country comes at an ever-escalating price. Not even the growing concern of his wife, Margaret “Clover” (Jolie), and his beloved son (Redmayne) can divert Wilson from a path that will force him to sacrifice everything in dedication to his job.

Nasty Little Secrets: De Niro Uncovers the CIA

Since the early 1990s, actor/director/producer Robert De Niro has been researching the subject of what would become his second directorial effort following 1993’s acclaimed film A Bronx Tale. “Bob has always had an interest in foreign policy and the way that we gather intelligence,” relates Tribeca Films and The Good Shepherd’s producer Jane Rosenthal.

However, the Academy Award-winning actor was not interested in directing the standard fare of a spy-game fantasy. He wanted to make a film that would showcase the actual underpinnings of intelligence services and uncover how these largely anonymous men have controlled our world, at both personal and professional costs.

A friend who was aware of De Niro’s interest in the CIA introduced him to Milt Bearden, a retired 30-year veteran of the CIA who would become the lead technical advisor on the film. The former agent, who ran the CIA’s operations in Afghanistan in the mid-1980s, agreed to take De Niro across Europe and Asia on an educational journey to explore the hidden realms of intelligence gathering.

From the corners of Afghanistan to the northwest frontier of Pakistan—and off into Moscow—De Niro and Bearden traveled extensively to inform the veracity of what De Niro wanted to explore on film. In his travels with Bearden and in their research together, De Niro became privy to information with which few laypersons are entrusted.

“Bob now probably has a better feel for people in the CIA—my generation or the one before—than anybody I’ve seen that was never in the world itself,” notes Bearden.

The author of several books about the CIA, Bearden explains how he is able to share closely guarded details about the United States intelligence operations without sacrifice to the men and women actively serving. “My rule is: ‘Don’t do anything that hurts anybody or puts anybody in danger, and don’t do anything that makes the job harder for anybody who’s still trying to do it,’” he shares.

De Niro’s continued fascination about intelligence gathering would gestate for several years before he was sent a copy of The Good Shepherd—an original script about the early years of the CIA by screenwriter Eric Roth—which dealt with the same issues that were intriguing the director. For the project, De Niro was offered a starring role.

Remembers Rosenthal, “Bob immediately said, ‘Not only do I want to do this, but I want to direct it.’”

The writer, whose resume includes such popular and critically celebrated works as Forrest Gump, The Insider, Ali and Munich, had created a story that wove elements of an exciting spy thriller into the everyday lives of the CIA members who created the agency. “Eric is the best writer working today,” Rosenthal compliments. “It was his look at the internal workings of the CIA that we responded to.”

Roth was interested in an earlier time period than De Niro had been researching with Bearden, but the two quickly found common ground. “I’ve been intrigued by the CIA and how it formed,” says the writer. “This agency was started with literally 17, 18 people, and has ended up with 29,000 today.”

Framing his story with key events in the CIA’s history—beginning the screenplay at the height of the OSS during World War II and closing the timeline with the CIA’s failure to accomplish its crucial mission at the Bay of Pigs in 1961—Roth’s script examined the lives of the men who formed our nation’s modern-day intelligence service.

“I researched people who went into the early years of the CIA and where they came from,” Roth says. “It was traditionally Yale and Skull and Bones.” Almost exclusively, white male Ivy Leaguers of a patrician class—considered the best and the brightest that the U.S. had to offer—ran the government arm.

In fact, this ultra-secret society counts several prominent Americans as members, including President George W. Bush; his father, former President George Bush (who headed the CIA before becoming president himself); his father’s father, Prescott Bush; as well as President Bush’s opponent in the 2004 election, John Kerry. “Some were very brave, idealistic people who decided to use it as a public service,” adds Roth.

Rosenthal and De Niro responded to Roth’s protagonist, Edward Wilson, a sensitive young man who is handpicked to join the OSS in 1939. The producers understood that in telling Wilson’s story, Roth was exploring the very personal side of the agency.

“My character, as a young man, was idealistic. There were very good values that I think he was trying to protect…certain things about America that were wonderful,” reflects Roth. “He has this good-natured, good-hearted quality of justice. I wanted a character who could help write the rules for how they acted at that point, as he is the heart and soul of the agency.

“I was intrigued with what morals people have and what they’re willing to sacrifice,” Roth continues. “As I delved into it, I wanted to know more about what kind of lives these guys lived. What was his family life like, and what was life like with his children? What were his dreams for them?”

A certain amount of paranoia would seem not only justified, but inevitable, for the men who headed counterintelligence, but Roth was curious to know where it ended. “I was also interested in this whole psychological effect of entering a world where you don’t know what is right or wrong—who your friends or your enemies are,” he explains.

Earlier in its history, the United States had had no need for an intelligence organization that mined the depth of foreign information the OSS could provide…until World War II, when our leaders felt it was time for the formation of a covert agency. De Niro offers, “Our country is young at this when compared to Great Britain or other countries that have been doing it a long, long time.”

“We had two huge oceans on either side that nobody could do much about,” explains Bearden. In Europe, on the other hand, intelligence had been a vital tool throughout the years in creating and maintaining intricate alliances with nearby neighbors. With the end of WWII, however, the U.S. had a new dominant position in the world—and with it, new threats.

“The world became polarized,” explains Bearden. “It was the United States and the Soviet Union. You were lined up behind one or the other. And Khrushchev said, ‘We will bury you,’ and so we said, ‘We better figure this out.’ After 1945, that was the beginning of the American empire. An American empire without any intelligence capability didn’t make any sense.”

Roth’s Wilson, a product of these polarizing times, sees himself as both America’s conscience in dealing with the Soviet Union and as America’s protector of freedoms. As head of counterintelligence, his job is to penetrate enemy intelligence and alter our foes’ perceptions. He is also charged with learning the internal workings of KGB and what that agency knows about America.

For the filmmakers, the story became an even more important one to tell as all Americans grappled with decisions our government leaders made before the seminal events of September 11, 2001. “I think it was really in the post-September 11 world that people started to pay attention to this subject,” reflects Rosenthal. “That’s when doors opened, and real discussions began about making this kind of a movie.”

More recently, The Good Shepherd became even more topical to the filmmakers, with daily headlines about columnist Robert D. Novak’s July 2003 outing of Valerie Plame as a CIA operative after an administration source allegedly gave her name. “These are the themes, and this is our subject—this is our national security,” Rosenthal adds. “This couldn’t be any more current.”

In June 2005, Morgan Creek came on board and agreed to produce The Good Shepherd with Tribeca. Morgan Creek’s CEO, James G. Robinson, recognized Rosenthal and De Niro’s passion for the project. He succinctly offers, “This script is as good as it gets.”

Robinson was attracted to the story because he felt that it illustrated the similarities both sides share in the Cold War. “I don’t think that there was much difference between CIA and KGB,” he shares. “The difference is that when the American bureaucracy got out of line, you had remedies to strike back at a system causing harm or discomfort unfairly and illegally. They didn’t, obviously, in Russia.”

It was important to the filmmakers that the events portrayed in the film ring true to not only audiences, but the architects of American intelligence. Richard Holbrooke, former U.S. Ambassador to the U.N., former Assistant Secretary of State and career diplomat, notes of the film: “The Good Shepherd is a fictionalized version of history, which is accurate in almost every incident. But because the filmmakers are liberated from trying to be faithful to the tiny details, they’ve come a lot closer in many ways to capturing some essential truths about this extraordinary period of intelligence, counterintelligence, betrayal and espionage during the Cold War.”

That is the target for which the filmmakers were aiming. “The film is a mixture of real events and takeoffs of characters,” De Niro says. “To be locked into the factual accuracies of those events would be another kind of a movie.”

Damon, Jolie and the Recruits: Casting the Film

The filmmakers knew they needed someone to play Edward Wilson whose performance would encapsulate the agent’s three-decade transformation from wide-eyed schoolboy to grim bureaucrat. Robinson describes Wilson as a man who must pay a high price for devoting his entire life to safeguarding democracy. “He didn’t have a fun life.

He was always doing the right thing,” he feels. According to the producer, the actor who would portray the central character needed to project a “quiet, smart, still-waters-rundeep type of person. That’s who Matt Damon is.”

When approached for the project, Damon’s enthusiasm for the role was profound. “Matt doesn’t make any compromises as far as his character,” commends De Niro. “He’s not, all of a sudden, more sympathetic.”

“He’s one of the finest actors working today,” adds Rosenthal. “He’s willing to take on the challenge and is not afraid to push himself.” Damon’s likability was also crucial for a character whose actions don’t often elicit sympathy from the audience. “Matt is a really nice guy and that comes through, so you have an empathy for this character more than if you had another actor playing this part,” she notes.

Damon was impressed with not only the screenplay; he was eager for the chance to work with De Niro. “It’s a masterful piece of writing, and as an actor, Bob’s the guy everyone worships,” he says. “To have him be there, you feel like you’re in good hands.”

As part of his research, the Harvard-educated actor spent time with CIA veteran Bearden, visited several of the locations in which the story takes place and read multiple books on the CIA. In order to better understand the impact that a career in the CIA would have on one’s home life, Damon also met some of the families of the men who founded the agency.

“It’s hard for relationships to last; it’s a really high-pressure job,” relates Damon. “Edward lives in a world where the stakes are high, and he can’t afford to trust even the people closest to him.”

The main victim of this never-ending secrecy is Wilson’s wife, Clover, his friend’s sister—whom the 22-year-old marries after a passionate encounter at a Skull and Bones retreat, Desert Island, results in her pregnancy.

Academy Award-winning actor Angelina Jolie was cast to play this complicated character. With her exotic looks, the popular star might have initially seemed an unusual choice for the role of a debutante and senator’s daughter. But De Niro had no doubts that she could play an ingénue who would grow to live a life of constant uncertainty as a spy’s wife. “Her instincts were great,” lauds De Niro. “She conveyed the things I thought were essential for Clover in the way she wanted to do it, in the way she was able to do it.”

As a young woman from a wealthy, conservative family, Clover has many personal obligations—from proper deportment to marrying within her social stratum. Jolie found a spark within Clover with which she could identify. “There’s something about her that knows there is something wrong with it all,” reflects the actor. “She is kind of cheeky about it and a bit of a spitfire. She has a wonderful sense of life.”

But a shotgun marriage to a quiet man who does top-secret work proves to be Clover’s undoing. “She is affected by all the negative things about this world,” states Jolie. “She is married to it, and a victim of being around nothing honest, being shut out as a woman…limited as a woman of this time.”

“Angelina has made more out of this than I could ever have imagined,” reflects screenwriter Roth. “I think she’s spectacular.”

Wilson’s work also profoundly influences his and Clover’s son, Edward Jr. Roth’s script had the six-year-old child first meet his father at the end of World War II, when Edward returns from Europe after the completion of his work for the OSS. Played as a child by young actor AUSTIN WILLIAMS, Edward Jr. grows up in awe and fear of his emotionally remote, often physically absent father.

To portray the role of the adult Edward Jr., De Niro and casting directors AMANDA MACKEY and CATHY SANDRICH GELFOND cast young British actor Eddie Redmayne while they were in London to cast two other British roles for the film. De Niro wanted to find an Edward Jr. that could embody a young man who was “fascinated, and at the same time repulsed, by what his father does.”

“Bob originally wanted to cast indigenously,” says Redmayne, who has won awards for his theater work in London’s West End. A stickler for authenticity, De Niro originally considered meeting only American actors for the role of Edward Jr. “Bob’s rigorous, and he worked me hard at it.” However, after several readings with Damon and De Niro in New York, Redmayne proved he was perfect for the role.

Redmayne also had the right look to play Edward and Clover’s son, a man who would follow in his father’s footsteps to get any semblance of attention from the senior Wilson. “He’s got something very classic about him that suits that period very well,” compliments Jolie.

Another player who easily fit into the world of The Good Shepherd was Academy Award winner William Hurt, cast in the role of CIA Director Philip Allen. Born in Washington, D.C., Hurt lived all over the world during his childhood, due to the fact that his father was in the U.S. State Department. Hurt was hopeful that his participation in The Good Shepherd might help him understand another man. “My father came from a very powerful core of moral obligation to the idea of freedom in this country,” he says.

To fill the role of General Bill Sullivan—the U.S. Army official who helped create this country’s first intelligence service and who handpicks Wilson for a career in the CIA—Robinson, Rosenthal and De Niro came across the perfect actor: De Niro himself.

General “Wild Bill” Donovan, the man upon whom the film’s General Sullivan was based, “got young men from Ivy League schools like Yale, who had more of an investment in their heritage and future,” says De Niro. “They would have more to lose if they didn’t win.”

“Some actors have a certain commanding presence, and Bob kept describing who he was looking for. He basically had to look in the mirror to find it,” notes Rosenthal.

While the CIA was run by the U.S. elite, the agency’s staff included individuals from varying backgrounds, such as Wilson’s Italian-American assistant, Ray Brocco. To play the role of Wilson’s loyal right hand, De Niro cast acclaimed actor and graduate of the Yale School of Drama, John Turturro. Turturro had a small role in Raging Bull early in his career, and he has known the actor ever since.

In his research, Turturro came away with a strong sense of how Brocco’s work might affect his home life. “You can’t really talk about your work with your family,” he says. “So you run the risk of disappearing from the lives of those you care about.”

Another blue-collar character in Edward Wilson’s sphere of influence is Sam Murach, the FBI agent who approaches Wilson on the campus of Yale about a job with the government. Predating the CIA, the FBI’s ranks were unlike the privileged makeup of the CIA’s founders. An FBI agent was more likened to a police officer, usually coming from a working-class background.

As with the roles of Clover and Brocco, De Niro knew exactly whom he wanted to play Murach: Alec Baldwin. Baldwin has recently appeared in several acclaimed independent films, garnered an Academy Award nomination for his work in The Cooler and proved his versatility with comic roles on series from Will & Grace to 30 Rock.

While the characters must obviously age over the decades that the story spans, Baldwin’s Murach undergoes a more extreme transformation in appearance than most, something that didn’t bother the theater-trained Baldwin. “He’s been completely willing to jump in and do what he had to do for this role,” says Rosenthal.

Another influential figure Wilson meets during his years at Yale is his English professor, Dr. Fredericks, played by Sir Michael Gambon. For Gambon, best known to American audiences as the wizened Hogwarts headmaster, Dumbledore, in the recent Harry Potter films, the chance to work with De Niro was enough to convince him to take on the role of Fredericks. “To all us boys who are actors, he’s our god,” he laughs. “They should get him to direct every film, then they could get any actor they wanted.”

Although born to privilege, Wilson feels somewhat of an outsider at Yale because of his hidden background. Wilson’s father, played in a cameo role by Academy Award winner Timothy Hutton, made choices that would cast his family under a cloud of suspicion. When Wilson joins the Skull and Bones, he must confess sins of his father to his new family, bonding him for life with them.

To play Wilson’s classmates at Yale, the filmmakers cast a cadre of up-andcoming young actors such as GABRIEL MACHT, who plays Clover’s brother, John Russell. A golden boy with likable charm, Russell befriends Wilson and encourages him to join Skull and Bones. Macht also bears a strong resemblance to Keir Dullea, seminal star of 2001: A Space Odyssey, who plays John’s father, patrician Senator Russell.

Another Bonesman in Wilson’s world is Richard Hayes, a young man who never warms to Wilson and serves as a constant thorn throughout his career. To play Hayes, the filmmakers cast Lee Pace, a Golden Globe nominee for his role in Showtime’s Soldier’s Girl. To explore his role, Pace felt it important to research the Bonesmen who served in the OSS. “These are guys who had a free pass anywhere. They could get into any circle,” he says. “They had a reputation for being wild adventurers who could slum it and get away with that, and also travel with aristocracy in Romania or Berlin or London.”

Called to serve his country with Hayes, Wilson travels to London, leaving his new wife at home to await the birth of their child. Within the OSS, Wilson works with several other recent Yale graduates. “They were 21-25 when they started the OSS,” remarks Pace. “They were kids.”

In the OSS, Wilson learns the fundamentals of intelligence from British spy Arch Cummings, a charming Cambridge-educated young man. For the role of Cummings, the filmmakers initially met with English actors, but ultimately decided to cast an American actor, Tony Award nominee Billy Crudup, who had recently starred on Broadway in The Pillowman and in the thriller Mission: Impossible III.

De Niro and Rosenthal had produced the film Stage Beauty, in which Crudup had starred, so they knew he could well play an Englishman. “Billy came in and did a reading for us that blew us away,” says Rosenthal. “It’s another energy when Arch comes into the scene, and Billy just does that brilliantly.”

“Arch is a British intelligence officer who is assigned to be the primary contact for Edward in London,” says Crudup of his character. “British intelligence was already pretty well established, so my character serves as a mentor.”

As with Turturro, what was particularly interesting to Crudup was how the script told the story of the CIA through personal relationships. “Within this enormous conflict that was World War II, and then the Cold War, people’s relationships became terribly contorted,” he suggests. “And the way that they tried to understand themselves and understand each other and develop relationships became perverted.”

When a Russian defector named Valentin presents himself to Wilson and offers invaluable information about the KGB, Wilson is instantly distrustful. How can he know whether the defector is genuine, or a mole sent by the KGB? Even if Valentin supplies information that is verified, how can Wilson be sure that the Russians are not giving up a few secrets in order to trick the CIA into trusting Valentin? On the other hand, Valentin could be the prize KGB source that makes Wilson’ career.

To play the pivotal role, the filmmakers cast classically trained British actor John Sessions. Sessions has long been popular in the U.K. for his comedic choices, including the original TV series Whose Line Is It Anyway? “I love him in this role, because you’re not sure about him and you want to believe him,” shares Rosenthal.

Wilson is most curious to obtain information from Valentin about Stas Siyanko, or “Ulysses,” Wilson’s counterpart at the KGB. As head of counterintelligence, the CIA agent’s mission is to learn as much as possible about the enemy’s own intelligence officers, how they think and where each one of their vulnerabilities lies. To play the role of Stas, the filmmakers looked to Russia and cast Oleg Stefan, who has starred in over 30 films in the former Soviet Union before his recent immigration to the United States.

“In some ways, they have more of a connection with each other than they do with their governments,” reflects the director. “In their profession, they can identify with each other’s problems because they’re very similar, just on two different sides.”

What would prove most identifiable was the common theme of suspicion that all these men found. Through the fellow spies, lovers and everyone else he meets along his journey, Edward Wilson would all too painfully learn his biggest lesson: Trust no one.

These production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

The Good Shepherd

Starring: Matt Damon, Angelina Jolie, Robert De Niro, John Turturro, William Hurt, Alec Baldwin, Billy Crudup, Michael Gambon

Directed by: Robert De Niro

Screenplay by: Eric Roth

Release: December 22, 2006

MPAA Rating: R for some violence, sexuality and language.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $59,952,835 (60.1%)

Foreign: $39,527,645 (39.7%)

Total: $99,480,480 (Worldwide)