Tagline: What if you could live forever?

What if you could live forever? The Fountain is an odyssey about one man’s eternal struggle to save the woman he loves. His epic journey begins in 16th-century Spain, where conquistador Tomas (Hugh Jackman) commences his search for the Fountain of Youth, the legendary entity believed to grant immortality.

As modern-day scientist Tommy Creo, he desperately struggles to find a cure for the cancer that is killing his beloved wife, Isabel (Rachel Weisz). Traveling through deep space as a 26th-century astronaut, Tom begins to grasp the mysteries that have consumed him for a millennium. The three stories converge into one truth, as the Thomas of all periods — warrior, scientist, and explorer — comes to terms with life, love, death and rebirth.

At once sweeping and intimate, “The Fountain” is a story about love and coping with mortality, which unfolds over three vastly different time periods. Filmmaker Darren Aronofsky got the idea for his screenplay when he realized that, although many cultures have stories about the quest for eternal life, relatively few films have been made about the search for the Fountain of Youth.

“The desire to live forever is deep in our culture. Every day people are looking for ways to extend life or feel younger,” suggests Aronofsky. “Just look at the popularity of shows like ‘Extreme Makeover’ or ‘Nip/Tuck.’ People are praying to be young and often denying that death is a part of life. Hospitals spend huge sums of money trying to keep people alive. But we’ve become so preoccupied with sustaining the physical that we often forget to nurture the spirit. So that’s one of the central themes I wanted to deal with in the film: Does death make us human, and if we could live forever, would we lose our humanity?”

To construct a story that could effectively communicate that theme would require an innovative concept. “What started out as a rough sketch on a restaurant napkin back in 1999 has been through many incarnations,” says the writer / director. “Darren had this idea of a box-within-a-box-within-a-box-structure before we even knew the name of our lead character,” expands producer Eric Watson.

Indeed Aronofsky found himself inspired. “I’d wake up in the middle of the night and look at my stacks of research and think, ‘I have to make this film; it’s in my blood.’” Aronofsky designed a tale that would unfold in three distinct eras. But with so many incarnations of the Fountain of Youth existing throughout history and mythology, he had to consider which one would best represent the film’s ideologies. Co-story collaborator Ari Handel explains, “As we started to conceive the story we researched Mayan culture. We looked at the Bible, too, and found that, in many narratives, the Fountain of Youth is embodied by something living, something organic or nourishing.”

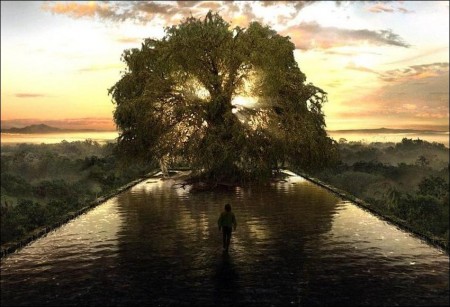

With that in mind, Aronofsky created the film’s Tree of Life, which serves as the Fountain of Youth in the conquistador’s story. In the 26th century, Tom is traveling to Xibalba, a distant nebula, which becomes the film’s futuristic version of the Fountain.

“One of the first things that attracted me to this script was the spirituality of it,” notes producer Iain Smith. “And because that spirituality isn’t specific to any one belief system, it translates into a kind of magic.” As the various mythologies combine, a new myth is created, one that is both otherworldly and familiar by design.

One Man, One Love, One Quest, One Destiny

With a solid thematic guide established, Aronofsky set out to design the motivation of a character who would passionately pursue the Fountain. Thomas Creo, as conquistador, scientist and astronaut has a singular drive and passion. But to tell the story of a man who refuses to accept his fate, or the fate of those he loves, would present a unique challenge.

“It’s difficult to tell a story about the quest for immortality in the present alone. That’s why Thomas’ story takes place in the 16th, 21st and 26th centuries,” says Aronofsky, who goes on to qualify, “but ‘The Fountain’ isn’t a time travel movie in a traditional way. It’s more like three interlocking time periods, where the characters embody three different parts of the same person.”

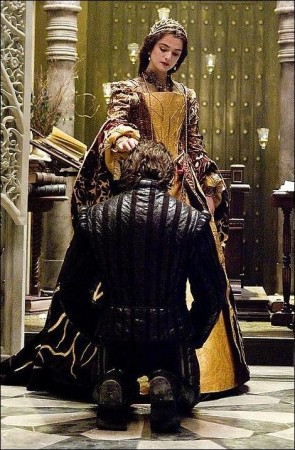

Although the thousand-year span makes Thomas’ tale epic in scope, time is also his greatest enemy. All three of the film’s stories deal with a race against the clock for the sake of love. Tomas the conquistador is charged with finding the Fountain of Youth to protect his Queen from a vengeful enemy who has sworn to destroy her. Tommy the scientist is trying to find the cure for his wife’s cancer before it consumes her. And Tom, who has lived well beyond the normal human life span, is searching for a way to be reunited with his lost love.

“At its core, ‘The Fountain’ is a very simple love story about losing someone and what that teaches you,” offers Aronofsky, noting that, “in every incarnation, Thomas loves Izzi so profoundly that he will do anything to keep her alive. What he doesn’t realize is that by relentlessly pursuing a way for them to be together forever, he’s actually missing out on her life.”

The character of Tomas/Tommy/Tom is complex. He loves without limits; he seeks control where there is none. He needs to learn acceptance. The actor playing him would need incredible range and stamina to give him life. Aronofsky found that actor in Hugh Jackman, who rocketed to fame with his portrayal of the feral, mutant superhero Wolverine in the “X-Men” film series before taking Broadway by storm, playing singersongwriter Peter Allen in “The Boy from Oz.” His performance as “Australia’s favorite son” earned Jackman a Tony Award and further established him as a star of both stage and screen.

“I had a great feeling of hope when I first read the script,” Hugh Jackman says. “The story presents a modern myth. As I understand it, myths are stories told to help us understand the meaning of life. And ultimately those issues aren’t explainable, so we come up with stories that just get into our hearts and make us feel like we understand. These fables may not make scientific sense, but somehow they explain the world to us. That’s what ‘The Fountain’ did for me. It exists in all these fantastic worlds, but Thomas’ struggles are very human.

“In some articulation, Thomas appears in every scene of the film, and in essence, all three roles are the same man. I’d be blessed to play any one of these parts in separate films, so to get to play them all at once was an amazing opportunity I couldn’t pass up. That’s why I slept outside Darren’s door until he gave me the job,” he laughs.

Jackman’s enthusiasm didn’t go unnoticed. “We knew this was going to be a daunting role due to the very difficult physical and emotional transitions’,” recalls Eric Watson. “The actor who took the part had to be ready for that kind of commitment.”

Ironically it was his role as a singing-dancing theater legend—not the roughhewn superhero Wolverine—which convinced Aronofsky that Jackman was right for the part. The director first approached the actor about playing Thomas Creo after seeing him perform live in “The Boy from Oz.”

“Hugh had so much presence and charisma in the show,” says Aronofsky. “He was performing live in front of 3,000 people and yet you felt like you were right next to him. I gave him the script backstage and he called me the next morning and said he wanted to do the film. We were all very passionate about telling this story, so when Hugh connected with it so quickly we knew he was going to be perfect.”

Watson adds, “Hugh was committed to his show for another eight months so we had to wait for him. During that time, Darren and Hugh worked together every week on Hugh’s only day off to evolve the character. So when we got to set, Hugh was Thomas Creo.”

“The character was fantastic,” says the star. “Tomas the conquistador has incredible drive and an unbelievable passion. His devotion to his Queen is single-minded. When she charges him with finding the Fountain of Youth, he’s like an arrow shot from a bow. He’s going to find it. He’s dogged, uncompromising.”

The same can be said about Tommy, the Conquistador’s 21st-century counterpart. “Tommy is a scientist. He looks at death as a disease that can be cured,” Jackman continues.

“His wife, Izzi, is trying to tell Tommy that maybe dying is somehow part of our genetic code, and maybe going through it is part of our growth as spiritual beings. All Tommy knows is that he has a mission: His wife is dying, he loves her and he wants to be with her, so he must eradicate death.”

Jackman believes that same love consumes his 26th-century character, Tom Creo. “Once Izzi is gone, we find Tom floating in space with the Tree of Life. In a way, he’s transferred his love for Izzi to the Tree. She lives there as long as the Tree is alive. He has finally realized he couldn’t save her, but he will save the Tree. Izzi told Tommy the story of Xibalba—that when it explodes the souls living there would be reborn. Tom is hoping that by traveling there with the Tree, he and Izzi will be together again.”

It’s the final testament of a loved one, and Tom puts his faith in it. But even as he travels through space, Tom is trying to cheat death. It’s been nearly a thousand years and he still hasn’t comprehended the lesson his wife is trying to communicate.

“Tommy knows that death is real; he understands that it happens,” says Jackman, “but he wants to know why it has to happen? Hundreds of years ago the average human life expectancy was 40; now it’s 80. So why can’t it become 200, or 400? Why can’t we solve this problem of life ending with death?”

Pursuing the answer to that question ends up leading the character to his greatest regret. “Ultimately, Tom is heartbroken that he wasn’t able to save Izzi, and even more distraught that he didn’t get to spend quality time with her while she was alive. But he’s a doer, a fixer, so he keeps pushing forth.”

Aronofsky agrees, “It takes Tom much longer than Izzi to get there, but eventually he’s going to understand this journey.”

Not only would Jackman have to deal with intricate emotional transitions to play the triple roles, but he would also have to be physically adaptable for each phase of the film. The arc that takes place in Spain is challenging, as Tomas battles his way into a lost Mayan temple to face a soldier with a flaming sword. For the future sequences, Jackman had to be much leaner. He studied tai chi and yoga for 14 months to be ready for the film. The futuristic role would also require the actor to shave his head.

Declares Aronofsky, “Hugh was willing to give us everything we needed to bring Tommy to life, but in order for the story to really succeed, you have to believe that Tommy and Izzi love each other completely.”

“Together We Will Live Forever”

Aronofsky’s search for someone to embody the object of Tom’s unrelenting love ended with Rachel Weisz, an Academy Award winner for her role in 2005’s “The Constant Gardener.” Weisz portrays both Isabel, Queen of Spain, and Tommy Creo’s ailing wife, Izzi, in the present-day story.

“The script was one of the most exhilarating pieces of writing I’ve ever read,” declares the actress. “It was so emotional and thought-provoking—I sobbed like a baby after I finished it.”

Weisz was especially inspired by her character’s journey in the present. “Izzi is a regular person. She’s being confronted by the fact that she is going to die much sooner than she wants, but she ultimately accepts her fate and makes peace with it. I think she’s very brave.”

Aronofsky concurs, “We all wish we could face death the way Izzi faces it. She’s in the prime of her life and she’s going to have to leave everyone she loves behind, yet she manages to do so with grace.”

“If I were in her position, I hope I would have the courage to behave the way Izzi does,” says Weisz. “So many people go out kicking and screaming.”

To create a character with the emotional fortitude to make the transition from life to death, Aronofsky and collaborator Handel talked to nurses who regularly deal with the terminally ill. Handel reveals, “For the most part they suggested that people come to some kind of acceptance of their death, even if it’s just a breath before it happens.”

Aronofsky confirms, “They said that it’s often the families of terminally ill patients who have more difficulty letting go.”

Such is the case with Tommy who would rather run from Izzi’s death than face the reality that she is going to succumb to her disease. Says Weisz, “When Izzi gives Tommy her manuscript and asks him to ‘finish it,’ it’s her way of ultimately saying, ‘Learn to be with yourself. Don’t feel guilty about not being able to save me. Learn to accept your own mortality and you’ll find this peace, too. For the first time, you won’t be afraid.’”

“Izzi wants Tommy to experience her passing with her,” adds Handel. “She wants to share this very significant thing with the person she’s spent her life with. She wants to die with Tommy present, not absent.”

“Right from the start, Izzi is saying to Tommy, ‘Okay, I know I’m going to die and I’m okay with it, but will you just be with me during these moments? Will you look at the stars with me, and read my book and take a walk in the first snow?’” Watson says. “But Tommy can’t do that because he feels like he will be failing Izzi if he accepts her death, so he keeps fighting.”

“For Tommy, this is about hope versus acceptance,” clarifies Jackman. “If someone’s sick, you make them get better. Tommy needs to be optimistic for Izzi; he has to believe he can save her.”

In fact, it may be the only way Tommy can save himself. Weisz sums up the relationship. “Tommy and Izzi have a very strong and very mature relationship. She’s found her understanding and now she’s there patiently, lovingly saying to Tommy, ‘Let it go, live life—live fully and die fully. All the courage you’re putting into fighting death and protecting me, use that courage to face death because that is the greatest liberation.”

Also starring in the film is Oscar, Golden Globe, and Tony Award-winning actress Ellyn Burstyn, who received her sixth Academy Award nomination for her performance in Aronofsky’s “Requiem for a Dream.” In “The Fountain,” she portrays Tommy’s mentor, Dr. Lillian Guzetti, who also shares a special kinship with Weisz’ Izzi. “Ellen told me that I’d better have a part in this film for her, which was fine because I’d written Lilly with her in mind,” says Aronofsky. “She’s a great connector for Tommy and Izzi.”

“Lilly has been a mentor to Tommy and a friend to Izzi,” offers Burstyn. “I think she admires Izzi’s outlook in the face of death and she desperately wants to help Tommy be with his wife in her final moments. She tries to communicate that, but Tommy won’t hear it. And yet, Lilly and Tommy are both scientists, so she can identify with him, too. She knows that asking Tommy to give up on fighting his wife’s disease is like asking him to deny part of himself.”

Burstyn, like her co-stars, was fascinated by the film’s themes. “They’re universal. We certainly do our best to keep death out of our sight, whereas other cultures focus on it. The Buddhists meditate on death. They consciously remember that each moment we live is dead before we even realize it has passed. Trying to hold onto the moment for fear of losing it is to live in a state of death, because the only way to be alive is to live in the present.”

The Tree of Life

To create the three worlds of “The Fountain” would require a group of expert craftsmen. Fortunately for Aronofsky, he assembled a team of artisans years ago at his own Protozoa Pictures. Many of those artists have worked on all of his films.

“Filmmaking is a family affair for us,” says Eric Watson. It is a sentiment echoed by the writer / director who assembled the cast and crew on the first day of principal photography to declare, “Everyone here is a filmmaker.”

“When we did ‘?,’ there were eight people so it was really easy to create that family atmosphere,” muses Watson. “Darren’s mother was there, bringing bagels to the set every morning. Now, suddenly, there are 300 people around but you still have to work to make it an intimate process. If you don’t connect with your crew and your actors, then how are they going to understand what you’re trying to accomplish?”

Aronofsky clearly provides his entire staff of filmmakers with the tools to create a familiar language—an almost “inside” way of communicating. “I’ve never been on a set like this,” says Weisz. “Darren has worked with the same cinematographer and the same production designer on almost all his movies. When you’re on-set with them, you feel completely supported. And you also feel like you’re walking into some hotbed of creativity with all these bright minds around you.”

The director would also take the time to nurture his actors. “He’s definitely an actor’s director,” adds Weisz. “Darren rehearses for weeks before he starts filming and he pushes us on-set. There were days when Hugh and I would be sitting there crying, thinking we’ve just given the best performance we could give, and Darren would say, ‘Okay, let’s do it again, right away.’ So we’d do the scene again, over and over. Darren pushes you to the point where you’re no longer conscious of what you’re doing so you end up with a truly authentic performance. For an actor, that’s just heaven. It’s exactly what you want from your director.”

“I trust him,” attests Jackman. “He’s a general by nature. But he also has this generosity of spirit. He wants everyone to collaborate. He encourages the entire crew to make the film their own. Darren makes it clear that we are all telling this story together.”

“Every department is charged with furthering the thematic intention of the story,” adds Handel. “It doesn’t matter if you are working in costume, lighting, props—it all goes toward telling the best story we can tell.”

Making ‘The Fountain’ wasn’t unlike making three short films, each equally grand in scope. “The first part is very mythical, with the conquistadors in Spain, and this beautiful and mysterious queen. Then the middle story—the one that takes place in present day—is the kind of material the actors could really sink their teeth into, it contains the most emotionally complex scenes to play. And the third part, with Tom sailing through this gorgeous spacescape toward a glittering nebula, is a metaphysical, almost psychedelic journey,” details the director. “It was really fun for us because every few weeks we’d get to sink our teeth into a new millennium with new challenges.”

Describing the environment during filmmaking, Burstyn says, “It was like walking through an eclectic crafts village. There were people making Mayan jewelry and other people building a spaceship. The sets being created were for all three phases of the film, past, present and future. It was just so original. I loved it.”

The story would require great efforts by Aronofsky’s collaborators to create links in all three periods of the film. Working with director of photography Matthew Libatique, production designer James Chinlund, editor Jay Rabinowitz, special effects supervisors Jeremy Dawson and Dan Schrecker, special makeup effects supervisor Adrien Morot, costume designer Renée April, and composer Clint Mansell, Aronofsky carefully crafted the film’s creative and technical elements to help the three stories flow together seamlessly. Director of photography Matthew Libatique has shot all of Aronofsky’s films, going back to A.F.I. Film School. “From the very beginning,” says Libatique. “I knew the story and the scope of the theme would have visual impact.”

That impact required a definitive color scheme. “The first film that Darren and I made together was shot in black and white. On that project we learned that a limited color palette is an effective way of streamlining what you’re trying to say,” notes Libatique. “So this film has a strict palette of white and gold. You do see colors, but they’re earth tones. I shot my own stills to help track the visual language between all three time periods. It was a way for me to see if I was going too far or too close to achieve the density we wanted.”

Production designer James Chinlund designed a wide variety of sets for the film, ranging from Queen Isabel’s magnificent throne room in Seville, filled with colonnades, intricate fretwork, and candlelight; to the Mayan ball court in ancient Mexico; to Tommy Creo’s present day laboratory, where colors and lighting reflect the theme that weaves through the time periods; to the towering Tree of Life, built to represent the immortality that Thomas is searching for; to his spaceship, a unique, organic entity by which Tom floats on his path to discovery.

“The Tree was the greatest challenge the film presented,” says Chinlund. “The eye can detect the slightest variation in the natural structure, so it was critical that we get it right.” The final product was, in Chinlund’s words, “a Frankenstein. We went to a lake in Northern Quebec and found amazing driftwood pieces and brought them back. So the tips of the branches and many of the roots are real. Then the sculpture department pulled molds from those pieces and parts of other trees and we built those around a large steel core frame. Then we added real bark, and fake bark, and paint, and all kinds of things. So it really is a hybrid.”

Chinlund’s tree is being transported by Tom Creo to the distant nebula Xibalba at the edge of the universe, a journey that would force Aronofsky and his team to consider how their spaceship would look. “In typical depictions of a spacecraft, there are a lot of fluorescent panels and gadgets all over,” says the writer/director. “But they get in the way of that amazing view. So we decided to distill the ship down to its most necessary function— which is to carry Tom and the tree through space without losing the spectacle of the journey.”

The result looks more like a soap bubble than the space shuttle. “Five hundred years from now technology is going to be very different, so this spaceship has no buttons or control panels,” notes Watson. “There’s something magical about Tom’s ship because it’s not really explained. You don’t know how he gets the Tree in there, or how he’s controlling his flight. You should just sit back and enjoy the ride.”

In creating the film’s imaginative visuals, the effects team set out to craft a timeless and original look for outer space that did not rely heavily on computer-generated imagery. Aronofsky explains, “Once we settled on a spaceship that was translucent we had to decide how we wanted space to look. I wanted to give the audience something different from what they’ve seen—something organic.”

To achieve that goal, the visual effects team of Jeremy Dawson and Dan Schrecker, from internal-effects house Amoeba Proteus, enlisted English photographer Peter Parks who shoots micro-photographs of tiny chemical reactions interacting in a Petri dish. Dawson remarks, “The textured world of Peter’s photographs was similar to the Hubble photographs we’d been looking at. Once blown up, these living things looked like space to us.”

“What’s really amazing is that the substances that Peter shot are all contained in an area that’s no bigger than a postage stamp,” adds Schrecker. “And none of the elements used to create space are generated strictly from the computer. They’re just collages of actual photography.”

When enhanced these microscopic living things look like a golden nebula. “I liked the idea of something so small representing something so vast,” adds Aronofsky. “It was a great complement to the themes of the story.”

Aronofsky’s ideas about Tom’s ship and the look of space carried through the rest of the production design elements. “There was a definite mandate from Darren about the look of the film,” notes Labatique. “We didn’t want it to have a contemporary gloss, so we decided to try and do as many things in-camera as possible. We do have our share of green screens, but with those screens came elements that we shot ourselves.”

Iain Smith expands on the idea. “Darren believes visual effects are there to support and extend the story but the film should be about the heart.” That is not to say the film doesn’t have its share of eye-popping visual stunts. Special makeup effects supervisor Adrien Morot reveals that it took five long months to rig just one of the effects shots on his to-do list. “There is the scene where Tomas drinks from the Tree of Life. A moment later, he starts to convulse and falls to the ground. Suddenly flowers and greenery start blooming out of his body…from all over. Darren wanted to do that live, without computer effects.”

The shot would inspire Morot to go back to the days when creating a shot using CGI wasn’t a possibility. “Basically we took what is essentially a big plastic bladder and glued leaves and flowers onto the bag. Once it’s inflated, it looks like a full bouquet. We used 60 of them. Hugh even had one in his mouth, with a tube hidden under his beard,” says the supervisor. “Building the air rig was quite a task. It took a lot of power to simultaneously pressurize those things.”

“The beauty of Darren’s philosophy,” says costume designer Renée April, “is that it’s not only about the end product but also about the process of making the film. That’s very unusual in Hollywood. We created everything for the Mayans, from their costumes, to their hairpieces, to the bones they wear.”

April’s pièce de résistance may be Queen Isabel’s gown, a shimmering cascade of olive and gold, with a branchlike pattern woven into the design. For the futuristic sequences, a very narrow color scheme was used consisting of warm gray and charcoal.

“I had to find a line to connect these three stories, not only in color or texture, but also in some little reminder of what was there before,” states the designer. “The Queen’s dress has a pattern with tree branches. Then, in the contemporary story, Izzi has a blanket that you barely see, but it’s got the same design. And of course Tom is traveling with this great tree—so all three periods are linked in an almost subliminal way.”

More overt signals were also employed. “Rachel’s character wears white throughout the film, and she’s almost always backlit by white,” details April. “Hugh’s character is shown a lot in the darkness and shadow, so we dressed him in black.”

Composer Clint Mansell also sought to create connections beyond the visual. “In the beginning, we talked about each time period having its own theme,” notes Mansell, who is another of Aronofsky’s longtime collaborators. “But ultimately Darren does a lot of cross-cutting between the worlds, so I had to focus on the emotional arc of the characters over the film as a whole.” To craft the score, Mansell wrote six themes he called “Lonely Man,” “Snow,” “Tree of Life,” “Red Dress,” “Road to Awe” and “Romance.” “I approached my composition as a three or four-movement symphony that weaves emotions through the story and then climaxes when all the elements of Thomas’ life come together.”

Similarly, James Chinlund’s set designs are meant to further the character’s central motivation and emotional state. “All the sets were designed around the principle of the light at the end of a long tunnel, which mirrors Tom’s voyage on the ship. He starts in the dark and moves toward a distant light, so we created lots of long passages. We used scrims and materials that would diffuse light in different ways.”

Tommy’s laboratory was no different. “The windows in the lab look out onto rock,” continues Chinlund. “The lab is underground, and there’s no light getting in, except in the atriums, where the white light is trying to penetrate. The practicals in the lab had a gold tint—which for us represents logic and science—a misdirect for Tommy on his path toward the white light.”

Aronofsky avers, “Izzi is Tom’s beacon, his only truth—whenever she appears she represents love and purity.”

“Finish It”

In the film, Izzi has written a book about a conquistador on a quest for his Queen, but she tells Tommy to write the last chapter—asking him to “finish it.” Izzi has discovered a sense of peace through her illness, and wants her husband to find that peace as well. She knows it’s the only way for Tommy to complete his journey.

“Taking this journey with Darren as Thomas Creo was a singular experience,” states the film’s leading man. “I think he’s crafted a beautiful story that is at times tragic and enlightening, and sometimes even funny. It’s a love story. It’s visually amazing and intellectually challenging. I hope it touches people. I think it will.”

Adds the writer/director, “I like to be taken somewhere when I go to see films. I like to be transported. I’m hoping that “The Fountain” takes people to places they’ve never seen…but most of all I hope they’re entertained.”

These production notes provided by Warner Bros. Pictures

The Fountain

Starring: Hugh Jackman, Rachel Weisz, Ellen Burstyn, Sean Gullette, Sean Patrick Thomas

Directed by: Darren Aronofsky

Screenplay by: Darren Aronofsky

Release Date: November 22, 2006

Running Time: 97 minutes

MPAA Rating: R for some violence.

Studio: Warner Bros. Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $28,142,535 (51.0%)

Foreign: $27,038,594 (49.0%)

Total: $55,181,129 (Worldwide)