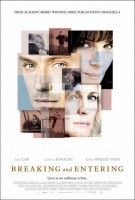

Tagline: Love is no ordinary crime.

A story about theft, both criminal and emotional, “Breaking and Entering” follows a disparate group of long-term Londoners and new arrivals whose lives intersect in the inner-city area of King’s Cross. When a landscape architect’s (Jude Law) state of the art offices in a seedy part of town are repeatedly burgled, his investigations launch him out of the safety of his familiar world.

A story about theft, both criminal and emotional, “Breaking and Entering” follows a disparate group of long-term Londoners and new arrivals whose lives intersect in the inner-city area of King’s Cross. When a landscape architect’s (Jude Law) state of the art offices in a seedy part of town are repeatedly burgled, his investigations launch him out of the safety of his familiar world.

“Breaking and Entering” is Academy Award-winning director Anthony Minghella’s first original screenplay since his 1991 feature debut, “Truly Madly Deeply.” Minghella, Sydney Pollack and Timothy Bricknell are producing for Minghella and Pollack’s Mirage Enterprises.

Breaking and Entering tells the story of a series of criminal and emotional thefts, set against the backdrop of London’s changing culture and geography. Will (Jude Law) and his friend Sandy (Martin Freeman) run a flourishing landscape architecture firm that recently relocated to King’s Cross, the centre of Europe’s most ambitious urban regeneration site.

Their state-of-the-art studio office repeatedly attracts the attention of a local gang of thieves and Will, fed up after another break-in, chases one of the young gang members, Miro (Rafi Gavron), back to the apartment he shares with his mother Amira (Juliette Binoche), a Bosnian refugee. At home, Will lives with his beautiful girlfriend Liv (Robin Wright Penn) who spends most of her time worrying about her troubled 13-year-old daughter Bea (Poppy Roger). Will befriends Amira to further investigate the burglary, but their friendship takes an unexpected turn. Amira soon discovers that Miro robbed Will’s office and becomes suspicious of his true intentions in their relationship. In a state of fear, she sets out to blackmail Will in order to protect her son. With his life already in crisis, Will embarks on a passionate journey into the wilder side of both himself and the city.

Introduction

Filmed on location in London and at Elstree Studios during the summer of 2005, Breaking and entering is Academy Award winning director Anthony Minghella’s first original screenplay to be produced since his 1991 feature debut, ‘Truly Madly Deeply.’ Produced by Minghella, Sydney Pollack and Timothy Bricknell for Mirage Enterprises (Minghella and Pollack’s production company) the film is a co-production between Miramax Films and The Weinstein Company.

Breaking and entering stars Jude Law who previously worked with Anthony Minghella on ‘Cold Mountain’ and ‘The Talented Mr Ripley’ and received Academy Award nominations for both performances; Juliette Binoche who won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her role in Minghella’s ‘The English Patient,’ and American actress Robin Wright Penn who became a household name with her starring role in ‘Forrest Gump’ and was recently seen in ‘A Home at the End of the World.’ The cast includes Vera Farmiga, Ray Winstone, Martin Freeman, Rafi Gavron, Poppy Rogers and Juliet Stevenson.

The behind the scenes team includes production designer Alex McDowell (‘Fight Club,’ ‘Minority Report’) and cinematographer Benoit Delhomme (‘The Scent of Green Papaya, ‘Merchant of Venice,’ ‘Cyclo’). The original score is composed by Gabriel Yared (‘The English Patient,’ ‘The Talented Mr Ripley,’ ‘Cold Mountain’) and Rick Smith and Karl Hyde of the group Underworld.

Who is cleaning my house? Who is cooking my food? Who is washing my car?

For his first original script to be produced since ‘Truly, Madly, Deeply’ in 1991, Anthony Minghella chose a drama, both intimate and wide-ranging, involving the disparate lives of contemporary Londoners. His characters represent a cross-section of residents, from established young professionals to the city’s more recent arrivals: immigrants carrying burdens of war and economic hardship. As the rundown neighbourhoods are redeveloped and the ‘haves’ encroach on the terrain of the ‘have-nots,’ boundaries of class, culture and privilege are blurred and breeched. The players are brought together by a series of actual and metaphorical thefts, which force them to connect, fall apart and come together again in other, better ways.

“A long time ago, I tried to write a play called Breaking and entering,” says Minghella. “The idea was that a couple comes home from a party to discover that their house has been burgled. When they do an inventory of what has been taken, they discover that things have been added and these things indicate problems in their marriage. I liked this idea but I could never write it, although I kept trying.

Then, a couple of years ago, we bought an old chapel in North London to use as our studio. I remember my son Max saying ominously at the time and it’s in the film, ‘Bad place for an office.’ He was at school nearby and knew the area. But I loved the place, loved the location. During the very extensive renovation, I was in Romania scouting for ‘Cold Mountain’ and I’d get these calls from the office saying, ‘Hello, we’ve had a break-in. Hello, we’ve had another break-in.’ I suppose the office had become point for the surrounding estates and it was a fun thing to come in and cause problems.

This sort of ‘baptism of burglary’ reminded me of the idea I’d had 15 years earlier and I started to think there was a different way to say the same thing: that a crime can cause a repair, a break can fix something. In my mind, there’s something in the idea that when damage is done, the repairing of that damage makes everybody stronger. There’s also this idea of the different ways there are to ‘steal’ things from other people; there are all kinds of theft. That’s partly what the film is about.”

Jude Law who plays the pivotal character, Will Francis, says, “It’s a story about the worlds we live in, here in London, that collide and pass by each other, and intertwine. Worlds that we sometimes don’t pay attention to that we take for granted, that we judge or – even worse – which we’re respectful to in a very patronizing way. You think, ‘I donate money to a charity, I give my old clothes to Humana, I’m doing my thing,’ whereas in fact, you’re doing nothing to help anybody who you see as anything beyond a belly. We almost never ask, ‘Who is cleaning my house? Who is cooking my food? Who is washing my car? Are they better educated than me?'”

“It’s not a sellable subject somehow, immigrants,” says Juliette Binoche who plays Amira, the Bosnian refugee mother of Miro, the boy whose breaking and entering sets off a series of unlikely encounters. “We kind of put them in the corner and we don’t want to think or talk too much about them. But I loved that Anthony wanted to address what it is to be an immigrant, how your life can change completely because of a war, because of other people’s decisions. How do you survive as an immigrant if, in your own country, you were a pianist, or a scientist, or a teacher, and then suddenly in another country you become a tailor, a cleaning lady?”

“It’s so easy to judge, isn’t it, when you don’t know people and you don’t know situations?” says Martin Freeman who plays Will’s business partner, Sandy Hoffman. “We all do it. I do it all the time. Sometimes you forget that everyone’s got a story, everyone’s got a life. It’s harder to be black and white once you know the more complicated things at stake in other people’s lives.”

“I wanted to make a film at home in London, and about London,” says Anthony Minghella. “And one of the things I love about London, which all of us who live here celebrate, or most of us do, is the fact that it’s full of people from many nations. It’s culturally so diverse; it really is a melting pot. But I would say that’s the charming analysis. The less charming analysis is that, as the striations of class have altered and blurred, everybody has sort of flocked to the middle-class in an interesting migration that has more or less removed English blue-collar workers. An invisible class has emerged: an underclass, most of who are not English at all but have come from other countries. Although we are extremely brittle and arch about immigration, and often use the issues as a political gesture in elections, we rely on immigrants.”

“My grandmother was a Polish immigrant; she had a Polish accent when she was speaking in French and she was a tailor. So for me, when I read the script, I was taken aback because I didn’t expect it to be so close somehow,” says Binoche. “So far, but so close at the same time. One of the reasons I wanted to do the film is as a dedication to her, my roots. I felt it was a great opportunity to say thank you because it’s still true that there are generations that have to go through a difficult time in order for their descendants to have a better life, better choices. It was wonderful to be able to talk about those people.”

“In London today, we rely on an invisible group of Kosovans, Slovenians, Bosnians, Brazilians, Mexicans, Nigerians, Ghanaians: people who come here and do the jobs that we are loathe to do,” says Minghella. “They’re largely invisible to the welfare state, they’re invisible culturally, but they make up the high percentage of this great city. And I thought, if you make a movie about London, you’d better make a movie which at least looks at that issue, looks at the degree of privilege and the degree of under-privilege that obtain right now in London. I wanted to make a film that somehow glanced at this without making anybody feel that they were just being told off.”

Welcome to London King’s Cross

The changing demography of London is echoed in its changing geography. Significantly, the central character in Breaking and entering is a landscape architect with a comfortable home in leafy North London and a state-of-the-art studio in King’s Cross. The area has previously featured in the classic Ealing comedy “The Lady-killers” and Harry Potter fans know it as the location of the platform from which the Hogwarts Express departs. A vast repository of knowledge and culture, the British Library, is up the road. However, like most neighbourhoods around major train stations throughout the world, King’s Cross has its darker, seedier side.

During the 19th century, King’s Cross was the poorest district in London and it has been a red light district for decades. In recent times, in addition to millions of commuters bound for the Euston, King’s Cross and St Pancras mainline rail and underground stations, the area has been the haunt of transients bent on doing just about anything but catching a train. In the past five years, King’s Cross has also become the location of one of Europe’s largest building sites, the most ambitious urban redevelopment project in Britain since Victorian times.

“The film is set in North London where Anthony, Jude and I live,” says producer Tim Bricknell. “We’ve tried to depict the London of our daily lives which fluctuates between council estates – often very misfortunately designed housing projects that are just hideous to be in and live in – and very plush Victorian and Georgian areas of London. We were extremely fortunate to gain access to the King’s Cross construction site because in many ways, it’s a metaphor for the whole film. It’s about old London changing into new London, an old, stale life transformed by new influences from beyond the British pool.”

King’s Cross is currently in the throes of what Minghella describes as “an architectural convulsion.” In addition to the spectacular feat of engineering culminating in the new London terminus of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL) scheduled to open in 2007, the King’s Cross regeneration project will continue for the next five to seven years. It will ultimately encompass new housing, businesses, offices and roads over an area of nearly 60 acres. Not everyone recognizes the benefits or shares the enthusiasm of government and business for this magnificent example of urban renewal.

“There’s a kind of irony in the way that we live,” says Minghella. “There’s an irony in some guy coming in and buying a smart office and then getting annoyed when people resent it. But of course they resent it if it’s in a place where opportunities are diminished.”

Ray Winstone who plays police detective Bruno Fella is a native of Hackney in the rough-and-tumble East End of London and has direct experience of the displacement of low-income families through ‘regeneration.’ He also recognizes the resentment often engendered by seeming progress. “You’re left with pockets of people that have always lived there and they get the hump because they’re building these beautiful things but it’s not for them,” he says “They get shipped off somewhere and people who can afford to live there move in. I believe that the planners set out with the greatest intentions in the world but there’s never much thought for the people that have a real history of living there. As my character says to Jude’s, ‘There’s the British library over there, there’s King’s Cross, there’s you, and in the middle is crack village. And you wonder why you get broken into.’ No one ever thinks about that when they move into a place. People bring a lot of money into an area where there are other people that have no money and they wonder why their cars get robbed. I’m not saying it’s right, but there’s a reason why.”

“The King’s Cross development is all about the next level of what’s happening in all big cities but, to some extent, that it’s happening in a place like London that has such an incredibly rich history is not all good,” says Production Designer Alex McDowell. “The fact that King’s Cross is being cleaned up and mollified in a spirit of regeneration and improvement is not necessarily any kind of improvement socially and that’s a good part of what the story’s about.”

“London is a complicated city,” says Minghella. “Because I didn’t want to do a pretty London but I wanted to do a London full of colour, saturation, and complexity, I brought Benoit Delhomme on board. He’s brilliant at that. He shot Tran Anh Hung’s ‘Cyclo’ in Vietnam. Saigon is not always pretty, and he managed to give it real depth, and texture.”

Although the production filmed a variety of scenes on the building site at King’s Cross, renewal of the area has advanced so rapidly that another location needed to be found for Will and Sandy’s Green Effect studio. No suitable backdrop of mean streets and derelict buildings can now be found in the immediate area.

Green Effect

“One of the real issues was finding a setting for the Green Effect offices,” says McDowell. “Narratively, it had to be in King’s Cross but there were constraints about it being in a rundown, seedy part of King’s Cross that doesn’t really exist anymore. We’re now five or ten years past that reality. So the challenge was to find a location that could be pinned geographically to King’s Cross yet was far enough away that it was still in the unreconstructed state of an earlier part of London.”

McDowell and locations manager Jonah Coombes followed the thread of London’s little-used, little known canal system on the theory that the waterway would provide a link and a common ‘look’ between King’s Cross and wherever they eventually found an appropriate space. “The screen time was the longest in the Green Effect office but because it had so many specific narrative requirements – it had to be attacked from above, the freerunners had to come through the roof, it had to play for a certain size of architectural practice – we thought we’d be lucky to find even a skeleton of a building.”

After looking at 30 or 40 buildings along the canal heading eastward from King’s Cross, the team came upon their skeleton in the form of an abandoned iron foundry in Bow in London’s East End. The foundry was in such a dilapidated state that it had to be rebuilt from top to bottom, using real construction techniques rather than the cosmetic sleight-of-hand more commonly found on a film set. To the delight of the owner, walls were sandblasted, floors were laid, windows were replaced and steel was used to build interior bridges.

“There wasn’t really any alternative,” says McDowell. “With the restrictions of the budget and the geographical requirements of the location, we had to find a real place and make it our own. In almost every case, that’s what we did – we went into locations and modified them just enough to allow the arc of the story to move smoothly between them but we allowed the location to alter what we did rather than trying to impose our vision on it.”

“I’m so thrilled at what the art department can do,” says Minghella. “Alex would have been a great designer for Kubrick or somebody who would fret over a lampshade. The level of production design expertise in the film world is extraordinary. If directors were half as talented and rigorous as production designers are, there’d be a lot of great films out there.”

In Breaking and entering, Will Francis’s firm, Green Effect, has been hired to plan and design the open public spaces within the new development at King’s Cross. The name of his firm is perhaps misleading. “Will’s a landscape architect but he hates flowers, and he hates plants,” says Jude Law. “He refuses to use grass or greenery. He likes concrete.”

“The manifesto that Anthony wrote for Jude’s character seems so accurate to the notion of what landscape design is: the idea that landscape design is nothing to do with nature, that it’s all about having the same control over the environment that architecture has – it’s a very strong statement,” says Alex McDowell.

Landscape architects are not to be confused with landscape gardeners (in fact, they are rather touchy about the distinction and they don’t consider their profession to be a branch of architecture, either.) Vegetation is, of course, one of the elements of landscape architecture; the others are land, water, buildings, paving, walls, roads and climate all of which are exploited and integrated to reconcile the man-made and the natural environment and make the best use of outdoor space.

Although it is based on amalgam of real elements, the scheme Will’s company proposes for the King’s Cross development is completely fictitious. Both the scheme itself and the scale model of it that dominates the Green Effect office were nevertheless designed for accuracy by McDowell and his team. “Because it’s the centrepiece of the office set and relates to the interplay between Will and Miro, we see enough of the model that it had to be believable to the architectural and landscape design community,” he says.

“We took the framework of the real environment of the King’s Cross project and imagined that Will’s company had been awarded the landscape portion of the scheme. To make that work, we had to take the bones of what’s really there – real King’s Cross, real St Pancras, real rail – but the centrepiece of it is a giant, circular motif redirecting of the canal which is something Anthony came up with. It’s a grand, sort of Venice-like scheme. Architecturally, it’s believable and could work, but I think it would probably flood the whole London rail system if they did it for real…”

“Architecture and the politics of landscape really interest me and always have – what space is, how it is organised, who gets to live in what bit,” says Minghella.

“It’s a strange dynamic wherever you are,” says Vera Farmiga who plays Oana, the Romanian prostitute befriended by Will. “You can go ahead and clean a whole area up, but what happens to the dirt? It’s got to go somewhere, it’s got to go under some carpet, and it’s got to be dusted away to some corner. It just shifts, and then that part becomes derelict.

Breaking and Entering

“The argument is: is it worse to steal someone’s computer or is it worse to steal someone’s heart?” says Jude Law.

When the perpetrators of the actual burglaries at their offices in North London were caught, Anthony Minghella was not surprised to learn that the criminals were young and disadvantaged and that their lives were considerably more complex than his own. Working elements of this real-life experience into a story, Minghella expanded the idea to enhance these mitigating factors: “I liked the idea of a crime in which in some way, the least guilty person was the perpetrator and the most guilty person was the ‘victim’,” he says. “I was interested in the equivocations of crime: why people need to steal, what people are stealing. When we were kids there was a very popular Marxist dictum – I remember placards at university saying, ‘All Property Is Theft.’ There was this notion that owning things is, in itself, wrong. I’ve moved on from that notion but still, I can see that it’s a complex ecology – ownership, theft, property, claiming things, claiming the world, claiming air, claiming space.”

“Sandy’s reaction to the burglaries is quite conservative,” says Martin Freeman. “Or maybe it’s just normal: he’s pissed off that he’s getting robbed, and he wants someone to pay for it. He’s not as overtly forgiving as Jude’s character is but then, Will only get to forgive once and after that, he’s got ulterior motives for forgiving.

I think that Will is more the dreamer, more the poet and Sandy is more the pragmatist, and that comes out in their reactions to things, and their reactions to the extreme of having their space invaded.”

Ray Winstone admits that early on, he had difficulty imagining that a policeman would be as sympathetic and sanguine as his character, Bruno Fella: “It was different from the views that I held about that sort of thing: people break into your house, you naturally want to kill ’em. Then I met a real policeman who was in that situation, who’s been working that area, working with these kids for quite a while, trying to get to them. I guess that educated me, in a way, and I started to understand the script a bit more.

I know what it’s like. I’ve got three daughters and you can talk to them about the reason why they shouldn’t go somewhere, the reason why they shouldn’t do something. They say, “Yeah, Dad, you’re right’ and then they go and do it. Kids take it in and then they just screw it up and throw it away. Human nature, I guess.”

Mothers

“I started to examine the notion of two mothers who had difficult, challenging, and rather wonderful children, and to find a way – with one system nurturing this problem child and another system neglecting the other problem child – of balancing that inside a story,” says Minghella. “And so I created these two families, both of which are foreign families. One has a Swedish mother who’s repaired to London with her child who’s on the autism spectrum and has acute behavioural difficulties. The child is obsessed with gymnastics, only eats food of certain colour, doesn’t sleep and she’s experiencing, during puberty, that particular exacerbation of some behavioural difficulties. Then there’s a boy of a similar age, a bit older, who’s also a gymnast but uses his gymnastic skills to enter buildings in interesting ways. His mother is a Bosnian refugee of similar age – and similarly extraordinary – to the mother of the girl.”

The unlikely meeting between the two families is accomplished by an invasion on both sides: Will Francis, the man in the materially privileged household moves his office into the neighbourhood of the marginal family. Miro, the child of the underprivileged household breaks into that office to steal his computer. Will compounds the problem by ostensibly investigating the burglary but actually ‘stealing’ the heart of the boy’s mother, Amira, and in the process, jeopardizing the fragile balance of his own home life. What he neglects to take into account is the ferocious determination of both mothers to protect their young.

“Will is a man between two mothers in a way – not only between two women but two mothers,” says Juliette Binoche. “At a certain point, when Amira feels betrayed, that’s when the knife comes out for her because, as she says, ‘You must know about mothers, they’ll do anything to protect their children.’ She reaches the point where nothing counts but her son. There are a lot of strong themes in the film but this is one that I particularly love, the relationship between mother and daughter, mother and son, what it is to be a mother, the complexity of it. I think it’s a really touching theme, I suppose because I’m a mother. After a war, men are dead, soldiers are dead. The men go first and what remains are mothers and children. They must try to survive, to fix their lives, to invent another possible life without money – the whole process is so overwhelming when you see it in the news, all the consequences of war. I felt like this theme was talked about in a very subtle way but it’s still there.”

With the break-up of the Soviet Union, of a number of Balkan states were born or recreated, including Bosnia, Croatia, and Macedonia. Changing borders and populations reignited conflict among ethnic and religious groups, in particular, between Serbia (former Yugoslavia) and Bosnia (formerly part of Yugoslavia). The Bosnian capital, Sarajevo, was once considered to be a model of religious and ethnic tolerance but things fell apart in 1991, and in 1992, Bosnia declared its independence from Yugoslavia. As is well documented, the conflict included concentration camps, the mass murder of Muslims in Bosnia by Serb military and police, and the systematic rape of Muslim women. Of the 250,000 casualties, most were civilian. Approximately 800,000 Bosnian refugees fled to other countries.

In order to prepare for her role, Juliette Binoche spent time in Sarajevo, getting a grasp of the language and culture, absorbing the atmosphere of the city and most importantly, meeting with Bosnian women whose experiences during the war would help her to better understand her character. It is a measure of her success that the Bosnians amongst the cast and crew expressed their astonishment at her mastery of the accent and the extras in the scene at the Bosnian Community Centre manifestly accepted her as one of their own.

“We spent a long time looking for first Bosnian and then Eastern European actresses to play the role, but felt in the end that no one could do it better than Juliette,” says producer Tim Bricknell. “She has a history of playing Eastern European women – the world first saw her in “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”; she worked with Kieslowski. However, as we all were, Juliette was very concerned that she wasn’t Bosnian when we cast her. So she worked extremely hard on learning the language and she worked incredibly hard on developing her character. She’s a tremendous actress – possibly the best film actress in the world.”

“Juliette is definitely one of the most inspiring people I’ve ever sat back and watched,” says Jude Law. “She has a sort of liberating freedom and fearlessness, but she’s also grounded in something true, something real and focused. Acting is a kind of sport in that, if you’re playing with someone good, it brings your quality up – they’ll pull you with them. You’re very aware when you’re working with someone like Juliette that they’re really raising your game.”

“Oddly enough, when I’m writing, I don’t really think about actors,” says Anthony Minghella. “The truth is that, in the most banal sense, writing is an investigation of self. When I write Amira the Bosnian refugee, I am Amira – I think of myself. It’s not as mechanical as imagining people; it’s much more peculiar and interesting, and hard to articulate. What I aspire to, as a writer is to go as deeply into my own turmoil and debate and pain, and joy, and try and animate it in some way. When you come out of that and you realise you’ve created these two women who would be interesting, then it becomes quite mechanical because you know that you’re going to have two women at the centre of the film, they need to have quite distinctive appearances so that when you cut quickly you’re going to know it’s the other world, and they will have different characteristics and emotional temperatures. When I was casting Amira and Liv – the complicated, cool, at-odds-with-herself Liv and Amira, this passionate and engaged woman – very few names overlapped. It would have been impossible, I think, for many actresses to play either one or the other.”

“Robin’s one of the few American actresses who’s remained enigmatic, interesting and private, always slightly edgy,” says Jude Law of his other leading lady. “I really think now is her time – she’s very beautiful but there’s always been a lot more to her than that and I think she’s reached an age now where she’s going to be a tear-away and do brilliant work.”

For Robin Wright Penn, the script and in particular, the character of Liv intrigued her because she found it “more nuanced than literal. That gives you something to explore,” she says. “Liv has an inability to connect. She feels guilty about it but she can’t stop questioning, analysing and if you’re living in that zone of always searching you’re not actually living. You’re too busy thinking and planning. It’s all about tactics. You’re always thinking ‘What if we did this? What if we tried that?’ instead of playing ball. She can be with her child because it’s the one place where there’s explanation – she constantly explains to Bea what they’re doing, why they’re doing it. But her relationship, where she needs it most, has none of that communication. She’s isolated and bitter because the other person’s not coming into the bubble that she’s created.”

“Liv and Will have a really good relationship in some ways,” says Law. “They are still very much into each other but they’re in that rut where they can’t talk to each other anymore, and every time they do, they ignite into some kind of attack or defensive move. And it’s not helped by Bea, Liv’s daughter, who’s very needy, won’t sleep, collects things obsessively, won’t eat certain things and, at the age of 12, is like living with a very demanding four year old. That puts huge pressure on Liv and huge pressure on Liv and Will. Will’s actually a very good dad. He’s a stepfather, but he’s a really engaged, loving father and yet he feels that he’s excluded, not quite allowed in the circle even though he’s a part of the family.”

“Robin is probably one of the few actresses who can hold her own as Liv opposite Juliette Binoche as Amira,” says producer Tim Bricknell. “Will Francis is really caught between those two characters. So we needed somebody of similar stature, skill, and beauty as Juliette to play Liv, and Robin amply fulfils that role.”

“Amira is so close to Juliette in terms of a sensibility and spirit that I thought ‘Well I can’t cast her, it would be ridiculous.’ I didn’t tell her about the film and in the end, she called me and said, ‘”Why aren’t you speaking to me about this movie?'” says Minghella. “If you write a Bosnian character, I think your obligation is to find a Bosnian person. I felt it would be wrong to make a film about the diversity of people in London, and then cast a lot of familiar actors in those roles. I told myself I’d have to find a Bosnian woman and cast her, find a Swedish woman and cast her, and enjoy that challenge. I met a huge number of fantastic Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish actresses, and then I met a plethora of Slovenian, Slovakian, Czech, Russian, Bosnian, and Serbian actresses. I met lots of great actresses. In the end, I chose Juliette and I was able to do it without feeling that there may have been somebody else.”

For the character of Liv, Minghella decided to make the Swedish character a Swedish American in order to justify the choice of Robin Wright Penn with whom he had wanted to work since seeing her in Sean Penn’s ‘The Pledge.’ “It was a liberating moment. I suddenly thought ‘Guess what? I wrote it, I can change it!’ he says.

“It was enough for me to be American – we’re such a different breed,” says Robin Wright Penn of her character. “The English are very communicative with what they feel and yet, at the same time, they’re very withdrawn. In a way, the cultural stereotypes reverse and Liv becomes English and cut off while Will becomes the communicator. But they are both guilty of saying the antithesis of what they are doing…”

“Robin is somebody I’ve tried to get in my movies for a decade. She’s a fantastic balance with Juliette – like a ghost, so fragile, and pale, and introspective.

I feel if you asked her to shout she wouldn’t know what that was. She doesn’t need any volume at all. She’s always going backwards and Juliette just comes at you with this life force. They’re a perfect sort of mirror of each other, a yin and yang.”

Will

As with the choice of his leading actresses, Minghella had a similar debate with himself over the casting of Jude Law in the role of Will Francis. The two have been friends for many years and Law’s performances in “The Talented Mr Ripley” and “Cold Mountain” previously earned him numerous accolades, including Academy Award nominations for both films. However, Law recalls that it was not simply a matter of a phone call from the director to advise that he’d be offered the role. “Anthony has a very complicated process,” he says. “He’d just finished his first draft of the script when he called and asked me to read it. We had a really good conversation about it. I read the script, told him I liked it. He said he was delighted and told me, ‘Okay, I’ll get back to you,’ and then he then went away and thought about it for months. I think he was checking in with me because of our past relationship, and because of a mutual respect. But I think he also approaches every project from the point of view of what’s best for the film. So having reached out to me, I think he then had to sit back and make sure that I was right.”

“Anthony hadn’t written the role with Jude in mind but because he’s such a complex actor and has a sort of vulnerability that a lot of male actors don’t want to show – or are unable to show – he’s a very good vehicle for Anthony’s writing which is always delving into the emotional heart of things,” says Tim Bricknell.

“There were a lot of elements to Will that I’d never played in a part before and that were close to experiences I’ve had,” says Law. “I also felt a real sense of how intimate this part was to Anthony and that intrigued me too, if you like, to step into the soul of someone who is very close to the guy who wrote it seemed like an exciting prospect. And there were a lot of ghosts in the script that sort of reflected my life. I felt by going through it, I could maybe banish them.”

“I’ve basically seen Jude grow from this little kid who’s being hardly spoken about to a wonderful talent. There’s no question about that. He’s grown into the actor he is today,” says Ray Winstone. “He’s not just a pretty face, he’s a fine actor and I feel very comfortable being in the same room with a fine actor.”

When it came to casting Will, there are so few people who have the intelligence, and inquiry, and charisma that Jude has,” says Minghella. “I can honestly say, over three movies and a play we’ve done together, there’s never been a second of disconnection between us and he’s never been bad in one second of any of them. He never stops working; he’s always up for another go at something. He’s vulnerable, he’s true. I think that he’s undervalued as an actor – he’s punished sometimes because of the way he looks. Things will get easier for Jude as he gets older and some of the shine comes off. My partner, Sydney Pollack, worked with Robert Redford eight or nine times. I would love to be in that place where Jude was my Redford. He’s as good an actor, as complicated an actor and as special an actor.”

For Law, working with Anthony Minghella has become a matter of absolute trust in what the director will ask of him and what he will do with the end result: “I sort of turn up, literally do what he asks me to do, and go home. I never think to look at a playback or ask to see the rushes – I just give in to him and I leave because I know that he’ll then use the raw material in the way he sees fit for the piece. It’s hugely engaging because on an emotional level and on a cerebral level with Anthony you can’t not be engaged. At the same time, it’s somehow disengaged…I suppose a comparison would be with another film I recently shot where I’d see dailies and rushes because I had no idea what was going to be done with my work so I had to see how I could improve what I was doing. With Anthony, I can just let it go, knowing that he’ll do the best that he can.”

Miro

The perpetrator of the break-ins in the script, and the catalyst for everything that happens thereafter is 15-year-old Miro who lives with his single mother on a council estate and is in thrall to an uncle who masterminds a gang of thieves. “Miro’s not the kind of person who wants to be stealing anything, but he has a very pushy uncle who he can’t really escape from, and his cousin, Zoran, is really his only friend,” says Rafi Gavron who, in his feature debut, plays Amira’s son, Miro. “Zoran’s father runs this ‘business’ where they get tipped off about something being delivered and they steal it. Because of Miro’s amazing agility and his ability to get into small spaces, he does the actual breaking and entering. In a way he likes it because he gets to freerun and he’s out all night doing what he loves. But I don’t really consider him to have a criminal side. It’s just that he gets caught up in this cycle which turns him into a troubled kid.”

“Miro was the hardest character to cast,” says producer Bricknell. “We searched far and wide – in schools, circus schools, drama schools, skate parks, gymnastics clubs, freerunning clubs…Rafi just turned up to one of the open auditions and it transpired that he did a bit of free running – this hobby or sport of leaping, constant movement, and jumping over buildings. Rafi has an incredible confidence and a directness that was astonishing and slightly terrifying the first couple times you met him. Even though he’d never acted before, it felt as if he’d been acting for 50 years and was bored with it already. He’s a 15-year-old boy so that’s quite normal. But as an actor, he’s gone to some tricky emotional places that very few boys his age could go.”

“We spent months and months casting for Miro because we needed a kid who was extraordinary, who could move with real grace and could act, and had the slightly brittle, damaged emotional life,” says Minghella. “Boys hate revealing their inner being. If I had been auditioning at 15, I’d have lasted about eight seconds. I met Rafi ten times, maybe more. And every time we got on badly, and every time I thought ‘It’s him! I know he’s the right person but he’s driving me crazy!’ because he was complicated, and awkward, struggling with himself. The very things, which make him beautiful in the film, were the things that made me not want to cast him because it felt like it was going to be so much work. That sounds ludicrous now because he was such a pleasure, such a wonderful asset to me and to the film.”

When meeting Rafi Gavron for the first time, Juliette Binoche was amused to see a boy who bears such an uncanny physical resemblance to her. “I was really surprised; I thought, ‘Wow! He could be my son.’ And I felt responsible for him, probably as a mother, but also as an actress because it was his first movie and I wanted him to feel comfortable and take risks at the same time. It was a great challenge. Acting is like getting naked a lot of times; it’s like really letting go. Anything that a human being can feel or think or go through – you just have to let it happen inside you – you’re a tool to allow that to happen. So I had to do even more sometimes with Rafi so that he felt it was okay to do it. I think that we had a really wonderful complicity together. I really felt like his mother during the shoot.”

“They’re such nice people and they were very encouraging,” says Rafi Gavron of his director and co-stars. “They made you feel like you’re on the same level when it comes to acting, like you’re an accomplished actor as well which is amazing. Obviously, it’s an unbelievable experience when you think not only are they great actors but they’re kind of well-known celebrities as well. You just think, ‘Wow, this is so weird.’ But the more you work with them, you just feel like it’s one big family.”

In addition to his resemblance to Juliette Binoche and his natural ability as an actor, Rafi Gavron brought natural agility to his role: “There’s one moment in the film where the lads from the carwash are playing football in their little yard in King’s Cross and the ball goes over the fence. When Rafi goes over the fence to get it back it doesn’t look like anything because in movies, we’re used to a movement and then a stunt guy taking over. But Rafi just jumps up onto this fence and is over it, and swinging down a pipe. That’s not bad, you know, for free in this film that you get this kid who has this beautiful dark soul who can also do all the physical stuff. You sort of see who he wants to be when he moves.”

Naturally, although he wanted to and probably could have done all of his own stunts, health and safety issues relating to children prevented Rafi Gavron from doing everything we see in the film. Members of the UK Urban Freeflow ‘parkour’ scene, ‘Kirby’ (for Miro) and ‘Bam’ (for Zoran), were drafted in as freerunning doubles, with ‘E-Z’ acting as freerunning consultant to the production.

Bea / Oana / Sandy

Minghella describes how, after an endless search was required to reveal a Miro in the form of Rafi Gavron, the opposite was true when it came to casting Liv’s daughter, Bea. The director knew he would need to find a winning 13 year-old who could read as Robin Wright Penn’s child and who also had enough natural grace to pass as a budding gymnast. “After labouring in the fields trying to find a Miro, we then started to look at Bea. I don’t know how many thousands of kids the casting department met for the boy’s part before they started searching for a girl. But we had the first casting session and Poppy Rogers came in and I said to the casting director, ‘Let’s cast her, I love her.’ We met a couple of other girls for diligence but I thought ‘this is like a gift, thank you very much. She’s fantastic.’ I think that one of the jobs of directing is just committing. Commit to these people, commit to them being the right people, make them the right people, allow them to be the right people, and just keep committing.”

The talented and popular British actor Martin Freeman was chosen for the role of Will Francis’s friend and partner, Sandy Hoffman. “Martin was another real gift to this film, not least because he’s very different from the kind of actors I normally work with. He’s slightly more acidic. I feel there’s a lot of alkaline in my films and Martin’s got an incredible edge, which I really needed. He resists sentiment so much – he has real cheese radar. Ooh, wait a minute, I’m not doing that…Martin arrived struggling with the material, struggling with me but in a great way. It’s great to work with someone who doesn’t necessarily toe the line but who is always going be fascinating.”

Having cast an actor of Ray Winstone’s stature in a small role, Minghella allowed himself another heavyweight cameo: Juliette Stevenson, star of his ‘Truly, Madly, Deeply,’ in the role of the psychiatrist. “In a way, using one of our most brilliant actresses in this part is an in-joke about ‘Truly, Madly, Deeply’ because what is most remembered of her performance in that film is a scene when she’s at a psychiatrist and she is weeping,” he says. “So in this film, Robin’s character goes to a therapist with Jude’s character and it’s Juliette Stevenson. She wanted to do it and I wanted her to do it because I wanted a hand sort of reaching back into the other movie, to remember this great woman who was in that film.”

For the Romanian prostitute, Oana, Minghella chose Ukrainian-American actress Vera Farmiga whom he’d once seen on a late night rerun of a US television series and made a mental note to find out who she was. Coincidentally, a casting agent suggested Farmiga for the role and gave Minghella a copy of her film, ‘Down to the Bone.’ Having watched it, Minghella says, “I thought, no, this is not the same actress, this is definitely not the same – oh, actually, it is, it is the same actress! And then I met her and the next thing I heard was that, from not having worked for I don’t know how long, Martin Scorsese wanted her to do a film for him as well. We ended up in this ridiculous thing where Martin and I were trying to find a way of making the dates work so that we could both use Vera in a film. That’s somebody who’s on a real upward curve. I think she’s tremendous – she’s got this sort of Meryl Streep thing where you don’t quite know what she really looks like- it’s like she changes shape and height. She’s amazing.”

Farmiga was able to lend a genuine pathos and humour to her character, who represents another real problem in London, that of Eastern European women pressed into prostitution. ‘The sort of sex traffic that goes on here is, again pretty invisible,” says Anthony Minghella. “But I think a lot of girls are brought over here and don’t have a great deal of choice in their profession.”

“I think the tragic thing about Oana is that she’s someone who could be anything,” says Vera Farmiga. “She’s got a great sense of humour, some great insight. She’s quite a philosopher and a realist. It’s the luck of the draw, though, and this is the hand that’s been dealt to her in life. There’s a dark side and there’s a light side, and she’s part of the dark side. She says a bunch of things, and you never quite know what’s true because, basically, as she says, ‘Don’t anticipate anything about me. This is what you hear? This is what you know? Yeah, sure.’ She starts listing all these ailments of her family but which of those is true? In that speech she’s really telling Will and the audience, ‘You think you know my story, but don’t anticipate anything.’ She’s desperate; she’s a wild animal. She’s the fox in your garden.”

“When we first started scouting around King’s Cross, it was like a wasteland: miles and miles of lunar landscape as they try to fix a bit of London – whoever ‘they’ are, and whatever ‘fix’ means,” says Minghella. “As they do this, they scrape away at what is complicated about the city, the complexity of its nightlife. We’re cleaning up London, and in the process, we’re shooing things away, hiding things, pushing problems aside. We’re not solving anything, really. We’re just decorating. I think that the taming of cities, the taming of nature is really interesting because it collides with a suppression of what’s natural within people. In London, right now, the only wild thing that we see is a fox. There are urban foxes everywhere. To me, it’s a reminder that we can’t control everything…”

Green Effect Manifesto

Buildings – architects design them, their thrusting shapes, their visual dramas, their interiors made to human scale, doors with handles we can open, windows we can see through, stairs we can climb…

Between buildings are spaces, female shapes, profound and important, but often neglected. There’s much more of this space than we appreciate, or recognise, even in cities; in the suburbs, in the sprawl around cities, this space dominates, and yet is rarely coherent, rarely planned, rarely understood, is often thought of as negative space, to contrast it with the bulky certainty of function possessed by a building. A building houses us at play, at work, in social gatherings. But outside, in the built environment – for that is what these external spaces are – the built environment glues our living together, and people continue to want to play, work and gather in the open air. A glance at any park on any weekend, the magnet of unroofed spaces, should provide unassailable evidence for the importance of urban landscape. Nevertheless, the built environment continues to comprise miserable passages between buildings, beside roads, throttled and defined by false economies and failures of nerve.

Green Effect is certainly not against nature, although we are accused of being against nature. Rather, we are against the fraudulent advocacy of nature, the misnaming of mediated space as natural, the mistaking of grass as nature, of green as nature. We are against decoration – the flowerbed, the plant, the lawn – those miniature gestures of appeasement which nature would not recognise. Nature is not tame, by definition and there is no space in Britain or Europe that can be described without irony as natural. That a site is designated green space is already a gesture of control. It can be termed a national park or a wildlife sanctuary, its boundaries marked, its animal life monitored – Nature this way!

What Green Effect advocates is hardly modern. Nash was designing both internal and external spaces in the nineteenth century. The Regent’s Canal, Regent Street and Regents Park are all illustrations of a coherent arrangement of private and public environments – elegant terraces grouped around the park, with its inner and outer circles. Regent’s Park is made, of course, a construct no more or less natural than the curving rows of stucco buildings. The confident harmonies, which develop from this marriage of house and environment, have direct and positive impact on those who inhabit them.

It’s great to walk in the park and look at the facades; it’s great to look at the park from inside the buildings. These values are self-evident. The same is true of the Italian Piazza; its grandest expressions – in San Marco in Venice, the Piazza Navona in Rome – without a blade of grass, are as architectural, as pleasing, as defining as any building, as communal as any park. They say something about a culture in the way as our endless verges, our muddy borders, our clumps of bamboos, forlorn trees and concrete flower beds speak volumes about our current society and its lack of respect for what happens to our citizens when they leave their front doors travelling to the glass boxes of their offices. A glance at the budgets for enclosed spaces and exterior spaces indicate society’s true valuation of our constructed environments.

Green Effect views the built landscape as an art, and one which requires as much care as any structure, and as much acknowledgement of design. We believe that there has to be more than a token recognition by architects that they contribute to an environment gestalt; that the choreography of bound and unbound space should be determined as a whole and not simply with the one determining the other, I’m here, fill in around me. Every large scale Urban Project should employ landscape and building architects simultaneously, and Green Effect will only commit to projects where such a dynamic exists and where the possibility lies for the demands of landscape to genuinely effect the position and external characteristics of any structures. Where possible Green Effect will design both. It will favour environment, it will insist that harmonies between the so-called male and female spaces have political impact, not least on crime but most of all, that respect and wit towards exterior space improves the quality of life of every citizen. — Green Effect Partnership 2005

Notes on the Score for Breaking and Entering

It’s always been the case that I find it very difficult to write the screenplay for a film I’m directing until I can hear what the film might sound like. For such a visual medium, the cinema is profoundly located by our ears. I listen and listen to music before I know how to begin. For The English Patient I waded through Arabic and Hungarian songs, until one day, hardly conscious of what was playing, I was sucked into the plangent sounds of a woman lamenting in what seemed to my untrained ear to be Arabic. I went over to my CD player and discovered it was a Hungarian singer, Marta Sebestyen, and the song was in fact from Transylvania.

Marta’s haunting voice, embracing as it did the music of the border between the Middle East and the Balkans, played a significant and narrative part in creating the alchemy of Gabriel Yared’s brilliant score for the movie. The Talented Mr Ripley plunged us into the world of Jazz, and I spent happy months marinating in the American music which had found its way to Europe in the late 50’s, an adventure which led Gabriel and I into a rich and informing collaboration with the virtuoso jazz trumpeter and composer Guy Barker. The music for Ripley became a crucial part of the story, its argument between the improvisations of Bach and his peers and those of the great Jazz players, as defining as Tom Ripley’s own struggle between the formal and the extemporary.

For “Cold Mountain,” a book that Charles Frazier had written to his own private soundtrack of American songs, my musical journey with Gabriel took us to the Appalachian Mountains. We were guided this time by the legendary producer and writer, T Bone Burnett, the musicologist John Cohen and the wonderful collection of Early American Music held by the Smithsonian Institute. For many months we explored mountain folk music, as well as the fascinating devotional music of the region, known as Shape Singing.

After Cold Mountain, I felt it was time to return to a contemporary world, specifically to a story, which came from me and not from a novel. This created more of a challenge musically, because we began without the useful clues and compass of a novel, its concerns, location and period. I had some vague thoughts, but my playlists were particularly eccentric, random, and in this era of the Internet and its musical labyrinths, completely esoteric. I went exploring. I found myself listening to artists and bands I didn’t know, to genres I didn’t understand, but gradually I built up a list of tracks that seemed to belong to the project, or might shape it. My computer keeps a log of what I’ve been listening to, and how many times. It’s a catalogue of my particular obsessions during the period I spent drafting the screenplay. Three of the tracks that featured heavily (by this I mean an embarrassing number of plays) were from Underworld.

Prior to this, I knew Underworld only as the band behind the compulsive and driving dance sound for Trainspotting. I knew ‘Born Slippy’ and its lager-lager anthem and had enjoyed other pieces of theirs when I’d strayed across them in the past. I didn’t know the range and ambition of their music. One of the tracks I became intrigued by, from their 100 Days Off album, was ‘Ess Gee,’ quiet, meditative, addictive and a million miles from stadium music. There’s so much intelligence – musical and conceptual – in Rick Smith and Karl Hyde’s work.

Their music is consistently thoughtful, even in its most undiluted dance form. I didn’t know any of this when I began writing; my ears led me, and I began to write with the sound of Underworld around me, along with two other significant influences on the film, PJ Harvey, and Sigur Ros. If these are unlikely bedfellows, what they share is genuine musicality and intelligence, and an absolutely distinct sound. There is no mistaking a PJ Harvey track, its naked ferocity and honesty, or the childlike foggy landscapes, all distant anthems and toy pianos, of Sigur Ros. With Underworld the signifier is a dense musical landscape, full of ideas, full of sound experiment, and nearly always pulse, long spinning lines of pulse; ideas laid out with no regard to the parameters of a pop song.

A music of questions and responses, corresponding to the nature of its composition, a continuing exchange between Rick and Karl as if they were separate composers in a dialogue with each other. There’s a lot of brain in Underworld and you can recognize it in the music and, crucially, in the production of the music, which is always imaginative, textured, conscious that this is an age in which how a sound is produced is no longer the province of western instruments or, indeed, of musical instruments. They are happy to introduce and play with found sounds, from the street, from the kitchen, from accident. We made contact with them, brokered by their splendid manager Mike Gillespie (who has remained an essential part of the film’s soundtrack) and began the delicate courtship, which led to a marriage between them and Gabriel.

Gabriel Yared is a remarkable composer. Over the past dozen years, he and I have been on many adventures together and Gabriel has created three enduring and beautiful scores for me prior to Breaking and entering. These have earned him enormous recognition, not least from the Academy of Motion Pictures and the British Academy, which have awarded him successive nominations. It’s been one of the greatest pleasures of my working life to participate in his music making and to have learned so much from him. His background – a foot in the Lebanon, a foot in Europe, a broad and intense musical training – means that his music comes from a deep knowledge of the classical repertory, and a wide-ranging love and appreciation of contemporary music from all over the world.

It’s been a feature of the work we’ve done together that Gabriel has always managed to embrace the challenges I’ve set him, the unlikely collaborations, and create scores that are uniquely and recognizably his. None of these projects have been without their difficulties and the fact that Gabriel has persevered with our relationship (and, for that matter, that I have!) is testimony to the deep respect that has grown alongside the work. He is, in my opinion, the finest composer for film working today.

Witnessing Gabriel, Karl and Rick in a room together was a revelation. Musicians instinctively understand each other through playing together, and some early sessions at Abbey Road, of experiment and investigation, led to a growing mutual respect and a great deal of pleasure. A contract of generosity was established. Underworld found a new, if temporary, member. Gabriel discovered two co-composers who offered a thoroughly modern perspective on his process. For all their apparent differences, they were completely relaxed in the studio. Like Underworld, Gabriel enjoys discovering new sound worlds and how they might work inside the strange disciplines of movie soundtracks. For their part, Rick and Karl rightly admired Gabriel’s skills as an arranger, his tremendous gift for a tune and, critically, his experience of how to offer music to film. Music deals with rhythm, silence, and melodies that work like sentences, sometimes like poems.

Film, meanwhile, exists as montage, and is in flux throughout the postproduction process, with its own sentences flexing and changing. And changing. Managing music in that context is a real conundrum. Does the composer wait until the movie is locked, in which case the pressure to compose can result in inorganic, imposed solutions, which haven’t grown with the movie? Does the composer begin making music as early as possible in the process and then continuously update and rethink cues as the picture evolves? Gabriel and I have developed a working method, which veers towards the latter method, organic but requiring great patience. It involves him composing soon after I’ve begun to write, certainly by the time there is a draft screenplay. On “Cold Mountain” he sat across the room from me at my piano while I scribbled at the draft on my desk.

The benefits of this method are apparent; the stamina and goodwill required to tolerate and respond to the constant reworking of the film in postproduction, the stretching and squeezing, the rejection of once perfect cues, is a challenge which Gabriel has almost always met with grace. For Underworld it was a steep, sometimes baffling, sometimes exasperating learning curve. But nonetheless, the composers for Breaking and entering have journeyed on this marathon process with great heart and not a little humour.

For what might be seen as the rawest of the films I’ve made, the most reserved score has been created, supporting the interplay of emotions with subtly smudged themes. A kind of musical impressionism. It’s the opposite of most conventional scoring, where the highs are mascara-ed, the lows swilled with strings. Even what passes for action in the story – burglaries, pursuits – is recognized by inflections of pulse only, as if brass and those ubiquitous movie-music stabs might get the composers arrested for bad taste. The score is properly unlike anything of Gabriel’s I’ve heard, and certainly not what you might expect from Underworld. It really is like the joke we made – music by Undergab, music by YaredWorld.

Rick and Karl introduced us to some wonderfully esoteric instruments like the HANG (a contemporary Swiss percussive instrument, combined steel shells played on the lap, which seems to cross a bell with a tambourine); we encouraged Karl to play his guitar using the EBow, which produces a melancholic sound as if the note were being reversed. Then voices, mostly Karl’s, sometimes ours, emerge and disappear into Rick’s Prospero-like weaving of the sound world. (One feature of Underworld’s approach to music is their generous invitation to those of us who make music to make music with them, and I was thrilled to play and sing a little in the sessions at Abbey Road, making a small mark on the film). The effect of these combinations seems to me, at least, to be perfectly judged for the film. If, as I believe, music in film is another character, this modest and yearning score by three wonderful musicians is a great addition to the cast list of Breaking and entering.

It goes without saying that music for cinema is created by many people, not just the composers. I’d like to take this opportunity to thank everybody for their contribution – from Tim Bricknell, whose calm navigational skills have been essential, to the marvellous Lisa Gunning and Katie Weiland in the editing room (that room of truth), to the raft of talented musicians who played on the sessions at Abbey Road, engineered and mixed by Peter Cobbin. But I hope all of them will forgive me for mentioning three people in particular.

Kirsty Whalley and Allan Jenkins have been involved as programmers and music editors on the last three films, and their patience, musicality diligence and judgment has played an absolutely crucial part, as always, in achieving this score. John Bell, Gabriel’s arranger and friend, died before this work was completed. His gentle soul, his absolute understanding of Gabriel’s music, his quicksilver ability to mend and amend in the studio, mean that we will all, always, think of John, and miss him, whenever or wherever music is recorded.

Anthony Minghella, July 2006

These production notes provided by MGM, The Weinstein Company.

Breaking and Entering

Starring: Jude Law, Juliette Binoche, Robin Wright-Penn, Martin Freeman, Vera Farmiga

Directed by: Anthony Minghella

Screenplay by: Anthony Minghella

Release: December 8th, 2006

Running Time: 119 minutes

MPAA Rating: R for sexuality and language.

Studio: MGM, The Weinstein Company

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $930,469 (10.4%)

Foreign: $8,044,328 (89.6%)

Total: $8,974,797 (Worldwide)