The African adventure is set in Sierra Leone circa 1999, a time when the nation was in the midst of a horrific civil war. DiCaprio plays the role of a smuggler who specializes in the sale of “blood diamonds,” also known as “conflict diamonds” — the precious stones used to finance rebellions, privateers and terrorists. When the smuggler encounters an indigenous Mende farmer whose young son has disappeared into the RUF’s army of child soldiers, the two men’s fates become linked.

Set against the backdrop of the chaos and civil war that enveloped 1990s Sierra Leone, “Blood Diamond” is the story of Danny Archer (Leonardo DiCaprio), an ex-mercenary from Zimbabwe, and Solomon Vandy (Djimon Hounsou), a Mende fisherman. Both men are African, but their histories and their circumstances are as different as any can be until their fates become joined in a common quest to recover a rare pink diamond, the kind of stone that can transform a life…

Solomon, who has been taken from his family and forced to work in the diamond fields, finds the extraordinary gem and hides it at great risk, knowing if he is discovered, he will be killed instantly. But he also knows the diamond could not only provide the means to save his wife and daughters from a life as refugees but also help rescue his son, Dia, from an even worse fate as a child soldier.

Archer, who has made his living trading diamonds for arms, learns of Solomon’s hidden stone while in prison for smuggling. He knows a diamond like this is a once-in-a-lifetime find — valuable enough to be his ticket out of Africa and away from the cycle of violence and corruption in which he has been a willing player.

Enter Maddy Bowen (Jennifer Connelly), an idealistic American journalist who is in Sierra Leone to uncover the truth behind conflict diamonds, exposing the complicity of diamond industry leaders who have chosen profits over principles. Maddy seeks out Archer as a source for her article, but soon finds it is he who needs her even more. With Maddy’s help, Archer and Solomon embark on a dangerous trek through rebel territory. Archer needs Solomon to find and recover the valuable pink diamond, but Solomon seeks something far more precious… his son.

Precious Jewels

“There is no reason why challenging themes and engaging stories have to be mutually exclusive—in fact, each can fuel the other.”

“To me, this movie is about what is valuable,” says director/producer Edward Zwick. “To one person, it might be a stone; to someone else, a story in a magazine; to another, it is a child. The juxtaposition of one man obsessed with finding a valuable diamond with another man risking his life to find his son is the beating heart of this film.”

“These two men set off on a journey, one with the intent of getting off the continent, the other with the intent of getting his family back,” notes Leonardo DiCaprio, who stars as Danny Archer. “But each character ends up struggling with his own moral decisions.”

The world sees diamonds as sparkling, beautiful and highly prized. They are symbols of love and fidelity, affluence and glamour. But in the African country of Sierra Leone, where many of the world’s diamonds are mined, they have taken on a much darker connotation. Zwick explains, “‘Conflict diamonds’ are stones that have been smuggled out of countries at war. They then go to pay for more arms, increasing the death toll and furthering the destruction of the region. They may be a small percentage of the world’s sales, but, nonetheless, in an industry worth billions of dollars, even a small percentage is worth many millions and can buy innumerable small arms. In the late 1990s, people from such NGOs as Global Witness, Partnership Africa-Canada and Amnesty International gave them a name in order to help bring the crisis into the public consciousness: “They called them ‘blood diamonds.’”

Zwick had only a passing knowledge of the term and its meaning when producer Paula Weinstein first sent him the script. “I had heard the phrase, but I didn’t fully understand its implications,” he offers. “The more I learned, the more fascinated and horrified I became, and the more I realized this was a story that needed to be told.”

Weinstein developed the screenplay with screenwriter Charles Leavitt and executive producer Len Amato. Producer Gillian Gorfil had initiated the project with C. Gaby Mitchell, who shares story credit with Leavitt. When they came on board the project, Zwick and producer Marshall Herskovitz continued to develop the story with Weinstein.

Weinstein recalls, “I had made an anti-apartheid movie called ‘A Dry White Season’ many years ago and spent some time in South Africa. I knew about conflict diamonds, so the idea of making a film that showed their effect on the people of Africa was very significant to me.

“First of all,” she continues, “we had great writers, and then the moment we got the script, I wanted to go to Ed Zwick. Ed and his partner, Marshall Herskovitz, have demonstrated a sensibility that I share; they are interested in stories about the real world, and they are committed to telling them truthfully. I knew they would not only embrace the material but be fearless in telling the whole story. A project like this needed someone with a creative backbone in order to get it made, and made right.”

Herskovitz has had an association with Zwick dating back almost 30 years. He acknowledges that the subject matter of “Blood Diamond” posed a challenge to the filmmakers in balancing images that have the potential to, at once, confront and entertain an audience but adds that there is ample precedence for walking that tightrope. “It was hard for us to look at some of the material about Sierra Leone and the truly horrendous circumstances there and imagine them in a Hollywood film, but history has repeatedly shown us you can do films that deal with difficult subject matters for a wide audience when there is an important story to be told.”

Zwick agrees. “I don’t think movies can ever be too intense, but people have to understand why you’re showing them the things you are showing them. In the case of ‘Blood Diamond,’ there are brutal truths, but there is also great beauty and emotion to be found in the lives of those caught up in those situations.”

“What really impressed me about Ed,” Leonardo DiCaprio remarks, “was that he wanted to make an entertaining adventure film, but mixed in were some complex, highly charged political statements. That’s what really got me excited about this film.”

“It has been my belief that political awareness can be raised as much by entertainment as by rhetoric,” asserts Zwick. “There is no reason why challenging themes and engaging stories have to be mutually exclusive—in fact, each can fuel the other. As a filmmaker, I want to entertain people first and foremost. If out of that comes a greater awareness and understanding of a time or a circumstance, then the hope is that change can happen. Obviously, a single piece of work can’t change the world, but what you try to do is add your voice to the chorus.”

Working on the script, the filmmakers found that they themselves gained a better awareness of the issues at hand. Zwick notes, “It seems that almost every time a valuable natural resource is discovered in the world—whether it be diamonds, rubber, gold, oil, whatever—often what results is a tragedy for the country in which they are found. Making matters worse, the resulting riches from these resources rarely benefit the people of the country from which they come.”

Producer Gillian Gorfil, a native of South Africa herself, stresses that, while shedding light on the issue of blood diamonds, this movie is not intended to cast a shadow over the entire diamond industry. “It is important to me that this film is not anti-diamond. The issue is blood diamonds, which have very specific origins.”

Zwick also emphasizes that the story of “Blood Diamond” is not exclusive to one corner of the globe. “There is something universal in the theme of a man trying to save his family in the midst of the most terrible circumstances. It is not limited to Sierra Leone. This story could apply to any number of places where ordinary people have been caught up in political events beyond their control. There are just so many innocent victims.”

As the filmmakers delved into the tragedy of blood diamonds, a more farreaching crisis began to resonate with them. “It’s a remarkable thing when a movie tells you what it wants to be,” Zwick muses. “While working on this film, the haunting theme of the child soldiers and the debasement of children took on greater import. The exploitation of resources in the third world has inevitably been linked with the exploitation of children. There was a phrase I wrote on the outside cover of my script. It was the first thing I saw at the beginning of every shooting day. It read: ‘The child is the jewel.’”

Eyewitness

“Sorious was a godsend… He was a friend,a consultant, an authority. He was the soul of the production.”

A self-described “perpetual student,” Zwick immersed himself in learning all he could about the history and repercussions of conflict diamonds, child soldiers and the revolution in Sierra Leone before exposing a single frame of film. An internet search led to a connection with another filmmaker who would prove invaluable to every facet of “Blood Diamond”: award-winning documentarian Sorious Samura.

“I went online to look up a documentary I had heard about called ‘Cry Freetown,’” Zwick recalls. “I put in a credit card order for it, and a week later a letter arrived saying, ‘We couldn’t help but recognize the name on your card and wondered if you were thinking of doing something about Sierra Leone. If so, please feel free to call me.’ I couldn’t believe my good fortune. Sorious Samura’s documentary about Sierra Leone is the single most authoritative record of what happened there during the civil war. While many journalists were fleeing the country and much of the world chose to ignore what was happening, here was someone who stayed and actually filmed it.”

Samura reveals that his decision to film the atrocities unfolding around him in 1999 was less an artistic decision than “a desperate cry in the dark for us to be saved. I had seen the difference the media made in covering the war in Kosovo, so I decided to take a camera and film what was happening in Sierra Leone. It was very dangerous—they had already killed about nine local journalists—but I thought if I could survive, then the world would see; if I could give the international community a wake-up call, maybe they would take action.”

The result was “Cry Freetown,” which brought Samura worldwide recognition and several prestigious awards, but he could not imagine that, years later, it would bring him to the set of a major motion picture. He relates, “When I learned that Ed Zwick was working on a feature film about Sierra Leone, I wanted to make sure he got the details right. Even though it was going to be a drama with fictional characters, it was important to convey a sense of what really went wrong—when it happened, how it happened, and why. When I talked to Ed, I could see he was as committed to getting it right as I was. I gained great respect for him, and told him I wanted to be a part of the film.”

“Sorious was a godsend. He made himself available to me, and I took full advantage of that,” Zwick says appreciatively. “You cannot put a value on having someone who was actually there. He became much more than a technical advisor. He didn’t just advise us on practical things like wardrobe and props. He led us to people who understood the Mende language, Krio dialect, and so many nuances of Sierra Leonean culture. He had spent time with child soldiers, smugglers and mercenaries. He was indispensable to the actors, especially Leo and Djimon. He was a friend, a consultant, an authority. He was the soul of the production.”

Production notes provided by Warner Bros. Pictures

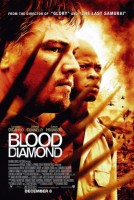

Blood Diamond

Starring: Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Connelly, Djimon Hounsou, Michael Sheen, Stephen Collins

Directed by: Edward Zwick

Screenplay by: Edward Zwick, Marshall Herskovitz

Release: December 15, 2006

MPAA Rating: R for strong violence and language.

Studio: Warner Bros. Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $57,377,916 (33.5%)

Foreign: $114,029,263 (66.5%)

Total: $171,407,179 (Worldwide)