Tagline: Something wicked this way hops.

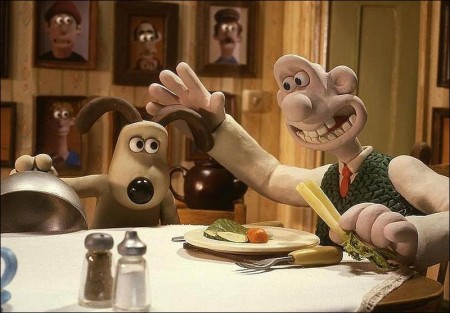

The cheese-loving Wallace (Peter Sallis) and his ever faithful dog Gromit-the much-loved duo from Aardman’s Oscar-winning clay-animated “Wallace & Gromit” shorts-star in an all new comedy adventure, marking their first full-length feature film.

As the annual Giant Vegetable Competition approaches, it’s “veggie-mania” in Wallace & Gromit’s neighbourhood. The two enterprising chums have been cashing in with their pest-control outfit, “Anti-Pesto,” which humanely dispatches the rabbits that try to invade the town’s sacred gardens. Suddenly, a huge, mysterious, veg-ravaging beast begins terrorizing the neighbourhood, attacking the town’s prized plots at night and destroying everything in its path. Desperate to protect the competition, its hostess, Lady Tottington (Helena Bonham Carter), commissions Anti-Pesto to catch the creature and save the day.

Lying in wait, however, is Lady Tottington’s snobby suitor, Victor Quartermaine (Ralph Fiennes), who’d rather shoot the beast and secure the position of local hero-not to mention Lady Tottington’s hand in marriage. With the fate of the competition in the balance, Lady Tottington is eventually forced to allow Victor to hunt down the vegetable-chomping marauder. Little does she know that Victor’s real intent could have dire consequences for her…and our two heroes.

Just over 16 years ago, movie audiences were introduced to an eccentric, cheese-loving inventor named Wallace and his loyal canine companion, Gromit, in a clay-animated short titled “A Grand Day Out.” The short film comedy-which takes Wallace and Gromit to the moon and back in the quest for an unlimited supply of cheese-was the brainchild of a young stop-motion animator named Nick Park.

The Long and Short of It

Six years in the making, “A Grand Day Out” had started as Park’s graduate project when he was a student at the National Film and Television School in Beaconsfield, England. Midway in the production, he connected with Peter Lord and David Sproxton, who had already made a name for themselves in the field of stop-motion animation, under the Aardman Animations banner. Impressed with the work Park was doing, Lord and Sproxton invited him to bring his film to Aardman, where they could collaborate on multiple projects.

In 1990, “A Grand Day Out” was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Animated Short, competing with another Park creation, “Creature Comforts.” The latter took the Oscar that year, but Wallace & Gromit would soon get their due. In 1994, Park’s second Wallace & Gromit film, “The Wrong Trousers,” won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short. Two years later, the Wallace & Gromit short “A Close Shave” brought Park back to the Oscar podium to accept his third Academy Award in the same category.

With each new adventure, Wallace & Gromit built on their devoted fan following, which began in England and gradually spread around the globe. Now, for the first time ever, the inventive entrepreneur and his faithful, four-legged friend are headlining their first feature-length movie, “Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit.”

“It’s really a dream come true,” director, writer, producer Nick Park states. “Wallace & Gromit were my college creations, and it is quite something to think that they are starring in their first full-length feature film.”

“Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit” marks the second collaboration between DreamWorks Animation and Aardman. The two companies had previously teamed on Aardman’s first feature-length film, “Chicken Run,” which was an unqualified success. An unabashed fan of Aardman’s work, DreamWorks Animation CEO Jeffrey Katzenberg notes, “I saw my first Wallace & Gromit short about 15 years ago and, like everyone else in the world, I was captivated by the characters. There is something wonderfully absurd and appealing about them. I think the charm of Wallace & Gromit comes from Aardman’s unique style of animation. It’s such a visual medium-it doesn’t matter what language it’s translated into; it’s funny and delightful and witty.”

Producer Claire Jennings observes, “It seems, over a long period of time now, wherever Wallace & Gromit have gone, people have taken them into their hearts. People around the world love them. It will be interesting to see how a new generation takes to Wallace & Gromit.”

Producers David Sproxton and Peter Lord acknowledge that having a known commodity actually added to the pressure of expanding Wallace & Gromit’s world. “In a way, `Chicken Run’ was easier because it had entirely new characters,” says Sproxton. “Nobody knew anything about them, so we were free to show them in whatever light we saw them.”

Lord continues, “So many people know and love Wallace & Gromit…and, of course, there are also people out there in the world who have never seen them before. We knew we needed to tell a story for those people as well as for our loyal fans.”

To stay true to the history and traditions of Wallace & Gromit, Park, Lord and Sproxton assembled a creative team that has spent many hours in and around the animated duo’s 62 West Wallaby Street address. Helping to lead that team was Park’s fellow director, Steve Box, who had served as an animator on both “The Wrong Trousers” and “A Close Shave.” “Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit” marks Box’s feature film directorial debut.

“Making a 30-minute Wallace & Gromit movie is time-consuming and requires a lot of patience and care. Making an 85-minute feature is like making the Great Wall of China with matchsticks,” Box laughs. “It’s a monumental feat, actually. It was five years of solid work, because every tiny, little thing matters so much. But I think the biggest challenge of taking these characters from 30 minutes to 85 minutes was finding the story.”

Mark Burton, who had worked on “Chicken Run” and more recently co-wrote “Madagascar,” and Bob Baker, a co-writer on both “The Wrong Trousers” and “A Close Shave,” collaborated with Park and Box to craft the story and screenplay for the movie.

“It took a while to come up with an idea we felt was expansive enough to suggest a full-length movie,” Park recalls. “Steve and I sat for hours on end with the other writers, and we suddenly hit on this idea about a Were-Rabbit. You know, the Wallace & Gromit movies have always referenced other film genres, and we thought a great genre to borrow from would be the classic Universal horror movies. But, in our movie, instead of a werewolf, we have a Were-Rabbit…and instead of devouring flesh and blood-in Wallace & Gromit’s world, it’s got to be something more absurd-we made it vegetables. It’s a vegetable-eating monster so, in effect, “The Curse of the Were-Rabbit” became the world’s first vegetarian horror movie.”

Say Cheese

Without question, the least challenging aspect of the making of “Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit” was the casting of the title roles: Gromit, for the obvious reason that he never speaks; and Wallace because that casting decision had been made more than 20 years ago. Peter Sallis has been the voice of Wallace since the character’s inception so, for the feature film, Lord states, “There was never any discussion about it. It had to be Peter.”

Park affirms, “I couldn’t imagine Wallace without Peter now. Peter is Wallace and vice versa. Back when I was in college creating these characters, Peter seemed like a natural for Wallace. I knew him from his series, `Last of the Summer Wine,’ and his voice just stood out to me. I was a shy student with not a lot of money to make the film, but I wrote to him and he very happily obliged me.”

Sallis relates, “Nick Park liked the sound of my character on `Last of the Summer Wine,’ and that was really what started it all. I went to the Beaconsfield Film School, where Nick was a student-this was back in 1983-and we literally sat side-by-side and recorded `A Grand Day Out’ with a microphone on the desk in front of us, no fancy glass booth or anything like that. I would say the lines and Nick would interrupt and say things like, `I think it would be better this way…’ At first, I’ll admit, I was just a little bit skeptical. I thought, `This guy is a student here, and I’ve been in the theatre for, how many years?’ But it dawned on me, after a very short time, that he was absolutely right…and he’s been absolutely right ever since.

“Of course, in 1983, I hadn’t any idea what would become of it,” Sallis continues. “For one thing, Nick couldn’t even show me the character models; all he had was a storyboard. But six years later the phone rang and it was Nick saying, `I’ve finished it.’ I thought, `Oh, it’s only taken him six years, goodness me.’”

Park offers that Sallis’ vocal performance contributed to more than just how the character of Wallace sounds. “Wallace had a very different looking face, at first. It was really the way Peter formed his vowels and said words like `cheese and crackers’ that suddenly made me picture him differently. I let Peter’s voice dictate to me how Wallace looked, and it evolved from there.”

Now, all these years later, Park says, “Peter sounds as young and as bright as ever. He brings so much energy to the part, and we just enjoy working together so much; he just makes us laugh all the time.”

Through all of his adventures, Wallace has had a silent partner at his side: his dog, Gromit. Sallis says, “Wallace & Gromit live and work together and they are quite chummy. People who are familiar with the characters will tell you that Gromit is the brains of the outfit, but,” he counters, “that does not alter the fact that Wallace is a rather clever inventor. I mean, he got them to the moon and back much quicker than the Americans did,” Sallis smiles, referring to the duo’s first adventure in “A Grand Day Out.” “You have a man who, on one level, is so brilliant that he can put his hand to making almost anything, but, on another level, is really a bit `thick.’ And then you have a non-speaking character with the most expressive eyes and ears that have ever been created. Together, they have great chemistry, which is entirely due to Nick Park.”

“Obviously Gromit can’t say anything, but that’s an important part of Wallace & Gromit’s relationship,” Park notes. “They don’t have to talk; they have a bond that goes much deeper. Wallace is the daffy inventor who acts first and thinks later. Gromit is the opposite; he is very cautious. Wallace is a doer, but Gromit is a thinker; he is definitely more intelligent-the long-suffering partner who has to get Wallace out of his own self-made scrapes. So much of the comedy relies on Gromit’s reactions to Wallace.”

Although Gromit doesn’t talk, Steve Box agrees that his expressions speak volumes. “I think Gromit is the character the animators most fear because his expressions are so important. In fact, when we wrote the script, we wrote actual dialogue for Gromit-`What the heck was that?’ or `If only I could keep him under control’-so his performance is crucial to the film. And because he needs no words, he can communicate in any language.”

In “The Curse of the Were-Rabbit,” Wallace’s latest inventions are being put to good use. The townspeople have been anxiously awaiting the Giant Vegetable Competition, where they can finally parade their prized produce. Meanwhile, the town’s prolific rabbit population is threatening to turn the sacred vegetable gardens into an all-you-can-eat buffet. Riding to the rescue is Anti-Pesto, Wallace & Gromit’s humane pest control company, which promises total plot protection, complete with an “eye-popping” early warning system.

Things really start hopping when the competition’s official hostess, Lady Tottington, employs the services of Anti-Pesto. Lady Tottington is voiced by Helena Bonham Carter, who says, “Lady Campanula Tottington is an upper-class lady, although she is somewhat batty…a bit eccentric perhaps. Her passion is growing vegetables; however, she has a bunny problem-her lawn is infested with hungry rabbits-so she phones up Wallace & Gromit, who run a humane pest control company-humane being most important to her. I think she’s lovely. She doesn’t look anything like me-unless I have really bad self-perception,” Bonham Carter laughs, “but she has a very sympathetic heart and I love her.”

Bonham Carter is not the only one who loves Lady Tottington. Peter Sallis notes that Wallace immediately has eyes for her. “Wallace can’t believe that he’s actually going to meet her, and when he does, he can hardly speak. And so, she becomes the centerpiece of the whole event, as far as Wallace is concerned. He is determined to rescue her by ridding her beloved vegetable garden of all those pesky pests.”

Wallace’s infatuation with Lady Tottington draws the ire of her pompous suitor, Victor Quartermaine. Victor has been courting the wealthy lady of Tottington Manor and begins to see Wallace as a possible threat to his fiancée or, more truthfully, his finances. Ralph Fiennes, who gives voice to Victor, observes, “I suppose you could say he is posh, but he is more what we would call a cad. He’s outrageous; he thinks he is the most important person in the world, not to mention the most attractive and the bravest, but I think he is a bully. He despises Wallace-to him Wallace is a non-entity, just a little man getting in his way with Lady Tottington. Victor is trying to woo Lady Tottington by helping her dispose of her rabbit problem. The trouble is Victor wants to shoot the rabbits-blast them with his shotgun-but Lady Tottington loves the rabbits and doesn’t believe Victor’s methods are appropriate. She hires Wallace and Gromit’s company, Anti-Pesto, to humanely solve the rabbit problem, which infuriates Victor.”

Directors Nick Park and Steve Box were thrilled with the casting of Fiennes and Bonham Carter, and say that the two Oscar nominees, who are better known for their more dramatic roles, had tremendous fun with the broad comedy of “Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit.” “Helena had so much energy and brought such a bubbly eccentricity to her character,” Box comments. “I also loved Ralph’s characterization of Victor, which I think is absolutely hilarious.”

Park recalls, “We showed the model of Lady Tottington to Helena, and she was immediately inspired and starting talking in a rather posh, yet goofy way. She is a great classical actress, so I was in complete admiration of the way she was able to have fun with the character. Like Helena, Ralph was so willing to have fun with the part and play Victor in such an arch way. I just loved the quality of his voice and what he brought to the part.”

Hailing from England, Fiennes and Bonham Carter had been longtime fans of Aardman and Wallace & Gromit, so both actors jumped at the chance to be a part of their world. “There was never any question of whether or not I wanted to do the movie,” Bonham Carter states. “I love everything Aardman does. Their films have such great heart and such a keen observance of human nature. They are very good at picking up on those little idiosyncrasies that make people tick, and with Wallace & Gromit, they hit upon two adorable characters who are a terrific double act. They are like a great comedy team who have a different way of communicating.”

Fiennes notes, “One of the reasons I wanted to do this film was I particularly like this form of animation. Clay animation doesn’t have the graphic slickness of other kinds of animation; the very fact that the animators have to animate each figure gives it a hands-on quality. There is something about it that is akin to a child playing with toys…a feeling that you could possibly reach out and play with these characters. Then there is the sheer imagination and inventiveness of the Wallace & Gromit films. I was a huge admirer of the films even before this. I find the sublime silliness of the comedy to be very funny.”

Also lending their voices to the main cast of “Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit” are Britain’s award-winning comedy favorite Peter Kay, playing the town’s skeptical policeman, PC Mac; veteran actor Nicholas Smith as the town’s Vicar, Reverend Hedges, who is terrorized by the Were-Rabbit; and veteran actress Liz Smith as Mrs. Mulch, who will do whatever it takes to protect her treasured harvest.

Model Performances

In any animated film, the characters’ performances belong as much-or more-to the animators as to the actors providing the voices. That is especially true in the world of stop-motion animation, where the animators spend countless hours bringing inanimate puppets to life, bit by infinitesimal bit.

The process begins with the design of the puppets themselves. In their short films, Wallace & Gromit rarely encountered other human characters, but that was not to be the case in their first feature film. Model production designer Jan Sanger and her team were charged with the design and creation of an entire neighbourhood of both people and animals of assorted ages, shapes and sizes. In addition, because the characters’ hair and clothing are molded and hand painted on each individual puppet, the modelmakers also had to serve as a de facto costume designers and hairstylists-albeit for clients with decidedly eccentric tastes.

Park offers, “The central characters of Wallace & Gromit were already established, but there were many more townspeople involved in the story. We had a great team building the models for about 40 additional characters in the film, including Victor and Lady Tottington. It was a lot of work designing those two characters, especially Lady Tottington, who needed an entire wardrobe of dresses. There were some pretty heated debates about which dress she would wear in what scene,” he admits laughing.

Sanger says, “It was very interesting having Lady Tottington and Victor come on the scene, because they are flamboyant and it allowed us to introduce another dimension to Wallace & Gromit’s world. They were fantastic characters to work with. Victor is quite pompous and has his own agenda for what to do with the rabbits. We generally had him in his safari hunting outfit, which leaves no doubts about his intentions. And Lady Tottington: with her grace and elegance, we spent a lot of time looking through fashion magazines to create a wonderful costume range for her.”

Sanger reveals that Wallace’s flirtation with the posh Lady Tottington even had an influence on his all-too-familiar wardrobe. “Wallace sets out to charm Lady Tottington, so we managed to get him out of his green vest and into a new zigzag patterned vest. Obviously, we had to work closely with the directors to get just the right zigzag vest, so we went through several stages of designs on that one.”

Each of the puppets has essentially the same construction, beginning with a metal armature, which acts as the character’s skeleton. Obviously, there are variables based on size and whether the character stands on two legs or four legs or, as in the case of Gromit, whichever suits him in the moment.

The model department then molds each puppet using a special blend of Plasticine, nicknamed “Aard-mix,” which is slightly more durable than ordinary Plasticine. Audiences who remember Aardman’s first feature film, “Chicken Run,” will notice a distinct difference in the puppets used in “Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit.” Where the chickens had a smooth exterior, the models in this film were intentionally designed to retain the irregular appearance of clay, in keeping with the tradition of the Wallace & Gromit shorts-to “see the thumbprints,” as Nick Park was often heard to say.

Peter Lord expounds, “You can see the fingerprints. It tells you that they are real; they are tangible. Luckily for us, our audience has always appreciated that personal touch.”

“It’s that slight imperfection that gives it that handcrafted look,” David Sproxton adds. “I think when something is handcrafted, you register that it was made by somebody with love and care.”

Every character had to be duplicated in different poses and in various costumes-some more than others, depending on how many scenes he or she was in. For example, there were 35 versions of Wallace, and well over a dozen versions of Lady Tottington and Victor. In addition, there had to be an assortment of interchangeable and replaceable parts for each puppet, ranging from eyes and ears to heads and hands. Dozens of mouth shapes were also molded for each character so the animators could synch the characters’ mouths to the words coming out of them. Every time a mouth was changed out, the animator would have to take great care to smooth out any evidence of a seam before proceeding.

Once all the models were completed, they were turned over to the animators who would spend the next couple of years making the puppets “perform.” Guided by the vision of the two directors, supervising animator Loyd Price led a team of 30 key and assistant animators on “Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit.”

It is almost impossible to fathom the countless hours of meticulous work and the level of concentration required to make a film in the Aardman style of animation. If you think of it in numeric terms alone: there are 24 frames per second of film time, so depending on the action in a sequence, it is possible to have 24 separate poses to shoot per character for every second in a scene, each pose involving the tiniest increment of movement for body, head, arms, legs, hands, fingers, eyes, ears, mouth, and so on. In addition, the Plasticine used is malleable, so there is constant resculpting involved.

Multiply all of that by every character in every scene, factoring in the movements of any props that are on camera, and you begin to understand the task that is literally “at hand.” Perhaps the greatest testament to the patience and tenacity of the animation team is that on days when as many as 30 sets were in simultaneous operation, the optimum goal was to accomplish a mere 10 seconds of completed film.

“It is very, very slow motion,” Sproxton attests. “The animators have to know every step of the action before they start. They may even act it out themselves first…whatever it takes to get it into their brains.”

Lord adds, “It may be slow motion, but in a bizarre way, it is a live performance. An animator may have all day to do a single line that may be only three seconds long, but he only gets one go at it. With a long shot, it might take a week, and by the end of that week, you are desperate not to mess it up because you will lose a week’s work. So it may be slow, but there’s real adrenaline churning around in their bodies. There is some real fear attached to this kind of work,” he laughs.

Consistency was another element that added to the pressure for the animators. Being the title characters, Wallace and/or Gromit are in virtually every scene, so it was impossible for one animator to generate all of their actions. Nevertheless, anyone who lent a hand to either of them had to follow in the same style. Key animator and second unit director Merlin Crossingham, who was the lead animator on both Wallace and Gromit, acknowledges, “Pretty much everyone had a go at animating Wallace and Gromit at some point during the filming, purely because they are the heroes of the story and are in almost every sequence. From that point of view, I couldn’t possibly animate them all the way through alone, so we had to make sure that everybody was on the same page in terms of the movements and expressions.”

Animating Gromit posed some of the greatest challenges for the animation team, as everything he is thinking and feeling has to be expressed without a single word; it’s all in his brow, eyes and body language. His performance is entirely-and literally-in the hands of the animators, and the results even impressed Gromit’s award-winning co-star Helena Bonham Carter. “Gromit is a bit like a silent movie actor. He doesn’t need to speak; you know exactly what he’s thinking. In a way, he’s the best screen actor ever,” she smiles.

Although seen comparatively briefly, the Were-Rabbit presented key animator Ian Whitlock with a different set of challenges, beginning with the fact that he is covered in fur instead of Plasticine. If Whitlock had used his fingers to move the Were-Rabbit, he would have left impressions in the fur in various places, which, in stop-motion animation, could have looked like something was, in his words, “creeping around in there. We had to find way of handling it without actually touching it, which was very tricky.”

To solve the problem, the modelmakers fixed small levers into the back of the Were-Rabbit puppets, which gave Whitlock access points from which to manipulate them, using small tools instead of his hands. The puppets were also much larger than those of the other characters, so the inner frameworks were much heavier and more intricate. The increased weight was another obstacle to overcome.

Whitlock explains, “The thing with a bigger puppet is that it’s a constant fight with the armature, because you have to keep it under heavy tension just to lift its leg or keep the arm where it is. There’s also a lot of stress on it with the stretch of the outer fabric pulling on it, so you can’t have the armature as light as you would have liked it. You have to put quite a lot of force onto it, which is awkward when you’re trying to do something quite refined.”

3D in 3D

Computer animation and clay animation could both be termed 3D animation, although they are worlds apart in terms of execution. “Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were Rabbit” represents the most extensive use of computer animation of any Aardman film to date, long or short.

Nick Park remarks, “There are limits to Plasticine. You can’t do fog or smoke or water-I mean, you could, but it would take forever. So we went to The Moving Picture Company (MPC) to create our visual effects.”

“We’re not biased towards any one technique,” Steve Box states. “One is as important as another; it’s just a different tool that we use. We’ll use the right technique for the right job. We used CGI for things like water and smoke and dust and dirt, and it added so much to the film. The way the vicar walks down the path towards the church and the fog swirls behind him-gone are the days of cotton wool on strings. MPC did the most amazing work, and it really gives a new dimension to the film.”

The most extensive use of computer animation in the film is seen in two of Wallace’s latest inventions: the Mind-O-Matic, where visual effects were employed to add a light show of thought waves; and the Bun-Vac 6000 where, once the rabbits are sucked into the chamber, they float around in mid-air until they are released without harm to hide nor “hare.”

Getting the rabbits to fly around in the Bun-Vac 6000 without colliding was relatively simple. However, Jason Wen, MPC’s lead animator for the computer-generated rabbits, offers, “We didn’t want static bunnies to just swirl around; we needed to add a little of that `Aardman touch’ to each shot. I had to go in and hand animate all 30 rabbits-I added some cute bunny motions, like waving or grabbing at something or making their ears twirl around-to help sell the shot and make it more humorous.”

Interestingly, the biggest challenge to the computer animators was to make the computer-generated bunnies look like the more rough-hewn Plasticine models. Wen attests, “We had to study the texture closely. When the clay animators have to bend an arm or move an ear, there is no way it will look as smooth and precise as a computer generated model. We had to add those slight, random movements that happen when the animators get in there with their hands and manipulate the clay, and to simulate the subtle fingerprint impressions you can see on the clay models. It took quite a bit of research and experimenting, but I think we pulled it off.”

“It was very important to us that they gave the rabbits a Plasticine finish, and I think they replicated the rabbits really well,” Park affirms. “Even I have a hard time telling the difference.”

A Small World

Despite the influence of computer animation, “Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were Rabbit” does not compromise on the classic, old-world style for which Aardman’s most famous duo is known. In fact, while technology has revolutionized much of the animation industry, the painstaking techniques of stop-motion animation-though refined over the years-have remained virtually unchanged since the genre’s inception.

In some ways, clay animation actually has more in common with live-action filmmaking than other forms of animation, because the characters and sets are all physical, not drawn or computer-generated. Aardman has often referred to their particular style of filmmaking as “live action in miniature,” miniature being the operative word.

There are no location shots in clay animation because, short of traveling to Lilliput, it would be impossible to find locations to fit characters who range from 10- to 12-inches tall. Production designer Phil Lewis was charged with designing 30 individual sets down to the very smallest detail. Having served as the art director on the Wallace & Gromit shorts, Lewis was all-too-familiar with the design of the pair’s home at 62 West Wallaby Street. One major change to the décor was the wall of portraits of Anti-Pesto’s clients, fitted with flashing eyes that sound the alarm if rabbits are on the prowl for vegetables.

In contrast to Wallace & Gromit’s modest residence, the Tottington Hall sets were designed to be elegant and imposing. The stately home of Lady Tottington-complete with its breathtaking rooftop conservatory and lavish gardens-was mainly inspired by the National Trust’s landmark Montacute House and took eight weeks to build.

Over 100 varieties of foliage were researched and recreated to add an authentic look to the countryside gardens, woodlands and greenhouses. The greenhouses themselves feature tiny panes of real glass. Filling the gardens, more than 700 little plaster vegetables-mostly melons, pumpkins and carrots-were molded, painted and planted in the ground in anticipation of the “giant” vegetable competition.

All of the wallpaper seen in Tottington Hall and other sets was entirely hand painted. The gardening tools, as well as those seen in Wallace’s workshop are working tools, crafted in miniature.

Tremendous attention to detail was paid in the creation of Wallace & Gromit’s Anti-Pesto-mobile, which is a miniaturized Austin 35. Various scale models of the van were created, each probably costing more than the original Austin. Virtually everything about the car worked, from the headlights, to the turn signals, to the windshield wipers. The windows, doors, hood and trunk all opened and closed and the doors could even lock. The car builders even made sure that when the tires drove over the ground, they would have the proper compression.

Given the meticulously slow pace of the production, filming was always happening on multiple sets simultaneously. Directors Nick Park and Steve Box split the scenes each would cover, often walking five miles over the course of the day to check on the various sets in operation.

There were also two directors of photography, Dave Alex Riddett and Tristan Oliver, who were responsible for controlling camera movements and maintaining correct light and shadows throughout the filming of a scene, which could take days, weeks or even months. Taking a little of the pressure off of the cinematographers, camera moves are now controlled by computer, so the animators could block for the camera and know exactly where it was going to be at any given point. Nevertheless, if a mistake was made, it was virtually impossible to go back and fix it. Oliver explains, “In live action, you have the luxury of another take. With this kind of animation, you can’t do that. If you make a mistake and have to retake, you’ll have an animator cursing you because something you’ve done has cost him six days of work.”

In lighting the scenes, Riddett and Oliver were able to apply a lower level of light because stop-motion camera shutter speeds are slower than those in live action. Rather than film lights, they used theatrical lighting, which is smaller and more controllable. Carefully positioned mirrors were also used to angle light down into the small sets, and colored gels helped to create the proper tone.

For longtime fans of the Wallace & Gromit shorts, there is nothing that sets the tone better than the strains of a Yorkshire brass band playing the instantly recognizable themes composed by Julian Nott. Hans Zimmer, who collaborated with Nott as a music producer, notes, “It was easy to find the tone, because Julian had done all the groundwork with the shorts. One of the things I thought we should try to do was to amplify the feeling of the shorts through the music. We may have a bigger band than Julian used before, but it’s still the familiar sound of a Yorkshire brass band.”

Julian Nott acknowledges, “It was a very different process for me dealing with a 90-piece orchestra. It’s also almost wall-to-wall music for about 85 minutes, and if you don’t do it right, I know it can get on your nerves. But I learned certain techniques from Hans, and Hans is obviously an expert on getting it right.”

Park offers, “Julian and I met at college and he has always been the Wallace & Gromit composer. He wrote fantastic music for all the shorts, so he was an absolute must to compose the score for our first Wallace & Gromit feature. Hans Zimmer came over as a consultant and it was great to have someone of his caliber here, but the score very much reflects Julian’s take on everything.”

“The most important thing to capture was the charm of Wallace & Gromit,” Nott says.“They are very optimistic and there is not a drop of cynicism in them, which is pretty rare for a British product. But mostly it’s the charm; you can’t help loving them.”

Park agrees. “We didn’t want the music to be too big; it still had to be the Northern brass band. We didn’t want to get away from what is Wallace & Gromit. We had the production values of a feature film, and yet we maintained the handmade quality, which I think is quite important. We had a giant production behind us, but it was our duty to keep it looking as if we’re still just a couple of blokes working out of a shed in Bristol. There is a feeling of `smallness’ that was important to keep. That,” he concludes, “is where the charm is.”

These production notes provided by DreamWorks Pictures.

Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit

Starring: Peter Sallis, Helena Bonham Carter, Ralph Fiennes, John Thomson, Peter Kay

Directed by: Steve Box, Nick Park

Screenplay by: Nick Park

Release Date: October 7, 2005

MPAA Rating: G for general auidience.

Studio: DreamWorks Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $56,110,897 (29.1%)

Foreign: $136,499,475 (70.9%)

Total: $192,610,372 (Worldwide)