Tagline: Evil has reigned for 100 years…

And then she saw that there was a light ahead of her; not a few inches away from where the back of the wardrobe ought to have been, but a long way off… she found that she was standing in the middle of a wood at night-time with snow under her feet and snowflakes falling through the air… — C.S. Lewis, The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe

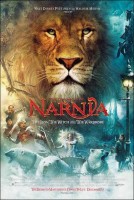

One of the most beloved fantasy adventures of the 20th Century and a timeless tale of sheer imagination at last comes to life with this stunningly realistic, painstakingly authentic adaptation of C.S. Lewis’ masterpiece. Years in the making, this is the first-ever big-screen adaptation of the powerful classic that has sold more than 100 million copies worldwide.

Walt Disney Pictures and Walden Media present The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, in which four young adventurers playing hide-and-seek in the country home of an old professor stumble upon an enchanted wardrobe that will take them places they never dreamed.

Stepping through the wardrobe door, they are whisked out of World War II London into the spectacular parallel universe known as Narnia – a fairy-tale realm of magical proportions where woodland animals talk and mythological creatures roam the hills. But Narnia has fallen under the icy spell of a mad sorceress, cursed to suffer through a winter that never ends by the White Witch Jadis. Now, aided by Narnia’s rightful leader, the wise and mystical lion Aslan, the four Pevensie children will discover their own strength and lead Narnia into a spectacular battle to be free of the Witch’s glacial enslavement forever. Touching on eternal themes of good and evil, and of the power of family, courage and hope in the darkest moments, The book is a classic fable for our times.

Years in the making and meticulously created by director Andrew Adamson to match C.S. Lewis’ own vision of Narnia, The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe marks the live-action debut of New Zealander Adamson, who came to fore bringing worldwide audiences the loveable green ogre at the heart of the Oscar-winning “Shrek” and “Shrek 2.” Adamson carries to the film a passion for Lewis’s story that began in his own childhood – one that now meets up with extraordinary advances in motion picture technology. The vast scope of the director’s vision of Narnia is brought to life through a mixture of moving human performances and cutting-edge, photo-realistic techniques in CGI, animation and prosthetic makeup that turn the wildly creative worlds and characters Lewis forged into something heart-stoppingly close to reality.

Says Adamson: “The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe has taken millions of young minds into realms of fantasy – so the enormous challenge as a filmmaker was to try to re-create those worlds in a way that might live up to and even exceed people’s imaginations, that could truly transport you to another time and place. ou couldn’t have made this film 5 years ago. You couldn’t have made a photo-realistic lion like Aslan five years ago, or joined animal legs unto a human body realistically as we did with centaurs and minotaurs five years ago. Now is the right time to be making this story.”

Adamson co-wrote the screenplay with Emmy Award-winner Ann Peacock (“A Lesson Before Dying”) and Emmy winners Christopher Markus & Stephen McFeely (“The Life and Death of Peter Sellers”). The film was produced by Academy Award-winner Mark Johnson (“Rain Man,” “Bugsy,” “The Notebook”) and Philip Steuer (“The Alamo,” “The Rookie”). Adamson and Perry Moore are the film’s executive producers, with C.S. Lewis’ stepson, Douglas Gresham, serving as co-producer.

The film’s stellar cast features Tilda Swinton as Jadis, the powerful White Witch who plunges Narnia into a frozen winter of war and discord. A quartet of rising young talents take on the roles of the Pevensie siblings who journey through the wardrobe: newcomer Georgie Henley is Lucy, the youngest and first to enter enchanted Narnia; Skandar Keynes is Edmund, who falls under the seductive spell of the White Witch; teenaged Anna Popplewell is Susan, the practical sister who remains skeptical about Narnia; and William Moseley plays Peter, the eldest sibling, who becomes a true leader as their adventures mount.

Through The Wardrobe Door: An Introduction to Narnia

“The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe is an adventure the likes of which no one has ever been through, yet everyone who is, or ever was, a child would love to be a part of.” — Producer Mark Johnson

In 1950, the scholar, critic and writer C.S. Lewis published The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, the first of his seven-volume series, The Chronicles of Narnia, and established a modern legend. A long-time fan of what he called “fairy stories,” Lewis had set out to write a series of fantasy tales for children, but his creation turned out to be much larger and grander than even he had foreseen. Adults and children alike fell in love with his stirring, action-packed adventure that was set in the middle of World War II bombing raids yet transported readers into an alternate and far more enchanted universe of mythological creatures waging an epic battle between good and evil. Meanwhile, critics were impressed with Lewis’ rare ability to forge a completely believable, imaginary world – one with its own history, geography, culture and myths that nevertheless reflected the struggles.

Profoundly affecting its fans, The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe went on to develop an enduring, worldwide readership and to become a staple of family libraries across the planet. The entire Chronicles of Narnia series – which also includes Prince Caspian, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, The Silver Chair, The Horse and His Boy, The Magician’s Nephew and The Last Battle — took the publishing world by storm, eventually selling over 85,000,000 books in 29 different languages, making it second only to J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter tomes as the most popular book series ever. Indeed, Rowling has cited C.S. Lewis’s Narnia as one of the inspirations to her own contemporary stories of magic and adventure.

From the beginning, C.S. Lewis had wanted the experience of Narnia’s wonders to be open to people of all background and ages. Explains the film’s co-producer, Lewis’ stepson Douglas Gresham, who grew up knowing Lewis and his writing intimately: “C.S. Lewis’ mandate, his main idea about writing for children, included the theory that if a book is worth reading when you’re five, it is still equally worth reading when you’re fifty. So The Chronicles of Narnia was intended to be read to children and by children and also to be read by adults with great joy even to the last days of their lives.”

Along with a few other rare stories such as The Lord of the Rings (written by Lewis’ close friend and contemporary J.R.R. Tolkien), The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe became the equivalent of a foundational 20th century fable. It was one of those timeless adventures that equally fascinated grade-schoolers, grown-up readers and the most sophisticated literary scholars intrigued by its metaphors and spiritual allegories.It soon saw many incarnations in stage versions, as a British television series, as an animated film and even in a BBC version created almost entirely with puppets.

But no one dared to attempt to bring Lewis’ land of Narnia to life with real actors and sets, perhaps because it simply seemed too vast and overwhelming an undertaking. Only recently, as technology has at last begun to catch up with Lewis’ far-reaching imagination was it even possible to imagine re-creating Narnia with the thrilling realism director Andrew Adamson brings to the story.

C.S. Lewis’ stepson, Douglas Gresham — the creative and artistic director of Lewis’ estate and the C.S. Lewis Company — always believed a motion picture of Lewis’ masterwork would one day become reality. He stuck by the dream of bringing the story to life in a way that would honor Lewis’ enduring creation for decades. “I’ve been working on seeing a movie made of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, one way or another, for probably twenty-five or thirty years,” Gresham notes. It was not until Gresham was approached by Walden Media that the project truly began to take shape. “The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe was my very favorite book as a kid, like it was for so many other people,” notes executive producer Perry Moore, who was then a film executive at Walden Media. “I always thought it was the perfect fit for Walden.”

From the start, everyone at Walden and subsequently at Disney was committed to remaining steadfastly true to the spirit of C.S. Lewis’ story — without adding manufactured twists to a story that has continued to inspire generation after generation. “On the very first day that we sat down with the estate, we assured them that we were going to do an absolutely faithful adaptation,” Cary Granat of Walden Media explains. “Perry and I and, most importantly, Phil Anschutz [Walden Media’s founder], were devoted to that vision. We weren’t looking to put modern-day spin on this piece, but to honor it as a classic of all times.”

Sums up Gresham, for whom the journey to bringing his stepfather’s work to the screen was profoundly personal: “The story of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe is so true, so honest, so straightforward, we felt certain that the less we messed around with it, the better movie we would make. The first and most important thing about getting this movie made properly was to get the right people involved. Finding Andrew Adamson and bringing him on as director was key.”

Enter Andrew Adamson: A Visionary

“Unlike Tolkien, who was very specific, Lewis left a lot to your imagination. So we had the enormous challenge of not only creating Narnia, but of trying to fulfill people’s expectations, to bring the film up to the level of their own dreams and fantasies.” — Director Andrew Adamson

To take on this first live-action cinematic telling of C.S. Lewis’ masterpiece, the producers knew they would need an unusually creative – not to mention hugely energetic – director; someone who could seamlessly marry the real world with a fantasy realm of tremendous scope in a way that would be at once believable and emotionally powerful. It would require someone with definite savvy in high-tech filmmaking, someone with a vivid fantasy-oriented imagination, yet also someone with the sensitivity to evoke a tale that is at heart, about children, family and the powerful notion of bringing good back into the world. Most of all, it would require someone with a passion for Lewis’ highly distinctive style of fantasy storytelling – at once simple, magical and resonant.

At first, the search naturally focused on some of today’s best-known directors, but then along came an utterly unexpected candidate: Andrew Adamson. One of Hollywood’s preeminent animation directors and visual effects artists, Adamson’s directorial debut, the animated global hit “Shrek,” had captivated audiences with its fairy-tale charm, humanity and visual imagination. Despite the fact that he had never directed a live-action film before, Adamson came to his first meeting bursting with a storm of creative ideas that left the producers wowed by his personal passion for the project. He seemed to have a deep inner connection with Lewis’ Narnia that the producers knew was essential to imbuing the film with magic.

“He talked so passionately about the emotion and the themes of the piece,” Cary Granat recalls, “and from those conversations we knew he was the guy. I’ve worked with a lot of different filmmakers but I have never seen somebody who was so completely in tune with a specific vision for a movie. After one meeting with Andrew, Perry and I were both in agreement that this was the right person.”

Adamson’s excitement was inspired by his own memories of being an 8 year-old boy who was whisked into Narnia and was never quite the same again. “I read all seven books continuously over a period of a year or two, just read them over and over,” he recalls.“I basically existed in this world of Narnia for a time. I remembered it as this huge, vivid story with a massive battle between good and evil and a whole menagerie of mythological creatures – and I wanted the chance to bring that world to the screen.”

Stirred by his childhood remembrances, Adamson started from the premise that Narnia had to come off as one hundred percent real – no matter what it would take cinematically to achieve. “What is Narnia?” he asks. “That’s an interesting question and key to our approach. I don’t see Narnia as just a figment of the children’s imaginations, a place that they retreat to in their minds to escape World War II. Rather, I believe in Narnia as a true alternate universe. There are many parallels to our world and there are many differences, but the main point is that it is real.”

He continues: “So my approach to the movie was that it’s not quite like ‘The Wizard of Oz’ or ‘Peter Pan,’ where you realize in the end that the story all happened in someone’s imagination. When Lucy goes through that wardrobe and steps into a world, I wanted that world to be completely believable, as if it was another country you might visit. It had to be a whole Narnian reality unto itself.”

It was clear from the start that Adamson’s ideas for the film were vastly ambitious, but Adamson was only further excited by the risk of tackling one of the most massive projects of his, or anyone’s, career — one that would demand constant creativity in every aspect of filmmaking. The director began on the page — by collaborating with screenwriting partners Christopher Markus & Stephen McFeely (who went on to write the Emmy winning “The Life and Death of Peter Sellers”) and polishing the original screenplay by Emmy winner Ann Peacock, putting the emphasis first and foremost on storytelling.

“We approached it as a story that is very much about themes of betrayal, forgiveness and loyalty. It’s about a family who feels disempowered by the terror of World War II and then finds their power again in Narnia,” Adamson remarks. “It’s a story about four kids who enter this land where they’re not only empowered, but where they’re ultimately the only solution to the war in that land. And it’s only through unity as a family that they can actually triumph. And that’s where we began.”

As they re-read the book, the screenwriters were surprised to find that the text of the story itself was actually far more brief than they had remembered. “Most people recall it as a denser, fuller book than it actually is. That’s a tribute to Lewis. He was a master at tweaking kids’ imaginations enough where they could generate the rest of the story themselves,” explains McFeely. “So we needed to flesh parts of it out, take the image we had as kids and make that feel very real.”

Adamson adds: “I too remembered it as this epic story. So the first thing that I did was to write everything that I remembered from reading it as a child — how I imagined the battles, how the mythological creatures might fight with each other, who the characters are, right down to the color schemes. I put down a stream-of-consciousness of everything I thought the movie should be and extrapolated from there.”

The ideas, however, were all sparked directly by the writing itself, by Lewis’ endlessly imaginative frame. “All the themes, all the messages that were important to C.S. Lewis are present in the movie, and it is, I hope, a faithful envisioning of what Lewis was imagining when he wrote the book,” he comments. “It’s both an epic story of a battle between good and evil, and an intimate family drama about a fractured family that has to mend itself.”

Sums up producer Mark Johnson: “I think audiences will take away the most positive messages of belief, strength and family. But, in the process, they will also go on an original, exciting, unexpected ride. People ask it is like ‘Lord of the Rings’ or ‘Harry Potter’? The answer is no, it is its own world, and yet I think the sensation of seeing those movies will be akin to the sensation one will feel in seeing this movie.”

Introducing Narnia’s Explorers: The Pevense Family

At the heart of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe are the many spellbinding characters and creatures who came to life in C.S. Lewis’ beloved tale – from the four young children who are transported from war-torn London into Narnia to the incredible mythical menagerie of fauns, centaurs, giants, satrys, dwarves, minotaurs, minoboars and talking animals they meet on their life-changing journey.

The filmmakers’ first and most vital task was to start with the cornerstone of humanity in the film — the four Pevensie children, who take the audience along with them as they discover that a mysterious old wardrobe door is a portal into a land like no other. As casting began, the filmmakers knew one thing: it was essential that the children be as utterly, viscerally real as Narnia is fantastical.

Executive producer Perry Moore explains the approach taken in the search for the children: “What makes this story so unique is that it’s about real people. When you think of Narnia, you think of creatures, effects and spectacular dream-lands. But this is all grounded in the reality of a true family. So while there are a lot of great child actors in Hollywood, we made it very clear that we wanted real kids!”

The filmmakers sought the services of veteran casting director Pippa Hall and thus began a two-year hunt throughout England, during which Hall visited endless grade schools, youth clubs and drama groups, interviewing over 2,000 children for the four roles. “I took a video camera everywhere, sitting kids down to get them to talk about themselves, what their favorite books were, what films they liked,” Hall recalls. “I would then send Andrew loads of tapes and he’d watch them all and that’s how we cast the Pevensies.”

Peter Pevensie

The eldest of the Pevensie kids is Peter, who leaves London a child yet becomes a brave, grown-up leader fighting for the forces of good while in Narnia. To bring Peter to life, Pippa Hall always had in mind eighteen-year-old William Moseley, who makes his feature film debut. Hall first saw Moseley seven years ago and had never forgotten him. “William’s is a fairy-tale story,” Hall elaborates. “I met William when he was eleven, when I was casting another film in Gloustershire, near where he lives. He was too old for that part, but I still thought he was extraordinary, that he had something special. I thought of William as Peter as soon as I read the script.”

Being about the same age as his character, Moseley immediately related to Peter’s transformation in the course of his adventures in Narnia. “To put it simply, when Peter steps through the wardrobe, he’s a boy. When Peter steps back out of the wardrobe, as the story finishes, he’s a man,” the teenager says. “And, for me, I think I also became a man throughout the making of this film. Like Peter, I’m the oldest in my family. Like Peter, I strive a lot of the time for what’s right, what’s just. I think that’s the reason each of the kids was cast for these parts — we’re so like the characters we play.”

“What really impressed me about William is that he grew into a young man as we were making the film,” Adamson chimes in. So, I basically saw William grow from this fifteen-year-old boy to this young man, this real warrior, just as Peter Pevensie does in Narnia.”

Susan Pevensie

For the role of Susan, the beautiful, down-to-earth elder daughter, who tries to be the responsible one during the children’s journey through Narnia, the filmmakers selected the most seasoned cast member among the four children — London-born actress Anna Popplewell, whose credits already include “Girl with A Pearl Earring,” “Mansfield Park” and “The Little Vampire.” Popplewell was among the very first performers put on tape by casting director Hall, and quickly caught co-producer Douglas Gresham’s attention. “I looked at these kids and immediately picked Anna for Susan,” he says. “She is not only beautiful, she’s also extraordinarily talented, and she brought the role to life in a really original way.”

“In many ways, Anna Popplewell, playing the part of Susan, had the hardest part of the four kids,” producer Mark Johnson continues. “Her character has to be the reasonable, sensible one, but Anna presents her in a dynamic way that allows the audience to really feel and comprehend the danger and apprehension that these four children experience in Narnia. It’s a testament to how good Anna’s performance is that we expanded the part of Susan. We gave her more scenes, more dialogue, because Anna made her character so integral to the adventure of the movie.”

Popplewell, who recently turned 17, was very clear on what Susan goes through on an emotional level in Narnia. “Each of the characters in The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe has their own journey, and Susan’s no different,” she says. “Like Peter, she feels the obligation of looking after her younger brother and sister, and it’s something that has made her grow up too fast – being saddled with all that responsibility. When she comes to Narnia, she thinks she’s too grown up to believe in it. But, through this adventure, she becomes more open to the idea of being in this magical land. By the end, it’s changed her for the better and she becomes unafraid of being a child. It’s a real journey for her.”

Edmund Pevensie

Young Edmund is the most boisterous and mischievous of the Pevensie family and, once in Narnia, finds himself dangerously tempted to join forces with the White Witch. To portray the playful little rascal who learns to do the right thing, the filmmakers struggled to find the right actor, and didn’t discover Skandar Keynes until the very last moment.

“Edmund is probably the most developed character in the book, and he was in some ways the easiest to know what to look for, but the hardest to find,” Adamson comments. “Then along came Skandar and he was, really bright, funny, energetic, just full of beans, and very wicked. He had a wonderful darkness in his eyes and was mischievous, sweet and adorable all at the same time. Those were the character traits I really wanted Edmund to have – to be able to pull off this darkness and still be lovable.”

Hailing from a London family related to Charles Darwin, and the son of author Randall Keynes, Skandar impressed everyone on the set with his youthful smarts and wisdom. Now 14, he had first read The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe as an eight-year-old, which is also when he was first completely taken by Edmund. “I prefer my character over all the others. I really think I have the best character,” the young actor says with his typical bravado. “Of course, he’s a lot like me. He is the tyrant of the family, which I am, and, yep, he succumbs to temptation very easily. Edmund is the black sheep of the family, always teasing Lucy. But, in the end, Narnia makes him good. He goes through the most radical change, starts to appreciate his family. The adventure really changes him into a better person.”

Lucy Pevensie

Completing the quartet of children is ten year-old Georgie Henley in the role of Lucy Pevensie, the youngest Pevensie and also the most optimistic, open-hearted and brave of them all, and who Adamson considers one of the story’s most important characters. “Lucy is the pure heart of the book. She’s the one who first enters Narnia, the one who has to deal with the disbelief of her siblings, and the one who has to have the spunk and energy to still believe in herself,” he says. “Georgie Henley was just that. I knew from the moment I saw her on tape that she was Lucy, she was just so believable in her very first audition.”

Pippa Hall discovered Henley out of the blue on a visit to a school in Yorkshire. Despite having no acting experience, Henley had something much more important – she was an unusually intelligent, articulate and emotional child with a huge love of books. Later, she became a constant surprise on the set. “She was so original in her approach to the part that she made us see the dialogue in new ways, ways we hadn’t even imagined it before,” comments producer Mark Johnson.

Like the other children, Georgie saw an immediate link between herself and her character. “Lucy is quite a lot like me in a way so it was very easy to slip into her character,” she says. “Lucy’s the youngest of the four Pevensies, and nobody takes her opinions seriously as the story begins. When she opens this wardrobe, she’s in a new world and she feels as though her feelings mean something there.”

With the children cast, Adamson’s next task was to bring them together as a close-knit family unit. “I wanted to create a strong family dynamic – but I couldn’t have hoped for it to go as well as it did,” he notes. “I’m sure a part of what developed between them was because they were all so far away from home that they kind of glommed onto each other. Part of it was the mix of personalities that I picked. Yet it was almost magical how they began to seem like a real family of siblings during production.”

To further help the children stay in the rhythm of the story, Adamson chose to shoot The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe entirely in chronological order – so that each new scene brought the young actors deeper into their characters and further into their discovery of Narnia.

Rounding out the Pevensie family is the family matriarch, played by New Zealand actress Judy McIntosh. It is she who must make the agonizing decision of sending her four children out to the country during the dangers of the London blitzkrieg. For McIntosh, a mother of three children herself, the small role was a very moving one, integral to the story’s impact. “Mrs. Pevensie is there to highlight the plight of these British evacuees during the War,” notes the actress “I think she provides an opportunity to kick-start the film with an emotional impact. When she says goodbye at the train station, she gives the children the responsibility to go out and make those adult decisions that she would normally have made for them.”

Before Adamson led his film family into the magical world of Narnia, he cast two other key roles for the film’s opening in war-torn England — veteran New Zealand actress Elizabeth Hawthorne as Mrs. MacReady, the stern caretaker of the professor’s country home where the children are evacuated; and Best Supporting Actor Oscar-winner Jim Broadbent as Prof. Kirke, whose home houses the magical wardrobe. With the human elements of the film in place, it was time to move into the magical realms of Narnia.

Into Narnia: Casting and Creating Narnia’s Iconic Creatures

Once they cross the threshold of the wardrobe, the Pevensie children find themselves in a world filled with extraordinary creatures that were previously unimaginable to them – and some of whom become their good friends and heroes. To forge these now-iconic creatures from The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe required not just one or two filmmaking techniques but a sophisticated and complex mix of human acting performances, practical effects and digital wizardry.

The first steps to their creation began with meticulous casting. While casting director Pippa Hall concentrated on finding the four key child actors for the Pevensie kids, her colleague Gail Stevens, was secured by the production to audition talent for the “non-human” roles that make up so much of the film.

Mr. Tumnus, The Faun

The very first “non-human” role cast was that of Mr. Tumnus – the shy, retiring, half-man-half goat who befriends Lucy but is forced to serve the evil plans of the White Witch. The faun was C.S. Lewis’ original inspiration for the creation of Narnia – he once said that it “all began with a picture a faun carrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood” – so the filmmakers knew the part was vital to bringing Narnia to life. They found the fabled qualities they were seeking in rising Scottish actor James McAvoy. “James captured the sinister duality of Mr. Tumnus,” says Andrew Adamson. “He also has the perfect face for the role. Most of all, he had this incredible connection with Georgie, which was so important to the story.”

“I loved the books when I was a child, and to remember how they made me feel back then was exciting,” McAvoy relates. “Mr Tumnus was always one of my favorite characters so to play him was a big honor.” For McAvoy, the fascinating part of Tumnus is that he becomes morally torn in his mission to kidnap Lucy for the White Witch “He’s forced by circumstance to do something against his will,” says McAvoy. “And therein lies the duality that Andrew and I talked about. Tumnus is conflicted because in the process of kidnapping Lucy, he forms a bond with her and they become close friends. Ultimately, he’s forced to look at who he is, and what he wants and what he can live with, which is a very unexpected thing for him.”

To morph from a 26-year-old modern young man into a century-plus old mythological creature, McAvoy had his own trials to bear — enduring over three hours daily at the hands of one of Hollywood’s most seasoned makeup magicians: K.N.B. EFX Group co-founder Howard Berger. “Once they cast James, we flew him over from England for a life-casting,” Berger explains. “Andrew had a very specific vision in his head of what Mr. Tumnus should look like. He wanted to recreate the Mr. Tumnus that was in his head when he was a child and I think we were very successful.”

Berger continues: “For James, we sculpted a head piece that included little radio-controlled ears that actually move, and horns attached to a skull cap. Then there’s a nose piece, a forehead piece and hair pieces, including a wig, chops, beard, eyebrows, and body hair. It took two of us over three hours to put all that on James every day. It was a very intense process.”

In addition to enduring the grueling grind of his daily makeup, McAvoy spent several weeks perfecting the voice and walk he used to bring the film’s first Narnian creature to life. “In folklore, fauns were followers of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and intoxication. They were merry, mischievous creatures and I wanted to reflect that,” McAvoy explains. “There’s also a very English feel to the way Tumnus is written. That’s something C.S. Lewis did on purpose — undeniably wrote him in a very certain type of English voice.. I took the tone of Mr. Tumnus’ voice from the goat in him, but the accent came from the man half of him.”

From the waist down, Tumnus is all CGI, but in order to best emulate how a man-goat might walk, McAvoy learned to walk on his toes for the cameras. “They couldn’t have me walking around as a normal guy because my upper body would look strange on these hind goat legs,” he remarks. “So, I had to walk about a million different ways, then look back on the computer and see which one method worked!”

To complete the transformation from man to faun for the film, Adamson relied on the talents of the visual effects wizards led by VFX supervisor Dean Wright. The process, which Wright simply calls ‘leg replacement,’ was first used in Robert Zemeckis’ 1994 Oscar winner, “Forrest Gump” (for the character of Sgt. Dan, the maimed Vietnam vet played by Gary Sinise). Wright, employing recent and more sophisticated computer software, used “green screen pants” on McAvoy to create the illusion of a two-legged goat, matching the movement of his computer graphics to that of McAvoy’s gait.

Even with all the preparation needed to bring Tumnus to life, director Adamson insisted that, like a bride before her wedding, actress Georgie Henley should not get a glimpse of what the faun character looked like until the last possible minute, so her reactions of wonder and delight would be entirely authentic. “Andrew always wanted to amaze me so he kept me from seeing the faun and the White Witch so that I would react in a very convincing way,” says Henley, “and it worked!”

Jadis, The White Witch

The greatest villain in Narnia is Jadis, the seemingly invincible White Witch who has cursed the one-time paradise to endure an eternal winter. To play the nefarious and chilly role, the filmmakers embraced executive producer Perry Moore’s suggestion of veteran Scottish actress Tilda Swinton, one of the mainstays of European cinema. “I’ve been a fan of Tilda since I saw her in ‘Orlando’,” Adamson says of his leading lady, whose pale complexion and ethereal beauty added dramatic dimension to the imposing creature she plays in the film. “In addition to her physical stature, which suits the character perfectly, she brings a strength, intensity and intelligence – all characteristics I wanted for the White Witch. After all, she has to be as smart, as strong and as intense as Aslan the Lion in her confrontations with him.”

He continues: “I think the guiding principle for both of us was avoiding cliché. When C. S. Lewis wrote this book, the character of the White Witch was somewhat original but that was fifty-five years ago. Now we have seen so many evil queens and witches, from Cruella De Ville onwards. So we wanted to stay away from cartoonish, cackling figures. Instead, what we wanted was a more human type of evil, something a little darker and more real, and I knew Tilda had the sophistication to pull that off. It was a big challenge. Ultimately, Tilda created a really convincing witch who evokes pure icy coldness.”

Unlike most of her cast-mates, Swinton came to the story completely fresh. “I’m one of the few people who was brought up in the UK who didn’t read any of the Narnia books as a child,” Swinton confesses.”So, I came to them entirely because of Andrew Adamson who asked me to be in this film. I then read the stories to my six-year-old children. They were the acid test. When they thought it was a good idea, I began to take the idea of the film seriously. Of course, it’s a tall order to play the epitome of all evil. I just might have children backing away from me for the rest of my life!”

It was also a tall order for an actress used to portraying the finer nuances of human emotion to take on a character for whom emotion is a foreign concept. “Jadis is not human, you have to remember. She has no feelings about anything,” Swinton notes. “She’s not really comprehensible on any normal level. She has created Narnia as a reflection of her own state of mind, freezing it into perpetual winter — no spring, no Christmas, no progress, no good, a pretty joyless place, until these children begin to turn it around.”

Swinton became closely involved in creating the look of the White Witch, which is so integral to her character. “We agreed that she should look modern and quite attractive in her own way. I thought about my favorite fantasy beauties like the Good Witch in ‘The Wizard of Oz,’ that played away from the cliché of a villainess. I didn’t want to have any of the standards: black hair, red lips or black eyeliner.”

She continues: “The idea we worked on with the costume was that it would be like a mood thermometer, that it would morph with her mood. She never changes dresses but the dress itself changes shape and color according to how things are going for her. When she’s at home in her ice castle, it puffs out like a ball gown, and when things are getting a little bleaker, the dress gets tighter and darker. And when things get really dark for her in the story, it goes completely black.”

In designing the gowns, replete with handmade lace, for Swinton’s character, costume designer Isis Mussenden envisioned “seven different gown changes for Tilda to physically represent her diminishing powers. As spring takes hold of Narnia, it melts away the frost and drains away the White Witch’s powerful hold on the frozen landscape.”

Ultimately, Swinton fell just as in love with Narnia as those who had first encountered it in childhood. She says: “The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe began to remind me of great family films that I grew up with, like `The Railway Children’ and ‘The Wizard of Oz.’ It’s a classic story in that it has an old-fashioned quality but at the same time it feels entirely modern.”

Aslan, The Lion

The White Witch’s greatest rival in Narnia is Aslan, the wise and majestic lion who sang Narnia into existence and once served as high king of the land. To create this towering character, so beloved as a hero by so many, Adamson turned both to CGI wizardry and to acclaimed, Academy Award-nominated actor Liam Neeson, who creates Aslan’s charismatic personality through his voice. “Aslan is all-powerful and all-knowing, yet still has a very human vulnerability,” observes Andrew Adamson. “I think C. S. Lewis used a lion for Aslan because he represents something that’s both fearsome and awesome. He’s the epitome of strength and power, but he’s not just a dream lion. He’s flesh and blood and that was very important to our conception.”

For the filmmakers the key to creating Aslan was to use the latest digital magic to make him look like he isn’t digital at all – but a true beast of the forest, albeit with disarmingly human and intelligent eyes, right down to his thunderous roar. “We hope Aslan will be the most photorealistic computer-generated animal yet seen in a motion picture,” says producer Mark Johnson. “We want audiences to wonder just how we were able to get this dangerous beast to interact so beautifully with children actors.”

It took VFX supervisor Wright some 700 individual VFX shots and almost 2 years to breathe life into the Aslan who graces The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe. He had his work cut out for him.”There ‘s a very fine line when taking an animal character and having it talk and relate to humans,” Wright admits, “and we definitely didn’t want to cross the line of becoming cartoonish. The photorealism and the movement had to have almost a hyper-reality to them in that Aslan acts just like a lion yet can do more than you expect a lion to do, and that was our challenge.”

Vital to Wright’s work was allowing Aslan to speak in a natural, organic manner which meant mapping the movement of his speech unto the whole musculature of the animal and not just his mouth – creating a realism that takes the animation that brought “Babe” and other talking animals of recent cinema to new heights. Comments Adamson, “It was essential to me that the animation in this film not be caricatured. I wanted the moment where Lucy nuzzles up to Aslan to have the power of ‘oh my gosh, that little girl is snuggling up to a real lion.’ It had to have the kind of weight and believability that you don’t usually see in animation. We’re very lucky that technology has just reached the point where this was a possibility.”

Meanwhile to match a voice to the mighty beast, Adamson turned to leading screen star Liam Neeson because, he says, “Liam has such beautiful depth and resonance to his voice. He can exude such great warmth and compassion while also possessing a ferocious strength. He completely believes in the character and it comes across in a performance that adds the final touch in bringing him to life.”

In addition to the primary CGI work used to forge Aslan in the computer, Adamson also relied on K.N.B.’s Howard Berger to provide three life-sized animatronic lions for a few key scenes. “One version is a full-size Aslan that was utilized for stand-in work, so Dean’s digital crew had a special reference point when filming on the set,” explains Berger. “Next, we built a version of Aslan for the Stone Table, which was a full-scale, eight-foot lion puppet, just a magnificent piece of work, with a radio-controlled head. It breathed and did all this amazing stuff. Finally, we created a riding version that Susan and Lucy rode against green screen. It was this enormous, hulking thing that weighed a good 500 pounds, if not more.”

While constructing these colossal puppets, Berger too aimed for palpable realism. His final test was to see if the young actors reacted to his Aslan puppets with awe. “I really wanted the actresses not to think it was a puppet. I didn’t want them to think for a moment it was just a prop or a makeup effect, but to react to it as if it was right out of the zoo,” Berger notes. “When we saw that happening, it was wonderful. That was always Andrew’s vision of Narnia – a place just as real as London, but a lot more magical.”

Journey to Narnia: The Film’s Design

The world of Narnia has, up until now, existed only in the imaginations of millions of readers. With his characters cast, director Adamson was faced with the massive, daunting task of bringing Narnia’s geographic world – from its wooded coves, magical lampposts and beaver lodges to the iced-over castle at Cair Paravel — to palpable life so that one could believe with all their senses that they truly exist.

Before hammer was ever put to nail, before paint was put to brush, before saw was put to wood, Adamson pre-visualized more than half of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe inside a computer. With this tremendous advantage, and armed with his intimate knowledge of Narnian history and lore, next began the physical work of creating Narnia’s famous locales as life-sized sets. Adamson sought out two unique talents to bring the physical reality of Narnia alive. He says: “I couldn’t have done it without production designer Roger Ford, who created magnificent sets that exceeded everyone’s expectations, and D.P., Don McAlpine, who did a wonderful job lighting the world of Narnia.”

In early conversations with production designer Ford, Adamson explained his concept for the look of the film, which he hoped would match what he had seen in his mind’s eye as a child – an incredibly real and unsparing vision of a bleak WWII London turning into a doomed, wintry, fantastical Narnia and then, ultimately into an incredible burst of lush, magic-filled spring full of renewed life and hope. Ford knew that trying to capture the sheer inventiveness and wonderment of a child’s imagination would be a huge challenge. “I think the most difficult thing about creating a film that is also for children is that you have got to surprise them,” he says. “You’ve actually got to go further than their imagination goes, which is not an easy thing. At the same time, it’s a dream project for a designer.”

The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe marked the second collaboration between Ford and Don McAlpine, who shot Ford’s sets on P.J. Hogan’s 2003 fantasy film, “Peter Pan.” But this film was like nothing they had done before. McAlpine’s creativity was pushed to new edges as he tried to shoot a world covered in a glacial sheen of ice. “It was a series of experiments, and something totally new to me,” the director of photography remarks.”Ultimately, I think it’s something totally original that we tried. Ice has always been a problem in films. They’ve tried it in many movies, ‘Vertical Limit’ being one, but I think we took it one step closer to reality and created something that will be very visually exciting.”

The Oscar-nominated Ford (“Babe”), a veteran designer whose career dates back to the cult favorite, “Dr. Who,” designed and constructed almost three-dozen set pieces for the production – many of them influenced by the original pen-and-ink drawings created for C.S. Lewis’ 1950 novel by illustrator Pauline Baynes. Collaborating closely with one of the industry’s finest art directors, Australian native Ian Gracie (“Moulin Rouge,” Star Wars: Episode III”), Ford recruited a team of thirty for his art department and a construction crew surpassing 300 carpenters, painters and other craftsmen, the largest the designer had ever assembled in his 40-year career.

At New Zealand’s decommissioned Hobsonville Airbase, the designers transformed old airplane and helicopter hangars into sound stages that harbored such spectacular sets as the Stone Table, where Aslan appears to have been defeated; the White Witch’s magnificent courtyard of creatures turned to stone; the bustling London train station, patterned after famous Paddington station, where the four Pevensie children are evacuated during the London blitzkrieg; and Cair Paravel, the great Narnian castle.

The design team also utilized Kelly Park, an old equestrian center north of Auckland, where Lucy, and the entire film company, took their first footsteps into the snowy Narnian landscape on a set the size of a rugby field. This massive set, which would eventually be transformed into nine different areas of Narnia, challenged Oscar-nominated cinematographer Don McAlpine to come up with an innovative grid of some 250 space lights, hanging from the building’s rafters, to illuminate the magical, imaginary land.

Conifer Grove, a woodsy campground neat Manukau Harbor, was chosen by the filmmakers for the White Witch’s camp, where K.N.B.’s Berger and his troops transformed Kiwi extras into minotaurs, minoboars, cyclops and other creatures. Henderson Studios, home of the 1TV series “Hercules” and “Xena,” housed such spectacular builds as the interior of Mr. Tumnus’ house; the beaver lodge; the White Witch’s dungeon; an exterior set called “the frozen lake,” where Ford’s crew created a gimbal system of mini-icebergs which swayed and flowed under the weight of Lucy, Peter and Susan while fleeing the clutches of Maugrim’s wolf pack; the White Witch’s Great Hall; and the wardrobe room, a dusty attic which houses the essential set piece of the book’s title. Ford elaborates on some of his favorite designs:

The Lamppost

The lamppost that lies just on the other side of the wardrobe becomes the children’s introduction to Narnia. It was also one of Ford’s most beloved sets for its fairy-tale nature. “It was just magical,” the designer comments. “You come out of this wardrobe, it’s snowing, it’s cold, and you don’t know where you are. Then, in the middle of the forest, there’s this lamppost growing with great roots around the bottom of it. Not woody roots, but cast iron roots. It’s a very evocative introduction to Narnia.”

“We actually brought the lamppost in from the U.K.,” Ford continues. “It’s a casting of an original London lamppost. We cast several versions of it. We wanted it to be very authentic so we also got the proper gas fitting which appears in the film. To me, it’s one of the most iconic images in the book. You have the faun with an umbrella in the snow, which was C. S. Lewis’ first inspirational image for writing the book. And then you have the lamppost, which occurs very early in the story. As the children pass the lamppost, it’s kind of an eternal light that leads them into Narnia. What we created was exactly how I imagined the lamppost in Narnia to be.”

The Wardrobe

No ordinary piece of furniture, the carved wooden wardrobe the Pevensie children stumble upon in the professor’s house is actually an ancient doorway into a parallel universe. Another of the story’s most iconic images, the creation of the wardrobe was vital to the film’s design. “The wardrobe was a major project,” Ford says. “It’s probably the most important prop in the film. I mean, how many expectations of children are resting on what the wardrobe will look like? We knew it was a great responsibility.”

He continues: “First, we found a wardrobe that C.S. Lewis actually owned in a museum in the States. It’s a big, oblong, square wardrobe with a carving on it, and quite dark – a Jacobean style wardrobe. So that gave us the idea that our wardrobe shouldn’t be too Baroque or decorative. It should have a simplicity about it. Next Andrew very cleverly came to the conclusion that this wardrobe should have one large door. It’s a portal after all, to another world. So ours has one entrance that the children find irresistible.”

Ford also took inspiration from the sixth book in The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, The Magician’s Nephew, which reveals that the wardrobe was originally made of apple wood, and attempted to replicate that dark, rich wood. “Knowing that C.S. Lewis’ wardrobe was heavily carved, Andrew and I also wondered what authentic carvings to put on it,” Ford goes on. “So we came up with the idea of telling the story of The Magician’s Nephew in the carvings. We used nine images from the book that are carved into the panels of the wardrobe, plus the lion’s heads at the top. At the bottom, we’ve got the White Witch and her sister. So the whole of the wardrobe tells quite a nice story.”

The Snowy Forests of Narnia

To further transform soundstages into the winter-cursed Narnian forest, Ford secured the talents of two Kiwi movie veterans — Russell Hoffman, the head greensman who led a team of arborists and landscapers to create the forest of Narnia, and “snowman” Peter Cleveland, whose crew used eleven different materials to create the copious make-believe snow that adorns so many of the Narnian sets.

Hoffman’s indoor landscapers planted over 225 trees on the production’s soundstages to match the forests of Eastern Europe. “I’m actually a staunch environmentalist,” Hoffmann notes, “so the trees that we chose were all part of experimental crops that have been used for commercial purposes. They’re not part of the New Zealand ecology or anything like that.” While Hoffman’s lumberjacks trucked the trees far-and-wide from around the country’s north island, Cleveland reached out to the U.K. and the U.S. for two different types of artificial snow used to create Narnia’s winter wonderland.

“We used air foam on the trees, which is the same material used in the construction industry to insulate houses,” Cleveland explains. “Another type of product we used is a paper snow which comes from chopped up diapers. These were from Welsh diapers, and the foam product on the trees came from Tennessee. The bonus of that paper product was that we could eliminate footprints easily and return the set back to a smooth dressing for each new take.”

The Beaver Lodge

Another of Ford’s remarkable designs is the “beaver lodge,” where Mr. and Mrs. Beaver give the Pevensie children refuge while reciting the history of Narnia. Director Adamson envisioned the beavers as rustic craftsmen, creating their home, furniture and tools from their surroundings, and trading with the local dwarves for other commodities. He wanted a very authentic, “beaverized” look, which required the designers to unexpectedly immerse themselves in beaver biology… and architecture.

Says Jules Cook, one of Ford’s key art directors who supervised the lodge set: “Much of the inspiration for the beavers’ environment, both in the interior, shot on a soundstage at the Henderson Studios, and the exterior, filmed as part of a vast snowscape at Kelly Park, was taken from watching beavers in their natural habitat in the 1988 IMAX film ‘Beavers.’ In a climactic scene in that film, a bear tears apart a beaver dam, and close examination of the destruction provided a strong basis for the scene in our film where a pack of the White Witch’s wolves tears through the lodge looking for the Pevensies.”

“Beaver dams generally let part of their river’s water through the structure,” Cook further explains, “and particular attention had to be paid to how a flow of water would freeze around the habitat.” Chainsaws and Arbortec drill attachments were used to create a unique ‘chewing’ effect on the logs, and as beavers tend to strip the bark off branches, this was done as well. Set builder Pete MacKinnon estimates that he used over 4500 sticks, all “between finger thickness and leg thickness,” to create the set. The lodge’s furniture is appropriately makeshift, with the Beavers’ living area cluttered with miniature tools, fishing rods and collectibles, while Mrs. Beaver’s “homey” touch is responsible for the spun textiles and homemade preserves. In a subtle flourish, Anglophiles may note Mr. Beaver’s collection of Toby jugs, a series of beer mugs dating back to the 18th century, usually depicting various human characters. Of course, the careful eye may note an important difference — Mr. Beaver’s Toby jugs are beavers as well!

The White Witch’s World

Also forged at Henderson Studios were some of the film’s most imaginative and striking sets – those that make up the White Witch’s world, including Great Ice Hall, the Witch’s dungeon, and the Witch’s courtyard, each constructed to reflect a hauntingly glassy realm of snow an dice. The production used more than 7,000 gallons of resin and half a kilometer of fiberglass in the creation of this frozen-over world.

In the White Witches’ courtyard stand dozens of Narnian creatures – including griffins, bears, centaurs, panthers, giants and fauns — each frozen into stone statues by the Witch. To create this eerie, accursed sculpture garden, Ford and Gracie had their teams hand-sculpt some 70 full-scale, life-size statues from Styrofoam molds designed by a team of ten global artists (from places including Beijing, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand) over a five-month period under the supervision of veteran Aussie movie craftsman John Searle (“Moulin Rouge,” “Babe”).

“We started by using a technique we hadn’t tried before, using a computer to carve out all the profiles of these huge carvings,” Searle explains. “We then had each statue’s profile cut out of foam, generally twenty-five or fifty millimeter sheets of polystyrene glued together. From there, a sculptor carved them down to form, using sharp knives, sand paper and abrasives. We then had to cut the statue open and fill it with steel armature, so it could be screwed into the ground. But that was just the first phase! Then we had to coat each one to give it a finish that made it look real. For instance, the bear has a different texture from a lion. With the mythological creatures, a lot of them have armor, which was made by WETA, so we applied all those pieces as well. Finally, we gave it a seal coat of a urethane, then at last, it was onto the painters. It was quite a process.”

The Queen’s Castle

Finally, the filmmakers turned to the creation of the queen’s castle, another major challenge to their creativity. “The queen’s castle in the book is not described as being made of ice,” Ford notes. “We made a very rash decision early on that we would make our castle out of ice. That all seemed very exciting at the time but then of course, came the problem for me of how to build a castle out of ice.”

“We built these mammoth sets out of half-inch thick fiberglass,” Ford describes. “Every piece had to be carved out of polystyrene. Then the polystyrene had to be covered in a layer of impermeable plastic, almost like Glad Wrap, so that the fiberglass didn’t stick to it. Each piece was then fiberglassed with a gun, using fiberglass with color mixed in it, so we get this very slight blue look to it. Finally, we did a lot of research with Don McAlpine on the lighting. He did a fantastic job making this stuff look exactly like ice.”

Though much of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe was spun out of whole cloth on soundstages, a number of authentic locations were also utilized. The production spanned the globe, shooting in Poland, the Czech Republic, England and of course New Zealand – as well as the one place that has come to truly represent fairy-tale worlds: Andrew Adamson’s native New Zealand. After scouring the world for forests as lush and hills as green, Adamson ultimately chose New Zealand’s South Island to shoot the climactic battle for Narnia as Aslan’s army, now led by Peter, takes on the witch’s forces. He chose a location known as Flock Hill, because, he says, “it’s the most amazing place I’ve ever seen.” The company also used Elephant Rocks, a steep valley containing hundreds of unique rock formations popular with climbers, to film crucial scenes in Aslan’s camp; and filmed the exteriors of Prof. Kirke’s mansion at Auckland’s Monte Cecilia Park, a Catholic refuge founded in 1913.

For the cast, New Zealand offered an ineffable sense of magic that further inspired them. “New Zealand was like entering Narnia,” says Tilda Swinton. “It was like walking into a storybook that was published in the ’30s. There’s something very spiritually about that land, with its huge sky, extraordinary mountains, and this sense of peace,. We were really fortunate to just spend time there.”

The Narnians Come to Life: The Work of WETA Workshop

“One of the most inspiring things in out journey into Narnia was to work alongside such a remarkable artist, storyteller and visual persona as Andrew Adamson. The opportunity to raise our craft over and above what we did on `Lord Of The Rings,’ to bring it to bear on such a diversity of design and culture, has been a dream come true.” — Richard Taylor, WETA Workshop

Who do you go to create an entire world populated by wildly imaginary creatures? One place has become legendary for their nearly magical skills in this department: Richard Taylor’s WETA Workshop, the collective group of artists based in Wellington, New Zealand, who designed and created the visual and makeup effects for all three chapters of Peter Jackson’s landmark “Lord of the Rings” trilogy. Adamson knew he needed WETA on his side in helping Narnia’s creatures and all their battle accoutrements – weapons, armor, etc – become reality.

Taylor, a four-time Academy Award winner, was thrilled to enter another beloved fantasy universe, one that held out its own entirely unique challenges. “C.S. Lewis conceived of Narnia as a world of a child’s dreams, where all mythologies come together. This gave us wonderful opportunities to design harpies, minotaurs, centaurs, and goblins, all interacting in the same fantastical world,” he says. “We also created dozens of species never before seen on the screen.”

While WETA conceived some ten species of creatures for Peter Jackson’s “Lord of the Rings” trilogy, for The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe they bring to life a remarkable 60 different species of creatures, of which nearly half do not normally occur in nature. The WETA artists quickly became aware that while Tolkien and Lewis are often compared, the imaginary worlds they created were entirely different in style and texture. Due to Lewis’ less detailed description, for Narnia, they had far freer reign.

“In the case of Narnia, you’re entering through the back of the wardrobe, into a kind of dream universe, into this much more fancy, enriched world,” elaborates Taylor. “Therefore, there wasn’t the same strict brief for us to hang our design on. We realized, thankfully, that we were able to bridge out at a much greater extent into fantasy, drawing on the rich mythology that C.S. Lewis’ writings took on. It gave us a broader and richer palette of design than we had on `Lord of the Rings.’ The many visual techniques we used combine to create a fully-realized fantasy world the likes of which has never been seen on film. The craftspeople and technicians have pushed a new extreme of artistry in their pursuit to bring Narnia to the screen, which we hope will inspire a whole generation, young and old, to dream for themselves.”

One of WETA’s most complicated creations for the film were the centaurs, the half-man, half-horse species – borne out of Greek mythology — which required human actors to wear animatronic horse bodies co-designed by Taylor’s artisans and K.N.B’.s Howard Berger. “The centaurs were one of our more complicated characters,” Berger comments. “Richard Taylor and myself had previously done centaurs for ‘Hercules’ and ‘Xena,’ but we wanted to make these far better.”

Another challenge for WETA was the film’s climactic battle, for which WETA Workshop complemented costumer Isis Mussenden’s battle gear wardrobe with a spectacular array of more than 1300 weapons, including swords, maces, shields etc. and armor (150 metal and leather chest plates, patented, handmade chain mail). The magic was in the details. “It’s the final touches that will make it feel like these were all made by craftsmen of Narnia,” Taylor notes. “We all hope that we played a small part in creating a world that feels cohesive and real and alive for audiences to enjoy.”

Working closely with both WETA and Adamson throughout was Howard Berger and his K.N.B. team who make magic out of prosthetics, masks and bodysuits. Berger, who approached the filmmakers early on fired up to work on the project, was completely in tune with Andrew Adamson’s quest for realism in creating this fantasy world. “I approached it from the start as if these we were creating living creatures, bringing them to life with the help of the actor. Ultimately, I think we were responsible for twenty-three individual species. We created a hundred and seventy individual characters for the film, and shot 150 days with them in New Zealand and Prague,” sums up Berger.

During his six-month prep on the film back in Los Angeles, Berger employed over 100 makeup artists, technicians, fabricators, mold-makers, painters and mechanics. “We recruited the best we have in the makeup business,” he says. “I asked everybody to read the books so that they understood that this was not just a movie. I wanted them to understand the essence of why this film was so important to me. When I talked about Mr. Tumnus, or Ginarrbrik, or the White Witch, everybody knew what I was talking about and what they should be like so we were all on the same page. We all felt like this was a journey unlike any other movie we had done before.”

Among Berger’s favorite creations is the minotaur Otmin, which he calls “the coolest monster K.N.B. has ever made.” Using a radio-controlled animatronic head and requiring multiple puppeteers to operate, Otmin has a personality all his own. “As far as bad guys go, he’s a combination of some of my favorite creatures, a mix of a `Where the Wild Things Are’ creature with a primate. He’s very real.”

Otmin also required one of the most detailed body suits ever made. “It’s a fabricated muscle suit, so it has muscles, fat and even veins, clear plastic tubing that’s been stitched in a pattern,” Berger explains. “The fat is basically water-filled bladders so that his chest and arms jiggle. His biceps also contract. And, once that structure was built, the fabrication department put a spandex skin that’s sewn onto the muscle suit. It was then painted, and all the hair was hand-tied individually. Otmin’s remote-controlled head has lips and jaws that move to mimic dialogue, eyes that blink, moving ears, all the bells and whistles. Coupled with the muscle body suit, it added sixty pounds to the actor’s frame. And it took about 45 minutes just to put the suit on.”

Says Shane Rangi, the actor who plays Otmin and wore the carefully engineered suit: “The suit was dark and extremely hot and I was 100% blind. There were 27 servos in there going off, so it was also fairly noisy. I couldn’t really hear a lot. The trick then to working? Not to be claustrophobic! ”

Rangi, along with James McAvoy and some 200 extras doubling for fauns, centaurs and the like also had to wear spandex pants dyed in a green screen hue. This would allow for the next key step in the process of brining their characters to life: allowing VFX supervisor Wright and his artists to superimpose the legs of a goat, ram, bull or horse to the humans playing these mythological creatures who populate Narnia.

Behind Narnia’s Magic: The Special Visual Effects

“We had gigantic challenges along the way. The battle alone was made up of thousands and thousands of creatures, which includes polar bears, lions, tigers, centaurs, ogres, boggles, etcetera. Just an incredible undertaking.” — Producer Mark Johnson

The creation of Narnia would ultimately require more than just creative power – it also required massive computing power, combining the efforts of the some of the hottest and most innovative effects houses in the world to digitally enhance the otherworldly characters and landscapes of this alternate universe.

“This is a story filled with incredible creatures,” remarks Adamson. “To give a sense of the scope, in the final battle, there are 20,000 creatures. All these creatures were created at least partly in a computer but no singular approach was used. Some creatures are CG all of the time. Some creatures are half computer generated and half live-action. A centaur, for instance, might have a human upper body with a computer generated horse lower body, while the beavers were entirely computer generated. The idea was to have it all meld together into one cohesive universe that feels entirely real.”

“The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe is one of the biggest special effects movies ever made,” adds producer Mark Johnson, “and to pull it off we used three of the biggest, most creative effects companies in the world — Rhythm & Hues, Sony Pictures Imageworks and ILM – simultaneously.”

In the beginning, the filmmakers asked several effects companies to “audition” for the various characters, almost like actors. Johnson explains: “We would take a single character, let’s say Mr. Beaver, and ask five separate companies to take a stab at animating this character. There were no guidelines. We said `let’s see what you can do to demonstrate what Mr. Beaver would look like.’ That’s how we chose the best houses for the job.”

Overseeing the work was VFX Supervisor Dean Wright, a veteran of the second and third “Lord of the Rings” films. Wright collaborated with Rhythm & Hues Bill Westenhofer, Sony’s Jim Berney and ILM’s Scott Farrar to create somewhere between 1,000 and 1,400 CGI shots and images for the film. According to director Adamson, “there really isn’t one frame, one scene, that is not touched by a visual effect.” Eventually, some 1,000 people would work on the effects and some 50 terabytes of information for the film would be stored at three different effects houses. Large libraries of newly created images were shared back and forth by each of the houses as they worked in concert with one another, layering scenes with richer and richer effects.

So while Sony Pictures Imageworks was creating the CGI beaver performances and forging CGI wolves so photo-realistic they were able to mix seamlessly in with a pack of real animals in certain sequences, Rhythm & Hues was honing Aslan’s magnificent musculature and ILM was tinkering with how centaurs might walk. Then, the teams might switch, each working on a different aspect of Narnia’s massive world. “In every element, the aim was always to have each the creatures be entirely believable right next to our human cast,” sums up Wright.

Ultimately, all the film’s elements – from locations and designs to practical effects and digital wizardry would come together in the most challenging sequence of all: the climactic battle for Narnia as Aslan’s army takes on the forces of the White Witch. Andrew Adamson had envisioned a spectacular scene involving some 20,000 characters on screen at once – one that sprung primarily from his imagination. “In the book, the battle is one about a page and half long. Lewis writes about it in very simple, `you should have been there’ terms, but in my imagination was always this incredible battle with minotaurs against centaurs against fauns and satyrs. We had to show the battle, an incredible battle like nothing that has ever been done before,” says the director.

The sequence was shot at New Zealand’s Flock Hill Station, on a rugged plateau featuring snow-capped vistas. There, the film’s cast and hundreds of extras dressed in the otherworldly creations of WETA and K.N.B., played out the war for Narnia’s future. Later, Rhythm & Hues employed the same groundbreaking software used to create the spectacular battles in “Lord of the Rings’ – the artificial intelligence program known as Massive – to multiply the fighters into the tens of thousands and to control each fighter’s individual moves and motions. “We have 20-30 creatures on screen at any one time and they each have their own unique attributes in terms of how they jump, run, walk, move and fight,” observes Dean Wright. “It’s an enormous challenge to make this look believable, but with the computer simulations, you have the tools you need to make it look as good as it possibly can.”

When the battle was completed, Andrew Adamson knew his Narnia had truly made the journey from a fantastical vision in a child’s fevered imagination to the motion picture screen. “Making this film was a daunting exercise in every way,” sums up Adamson. “It was very technically daunting in terms of effects and digital creations and daunting from a filmmaking perspective in terms of scope and design. It was daunting to work with four children as the main characters. But, I think the most daunting thing of all for me was simply the responsibility I felt to this beloved story. It’s a huge thing to try to live up to what millions of people have imagined and dreamed about Narnia over 3 or 4 generations but that is what we set out to do.”

These production notes provided by Walt Disney Pictures.

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe

Starring: Georgie Henley, Skandar Keynes, Anna Popplewell, William Moseley, Jim Broadbent, Tilda Swinton, Rupert Everett

Directed by: Andrew Adamson

Screenplay by: Ann Peacock

Release: December 9th, 2005

MPAA Rating: PG for battle sequences, frightening moments.

Studio: Walt Disney Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $291,710,957 (39.2%)

Foreign: $453,300,315 (60.8%)

Total: $745,011,272 (Worldwide)