Tagline: The world was watching in 1972 as 11 Israeli athletes were murdered at the Munich Olympics. This is the story of what happened next.

In September of 1972 an unprecedented terrorist attack unfolded live before 900 million television viewers across the globe and ushered in a brave new world of unpredictable violence.

It was the second week of the Summer Olympics, and in Munich, West Germany, the games that had been dubbed “The Olympics of Peace and Joy” were off to a rousing start with swimmer Mark Spitz and gymnast Olga Korbut wowing the crowds.

Suddenly, without warning, an extremist Palestinian group known as Black September invaded the Olympic Village, killing two members of the Israeli Olympic team and capturing nine as hostages.

The tense stand-off and tragic massacre that ensued played out with stunning immediacy on television before an international populace and ended 21 hours later when anchorman Jim McKay spoke the haunting words, “They’re all gone.” While the Munich terror was seen and felt around the world, the intensely secret aftermath of the event has remained largely unknown.

Now, from director Steven Spielberg comes Munich, a gripping thriller based on the events of Munich 1972 and the highly charged mission of retribution that followed-by the covert hit squad known to Israeli intelligence as “Operation Wrath of God,” one of the boldest and most aggressive assassination plots in modern history. In taut, vivid and human detail, the film takes audiences into a hidden moment in history that resonates with many of the same emotions in our lives today.

At the center of the story is the young Israeli patriot and intelligence officer Avner (Eric Bana). Still mourning the Munich massacre and infuriated by its savagery, Avner is approached by a Mossad officer named Ephraim (Geoffrey Rush) who presents him with an unprecedented mission in Israeli history. He asks Avner to leave behind his pregnant wife, relinquish his identity and go completely underground on a mission to hunt down and kill the 11 men accused by Israeli intelligence of masterminding the murders at Munich.

Despite his youth and inexperience, Avner soon becomes the leader of a team of four very diverse yet highly skilled recruits: the brash, tough, South African-born getaway driver, Steve (Daniel Craig); the German Jew Hans (Hanns Zischler), who has a flair for forging documents; the Belgian toymaker-turned-explosives-expert, Robert (Mathieu Kassovitz); and the quiet, methodical Carl (Ciaran Hinds), whose job is to “clean up” after the others.

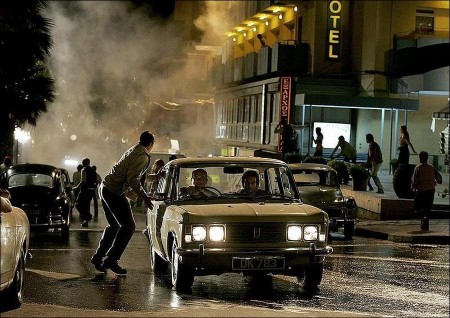

From Geneva to Frankfurt, Rome, Paris, Cyprus, London and Beirut, Avner and his team circle the globe under a cloak of extreme secrecy, tracking down each man on a closely guarded list of targets and carrying out intricately plotted assassinations, one by one. Working outside the rubric of international law, adrift without home or family, their only connection to humanity becomes one another. But even that starts to fray as the four men begin to argue among themselves about the unsettling questions that just won’t go away: “Who exactly are we killing? Can it be justified? Will it stop the terror?

Torn between their desire for justice and their own growing doubts, the mission begins to tear at the souls of Avner and his team, and it becomes increasingly clear that the longer they remain on the hunt, the more they are in danger of becoming the hunted.

Revisiting Munich

“Our worst fears have been realized tonight.” With those words, uttered on September 6, 1972, television announcer Jim McKay brought the overwhelming news that the 11 Israeli athletes, coaches and sporting officials taken hostage by Palestinian kidnappers in the Olympic Village at Munich were all dead, most of them killed on the tarmac of Furstenfeldbruck Airport on the outskirts of Munich in the midst of the German authorities’ final botched rescue attempt. A shock wave rippled across a world already engulfed by conflict. With turmoil raging in Vietnam, Northern Ireland and the Middle East, not to mention protest and unrest in the streets of America and Europe, these Olympics had been seen as a much-needed reminder of global unity and a brief oasis of peace.

But it was not to be. The world soon learned that the men who had broken into the Olympic Village wearing tracksuits, armed with Kaleshnikov rifles and bearing hand grenades were Palestinian fedayeen (literally “men of sacrifice”). Many of them had been recruited from refugee camps in Jordan, Syria and Lebanon; their aim was to bring the Palestinian cause to worldwide attention and exchange their hostages for the release of 234 Palestinian prisoners, as well as the notorious German terrorist leaders Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof.

From the beginning, the staunch Israeli government of Golda Meir refused any negotiations, and Germany refused to allow an Israeli special-forces team to operate in Munich. Instead, the German police launched their own series of ill-fated hostage rescues. It began pre-dawn on September 5 and continued for 21 hours-involving aborted plans and ultimately resulting in a chaotic shoot-out in which hostages, five of their kidnappers and a German police officer died. German police took remaining three kidnappers alive. Weeks later, in what many believe was a staged event based upon a deal struck between the Palestinians and the German government, the three surviving fedayeen would be released from German prison when hijackers of a Lufthansa plane demanded their release.

The Olympic games continued after a memorial service, despite the somber, stricken mood. In the media and around the world, there was an attempt to return to some pretense of normalcy.

What happened next never made the evening news. Publicly, Israel responded to the terrorist act on September 9 when its Air Force bombed PLO bases in Syria and Lebanon. At the same time, Prime Minister Golda Meir and the Israeli cabinet’s top-secret “Committee X” authorized another mission that would never be spoken about. They devised a deep undercover effort designed to strike fear into the hearts of all terrorists threatening Israel-the elimination of 11 suspected Black September operatives by any means necessary.

This was “Operation Wrath of God,” the still controversial and heavily debated targeted assassination program that, according to several published sources, would ultimately kill at least 13 men without prosecution or trial. The international team of anonymous, but skilled, assassins that Israel created came to have a resounding impact that continues to echo today. Though neither the Israeli government nor the Israeli secret intelligence agency-the Mossad-have ever officially acknowledged the existence of these hit squads, a number of books and documentaries utilizing inside sources have since provided details of how and why “Wrath of God” carried out its aims. Two Israeli generals have also publicly confirmed that the targeted assassination squads did indeed exist: General Aharon Yariv in a 1993 BBC documentary and General Zvi Zamir in a 2001 60 Minutes interview.

For film producer Barry Mendel, the events of Munich 1972 were always a vivid, harrowing memory-and the more he learned about them, the more they haunted him, which is why he began to envision a thought-provoking suspense thriller about the most unknown and contentious part of the unforgettable story. Mendel has strong recollections of the tragic day it all started and the feeling that something in the world had changed for all time.

“I remember Mark Spitz winning all those medals, and the next morning we woke up, turned on the Olympics, and there was Jim McKay telling everyone what had happened,” recalls Mendel. “And that was it. My whole family was suddenly riveted to the TV. We spent the whole day together watching the events unfold, and it was something I knew the world would never forget.”

Mendel developed the project for four years. Kathleen Kennedy heard about the project from Mendel, with whom she had previously worked on the innovative mystery-thriller The Sixth Sense. She, in turn, brought the story to director Steven Spielberg, who finally decided to go forward with the project on the heels of his apocalyptic blockbuster War of the Worlds, based on H.G. Wells’ classic science fiction novel.

Kennedy felt the story was an ideal match for Spielberg’s eclectic, but always keenly focused, storytelling sensibilities from the minute she heard the idea. “Steven has the facility to be such a great storyteller, and with a piece of material like this and a subject matter that carries so much importance, I became very excited by the possibilities,” she says. “I couldn’t think of anybody better suited to this story.”

Kennedy continues, “Today, we’re bombarded with so much information and there are so many events happening on a daily basis, I think that to really go back in history and get perspective is something that storytellers and filmmakers can do-in order to make sure that we don’t forget where we have been. I think that’s an important reason why Steven decided to do this movie. It’s an event that sheds light on a lot of current events and it allows us to step back and ask what happened 33 years ago and what did we learn from it? At the same time, it is an edge-of-your-seat thriller that would be compelling, even it weren’t based on truth.”

Spielberg has previously explored resonant moments in history with such epic films as Empire of the Sun, Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan. The story of Munich also seemed to raise imminently vital questions about the world in 2005 and beyond, which is partly what drew Spielberg to explore the 33-year-old event in more human detail than previously seen.

Spielberg has his own intense memories of 1972. “I remember exactly where I was, the television set I was watching it on, and how I was watching-like everybody else, Wide World of Sports, when this incident took place,” he says. “It made an indelible impression on me, and I think that impression was redoubled years later when I saw the documentary One Day in September.”

The director’s immediate way into the story lay in the realms of suspense and human emotion. Spielberg became intrigued by a question that had never been publicly addressed: How did this covert mission affect the men assigned to carry it out? To explore that question, Spielberg and Kennedy brought in Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Tony Kushner to work on the screenplay after Eric Roth (Forrest Gump, The Insider) wrote a draft inspired by the book Vengeance by Canadian journalist George Jonas.

Kushner’s internationally lauded play Angels in America had brought forth a multi-layered examination of the social, political, sexual, racial and religious questions facing the nation at the end of the 20th century, but he had never written a screenplay. Kushner met with Kathleen Kennedy and was intrigued by the probing concept for Munich she presented to him. “I saw that what they were proposing was a very murky, problematic and complicated story not about the massacre itself, but about the aftermath and about the policy of targeted assassination, and I became very interested,” he recalls.

At first Kushner simply wrote notes for Spielberg on the existing screenplay, declining to try his hand at a feature film. Spielberg relentlessly pursued him, however, and Kushner accepted the challenge.

For Spielberg, Kushner’s participation was key. “I wasn’t really sure I was going to make Munich until I began reading Tony’s words, and then everything immediately coalesced for me,” says the director. Adds Kennedy, “I think Steven felt he was now in a creative partnership with someone who really understood the complexity of these issues. He knew he was on the way to having a screenplay he would feel comfortable shooting.”

Kushner distinctly recalls his own experience of the 1972 Olympics, a memory he drew upon as he began his exploration. “It was a transformative moment,” he says. “I was 17 years old and it was a very stark thing for me and my family. It was heartbreaking, devastating. I remember a lot of anger in America and especially a great deal of rage that the situation had been blown so badly.”

Yet Kushner hoped to approach the story with as blank a slate as possible, coming at it without any singular point of view and aiming more at baring provocative questions than providing any pretense of black-and-white answers. “It’s a story filled with paradoxes and contradictions,” he notes. “It’s also a story about a covert operation, so nothing is entirely known for sure and most likely nothing ever will be. So, we gave ourselves some permission to invent and to deal with these characters on a more human level. I feel we have created a very scrupulous piece of what I would call `historical fiction.’”

Forging these characters on a deeper, more humanized level brought a myriad of challenges. “I always like to do difficult things,” admits Kushner. “And the big difficulty of writing this story-as was made clear from the beginning-is that our main dramatic agents, our protagonists, are five guys who are assassinating people. They had to be plausible as secret agents, not in the James Bond sense, but in the sense of real field operatives working for an intelligence agency-and at the same time, there is this question of, `Who are these guys really?’ So what was fascinating for me was calibrating these characters, especially Avner.”

He continues, “Avner is the leader of the group, although not in any conventional sense. But how does his conscience become unsettled? How does this sort of intersection of his own internal ethics and his sense of survival come into play? It became more and more the story of a man whose decency just won’t let him off the hook.”

For a long time, the project remained untitled, but as Kushner wrote, he became enamored with Munich, which also struck Spielberg as taking precisely the right understated tone for a film that presents a singular event that evolves into a persistent moral conundrum.

“I like the simplicity of it because I think this is a film that starts with a stark, historical fact and then it shows that there’s nothing simple about it at all and that all the certainties that might seem to surround it can also be questioned,” Kushner explains. “There’s also an immense resonance to the name Munich. It’s the birthplace of Nazism and of the Munich of 1972, all at once. It has a kind of iron ring that seems appropriate to the relevance of the story.”

Even with all the intense collaboration on the screenplay, Kushner was excited to see where Spielberg would take the story once the cameras were rolling. “No one does suspense better than Steven,” he comments. “In all of his films you know you will be put directly in the middle of what’s happening. The interesting thing is that inside this suspense thriller, you also get pulled intellectually into questions that lead into even more questions. I think he found a way to blend an amalgam of various forms that will make for a very interesting film.”

Spielberg’s vision and confidence, borne out of a combination of his love for cinema and his years of experience, allowed him to direct Munich with a somewhat different approach from his other films. While he had a definitively clear vision of the story, there were no storyboards on this film. He worked in an acutely spontaneous and organic manner, intuiting the needs of each scene as they unfolded before him.

The experience on set, therefore, was deeply collaborative for both cast and crew. Summarizes Daniel Craig, who plays one of the hit men, “Steven was absolutely fluid in his directing style. He would see something happening and immediately try to take advantage of it-which is a very exciting way to work. It’s also very scary. But if you’re going to be in that situation, it’s good to be doing it with Steven Spielberg, because he brings such a wealth of knowledge about every aspect of cinema to the process.”

Casting Munich: A Global Cadre of 200 Actors Joins the Production

The making of Munich began with an exhaustive international search for actors to play the nearly 200 parts in the intricate screenplay, parts ranging from famous political figures to covert agents who work in the shadows. Armed with only a general description of the film’s story and the promise of working with Steven Spielberg, casting director Jina Jay traveled the globe looking for fresh and interesting faces. Throughout her search, the focus was on carving out viscerally real characters, rather than relying on star power to drive the film’s story.

Explains Spielberg, “There are more speaking parts in this film than any I’ve ever directed, including Catch Me If You Can. Having this many characters in a multi-layered story that spans a couple of years and numerous countries, it was very important to me that even the smallest character be as interesting as the most central character. This story portrays a very painful and tragic part of our collective history, and I wanted to have an amazing ensemble to tell it.”

“We were helped and facilitated by wonderful casting contacts all over the world,” says casting director Jay, whose work would ultimately bring together actors from such diverse places as Algeria, Egypt, Greece, Iraq, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Syria, Tunisia, Yemen, Albania, Austria, France, Germany, Poland, Romania, Spain, Sweden, the U.K., the U.S., Canada and Japan, as well as local actors from both Malta and Hungary, where the film was primarily shot.

The core of the casting lay in finding the hit squad itself-the five utterly diverse men who, in the wake of the hostage massacre at the 1972 Olympics, agree to upend their personal lives, give up their former identities and take on an unimaginably perilous undercover mission on behalf of Israel.

Spielberg had a very complete vision of what he was looking for in each of them. “I felt it was very important not just to find different looks for each of the five men, but also to find five different acting styles, five different accents, five very unique personalities,” says the director.

The unlikely leader of the group, Avner, is also its youngest member and the only native Israeli. Avner is intensely devoted to his country, but has never had to kill someone before this mission. To play Avner, Spielberg always had in mind Eric Bana, whom he had seen in Ang Lee’s adaptation of The Hulk. “When I saw him in The Hulk, I saw a warmth and a strength and even a little trickle of fear behind his eyes, which I think makes him very human. I was very determined that I was going to humanize the character of Avner in this story, so Eric was my first choice from the outset,” states Spielberg.

Bana was in Los Angeles finishing his role in Troy in fall 2003 when he got the call saying that Steven Spielberg would like to see him. After meeting Spielberg on the cavernous set of The Terminal, Bana was taken aback to learn that Spielberg wanted him to take the lead role in an intense thriller about the highly controversial Israeli hit squads. “I was shocked and surprised and thrilled and scared, of course,” says Bana.

Even though he was born and raised in Australia, like many of the cast and crew Bana had his own very personal recollections of the Munich Olympics. He notes, “I was only four or five at the time, but I always remembered some of the images, and it was a story that became very familiar to me through the years. It’s an event that keeps coming back at you, because it still seems so current.”

Bana began to research the role intensively, reading not only about the incident in Munich and life as a Mossad agent, but also the complex history of the Middle East conflict. As he did so, he became intrigued by Avner’s personal crisis as the mission begins to shake his very foundations. “Avner goes through a real evolution,” Bana observes. “He starts out as someone who is obviously very angry about what occurred in Munich. Then he becomes a young man who is given a truly overwhelming task and has to learn very quickly how to lead. He initially questions what the team is doing, but then something interesting happens: he hardens. As the rest of the group is softening in their resolve, we see Avner do the opposite. But by the end of the movie, we see him becoming more and more torn about the journey he’s been on and what he’s allowed himself to become.”

Bana enjoyed the close friendships that developed on the set between the five actors playing the members of the assassination squad. The five stars, each hailing from different countries and backgrounds, arrived together early in Malta and soon formed a tight-knit connection that surprised even them. “I hope that unique camaraderie really comes across, because it was 100 percent genuine,” Bana says. “We all came from different parts of the world and had very different points of view and we’d get into all kinds of amazing discussions, but we also really respected one another. It was really cool to experience this.”

British actor Daniel Craig-who recently made global headlines when he was announced as the fresh new face of the legendary Agent 007, James Bond-joined the cast as Steve, the South African-born recruit who appears to be the group’s toughest, bravest and most unwavering member.

“Steve is a character who, on face value, seems to be very strong and very in control of his destiny,” says Craig. “Like all the guys, he believes in this job because he believes in Israel. He believes some action has to be taken because of this terrible act at Munich. And he’s someone who has always dealt with life like a bull in a china shop-he just dives in headfirst and deals with the consequences later. So Steve at first is very gung ho, but as the movie goes on, he suffers because of the terrible acts that they commit. And that’s what interested me so much about doing the film; he’s a flawed character, and he doesn’t expect to feel the emotional turmoil he starts feeling.”

Craig was too young to remember watching the 1972 Olympics, but he has been aware of the events that took place there for a long time. “I think the repercussions of that time have really molded all of our lives,” he says. “It was a kind of worldwide end of innocence-and we’re still dealing with the consequences of that. It’s one of the most significant events of the 20th century, and I think Munich finally puts a human face onto it.”

While Craig is an Englishman playing a South African, French actor and filmmaker Mathieu Kassovitz plays Robert, the Belgian member of the team. A talented toymaker, Robert is equally skilled at building deadly explosive devices. An accomplished director, Kassovitz had supposedly retired from acting, famously telling his agent not to call him about acting jobs unless it was for Spielberg. Now he had his chance, and once he saw the script, it was a done deal.

He comments, “I was blown away by the screenplay…by the structure of it, by the subtlety, by the intelligence, by the power and the guts. I think it’s a very smart movie about the concept of vengeance itself.”

Kassovitz was also intrigued by his character Robert’s unique journey as the most reluctant member of the assassination squad. “Robert is an interesting character, because like all the characters in the group, he is not a trained killer,” the actor explains. “He’s more somebody who is committed to the cause of Israel and therefore believes he is ready to fight for his land and his beliefs. He joined the army during the Six Day War, and because he’s a toymaker and very good with tiny mechanics, he became a bomb dismantler. But it isn’t easy for him.”

Indeed, Robert becomes more emotionally unhinged than the others by the brutal nature of the job facing them. “He is a little more sensitive,” Kassovitz observes. “He can’t always cope with the violence. Even if he’s part of the mission, there are things he can’t quite bring himself to do.”

Each squad member has his own series of dilemmas and internal divisions. Prolific German actor Hanns Zischler takes on the role of Hans, a transplanted German Jew who poses as a quiet antiques dealer, but is really a Mossad agent with a rare gift for forging documents. Playing a German Jew working for Israeli intelligence after the Munich incident was particularly interesting to Zischler-in all its emotional complications.

“Hans is probably someone who left Germany in the 1930s at the last possible moment with his family,” he comments. “He grew up in Israel, which was then Palestine, and was raised in both languages. I think he has this certain idea of being linked both to Israel and to Germany in a very strange way, which comes to the fore after these events. He is also a very pensive person. He has never really been an activist, so he feels he now has the chance to show his loyalty to Israel and his country through this service to the Mossad.”

Zischler was 25 in 1972 and has evocative memories of that powerful period in Germany. “It was a time when Germany was becoming more self-aware through this new generation that was coming of age. There was a sense that for the first time, people could really talk about the past as something that hadn’t been entirely resolved,” he recalls. “But the events at the Olympics were something different. That was something that came from the outside. It was like a meteorite hitting the country. We were all suddenly aware that this theatre of the Olympic Games had become a stage for a dark, horrible drama. And it all happened on television before the eyes of the world. For me, it was fascinating to have a chance to explore these events from a different angle in Munich.”

Rounding out the team of five is the meticulous, organized and cautious Carl, played by lauded Irish actor Ciaran Hinds. “Hans and Carl are a different generation from the other three,” observes Hinds. “These five guys are all very disparate, with different ages, different backgrounds, different upbringings. Some have been raised in Europe and some in Israel. And they’ve been purposely selected for their different qualities. Within this group, Carl is the one who wants to be absolutely specific that the targets are clean, that there’s no collateral damage, that nobody innocent gets hurt. He truly believes there is a right way to do the job, no matter how awful it is.”

Growing up in Belfast, where political turmoil was a constant, Hinds saw the events of the 1972 Olympics as part of an entire world in disarray. “I was quite sporty when I was young so I always watched the Olympics,” he says. “Due to what was happening in Northern Ireland, I was very aware of this kind of violence as a global thing. Because of this, the whole idea of Munich was very interesting to me. It has a way of looking at history that isn’t black and white. I think Steven presents a story that asks a lot of questions but doesn’t serve the answers up on a plate, and that is very important.”

The hit squad is only allowed official contact with their mysterious case officer Ephraim. To play Ephraim, the filmmakers chose Academy Award-winner Geoffrey Rush, the acclaimed Australian actor who came to the fore with his vivid portrayal of Australian pianist David Helfgott in Shine and has gone on to diverse roles ranging from the infamous libertine the Marquis de Sade to comic genius Peter Sellers. The role of Ephraim was something quite different again for Rush, which he discovered while reading the screenplay.

“Tony Kushner is a great dramatist and he has focused in on the very complex workings of what makes this story such a significant piece of history,” says Rush. “As you meet the character of Ephraim, you might think he’s just another fairly faceless bureaucrat, but in fact he becomes an unusual mentor to Avner as he goes through his very difficult trials as an assassin. Ephraim is like this ghostly figure that comes in out of nowhere to answer the big questions, whether moral or otherwise.”

The entire conception of the film was of great interest to Rush, who remembers watching the Munich massacre on television at age 21 in Australia. “I saw Munich as an international espionage thriller that is based on very real and very, very relevant events-and weaving through it all is a stimulating debate as these characters undergo a harrowing journey of self-revelation,” he comments.

Rush based his character’s accent and mannerisms on a composite of several historical figures. “I had our national broadcaster send me newsreel footage of Menachem Begin, just as a reference for the time and the culture,” says Rush, “because their storylines are similar, you know, moving from a politically radical background into a much more conservative governmental position.”

In further honing the character’s look, Spielberg said that he’d always thought of Rush as an Arthur Miller type of guy, and suggested that he pull his hair away from his forehead. In a conservative suit, bearing thick horn-rimmed eyeglasses and with his hair slicked back, Rush became Ephraim. He further worked on the character’s nuances with dialogue coach Barbara Berkery to find an accent that would best reflect Ephraim’s history. “I specifically wanted to meet somebody in their eighties who came from a Polish-Israeli background. I wanted to hear the distinctive patterns of that kind of voice,” says Rush. “So we went off, armed with a tape recorder like Colonel Pickering and Professor Higgins.” Rush found far more than he expected. “We ended up meeting people who were able to offer a tremendous amount of advice and anecdotes and history. I felt it was really my responsibility to enrich the character with as much cultural detail as I could.”

Then there is Papa, the shadowy Frenchman who buys and sells information to the team, and develops a paternal relationship with Avner that the young covert agent has yearned for all his life. Legendary French actor Michael Lonsdale, whose prolific film credits include the political thriller The Day of the Jackal, plays Papa. Lonsdale watched the events of Munich unfold in France where he says the nation was left in shock. When he heard that Steven Spielberg was making a film about the incident and its aftermath, he had no reservations about taking part in it. “It was a great pleasure and tremendous honor to work with Steven Spielberg,” he says. “Papa is not a large part, but I knew there was a lot that could be done with it.”

Also joining the global cast as the primary female character is Israeli actress Ayelet Zurer who plays Daphna, the young wife Avner must leave behind despite the fact that she is pregnant with their first child. During his secret mission, Daphna serves as Avner’s only solid connection to real life, and his unborn child remains his one link to his hopes for a better future. Zurer, who recently won Best Actress Awards from the Israeli Film Academy, the Jerusalem Film Festival and Haifa Critics for her performance in Savi Gabizon’s Nina’s Tragedies, was cast as the young mother-to-be only a month after giving birth to her own child, making her character’s emotional journey even more palpable.

“Daphna begins the film very naïve and happy,” says Zurer. “She thinks life is going to be just fine and the future looks great. She’s pregnant, obviously, which means new life. But then Avner goes away, and of course she knows he will be in a certain amount of danger, but I don’t think she really has any way of understanding what he is going through. When he comes back to her, he’s become this shell-shocked and broken man and it’s very painful for her to watch that, especially as he’s portrayed by Eric, who has a great deal of humanity in his face.”

Ultimately, Zurer sees the couple’s struggles as symbolic of something much larger. “They go through a really painful awakening, Avner and Daphna,” she notes. “I think they each in their own way represent somehow the loss of innocence of their nation and maybe the whole world.”

Says Barry Mendel of Zurer’s performance: “I think she is the heart and soul of the movie, because she so clearly represents the struggle between patriotism and family that Avner is facing. Ayelet has never been seen in a film outside Israel, and to find her was a great fortune for us.”

Whether they were veterans of the theater, national film stars, or it was their very first feature, every actor came to Munich in part for the chance to work with Steven Spielberg. The lure of working with the acclaimed director was strong enough to attract notable actors throughout the supporting cast, including Israeli actor Moshe Ivgy, who plays legendary Mossad agent Mike Harari, and Makram Khoury, who plays Wael Zwaiter, the cousin of Yassar Arafat who becomes the first target of Avner’s hit squad in Rome. Renowned Palestinian actress Hiam Abbass plays Marie-Claude Hamshari, whose husband is the squad’s target in Paris, and serves as a consultant and dialogue coach on the film.

One cast member had a particularly close relationship to the story-Guri Weinberg, an actor who is also the son of Moshe Weinberg, the Israeli wrestling referee and former champion wrestler who was killed in Munich when Guri was just one month old. Now 33, the same age as his father at the time of his death, Weinberg had the very rare opportunity to portray his father and pay tribute to him in Munich.

Weinberg found the experience of recreating the events that took his father’s life challenging almost beyond description, but also deeply therapeutic and meaningful. “The idea of actually walking through the footsteps of my dad and what he went through was so intriguing to me because when you hear the stories it is all about tidbits and it doesn’t all make sense as a whole. But when you walk through it like this, it makes everything real.”

He continues: “Portraying my father gave me a lot of respect for what he really experienced. It solidified my feelings and emotions, because I never had a relationship with him. So this finally gave me a relationship with him.”

Shooting Munich: Spielberg and Kaminski Update the Gritty ’70s Thriller

The story of Munich unfolds in three separate realms: the extremely public events of the Munich Olympics which took place under the glare of the international media, the extremely secretive and shadow-laden world of the Mossad and its unacknowledged hit squads operating around the world under an opaque cloak, and the internal worlds of the five diverse assassins themselves as they take on the psychological twists and turns of their unprecedented assignment.

To capture all of this visually, Steven Spielberg turned to one of his longtime trusted collaborators, the two-time Academy Award-winning cinematographer Janusz Kaminski, who has worked with Spielberg on nine previous films. A Polish teenager in 1972, Kaminski watched the events of Munich from a somewhat different perspective-through the veil of the Iron Curtain. “In Poland it was seen of course as a tragic event, as it was all over the world,” he says, “but the news that we got through official sources indicated a certain bias.”

Yet the cinematographer believes that one of the most fascinating elements of turning the events surrounding Munich into a motion picture is that nearly everybody has both a uniquely personal memory of it. “We all have our own experience with this event,” he says. “Even if you weren’t born yet, you’ve seen bits of it on television or in history books. Or you’ve been introduced to it through recent events. But whichever way you come at it, it is very relevant.”

Working in the usual manner of their unique collaboration, Kaminski’s initial action was to shoot a series of photographic tests to find a look that he and Spielberg felt suited the intense mood and suspenseful structure of the film-one that they hoped would echo some of the classic paranoid thrillers of the ’70s but with a contemporary edge.

“Steven and I are at a point in our relationship right now that we have to discuss things very little,” Kaminski notes. “He knows and trusts my judgment and I know his aesthetic sense very well. We converse a little, mostly about what we really shouldn’t do, but pretty much the visual style is left for me to determine. So I went to Paris in 2004 and started experimenting with various color schemes, various filters, various lenses, various lighting and various chemical processes.”

In further developing the film’s visual style, Kaminski looked at the story through the prism of a world map. “There are 8 different countries in the film, and I decided to give each a different look, very subtly, and each with a somewhat different color palette. This way each country has its own individuality, even though most of them were shot in Malta and Hungary,” he says. “So everything that happens in the Middle East is more colorful, warmer, sunnier. But once we leave that part of the world for Paris, Frankfurt, London and Rome the colors become cooler and more de-saturated. And even each of those European cities each have their own character and colors.”

For example, Kaminski points out that for the scenes in Cyprus he emphasizes more vibrant, sun-baked yellow tones, while in Athens the color palette veers towards Aegean blues, and then in Paris, the palette becomes much softer with an ambience of rainy skies. The lighting also shifts in the film, starting with a friendlier tone as the hit squad first gets to know one another at an intimate dinner and moving to a harsher photo-chemical process full of darker shadows that reflect the characters’ inner turmoil as their mission becomes more frightening and filled with doubts.

Each one of the assassinations is also shot in a unique manner, which is how Spielberg envisioned the film unfolding. “I wanted every assassination to be different, because as the team experiences each one, their views about what they’re doing change, the group dynamics shift, they change their feelings about themselves and each other, and there’s more and more stress, anxiety and pressure,” Spielberg explains. “So each of the missions has its own personal character.”

The choice of lenses was influenced by Spielberg’s desire to hearken back to a grittier, ’70s style of filmmaking. “Steven insisted, rightfully, that we use zoom lenses,” Kaminski notes. “He felt that ’70s cinema was so full of zooms that if you start zooming in and out you’re allowing the viewers to feel like they’re watching a film made in that time. It’s a very effective way of creating the sense of period.” Kaminski cites such realistic thrillers as The French Connection, Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor as inspirations for his work on Munich.

One of the biggest challenges for the cast and crew, including Kaminski, was re-creating the Olympic hostage situation with accuracy and riveting suspense. Scenes from the Munich Olympics open the film but are then revealed in much greater detail through flashback sequences that merge dramatic re-creations of the events with vintage documentary footage.

Spielberg felt that the flashback sequences would keep the emotional motivation behind all the events palpable throughout the film. “I felt there needed to be a constant reminder of what this story is hinging on, lest we forget what started this round of blood-for-blood,” he notes.

But shooting the re-creations was very emotional and wrenching. “You can imagine how difficult it was,” he says. “I hired Arab actors to play the Palestinians and Israelis to play Israelis… and they took it very much to heart. It was a very emotional catharsis and I wasn’t thinking so much of technique as I was about just holding this cast and crew together and keeping everybody on an even keel. It was a rugged couple of weeks.”

For the opening sequence, Kaminski focused on a searing, unadorned realism-“it’s a little bit flat, almost void of color,” he explains-but for the flashbacks he used a process known as “skip bleach” (most recently seen in the contemporary war film Jarhead) which gives a very harsh, grainy, color-saturated appearance to the scenes. “The flashbacks are darker, grainier, more foreboding. I wanted them to feel quite different from the present time,” the director of photography explains.

Comments Spielberg, “The bleach bypass is particularly effective in this film because it is inter-cut with the rosy grace notes of more standard lighting and set-ups. It tells you that you’re going somewhere else, inside Avner’s head and back into the past.”

When it came to the violence in the film, Kaminski understood that Spielberg did not want to hide the brutal nature of any of the events involved. “I think in this film, violence is purposely presented to the audience without any abstractions,” he says. “If you think of Saving Private Ryan, that movie was also extremely graphic but the audience realized it was there to convey the tragedy, the horror of those historical events.”

He continues: “I think this is a movie that tries to deal with a very serious subject in a mature and objective way. But it’s also a suspenseful movie, so that also created a very important need to stage the scenes in an unusual way. The way Steven created certain scenes was really amazing because he can convey suspense in just three shots. He uses zooms, he uses reflections, he uses extensive blocking, he uses cars wiping the frame revealing another portion of the scene. He’s a very skillful director when it comes to the camera.”

Kaminski also drew inspiration from his collaboration with the rest of the design team. “My work is always very much influenced by what the production designer creates and the wardrobe-and Rick Carter, with whom we’ve done many movies, is always great,” he summarizes.

Designing Munich: Bringing a Hidden World to Light

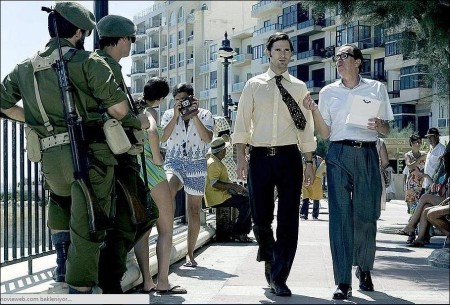

Munich takes place on a truly international scale, darting across 14 European and Middle Eastern countries in the course of the story, from Tel Aviv to Frankfurt, from Haifa to Paris, all during the early ’70s. Shot entirely on location, the film required the creation of more than 120 sets, so it was essential the filmmakers find a home base that could offer them a variety of looks and landscapes.

Spielberg and his Academy Award-nominated production designer Rick Carter found nearly everything they needed within the borders of two of the newest members of the European Union: the elegant Eastern European nation of Hungary and the Mediterranean island of Malta. Malta provided locations that could accurately double for all the Mediterranean and Middle East locales, while Hungary provided an ideal setting for the more than half a dozen different Northern European cities where the story of Avner and his covert assassination unit unravels.

A small island nation off the coast of Sicily, Malta stands at the crossroads between Southern Europe and Northern Africa, and despite its tiny size has found itself wrapped up in many grand historical events. From the wars of Rome to the battles of the Crusades to the Cold War, history has left its mark all over the island, making it an ideal resource and stand-in for multiple locales. For Munich, it was able to double for Israel, Cyprus, Lebanon, Greece, Italy, Palestine and Spain, with production designer Rick Carter building some 40 sets there.

“Malta has this kind of Mediterranean hodgepodge of culture where we could find areas that look like southern European locations in one spot and areas that look like Israel or Beirut in another,” Carter explains. “It actually gave us a way to visually divide the movie between the look of the hot, sunny, southern landscapes and the very different palette of the Northern European locations.”

Shooting in Malta began in Buggiba on the northeast coast. There, a small seaside café sported an Israeli flag underneath which extras dressed in the traditional garb of orthodox Jews crowded around a television set watching playback of the original 1972 Olympics newscast. From there the company moved around the corner to “the Olympic Hotel,” moving from Haifa to Cyprus within a few streets.

Many practical locations were utilized on the island: the historic 17th century Fort Riscoli and its barracks were transformed into a Palestinian refugee camp outside of Bethlehem; a square in the capital of Malta, Valetta, became the café in Rome where Andreas introduces Avner to Tony; a dry dock was dressed as the cosmopolitan 1970s Beirut; and private homes on the island doubled for seven different safe houses, as well as the home Avner shares with his wife Daphna, Avner’s father’s home, Golda Meir’s apartment and the villa in Spain where Avner and Steve look for Salameh.

Later, the production moved to Budapest, the beautiful, architecturally rich city on the river Danube. These environs provided Carter and his team with locations they could transform into a London street, a boulevard in Paris, a houseboat in Hoorn, a café in Rome and a small country shack in Belgium, to name but a few. While it takes hours to travel from Rome to Paris by car, Rick Carter was able to make a similar journey in only a few minutes in Budapest. “This one street in Budapest-Andrassy Boulevard, across from the Opera House- was the best Paris-looking location that we could find. What was interesting is that literally half a block away was the best Rome!” Carter muses.

Not only did the two countries provide a variety of landscapes, they also provided a window back into time. As Carter explains, “The story takes place in the ’70s, which was still the post-WWII era, when there was a lot more grime and grit on the streets of Paris and London. Budapest is in its post-Communist state right now, so it shares some similarities with a Western Europe still coming back from the war in the early ’70s. In Budapest, we were able to find the look of 30 years ago.”

To prepare for the shoot, Carter actually traveled to each of the cities where the assassinations took place, giving him a richer sense of what he was trying to re-create. A longtime collaborator with Steven Spielberg, the subject matter of Munich seemed in keeping with the director’s strongest themes. “I think of this movie as part of a series of movies that Steven has done on the subject of war and its consequences,” he observes. “He’s always looking at the ways that we find ourselves in strife.”

But Carter was acutely aware of a difference in Spielberg’s approach – one that was more stripped down to the characters’ deepest internal struggles. “All the attention in this film is on the drama, and everything starts with the five main characters and who they are,” he notes. “I think Steven found this approach very fresh and freeing. He seemed almost like he was a filmmaker in the ’70s.”

In his designs Carter attempted to stay away from standard ’70s visual clichés and focus instead on reflecting each of the local cultures through which the team travels. “What we would try to do,” explains Carter, “is put something in each scene that would allow you to know not only where you were in terms of the country and the era, but also a sense of the state of the culture. Are you in a place that has been influenced by the politics of the time, especially the radical movements that existed throughout Europe, or is it a place that has remained largely unchanged, like a fishing village in Cyprus that’s always been that way? Reflecting the mood of these very different areas was our biggest concern.”

In keeping with the film’s overall design themes, Carter’s color palette switched repeatedly, as scenes moved from one country to the next. However, he did have one consistent metaphorical color in mind: “There is the presence of red throughout the movie just as a reminder, subliminally, of the blood that runs through the movie on both sides of the equation,” he comments.

In recreating Europe in the ’70s, Carter’s designs also pay homage to the prevalence of cinema-with posters for Fellini’s Roma, Robert Mulligan’s The Other, The Hot Rock starring Robert Redford and L’Assasinat de Trotsky starring Alain Delon appearing in scenes. Another nod to ’70s cinema comes during a scene with Avner and Louis as they walk along a Parisian vegetable market. The scene was shot below the apartment made famous by Bernardo Bertolucci’s classic Last Tango in Paris.

While Malta and Hungary were the film’s primary locations, additional scenes were shot in the inimitable atmosphere of Paris. There was also another place for which Carter could find no double: New York City, the stirring skyline of which brings the film to a close and, in a sense, full circle. “In the quest to find a home, Avner eventually moves his wife and new baby to Brooklyn,” Carter explains, “which is like a new frontier, a place where he wants to start life over and leave everything he’s gone through behind him. We clearly couldn’t replicate that anywhere else-we had to go to New York.”

Meanwhile, picture vehicle supervisor Graham Kelly, whose work was previously seen in the acclaimed thriller The Bourne Supremacy, had additional challenges. With a schedule that called for 1,500 cars throughout the production, Kelly had to find and organize taxis, buses, Vespas and vintage automobiles dating from the period. For just one short scene in which Avner takes a walk at night on a Paris street, Kelly had to round up 60 cars, five Parisian buses and several Parisian taxis-all in Budapest.

“The ’70s are a particularly difficult period to do with cars,” explains Kelly. “Back then, manufacturers made cars of poor quality steel and most have rotted away or were far too collectable for our budget.” Kelly and his team purchased 60 cars from all over Europe, painting and repainting them as the scenes required. In sync with the overall visual theme, his team used bleached-out lighter colors on the vehicles for scenes in the southern countries and darker hues for northern locations.

The biggest problem, however, could not be resolved with paint. Kelly recalls, “We needed cars for scenes in four different countries in Malta. Malta has a good stock of ’70s cars, but they are all right-hand drive, like the UK. And with the exception of Cyprus, the other three countries were left hand drive! When we got to Hungary, the opposite applied. Hungary is left-hand drive and we needed to be in London for some scenes, which is right-hand drive.” With just a bit of ingenuity, “false” steering wheels and an extra driver per car, Kelly and his team solved their problem.

Costume designer Joanna Johnston also faced an intriguing challenge-crafting five different looks for each of the men on the hit squad that could reflect the individual background, personality and age of each character. “They each have their own mood,” says Johnston. “Carl, who is ordered, clear-thinking and practical wears sharp creases, straight-parted hair and bland colors; he has good presentation and never loses it. Robert, who is more poetic, artistic and sensitive, wears warm colors with soft patterns and textures and has a more rumpled look. Hans is the oldest of the group and an antiques dealer, so he is more old-fashioned and traditional in his style. Steve is the coolest of the group, fashionable in a street sense and very considered and sexy in his dress with leather jackets and tight shirts. Steven Spielberg’s reference point for him was Steve McQueen.”

The mood of Avner’s look, however, shifts as the story progresses. “To give a sense of Avner losing control, he starts the film dressing with an almost military precision with youthful, clean lines but then the sharp edges go, the warm colors of the country he hails from drop out,” Johnston explains. “He takes on the longer shadows of the north and an aura of suspicion. He eventually ends up in New York denim, the modern world, which he never would have taken on before.”

In addition to creating individual palettes, Johnston also forged geographic palettes for each country, matching the work of Rick Carter. “I used a lot of patterns and warm tones in Tel Aviv but the further north we went, the cooler and plainer the clothing became,” she notes. “Every country and city had an identification regarding its style and color. It was all very tightly choreographed.”

Creating about 85 percent of the costumes from scratch with her team in Munich, Johnston emphasized a more European and less clichéd ’70s fashion aesthetic. “The cliché ’70s are wild and crazy, but in Europe they were beautiful, elegant in a way. Steven said to me that I made it look `sophisticated with a twist,’” Johnston recalls.

“The costumes that Joanna has made are remarkable,” says Munich star Ciaran Hinds, “because she’s not defined just who these men are, but somehow has given a sense of how they think as well.” Hinds’ more philosophical and reserved character, Carl, always wears a suit and tie, often with the addition of a pipe and a hat. Hans’ clothing echoes his cover as a German antique dealer, with tweed jacket, shirt and sweater vests-accompanied, sometimes to the actor Hanns Zischler’s dismay on some of the warmer days in Malta, by a thick undershirt. Steve, played by Daniel Craig, is the only one with a flair for the fashions of the time. “Joanna had an idea that he would be the one character to wear something ’70s,” says Craig. “And I thought, `Well let’s go for it.’ I have the collars and the jeans and the medallion, but it’s kept quite simple.”

For producer and longtime Spielberg collaborator Kathleen Kennedy, the design of Munich was essential to accomplishing the film’s core mission: to bring to light secret events that raise a provocative and complex set of questions about the nature of vengeance and retribution.

“Rick Carter and Joanna Johnston did an absolutely remarkable job capturing the time and setting for this movie,” Kennedy says. “Their work comes through in a very understated, authentic way that strongly emphasizes the realism that Steven wanted to bring to the story. More than anything, I think that much like Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan, Steven wanted to capture a sense that this isn’t just a movie but a story that is based on something that really happened. If the film gets people around the world engaged in discussion, then I think we’ve succeeded.”

These production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

Munich

Starring: Eric Bana, Daniel Craig, Geoffrey Rush, Mathieu Kassovitz, Ayelet July Zurer, Ciaran Hinds, Brian Goodman

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Screenplay by: Tony Kushner, Eric Roth

Release Date: December 23, 2005

MPAA Rating: R for strong graphic violence, some sexual content, nudity and language.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $47,403,685 (36.4%)

Foreign: $82,955,226 (63.6%)

Total: $130,358,911 (Worldwide)