Tagline: Terror has a new name.

A psychological thriller about a military veteran who returns to his native Vermont suffering from bouts of amnesia. When he is accused of murder and lands in an asylum, a well-meaning doctor puts him on a heavy course of experimental drugs, restrains him in a jacket-like device, and locks him away in a body drawer of the basement morgue. The process sends him on a journey into the future, where he can foresee his death (but not who did it or how) in four day’s time. Now the only question that matters is: can the woman he meets in the future save him?

1991: Jack Starks, a U.S. Marine Sergeant serving in the Persian Gulf War, receives a near-fatal gunshot wound to the head. Although he recovers, the incident leaves him with shock-related amnesia. After his release, with nowhere to go, Starks, who has no relatives, returns to his native Vermont.

Nine months later, hitchhiking along a snowbound Vermont highway, Starks encounters a broken down pick-up truck. The driver, a drunken, disoriented mother named Jean, and her eight-year-old daughter, Jackie, are stranded at the roadside. With Jean too drunk to speak with him, Starks approaches Jackie and offers his help and gets the truck started. Starks continues hitchhiking, and is picked up by a station wagon driven by a young man headed for the Canadian border. Shortly afterward, the car is pulled over by the police and Starks blacks out. When he awakens, he finds himself on trial for murder in a small town court.

Found not guilty by reason of insanity, Starks is committed to Alpine Grove, a state institution for the criminally insane. There a staff physician, Dr. Becker subjects Starks to a jarring experimental treatment involving mind-altering drugs and claustrophobic physical restraint. Once medicated, Starks is wrapped in jacket-like restraints and left alone for hours at a time in a corpse drawer located in the hospital’s basement morgue.

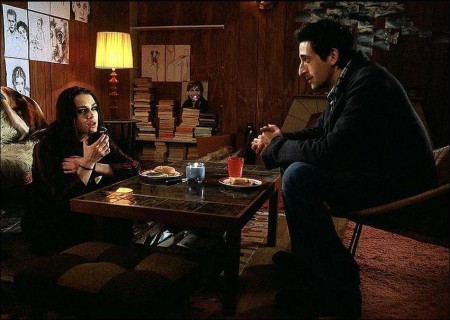

And in the drawer, in the dark and under the influence, Starks initially experiences flickers of memory from the war and the shooting of the police officer. Under this regimen, he begins putting together bits of his past and tries to make sense of his circumstances. The past gives way to the future when he is suddenly transported to a diner in Vermont where he meets Jackie, a waitress who takes pity on him and tries to help him find a place to sleep for the night. It is Christmas Eve, and all of the local homeless shelters are full, so Jackie allows Starks to sleep on her couch. In these hours, Starks begins to realize that the drawer he’s been confined to is the secret to his recovery and that his future and well-being lie in the hands of the girl he’s just met.

About the Production

As hopeful as it is harrowing, The Jacket, a mind-bending drama that melds elements of a thriller, romance, murder mystery and time-travel fantasy, is a film that defies easy categorization—which is precisely what made it so appealing to director John Maybury.

“What interested me about it is that was kind of genre-less,” says Maybury. “In a way, different audiences impose a genre on the film. I hope no one comes up with a label for it because for me, the fact that it slips between the cracks of various genres makes it interesting as an experience.”

Just as Maybury’s most recent film, Love Is the Devil, about artist Francis Bacon, was an unconventional biopic, The Jacket is an unconventional romance—fraught with suspense, tension, and an undercurrent of dread, but ultimately buoyed by optimism and a belief in the transcendent power of love. Not one to shy away from a challenging narrative, Maybury, who began his career as an artist, experimental filmmaker, and music-video director, embraced the story’s temporal shifts and the opportunity to bring his visual flair to the kinetic depiction of Jack Starks’ disorientation and bewildering flickers of memory.

Mandalay Pictures, lead by former studio head and longtime producer Peter Guber and Section Eight, the production partnership between Academy Award winning director Steven Soderbergh and actor-director George Clooney, then partnered to develop the script and to put the film together.

Section Eight partner Steven Soderbergh, who was greatly impressed by Love Is the Devil, sought out Maybury to direct the film. But getting Maybury, who was not accustomed to overtures from Hollywood, on the telephone took some effort. “I got a call from somebody claiming to be Steven Soderbergh which I didn’t believe,” Maybury recalls. “But when they called back and insisted that it really was Steven Soderbergh, I kind of believed him.”

Shortly afterward, when Soderbergh met with Maybury in London and described his and George Clooney’s vision for Section Eight, Maybury was intrigued. “He said he wanted to bring filmmakers like myself, Todd Haynes, Harmony Korine—filmmakers who are on the fringes not just of mainstream filmmaking, but on the fringes of independent filmmaking—and to bring us into the mainstream, to give us access to Hollywood studios, star actors and stuff like that,” says Maybury. “It seemed like an incredibly attractive proposition, so I asked him to send me some stuff and I’d see if there was anything I liked. The first thing they sent me was the screenplay for The Jacket, which was the first script I’d read from cover to cover in a long time.”

To prepare for the shoot, Maybury studied several films from what he refers to as “American New Wave cinema,” the late 1960s and early 1970s, including The Parallax View and McCabe and Mrs. Miller. His origins as a visual artist also prompted him to delve into the pre-sound era. “I watched a lot of silent cinema, particularly Eric Von Stroheim’s stuff, because he was doing experiments in the teens and 20s that for me still haven’t been resolved,” notes Maybury. “I come from the experimental avant-garde in England, so I have an awareness of a whole area of cinema that doesn’t usually impact on mainstream cinema. And that’s something I’ve tried to bring into play. I’d like to think that we’ve been able to employ various languages of cinema in this film, and hopefully seamlessly enough that they’re not so self-consciously heavy-handed that the audience will even be aware of that.”

Casting

For director John Maybury, taking the time to select talented, versatile actors for even the smallest roles gives him confidence to allow his cast the freedom to explore and take risks as they hone their performances. “I love working with actors, and I like to give them the chance to do what they do best,” he explains. “And the performances in this film are sensational. That’s across the board, not just the stars. The day players, and even some of the extras, do things that are kind of unexpected.”

For the lead role of tormented war veteran Jack Starks, Maybury chose Adrien Brody, who won the 2002 Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in Roman Polanski’s The Pianist—making him the youngest person to ever receive the honor. Prior to The Jacket, Brody was already well known to Steven Soderbergh, who cast the young Brody in his 1993 film King of the Hill. “Adrien isn’t your archetypal heroic leading man,” says Maybury, “but what he brings is an interesting, enigmatic quality to the role. And because he’s not the stereotypical hero, there’s a more of an edge and more danger to that character, which makes the character’s silences much richer and denser. It’s what he doesn’t say that’s interesting.”

Brody describes why he was drawn to the part, “What I’ve done when choosing work,” he says, “is to try to find things that continually challenge me and explore different aspects of human nature—either things I have experienced, or that I may not know about. To me, Jack Starks is a clean slate. The role is about who the character is, not where he is from and what his heritage is. Starks is searching for his identity, but is not bound to his past.”

While the audience is free to speculate as to whether Starks’ out-of-body experiences in the drawer are real or a product of his imagination, Brody’s goal was to craft a performance of maximum authenticity. “I have to exist in his world, so I have to make events real and logical for Starks,” he explains. “He has no sense of his past, but he has strength and a survival instinct, some of which may be attributed to his military training. And he possesses a quality that a lot of people don’t have—to look someone in the eye and expect the truth from them, because he is as honest as he can be. I’ve tried to tap into the stand-up guy within myself to put that across.”

Brody admits that the character’s psychological journey was a revelation to him. “Being in a mental institution when he is not insane, but is treated as if he is, and the realization that his experiences there could drive him insane, was shocking to me,” he says. “It gave me a greater understanding of how helpless so many people are, as victims of a system which controls them and keeps them down, whether in the military or mental institutions or being incarcerated by poverty.” He adds, “There is a possibility that a lot of what happens to Starks is what he sees in those moments before he died—as life flashes before him—elements of the life he led, or the life he wished he had led. But to me, Starks has to live as if, bizarre as it may seem, all these things are happening.”

Brody had seen Maybury’s film Love is the Devil, and found it deeply inspirational. “John has an incredible visual creative sense, a highly stylized but still intimate approach that reminds me of my mother’s photography,” says Brody, whose mother, Hungarian-born photographer Sylvia Plachy, has received numerous awards and accolades for her images. “It’s unique. As an actor is it difficult to convey everything about the story, and if a director doesn’t share your perspective, then some of your choices won’t translate onto the screen. John and I absolutely agreed on the essence of the character and the story. As a director, I’ve learned a great deal from him. He captures a closeness and intimacy that is sometimes lost in other films. For instance, he’ll shoot a close up of eyes in such a dramatic way that is as powerful as a sweeping landscape. That closeness allows the audience to feel they are watching your every emotion without ever being caught.”

Like Maybury, Brody was intrigued by the film’s absence of a distinct genre identity. “The Jacket can’t easily be defined,” he says. “There are fascinating elements—a love story, drama, and moments of horror. It’s not a happy story; it’s tormented with surreal moments, but in the end it is an amazing love story. Every man wants to have a woman like Jackie by his side—someone who supports you, but at the same time, you can solve their problems and make their life beautiful.”

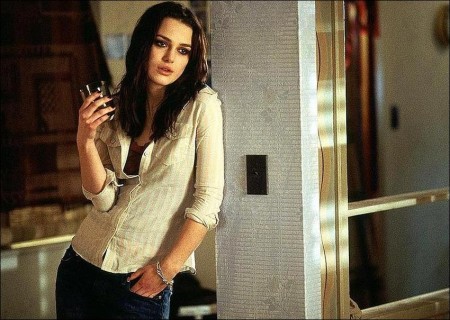

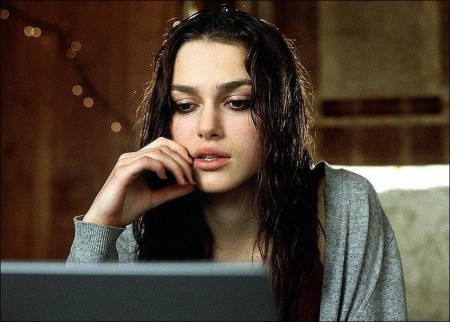

Co-star Keira Knightley read the Jacket script while on location in Dublin, filming the role of Guinevere in producer Jerry Bruckheimer’s medieval action drama King Arthur. “It was an exciting, imaginative script, and a role I wanted to play immediately,” recalls Knightley, who rose to stardom on the strength of her roles in Bend It like Beckham and Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl. “The other eight scripts on my pile were variations of the same pretty, uptight British girl, but Jackie was this damaged character who meets a guy going through trauma. It’s very rare that a film will show people who are in the process of self-destructing.”

On a rare day off from the King Arthur shoot, Knightley, despite a debilitating case of food poisoning at the time, traveled to London to discuss The Jacket with Maybury and the producers, only to arrive at what turned out to be a lunch meeting. “I spent most of my energy trying not to projectile vomit on these people I desperately wanted to work with,” she says.

Maybury’s words did little to abate the young actress’ queasiness. “He told me that he did not think I was right for the role, and he didn’t want me,” she says. “At that moment, I had nothing to lose. I declared that if I didn’t get the part of Jackie I could be stuck in corsets for the next 20 years, and asked him to let me read. He agreed, and promised if he was convinced, then he would hire me. We shook on it. I read the part, he gave me some notes, then gave me his phone number and offered me the job.”

“I didn’t want Keira Knightley for the role,” admits Maybury. “I’d met 15 to 20 young American actresses, and there were at least two or three that I thought would be terrific as Jackie, so very reluctantly I met with her. I knew she was an interesting, pretty girl, but that was it as far as I was concerned. The fact that she had food poisoning at the audition actually served to make her act and look even more Jackie like. Then, when she read, she was excellent, and I realized that she was a very intelligent girl and a very good actor. She comes across almost like a young Jane Fonda.”

Reflecting on Jackie, Knightley says, “She is stuck in her past, carrying a huge amount of guilt from the death of her mother. Even as a child, she felt responsible for Jean, trying to protect her from her problems, looking after her. And when we first see Jackie, she is becoming her mother—stuck in a small town, drinking too much, in a dead-end job. When she meets Starks she has nothing to lose, and she has no self-protection instinct. She picks up a stranger in a car park, offers him a ride, then lets him stay at her apartment, while she drinks and takes a bath. She is almost inviting harm in a reckless way.”

Gradually, as Jackie begins to believe Starks’ unlikely story, focusing on someone else’s problems gives her a new lease of life: “She chooses to take a chance; to let something happen to her.”

To achieve a believable transformation from sophisticated British beauty to small-town American diner waitress, Knightley relied on cultural cues provided by Maybury. “Jackie doesn’t look after herself, and uses her makeup as a mask—dark circles around her eyes, smudged mascara, messy hair,” explains Knightley. Maybury supplied examples of the influences he wanted her character to reflect, including Edie Sedgwick, a fixture of Andy Warhol’s Factory and star of his film Ciao Manhattan, who eventually selfdestructed through alcohol and drugs.

Aspects of Courtney Love are reflected in Jackie’s low, lazy voice, as well as a bit of Marlene Dietrich’s languidity. Maybury also gave her a tape of Laura Marano, who plays Jackie as a child, so that Knightley could connect in attitude and gesture with her younger self. “Laura has a direct way of talking, and a certain stance that I could carry through to the older Jackie,” says Knightley.

To reinforce Jackie’s isolation, Maybury encouraged Knightley to spend time alone when she was not working on set. The actress explains that this may have backfired on her director: “We decided that Jackie would listen to a lot of loud music, alone at home, and since I was living in the apartment above John, he got to hear a lot of Jeff Buckley, White Stripes, Nirvana and the Strokes.” Recalls Maybury, “It was a like living underneath a noisy teenager, as Keira liked to dance around her apartment.”

For the role of the well-intentioned but implacable Dr. Becker, a man disillusioned by years of treating the mentally ill, Maybury turned to Kris Kristofferson. “To me, Kris is an all-American hero,” Maybury says. “He’s a great country-and-western singer, a brilliant actor who’s appeared in some amazing films and, in a way, post-Johnny Cash’s death, he has almost segued into that position as a very important American voice.”

Maybury was especially pleased by the way Kristofferson’s iconic masculinity played off of Brody’s edgier screen persona. “In a parallel universe, Kris would be the hero and Adrien would be the baddie,” observes Maybury. “So the casting was a balance thing. Once I had Adrien in place, Kris made absolute sense as Becker.”

Kristofferson welcomed the opportunity to explore the different layers of what could have been written as a stock character. “I read the script and felt that I could bring to the role of Becker a realization from the audience that the man wasn’t simply a villain,” he says. “I can identify with his desire to help people, and I can understand how he has been beaten down by the system and the circumstances under which he works. I wanted him to be three-dimensional. There are very few totally evil people, although some people are undoubtedly more evil than others. A character is more interesting if he has more than one side, and that is what I hope I have given Becker.”

Assessing Becker’s conflicted nature, Kristofferson says, “He was an idealist to begin with, but most of the ideals he brought to the job, thinking he was going to be able to cure people, have been worn away. He hopes he can help Starks, though experience tells him that the man has gotten away with murder. He thinks that Starks is a liar who remembers what he has done. But Becker retains an element of hope, right up to the point at which they kick him out of the hospital.”

The experience of making The Jacket reinforced Kristofferson’s empathy for those who work in the mental-health field. “I wonder if the job attracts people who may be a little nuts themselves, or if they are affected by the environment,” he says. “Access to medication causes a lot of doctors to succumb to temptation, and the pain that Becker is around every day would lead him in that direction. I can understand that, being in the music business, where a lot of people use that same medication. Watching documentaries in preparation for the role, I noticed that it is sometimes hard to tell the patients from the doctors. It’s not a job I would care to have for any longer than the duration of making this film.”

But as emotionally draining as the film could be at times, Kristofferson relished the opportunity to work with Maybury. “John creates a great working atmosphere; it feels like an ensemble cast,” he says. “I’ve been lucky enough to work with a lot of good directors—Sam Peckinpah, Martin Scorsese, and John Sayles, for example—and I know the atmosphere begins at the top and is reflected in the whole outfit. This has been a very good set all round.”

The role of Becker’s colleague Dr. Lorenson was originally written as a man, but one of Maybury’s first changes in the script was to make the character a woman. “If you have two men fighting over a patient and the ideology of how patients should be treated, there would be an element of machismo involved,” Maybury says. “But if you took one of those male characters and made it a female, than a completely different dynamic came into play. A male-female conflict, for me anyway, is more interesting and more subtle, and that had enormous implications for how the story unfolds.

“On one hand, Becker is using very unorthodox, very dangerous treatments on the patients, and the Lorenson character seemingly is much more sensitive to their needs,” he continues. “But in fact, as the story unfolds, Lorenson is also doing very unorthodox things outside of the hospital. And within the hospital she betrays patient confidence and she betrays her colleagues, so for me, she is actually much more subversive as a character, although superficially Dr. Becker is much more dangerous.”

To convey Dr. Lorenson’s complexities and contradictions, Maybury was thrilled to have Jennifer Jason Leigh join the project. “Jennifer is astonishing,” enthuses Maybury. “It’s what Jennifer Jason Leigh doesn’t do that’s incredible. It’s her stillness on camera—the smallest of gestures become colossal on the screen. I know that Keira studied Jennifer in the couple of scenes they had together and was completely blown away by what Jennifer was doing. I will definitely work with Jennifer again because I’ve never really experienced that kind of intensity. Her restraint is incredibly powerful, and she brings a phenomenal kind of gravitas to the world that isn’t on the page at all.”

Maybury was equally scrupulous about casting the smaller supporting roles. “I was incredibly lucky to have Kelly Lynch and Brad Renfro,” he says, “They are both so talented. When people see Kelly Lynch playing Jackie’s mother, I wanted them to bring the history of the character that Kelly played in Drugstore Cowboy, as if that character hadn’t died—well, here she is twenty years later with a teenage kid. And similarly, Brad Renfro has kind of a wild history, but he also happens to be a brilliant actor, so that’s an extra added bonus.”

Maybury reunited with Daniel Craig, who played one of the leads in Love Is the Devil. Craig’s participation gave the director a reassuring familiarity, and his talent was essential to the believability of a small but crucial role, that of Mackenzie, the mental patient who befriends Starks at the institution. “I’ve worked with Daniel before, he’s a personal friend and I know his ability as an actor inside out,” explains Maybury. “And also, he’s actually the only person in the whole film playing a mad person. If you’re making a film about an asylum, the one person who is crazy needs to be a pretty good actor.”

As with nearly every aspect of the production, Maybury’s goal with the acting in The Jacket was to blend sensibilities here with his own. “For me, the pacing of the performances is very European,” he says. “It is inspired by Fassbinder, because he’s my biggest influence, and a kind of European sensibility. By that I mean the work of my favorite filmmakers: Passolini, Rossellini, Fassbinder, Herzog. There’s a different kind of tone and texture to the performances in their work that allows you to linger on a face, to linger on a performance.”

In this as in so many other respects, Maybury’s background as an experimental filmmaker and his reverence for European art cinema would seem to be at odds with the formal narrative and aesthetic boundaries of Hollywood filmmaking, but he does not see it that way. “Although I come from experimental film, I made music videos for five years, so I did have a brush with huge audiences in that respect,” he says. “Love Is the Devil was my first attempt to move from my avant-garde, experimental past towards more conventional cinema.”

These production notes provided by Warner Independent Pictures.

The Jacket

Starring: Adrien Brody, Keira Knightley, Kris Kristofferson, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Kelly Lynch

Directed by: John Maybury

Screenplay by: Tom Bleecker, Marc Rocco

Release Date: March 4th, 2005

MPAA Rating: R for violence, language and brief sexuality / nudity.

Studio: Warner Independent

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $6,303,762 (29.8%)

Foreign: $14,822,463 (70.2%)

Total: $21,126,225 (Worldwide)