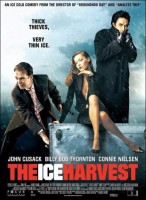

Tagline: Thick Thieves. Thin Ice.

It’s Christmas Eve in rainy, icebound Wichita, Kansas, and this year Charlie Arglist just might have something to celebrate. Charlie, an attorney for the sleazy businesses of Wichita, and his unsavory associate, the steely Vic Cavenaugh, have just successfully embezzled $2,147,000 from Kansas City boss Bill Guerrard.

Even so, the real prize for Charlie would be the stunning Renata, who runs the Sweet Cage strip club. Charlie’s fondest Christmas wish is to slip out of town with Renata. But, as daylight fades and a storm whirls, everyone from Charlie’s drinking buddy Pete Van Heuten to the local police begin to wonder just what exactly is in Charlie’s Christmas stocking. For Charlie, the 12 hours of Christmas Eve are filled with nonstop twists, both on the ice and off.

About the Production

In his work, filmmaker Harold Ramis has always coaxed refreshingly offbeat humor from everyday life. His latest film, The Ice Harvest, mines comedy from people behaving recklessly on Christmas Eve, catching them as their various foibles – and worse – collide head-on.

“We get so much Christmas glop every year – all those albums, and the first 50 times you watch It’s a Wonderful Life, it’s nice, but…The Ice Harvest definitely runs counter to all that,” says Ramis.

Upon reading Scott Phillips’ novel The Ice Harvest, producers Albert Berger and Ron Yerxa of Bona Fide Productions felt that they had found their next movie. Yerxa remembers, “It’s refreshing to see something so irreverent unfolding on a holiday that’s been gummed up with so much commercialism. Also, I was immediately intrigued by the idea of spiritually homeless men behaving badly on Christmas Eve, and by the story taking place in one night.”

Ramis remarks, “For me, the best comedy comes from reality. There’s nothing that’s written as a joke in The Ice Harvest; no one’s trying to be funny. It’s a film noir – with laughs.”

Berger comments, “The novel was a compelling crime story with interesting characters. Plus, it’s set against – in more ways than one – the Christmas spirit. That contradiction captured my attention. With men of a certain age, on Christmas Eve with no place to go, left with no other choice but to behave very badly, there was also something poignant about it. Ron and I like to make movies, such as Election, about contemporary America that are both funny and sad.

“Scott Phillips had been a screenwriter before he became a novelist; this was his first novel. I think he had written this with one eye on the movie screen.” Yerxa states, “Scott laid out the story with a great acid wit – the novel is very dry. It was excellent source material for a movie.

“We’re big fans of Harold’s work. He has a very funny existential take on the material, and he, over 25 years, has done some of the best comedies in American cinema. His interests in philosophy and existential humor complement his own unflappable calm nature – and make him a seriously funny storyteller.”

After landing the option on the book, the producing partners were contacted by another creative team: Academy Award-winning writer/director Robert Benton and Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Richard Russo. The latter duo had previously collaborated on two movies, and were now keen to adapt The Ice Harvest for the screen. Berger remembers, “They sought us out because we had the rights. As producers, having two major writers come forward and approach you is a home run. We all decided to work together and form an alliance.”

Ramis notes, “Richard and Robert have not only great ears for real dialogue but also great sympathy for the human experience. Their screenplay had even more compassion than the book, without going Pollyanna-ish or sentimental. They understood where people can be, spiritually and emotionally, at Christmastime.”

“It was very different from anything that Harold had directed before, and smaller than what he usually does,” admits Berger. “I think it was very appealing to him to try something new, in a darker arena he hadn’t yet explored. With Harold, there would also be that assurance that comedy would still come through.”

Ramis explains, “I don’t read crime fiction, but I love it in movies. Reading this script, it first appealed to me as a filmgoer and then as a filmmaker. That’s critical for me when I’m considering a piece of material. In order to do a movie, I have to want to see it badly enough. People will say The Ice Harvest is a departure for me, but my decision-making process was the same as it has been.

“I have – I would say – a cynical worldview. At the heart of this story is a grim existential reality that I find somehow amusing. Increasingly, the world seems to be operating without real spiritual values. Our culture pays lip service to higher values. But where do we really see them? We don’t see them in foreign policy. Certainly not in government, and we don’t see them in people’s moral behavior.”

Yerxa comments, “Charlie calls Christmas ‘God’s Birthday.’ Yet, people celebrate Christmas in a very commercialized way that has nothing to do with the myth of Christmas. That’s a contradiction in American culture – and a serious topic that we have chosen to approach humorously without attempting to do a comedy per se.”

Ramis adds, “Charlie has not taken action in his life. He’s been paralyzed with the pointlessness of it all, and he’s not really committed one way or another to anything. He’s plunged into an adolescent male fantasy that a lot of men take into midlife: ‘Gee, what would my life be like if I lived alone, did whatever I wanted, slept as late as I wanted, went to strip clubs, and smoke and drank as much as I wanted?’ His whole purpose, or lack thereof, is finally channeled into one single act that has consequences for a number of people.”

The part called for an actor who could be at once sympathetic and lost. Berger comments, “John Cusack brings a boyish optimism and likeability to all of his characterizations. I think the audience brings a connection to him that this particular character subverts.”

Yerxa adds, “John makes a great Everyman. He has an accessibility, and also a sadness and world-weariness that he is able to convey in Charlie.”

Ramis remarks, “John is not a tentative person. But he is a deeply thoughtful man who questions things. He and I talked about the concept that Charlie can barely feel pleasure any more. There’s a term for that – ‘anhedonia,’ the inability to feel pleasure – ”

“— and a great twenty-dollar word,” confirms Cusack, who adds, “I see Charlie as a very bright person who has slowly drifted into an abyss. His life has been compromised. Now he’s basically numb, and the night he has is one of those where you keep drinking yet somehow can’t get drunk. Probably because, with all that happens, his adrenaline finally has to get going!

“I could relate to Charlie in some ways. It’s great material, and I have always wanted to work with Harold Ramis; we’re both Chicago guys, and he has been part of a lot of iconic film moments, either as writer, actor, or director. He’s smart about material, and concentrates on character motivating plot, not the other way around.”

Concentrating on the character of Vic Cavanaugh, Ramis notes, “Unlike Charlie, Vic is not intellectually conflicted at all. He sees only his own desires and works totally from his gut. Vic is all instinct; he doesn’t even think later about what he’s done.

“One of my theories in life is that, from the time we’re little children, we’re looking to be taken care of and feel safe. It’s like having a friend in school who can actually fight, if you’re not a fighter yourself. Vic represents a stronger, tougher guy to Charlie – and an enabler, too.”

Billy Bob Thornton was sought by all concerned to play the sardonic Vic. Berger notes, “He just seemed a natural for this part. Nobody combines humor and menace like Billy Bob. As an actor, he’s always looking for a challenge.”

Yerxa adds that the actor “puts a lot of spin on the ball. You never know exactly where he’s coming from – charismatic, macho, intimidating.”

Ramis comments, “Billy Bob has got a lot of colors. He loved the character of Vic, the deviousness. Interestingly, when he arrived at the shoot, he said, ‘Now that I’m doing Vic’s part, I’m not reading other parts of the script, because Vic doesn’t care about anybody else.’ John seemed genuinely excited when Billy Bob arrived, and I soon understood why; he’s fun to have around. Their rapport comes through.”

The two men had established that rapport six years prior, while starring as nemeses in the comedy Pushing Tin. Cusack enthuses, “We had a great time back then, and we always wanted to do something together again. Billy Bob is a good friend, a great guy, and an incredibly talented man. We both like working the same way, finding the scene together and improvising. This script was so good, though, that we didn’t need to.”

Thornton remarks, “It’s a well-written script. That always comes first for me. I have a lot of respect for Harold; he’s one of my heroes in the comedy world. And John is one of my favorites; I love working with him. Out of all the actors I’ve worked with, the most generous relationship I’ve probably had is with John. He’s always willing to go wherever you want to. If you want to improvise, he’s right there with you. Out of the actors I’ve worked with, he’s probably the best at it.

“I love dark comedies that are set in a world of knucklehead criminals. The interesting thing about The Ice Harvest is that, normally, John would be playing the fast-talking slick guy. This time, I am. That attracted me, playing the guy driving the bizarre plot. Vic is Charlie’s twisted mentor. He’s the guy you went to school with who would tell you, ‘Oh, come on. It’ll be okay. Let’s go do this, let’s tear the logo off the police car.’ The fun part about playing a guy like Vic is that you can do things that you can’t do in real life.”

That same rationale also applies to the movie’s third lead character. Stepping into the seductive pumps of Renata – no last name, just “Renata” – is actress Connie Nielsen.

Ramis comments, “In the script, Renata is described as incredibly beautiful – so much so that the men in a strip club stop looking at the stage when she walks through the place fully dressed. She’s captivating, not only physically but because of her accent – which no one can identify. In our imagination, she is probably Eastern European and has that aspiration and drive which many recent immigrants have, the ones who come from a better life and then find themselves in reduced circumstances here. She’s looking forward to better, and she’ll do anything to get it.”

Berger says, “You wonder, ‘How did she end up in this town?’ Renata had to be intriguing to the audience, with a certain exoticism and class, in the same way that she captures Charlie’s imagination.”

Cusack muses, “There’s always some unattainable female who is supposed to make the laws of gravity not apply any more. If you can have her, if you can capture her, then life is going to be easy and you’re not going to have any of the problems that you’ve had up to this point…which is, of course, totally insane. But Charlie wants that promise, and in Wichita, Renata is ‘it.’”

Nielsen explains, “Renata is somebody who doesn’t belong to anybody, and I don’t even know if she belongs to herself. She’s out for only one person – herself. Harold and I decided to go for not so much a specific character as a spin on all the clichés of a femme fatale and all these notions that we have about these women. But I had a lot of fun playing, and playing with, the extreme manipulation that is inherent in such a character.

“I was actually a little worried about the part because I’m very much somebody who does not like the whole arena of flesh merchants. But parts of Renata’s heart don’t exist, I guess, which is a sad part of her character. Christmas Eve is just another night for her.”

The actress adds, “To play her, I had to go into a seductive way of speaking and adopt a really low voice register. Renata has an accent just like mine, and nobody in the movie knows what it is.”

Ramis comments, “Connie’s is a hard accent to identify. She’d never before done a film where she uses her real accent, but in this one she does.” Thornton reveals, “Connie is from Copenhagen, Denmark – and she is perfect in this part!”

An even more complicated relationship for Charlie is his friendship with architect Pete Van Heuten. The latter is now married to Charlie’s ex-wife and is stepfather to Charlie’s children. But, as Ramis notes, “they were friends before – and they’re friends now.” Pete’s key talent is his seemingly bottomless capacity for alcohol consumption, which gets put to the test on Christmas Eve.

Ramis adds, “For guys like Pete, it’s become harder to define themselves as men. The character has some great lines about how there’s little left in this country today for men.”

“Pete is a wild card,” notes Berger. “It’s a real movie-stealing role, and Oliver Platt jumped in with gusto.”

Cusack enthuses, “The way Oliver plays him, Pete is Falstaffian! He goes on one of the greatest benders that I’ve ever seen depicted.”

Platt says, “I was attracted to the writing, which offered a very clear picture of who this guy is. I enjoyed filling in more myself. Pete is drinking because of all the emptiness he feels. The early stages of a bender are pretty fun – before you black out or throw up.

“Harold was absolutely an incentive to do this picture. He’s made movies we all grew up on, the comic styles of which have informed so many movies that came after. Also, I’ve always admired John as an actor, and wanted to work with him.” Platt got along so well with Cusack that, not letting as much time go by as Cusack and Thornton had since Pushing Tin, the two have since made another movie together – Menno Meyjes’ upcoming The Martian Child.

Rounding out the cast is Randy Quaid, who was first directed by Ramis over two decades earlier in one of those influential comedies that Platt cited – National Lampoon’s Vacation. Quaid takes a 180-degree turn from his goofy Cousin Eddie characterization established in the earlier film to play the no-nonsense crime boss Bill Guerrard. Ramis muses that “Randy plays him as just a businessman trying to do what he needs to do.”

Aside from getting into the proper – jaundiced – holiday spirit to begin work, the cast and crew faced the question of just where to shoot the movie. Albert Berger, John Cusack, and Harold Ramis are all Chicago natives who still have homes there, and who strive to bring business into the city. With a potent assist from the Illinois and Chicago Film Offices’ tax credit plan (a wage-based incentive program) and the Illinois Production Alliance, The Ice Harvest was able to film in and around the city’s northern suburbs and in Waukegan, standing in for Wichita.

Ramis remembers, “Scott Phillips confirmed for me that Wichita in fact looks like the Chicago suburbs. He said that it doesn’t have a western flavor; it feels like the nondescript Midwest.

“The challenge was, ‘Can we get the Chicago budget down competitively?’ For that, everybody – the unions, the directors’ guild, the teamsters – got together, and we were able to get the film in.”

Berger states, “The state of Illinois worked hard to make it possible for us to film there. It was a group effort. We also had to set a production pace and keep to it, with no margin for error.”

Ron Yerxa adds, “We had a really good crew – and were able to finish principal photography in exactly 40 days.” Or, more accurately, as Berger notes, “We were on nights for most of the movie!”

Ramis admits, “We were wondering, ‘Could this be done?’ Because we also did a pretty short prep – seven weeks, as opposed to the three to four months I would normally take. But I was quickly reassured by the quality of the crew that we had in Chicago, as well as the skill of our producers and production manager. As a director, it was the shortest schedule I’ve ever had – and one of the best experiences I’ve ever had. “I was on one big movie where the only positive aspect that I can recall was that there was smoked salmon on the set in the morning. More time and more money don’t translate into a better filmmaking experience.”

Giving his full blessing to the project, Scott Phillips visited the set several times, and found his treks through Chicago-by-way-of-Wichita to be “surprisingly enjoyable.”

One of the project’s non-Chicagoans, Billy Bob Thornton, states, “I loved filming in Chicago. It’s a great town, with probably the best food of any city in the U.S. – for my money, anyways. The people are friendly. The weather is changeable, but you can put up with that…”

While it was a challenge to shoot a movie set on December 24th/25th in springtime, Berger, having previously produced the aptly named Cold Mountain, says, “There are advantages to not working in freezing cold; you can think clearly and move around a bit. When you create your own rain, you can control it.”

Yerxa clarifies, “Given the title, we created ice, too. But Harold said that another title for the film could have been Nothing Like Christmas, and so we made it a rainy, dismal Christmas instead of a jolly, snowy Christmas.”

“A wet Christmas instead of a white Christmas,” laughs Ramis. “With ‘just’ freezing rain, you’ve got treacherous conditions. We did also have tons of shaved, frozen ice ready, on a truck, that we could lay down anywhere.”

Cusack comments, “Harold told me that he gets lucky with the weather on all of his movies. Sure enough, it was a chilly spring in Chicago after all.”

Computer graphics also lent an assist, eliminating the burgeoning green of a Chicago spring to maintain the image of the flat and wintry Wichita landscape. To keep that consistency, Ramis worked closely with cinematographer Alar Kivilo and production designer Patrizia von Brandenstein to maintain the appropriate look and feel for the movie.

“The film is kind of a colorful noir,” reveals Kivilo. “We’ve embraced some of the classic noir elements like contrasting lighting, pools of light, and lurid colors. We start off a bit more naturalistic, but as things come to a head in the story, it has become more colorful – albeit still in a very dark way.

“Harold and I talked about where the right place for the camera would be. I always feel that, even if it’s for only one take, it’s worth doing a full master shot so everybody knows where you’re going – and then we’ll see where instincts take people. In The Ice Harvest, we have some tableaus, but when things get tougher for Charlie there is more handheld work that is rougher around the edges. The camera movement tries to capture the emotional content of the scene. On this shoot, we concentrated on what we really needed to tell the story. Patrizia, with whom I’d worked before, was so helpful in that regard.”

Ramis states, “Alar and Patrizia are so talented, and they work so well together. Patrizia is very resourceful, with a terrific eye, and I knew she would have a great understanding of the material. Within our budget, she was able to create these amazing strip clubs – ”

“ – the Sweet Cage, the Teaze-O-Rama, the Velvet Touch…thanks to Patrizia’s panache, they all look slightly better than what you’d find in Wichita,” laughs Yerxa.

Connie Nielsen, who spent the majority of her scenes on the Sweet Cage set, confides, “I’m a bit of a shy person, so it was weird to walk onto the set the first day and see a stark naked girl dancing on the stage; I wanted to run over with a sheet for her. Given the weather conditions called for in the story, at least I was inside most of the time.”

The film’s most crucial outdoors sequence unfolds far away from the overheated indoor milieu of the strip clubs. Coordinating man-made rain and ice with actors, stunt men, and water on a “frozen lake” in May found everyone honing their skills. “It took a lot of work to get that particular location ready, and I think it turned out great,” says Berger. “Patrizia designed a spectacular set which perfectly expressed the comedic and philosophical themes of the film.”

Yerxa explains, “To make the lake, we built a water tank on the stage we were using. But we also went out on location, at a land reclamation project. There was no lake actually there, so we created a mini-lake.”

As part of the preparation for the filming of the sequence, Kivilo reports that there were “detailed storyboards so that each department was on the same page – literally…”

For the more labor-intensive outdoors portion of the film’s lake, Ramis reveals, “We were at the bottom of a dry, open field in the middle of nowhere. We built a 65-foot pier out into it in a little hillside, and sunk a swimming pool into the ground, deploying asphalt and a pond liner. Then we filled it with water and melted paraffin on hot plates. When the paraffin hardens, it looks just like ice, and it was poured out where we needed it. The water was topped off by a wax layer. We had huge cranes standing by with rain towers. It was difficult to shoot.”

One member of the team found it a bit more difficult than the others. Berger notes, “Billy Bob doesn’t like being in the water much. That added a particular intensity to his performance, which worked quite well.”

Yerxa adds, “We were very careful that Billy Bob would not be working in water as deep and as cold as it appears.”

Thornton says, “Yeah, I’m not big on water. But when you’re an actor, you just get in there and do it once they call ‘action.’ It wasn’t so bad.”

Much more to the actor’s liking was his collaboration with the director. Thornton reflects, “Harold is laid-back – and that’s kind of deceptive. The whole time, he’s watching everything; he gets everything. As an actor, that makes you feel good because you know you have a safety net. He’s not going to let you do something that’s not quite good enough and move on; he’ll make sure it’s what we’re looking for. He draws you to him because you want to know what he thought.

“And you’ll go up to him and say, ‘Was it okay, Harold? Was it good?,’ and he’ll say, ‘Yeah, it was good. We’ll move on.’ In other words, he never kisses your a–. He keeps you alert all the time, so you don’t get lazy.”

Cusack states, “Harold sees everything. Yet he is laissez-faire, in that he gives people a lot of freedom. But he gets what he needs, and he gives you a lot of confidence.”

“He makes you feel safe,” remarks Nielsen. “You feel that you can go in any direction – it’s great when he comes back laughing – but when necessary he will say, ‘All right, let’s take it down a bit,’ or ‘Let’s go for another side.’ He leaves you a lot of freedom, but at the same time he doesn’t leave you stranded.”

Platt says, “Harold creates the best kind of set to be on; there’s permission to mess around, and then when he comes to talk to you, it’s perceptive and constructive.”

Kivilo notes, “I’m a firm believer that creativity comes out of a good spirit, and not from negativity. Harold keeps a very open, relaxed set. He’s open to everybody’s suggestions. His pragmatic approach to filmmaking is refreshing, because sometimes making a movie can get pretty crazy. When there’s screaming and shouting, it’s hard to create when you’re nervous. Actors feel comfortable in Harold’s environment; having acted himself, he understands them very well. That in turn helps me to do my job.”

“For better or worse, I’ve created this nice-guy image,” muses Ramis. “The trick is, I hire the right people and then I have very little to do. Maybe some gentle feedback or guidance…

“Directors like to take credit for everything that happens, because we all fantasize that being a director means being in control – when in fact you’re at the mercy of everything. I have my share of good ideas, and I’m the arbiter on what’s in and what’s out. Oddly enough, a lot of your work with actors happens after they’ve already acted. I love the editing room, which is where I get to decide what aspects of the performances I want to heighten or diminish. Maybe I get closer to the vision I’ve always had for the movie, after the actors have already done their explorations.”

With the film now edited and finished, Ramis feels that The Ice Harvest has evolved to include “plenty of mystery, lots of jeopardy, and a very surprising outcome.”

One of the film’s mysteries concerns an aphorism, written as graffiti, which haunts and taunts several of the characters throughout the long night and morning.

“‘As Wichita falls, so falls Wichita Falls’ was Richard Russo’s invention for the script,” says Berger. “Make of it what you will,” adds Yerxa.

“But, at the end of the movie, you do find out who’s been writing it,” reveals Cusack. Ramis clarifies, “The word play is, most people don’t know that Wichita is in Kansas and Wichita Falls is in Texas. It’s nonsensical – but it reinforces the movie’s take on the randomness of life.”

Nielsen adds, “Too few movies are made with the droll tone that acknowledges how we’re all bungling fools – at least a little bit – when it comes to life. I believe that comedy is more fun when it’s rooted in reality, as The Ice Harvest is. With the black-comedic slant and no honor among these thieves whatsoever, you’re in for a wild ride that is the polar opposite of ‘a Christmas movie!’”

These production notes provided by Focus Features.

The Ice Harvest

Starring: John Cusack, Connie Nielsen, Oliver Platt, Randy Quaid, Billy Bob Thornton, Monica Bellucci, Jenny Wade

Directed by: Harold Ramis

Screenplay by: Robert Benton

Release Date: November 23, 2005

MPAA Rating: R for violence, language and sexuality / nudity.

Studio: Focus Features

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $9,016,782 (88.8%)

Foreign: $1,140,186 (11.2%)

Total: $10,156,968 (Worldwide)