Tagline: Hell wants him. Heaven won’t take him. Earth needs him.

John Constantine (Keanu Reeves) is a world-travelling, mage-like misfit who investigates supernatural mysteries and the like, walking a thin line between evil and good. Constantine teams up with a female police detective, Angela (Rachel Weisz), who seeks Constantine’s help while investigating the suicide-like death of her twin sister. Does it have something to do with a mysterious group called “The First of the Fallen”? And what is it about Constantine that puts him in a position where he is making deals with representatives from both Heaven and Hell?

Based on the DC/Vertigo comic book Hellblazer and written by Kevin Brodbin, Mark Bomback and Frank Capello, “Constantine” tells the story of irreverent supernatural detective John Constantine (Reeves), who has literally been to hell and back.

When Constantine teams up with skeptical policewoman Angela Dodson (Weisz) to solve the mysterious suicide of her twin sister (also played by Weisz), their investigation takes them through the world of demons and angels that exists just beneath the landscape of contemporary Los Angeles. Caught in a catastrophic series of otherworldy events, the two become inextricably involved and seek to find their own peace at whatever cost.

About the Story

Imagine that life on earth exists in a state of détente, a balance between the forces of good and evil scrupulously maintained through the ages. Humans choose their own paths in this realm and, in doing so, seal their fates for the realm beyond; some bound for heaven and some for hell.

As part of this divine wager for all the souls in the world, both God and the devil are restricted from direct contact with the human race and its free will but are allowed a measure of influence intermediaries. Neither fully angels nor demons, these earthbound influence peddlers are best described as half-breeds. “Suppose you were very good in life, or very bad. They wrap your soul up in human skin and send you back on missions,” explains John Constantine, a man who has literally been to hell and back.

In ordinary bodies these half-breeds slip freely through the human population, doing their work. They share the roads, hold jobs, engage in myriad relationships with their human hosts and no one is the wiser. “They look just like us,” says Constantine director Francis Lawrence. “You could live side by side with them, maybe even be married to one of them or be friends with them and never know it.”

But John Constantine can see them. Since childhood, he’s had the unique ability – he would call it a curse – to recognize these beings for what they truly are beneath their fragile tissue of disguise. He sees their true faces, either beatific or demonic. Driven to suicide, in his youth, by this terrifying burden that no one understood, Constantine hoped for the peace it would bring but got instead a 2-minute tour of the depths of hell, a nightmare beyond imagination, before being resuscitated and snapped back into life.

Since that moment, he’s known the hellish fate that awaits him when his life on earth is ended, and has been trying desperately to change it. Finding the traditional path to salvation closed to him, he resolves to earn entrance to heaven by waging war on the demon half-breeds on earth. An expert in demonology and black magic as well as an accomplished con man when he wants to be, Constantine uses sacred relics as weapons, along with his wits, his fists and anything else at his disposal to send countless hordes back to the underworld in shreds.

But he is an unlikely hero. Spurred not by any benevolent intention, he battles evil only to buy his way into a heaven that is closed to him, and grows increasingly cynical as these efforts have no effect.

Constantine’s strange circumstances and embittered attitude are part of what attracted Keanu Reeves to the story and its title role. “It is one of the best scripts I’ve read,” he says. “It has humor, intelligence, vitality, and I especially appreciated how everything was not obvious. There’s mystery and contradiction. Constantine himself has a strong sense of morality yet his ethics are a little blurry. He’s trying to right some wrongs but he doesn’t always go about it in the nicest way. He’s an anti-hero I’ve never seen before.”

Constantly tormenting the renegade exorcist are half-breed entities from both sides. The angelic Gabriel (Tilda Swinton), God’s gatekeeper on Earth, continually denies Constantine the salvation he so fervently pursues. Unmoved by Constantine’s private war and aware of his selfish motives, Gabriel admonishes repeatedly – and none too sympathetically – that he cannot buy his way into heaven, while Satan’s emissary Balthazar (Gavin Rossdale) mocks his futile efforts and reminds him his days are numbered. Hearing of Constantine’s recently diagnosed terminal lung cancer, Balthazar is beside himself with malevolent glee.

Among Constantine’s few allies is Chaz (Shia La Beouff), his faithful driver and wannabe apprentice. Fascinated by what he sees of Constantine’s world, albeit from a safe distance, Chaz makes up for his lack of practical experience with an encyclopedic knowledge of the religious and paranormal, in avid preparation for the day when Constantine might finally ask for his help.

Constantine’s former comrade, Midnite (Djimon Hounsou) could be the source of more formidable help if Constantine hadn’t all but burned that bridge. Once a faith healer and witch doctor, Midnite claims neutrality and offers his nightclub as a sanctuary for half-breeds from both sides while keeping his true loyalties to himself. Now he warns Constantine to respect the balance. Still he persists. It’s the only thing he can do. It has become his life.

Called to the site of another demonic possession by his old friend Father Hennessy (Pruitt Taylor Vince), a weary priest whose body and soul have seen better days, he prepares for yet another exorcism. This time it’s a young girl in the grip of the underworld, the latest in a series of countless exorcisms that Constantine has performed and yet this one suddenly feels different to him. With disbelief and then increasing alarm Constantine realizes that the demon inside this particular child is fighting not for possession of her tiny body but for a way to break through it and enter the physical world, a blatant breach of the age-old balance. This cannot be happening.

But that’s just the first of several disturbing portents. En route home on the dark streets of downtown Los Angeles, Constantine is attacked by a demon – not a half-breed but a full-fledged demon, brazenly appearing on the earthly plane as if it had the right. Later, as he sits alone pondering these inexplicable and terrifying incidents he is approached by Angela Dodson (Rachel Weisz), a police detective with her own desperate questions about her sister Isabel’s mysterious suicide. Raised to believe suicide is a mortal sin, Angela cannot accept that her sister would take her own life, even though surveillance footage from the psychiatric hospital where Isabel was a patient shows her leaping from the roof. Based on rumors Angela has heard about Constantine, linking him to strange and supernatural events in the city, she seeks him out against her skepticism, in hopes that he might help explain what really happened to Isabel.

But Constantine isn’t the least bit interested in helping her. As Reeves explains, “He has problems of his own. He’s just been diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. He knows he’ll be landing in hell because of the life he took. His own. He’s busy looking for a way out.”

Consumed by his own concerns, Constantine at first turns her away… until he sees the hell-born entity stalking Angela as she walks away. He doesn’t know how, or why, but somehow Angela is a key to the bizarre demonic activity that is swirling around them both.

One thing he knows for sure: the balance is breaking down. Something big is brewing.

About the Production

Producer Lauren Shuler Donner was instrumental in helping John Constantine make his transition to the big screen from the pages of the DC Comics/Vertigo “Hellblazer” series of graphic novels. Shuler Donner, whose credits during her more than 20 years in the industry include the beloved Free Willy films, You’ve Got Mail and the international box-office phenomenon X-Men and X2, was captivated by the character’s extraordinary circumstances and distinct attitude. She saw the property’s dramatic potential as a feature film. “It was immensely appealing,” she says. “Intelligent, thrilling, a good story with an anti-hero at its core; the kind of movie in which the completely unexpected happens.”

After successfully pitching the project to Warner Bros. Pictures, for which she has produced a number of high-profile films including the Oliver Stone drama Any Given Sunday and the critically acclaimed romantic comedy Dave, Shuler Donner focused on developing a script for Constantine with screenwriter Kevin Brodbin (The Mindhunters) and producer Michael Uslan. Uslan, with partner Benjamin Melniker, also a producer on Constantine, have a long-standing collaborative association with premiere genre publisher DC Comics through which they previously helped bring the blockbuster Batman film franchise to life.

Brodbin, a huge fan of the source material (Vertigo’s longest-running monthly series with over 200 issues and 15 graphic novels published) had long harbored a desire to write a script for the character and took the adaptation very seriously, emphasizing that, “the most important thing was to be true to Constantine’s voice” – an essential point on which the filmmakers agreed, as did screenwriter Frank Cappello, who later joined the project and likewise drew heavily upon the character’s origins for guidance.

Based on the originality of the developing concept Shuler Donner presented, producer/writer Akiva Goldsman next joined the Constantine filmmaking team. A successful producer, Goldsman is equally renowned for his screenplays, among them The Client and A Beautiful Mind, which earned numerous honors including an Oscar, a Golden Globe Award and a BAFTA nomination, so it’s no surprise that it takes a strong story to capture his attention. “It’s impossible for me to work on something unless it’s fun as well as creatively and imaginatively engaging,” he admits. “Constantine presents an idea I’ve always found compelling and have wrestled with in my own work – that of the world behind the world, what might exist beyond what we can see.”

John Constantine’s identity and his attitude are inseparable from his situation; as the circumstances of his life compel him, he forges ahead with a single focus. “What I love about this character is that there’s an inevitability to his failure and yet he’s willing to keep pushing and trying to figure out another way,” says Lorenzo di Bonaventura, for whom Constantine marks his debut as an independent producer following an impressive tenure as head of production at Warner Bros. Pictures. “It’s not the kind of indomitable spirit that usually connotes a heroic venture; it’s the indomitable spirit of a man who knows he’s not going to win but plays as hard as he can anyway.”

“This is a man who walks both sides, light and dark,” Shuler Donner describes the complex title character. “He’s not evil; the life he took, after all, was his own. But he’s not all good either. Deep inside, I think he’s just a guy who’s had a very hard life and yet he’s smart enough to have a sense of humor about it, which is one of the reasons we wanted Keanu Reeves because we knew he could pull that off. He can strike those balances and give us the sense of depth that defines Constantine.”

“He’s fighting the system,” adds Erwin Stoff, Constantine producer and Reeves’ longtime professional collaborator. “John Constantine clearly doesn’t want to go to hell but he believes it’s his actions that should decide his fate, not someone’s technical reading of the rules. He’s a guy who, above all, cannot tolerate unfairness and hypocrisy and it’s the unfairness and hypocrisy he observed early in his life as well as his current situation that has hardened him to the degree that he is.”

Stoff felt so strongly about the Constantine script that he forwarded it to Reeves while the actor was in Sydney on production for The Matrix Revolutions and his instincts proved correct. “He fell in love with the character,” Stoff recalls. “He liked that fact that even though this had the potential to be a great, fun, epic-scale movie with amazing effects, at its center was a story about a man’s struggle with hypocrisy, with good and evil, and with what’s wrong in the world.”

Adds Melniker, “This is a unique individual who defies description. There’s an enduring mystery about him. It’s not commonplace; it’s not likely that people will say, ‘I’ve seen this before.’”

Uslan, whose youthful passion for comic books led to an early job writing for genre fanzines and a lifetime of avid collecting, believes that familiarity with the graphic novels is not a prerequisite to enjoying the screen story or appreciating the punch of Constantine’s personality for the first time. Having watched the character evolve for years in print he feels the film captures its essence in ways that count the most: namely, “mood, attitude and point of view. One of the great things about this story and these characters is that there is absolutely no black or white. As we learn to our horror, everything in life is gray. No matter how human someone appears there might be demons lurking within. When someone taps you on the shoulder you never know quite what you’re going to see when you turn around.”

Francis Lawrence, known for his award-winning direction on videos for some of the most dynamic acts in the music industry, has developed an expertise for recognizing the vital elements of a story and gauging their visceral impact. A film noir devotee, he says, “it was the character of John Constantine, the anti-hero, and the tone of the story, that attracted me immediately. The world he inhabits is unique and the story moves into places that were entirely unexpected.”

Intrigued, Lawrence researched the source material extensively, developed original sketches and ideas for the project and threw his hat into the ring as the production team was considering directors. He hit them like a bolt of lightning.

“If I could create one lie that I could tell for the rest of my career, I would say that it was entirely my decision to hire Francis,” Goldsman candidly confesses. “This guy is the real thing – he’s so good he’s scary.”

Contrary to the producers’ expectations, considering Lawrence’s background, he did not approach the material from a visual perspective. “His talent with visuals was certainly apparent but when we had our first meeting he talked for two hours about the script and the characters and never once mentioned the look,” recalls di Bonaventura. “Usually, when directors are making the transition from the video or commercial world they lean heavily on the visuals because it’s what they’ve been doing, so this was already staggeringly different than anything I had experienced in more than 13 years at the studio. More than anything, we were impressed with his ability to analyze the fundamentals of a scene.”

When it came to the imagery itself, Lawrence was more than prepared. “Francis arrived at our meeting with his drawings. In this business, of course, that means instead of coming in with your resume, in a suit and tie, you arrive in flip-flops with your 25 sketches of hell,” Goldsman remembers. “I was immediately taken by his idea that heaven and hell coexist with our world, and that when you pass from this spot in our world you should be in this exact same room in hell. He was very specific about the geography. It was a brilliant idea, it gave the unimaginable a new imagining and completely captured what the movie was about.”

Lawrence sought to present the landscape of the underworld in a new way. “I thought about the ways in which I’d seen it depicted in art, in the paintings of Bruegel and Bosch, or so often in an abstract way, like a black oily void. The images were nothing you could relate to. I wanted to give it a recognizable structure. So when Constantine is in Angela’s apartment and he momentarily crosses over into hell, it’s the hell version of her apartment that he’s in; when he goes out into the street it’s the hell version of Los Angeles. That makes it an environment that people can easily imagine touching and seeing.”

He went on to provide detailed descriptions of the various demons and spirits that inhabit the story and offered casting choices that proved right on the mark. “What was interesting,” says Stoff, “is that a tremendous number of the ideas Francis proposed in his very first meeting came to fruition.”

The director’s willingness to imagine things in a fresh way was the perfect approach for a story in which nothing is clearly black or white and the characters are anything but conventional: a hardened police detective looking for hope in the paranormal; an angel representing God on Earth while promoting a personal agenda; a priest unable to perform exorcisms; an entrepreneur who runs a nightclub for both sides….and in the middle of it all, a hero who doesn’t want to be a hero. As screenwriter Frank Cappello describes, “Here’s a guy who has his problems with God. Loathes the devil. He fights the most hideous demons and yet he cannot escape his own bad habits, like smoking, which is literally killing him. Ultimately he’s a man trying to save himself, not the world.”

“This is a movie where not everything is neatly explained,” says Goldsman. “The attempt was not to create full comprehension in the mind of the audience but to give them an experience.” Equally important, adds di Bonaventura, is that, “it doesn’t preach or try to convince you of anything. It allows you to have a simple entertainment on one level and then, perhaps, an intellectual, emotional or philosophic conversation. Let us scare you first, and you can consider the more profound questions later.”

Cast and Characters

Cast as the anti-hero John Constantine, Keanu Reeves played a part in developing the screen character, as Goldsman relates. “He just became Constantine so fully during the development process and rehearsals that a lot of the lines that ended up in the film just emerged from him. He obviously loved the role.” Director Lawrence notes the depth of darkness that “Keanu was able to pull up from deep within and bring to the forefront to play this role. The sarcasm is natural and believable, and indicative of how Constantine views the world. You really see how this man is haunted inside and out.”

With Constantine, attitude is paramount, a concept Reeves fully embraced. “Attitude defines Constantine,” says di Bonaventura. “Call it irreverence, fatalism, irony, bravado; it’s unmistakable.” Adds Reeves, “Constantine literally knows how the world works and he doesn’t like it.”

Clearly, what he does best is not a job he ever wanted, though it garners him a fair amount of pride, and that contradiction laid upon all the rest just adds to his trademark cynicism. Although, as Stoff remarks, “it’s often true that the most hard-boiled cynics are people who were once incredibly romantic and idealistic and have had their hopes and ideals crushed.”

Constantine is also abidingly rude and anti-social, which is part of the pleasure of portraying him, Reeves reveals. Describing the scene in which he turns Angela away when she comes for help, he says, “He’s just not in the talking mood. Plus, he doesn’t like people getting close to him because they tend to die so he’s more comfortable keeping his distance.”

The fact that Constantine later catches sight of a demon pursuing the departing detective and rushes to her aid Reeves finds questionable and typical of his character’s enigmatic nature. “Is his help self-serving, in whole or in part? Because it turns out, as Constantine suspects, this woman is somehow intricately involved in the recent escalation in demon activity and the larger plot behind it all that he’s trying to figure out. Is he helping Angela, as any of us would, simply because she’s in trouble, or is it just part of his big plan to save himself?”

Overall, “John Constantine is the most reluctant hero I’d ever come across,” states Brodbin. “He’s not doing things to be a nice guy or to be a hero. He doesn’t want to care about people because all it does is bring him pain. If he could cut that part of him out he would.”

“He definitely has an heroic arc,” says Goldsman. “But he goes kicking and screaming about it.”

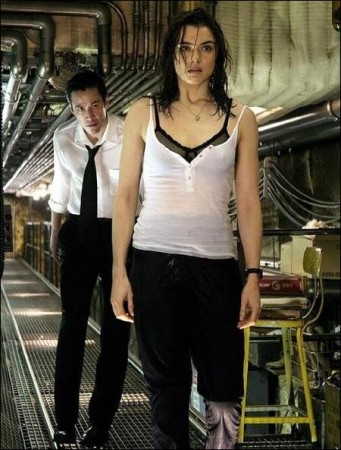

In the catalytic role of Detective Angela Dodson, the filmmakers cast Rachel Weisz (Enemy at the Gates, Runaway Jury, The Mummy). Addressing the duality of her character, Lawrence explains, “we needed someone believable as a competent police officer who turns out to be also a very powerful psychic. She needed to be tough, smart and also embody a quality that could make people believe there might be something else going on below the surface, something she’s not even fully aware of herself.”

Weisz’s research for the role included sessions with a police consultant for instruction in gun-handling and body language, and a local Los Angeles psychic. “Angela goes through a huge transformation in the film, from being a complete non-believer and cynic to slowly acknowledging the possibility of belief and ultimately re-discovering the psychic powers she’d been repressing since childhood. It was a very interesting progression to play,” she says.

Additionally, Weisz took on the role of Angela’s deeply disturbed twin Isabel, and observes that a great part of what propels Angela to seek answers about Isabel’s death is her own guilt. “Both sisters were psychic as children but while Isabel reported her visions and suffered the consequences from her strictly religious family, ultimately ending up in an asylum, Angela denied them and thus survived. Now she’s paying the price – not only with intense guilt but, like anyone who suppresses a big part of themselves, she’s not been living fully.”

Noting the chemistry between Weisz and Reeves, who previously worked together on the 1996 action thriller Chain Reaction, Lawrence observes that “there are several scenes between Rachel and Keanu that are quite dramatic, emotional moments.” As Shuler Donner sees it, “these are two people who have both devoted their lives to fighting evil, she with the law and he in his own way, so it’s natural that they would be drawn together. On a very basic level they are similar and understand each other.”

Shadowing Constantine nearly all the time is Chaz, played by Shia LaBeouf. Apprentice, sidekick, driver, friend – the origins of their relationship are not explained but Chaz remains a faithful, if increasingly impatient, presence. With no special abilities or heightened sight of his own, Chaz compensates with research and sheer enthusiasm. Fascinated with Constantine’s work, he spends all his free time compiling a body of religious and historic knowledge that he hopes one day to use if Constantine allows him to actually help on a mission.

“Chaz is insanely intrigued by Constantine and hero-worships him, wants to be him. It would be like a kid wanting to be Michael Jordan,” says LaBeouf. “Chaz is a talker. He’s not exactly comic relief but he is a bit comedic in that his personality is just a tad amplified, he speaks a little faster than everyone else and when he’s scared you can really see it in his face.”

Of course, the ambitious would-be protégé doesn’t fully comprehend the danger. “He wants very much to be a part of this world, which he sees as very glamorous, even though Constantine hates what he’s doing,” explains Lawrence. “He desperately wants to join up. Later in the movie he’s given the opportunity and realizes it’s a much different world when you actually go inside.

“He’s also the eye of the audience,” the director continues. “So many characters in the movie have some kind of gift or supernatural identities but Chaz is just one of us, witnessing these extraordinary events.”

Goldsman credits Will Smith for LaBeouf’s casting, recalling their recent work together on last year’s sci-fi feature I, Robot, for which Smith and LaBeouf starred and Goldsman shared screenplay credit. “Will came up to me while we were working on the film and said ‘this kid is great.’ So we tested him for the Chaz role and it was genius. Then I got to sound very smart by saying, ‘this kid is great.’”

For the role of Gabriel, God’s angelic representative on Earth, Lawrence came to the project not only with a fresh approach in mind but the perfect actress to execute it: Tilda Swinton, whose internationally acclaimed body of work includes standout performances in Orlando and Adaptation as well as a 2002 Golden Globe nomination for The Deep End.

As an angelic being, even in human form, Gabriel transcends gender. Lawrence wanted to represent the character as neither dominantly male or female and sought to accomplish this partly by casting a woman, dressed in traditional male clothing; but the costume would only take the impression so far, the crucial element being the performance itself. Not only would Swinton need to project Gabriel’s innate ambiguity in many forms, including gender, she would also have to be powerful, luminous and remote; not an easy interpretation.

“I liked the idea of Gabriel’s androgynous nature,” she says. “By the time the filmmakers spoke with me they had stopped talking about taking the character into either a masculine or feminine direction and had settled on a median, and we focused on how best to achieve that. Clearly, I didn’t want to look like one of the models from the Robert Palmer video.” Far from that, as Shuler Donner attests, “Tilda brings great elegance and class to the role, as well as a measure of sympathy, which is not easy considering the circumstances. Constantine calls Gabriel ‘the snob,’ and sees him as arrogant and uncaring.”

“As God’s gatekeeper on Earth,” Swinton explains, “Gabriel is the only entity Constantine can petition directly for a way to avoid going to hell. But each time he pleads his case the answer is the same: no. You need faith to enter heaven and Constantine is disqualified because faith is about belief without proof.”

Pruitt Taylor Vince takes on the role of one of Constantine’s few true friends, Father Hennessy. Once a strong and vital clergyman, Hennessy is now a damaged soldier in the battle between good and evil and relies on Constantine to perform the arduous exorcisms for which he no longer has the strength. But his years of experience have given the weary priest an acute sensitivity to otherworldly vibrations in the atmosphere. In return for Constantine’s help, Hennessy provides him a unique early warning system, “surfing the ether” for signs of demonic activity and subtle changes in the balance.

An Emmy Award winner for his portrayal of a killer in the mini-series Murder One: Diary of a Serial Killer, Vince warmed to the character immediately upon reading the script, even before knowing that Father Hennessy was the part the filmmakers had in mind for him. “I like flawed characters,” he reveals, taking note of the good father’s propensity for alcohol, among other things. “I prefer my heroes a little moody, darker, having a bad day.

That describes not just Hennessy but Constantine too – they’re not the heroes on a white horse. It’s a spotted horse. I believe Hennessy was really quite a priest, but still only human and eventually the demons, both inside and out, broke him. He’s seen too much and he doesn’t want to see it anymore, and climbing into a bottle is a good way to cloud your vision.”

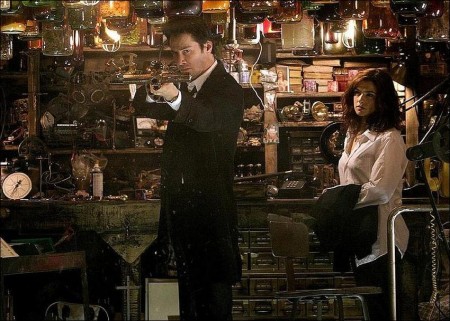

Another of Constantine’s enduring, if strained, relationships is with the one-time faith healer and witch doctor Midnite, played with inimitable style and grace by Oscar- and Golden Globe-nominated Djimon Hounsou. Now a successful businessman and collector of religious relics, Midnite honors the balance by operating an exclusive nightclub on a neutral basis, where half-breeds from both sides can mingle freely. “He’s strictly business now, that’s the path he’s chosen,” comments Hounsou, “yet you get the impression that he hasn’t forgotten where he came from. I love this character. Every time you meet Midnite, elements of his personality surface against his own will.”

Midnite’s true loyalties are as mysterious as his origins. “I believe he and Constantine used to run together maybe five or 10 years ago but when we come into the story things between them have changed,” Lawrence muses. “There’s been a misunderstanding, and a certain amount of distrust has crept into the relationship.”

Hounsou topped the director’s wish list for the part of Midnite even before Lawrence had his first meeting with filmmakers about helming the picture. “Djimon is an incredible talent,” he attests, citing the West African actor’s Oscar-nominated performance in In America, as well as acclaimed roles in Amistad and Gladiator. “He gives Midnite the kind of powerful and enigmatic presence the part requires but also a suggestion of sympathy. He ensures that Midnite is likable, even if we don’t know what to expect from him.”

One of the regulars at Midnite’s club is the vile and dangerous half-breed demon Balthazar, played with wickedly degenerate charm by Gavin Rossdale, frontman for the platinum-selling UK band Bush. “You hate this guy the instant you see him,” jokes Lawrence. “Balthazar’s so clean and pristine, so beautiful, just the opposite of what he is inside and Gavin gives him a great understated repulsive vibe. He takes on the character exactly.”

Adds Shuler Donner, “we wanted someone who was good-looking and suave and had more than a little bit of mischief in him.”

Fascinated by the script, Rossdale jumped at the chance to be in the film not only because of the story but “because of the caliber of talent surrounding me, people who set the standards.” In his pivotal scenes with Keanu Reeves, he explains, “Balthazar functions as Constantine’s tormentor and nemesis, so I played him as Keanu’s opposite. These characters dislike each other intensely.”

The most difficult aspect of the role proved to be learning Balthazar’s trademark one-handed coin roll, a feat of dexterity the guitarist admits took time mastering. “Your hands get a bit clammy after awhile,” Rossdale admits, remembering with a laugh that his first attempt in the early days of shooting involved performing the trick over a stairwell. “I said better bring in a good supply of coins for me and make sure no one’s underneath because I’m going to be dropping a bunch.”

For the brief but critical role of Balthazar’s boss, Satan himself, Lawrence found that his take on the character synchronized perfectly with that of internationally known Swedish actor Peter Stormare, right down to the white suit.

“The devil has been depicted so many times in literature and art that we all recognize him instantly,” says Stormare. “He usually has hooves and he’s a bit hairy, dark and horned. In my first conversation with Francis I said let’s do it without a lot of makeup and prosthetics; let’s just use my face and let the audience use their own imagination. When he walks down the streets of Los Angeles or any other city in the world he should look like the neighbor next door – a little odd, perhaps, if you look carefully, but nothing overtly dangerous.”

This echoed the director’s own sentiments. “What I felt I’d never seen was simply a bored, unemotional, kind of creepy guy along the lines of Fagan in Oliver Twist – in a word, insouciant,” says Lawrence. “He doesn’t need to get angry, he doesn’t need to make a scene or call attention to himself – he’s Satan, after all.”

Rounding out the main cast is Max Baker, who recently starred in Simon Wells’ sci-fi adventure The Time Machine, as Constantine’s friend Beeman, a scholar with a talent for acquiring ancient religious artifacts with powers to heal, protect or destroy.

Procuring such obscure items as a strip from Moses’ cloak, a screech beetle from Amityville or stones from the road to Damascus, he presses these potent relics into Constantine’s hands because, not being a warrior himself, it’s the only way he can help. “He’s a bit like Q is to James Bond,” remarks Lawrence, “the research guy, the one who keeps him stocked with one-of-a-kind supplies.”

Designing, Creating and Photographing

“Heaven and hell are right here, behind every wall, every window, the world behind the world. And we’re smack in the middle.” – John Constantine

It was an ongoing collaboration between production design, cinematography, visual and computer effects and Stan Winston’s creature artists to achieve the filmmakers’ vision for Constantine’s rich landscape, all of it coordinated and inspired by Francis Lawrence who watched as many of his original sketches expanded to fill whole soundstages.

John Constantine’s world is a dark and moody place. Visually, it’s the very definition of classic noir, with its urban night scenes, deep shadows, slivers of street lamps on wet asphalt and gently swirling smoke – all interpreted by skewed camera angles and expressionistic lighting. “The overall look,” comments Shuler Donner, “is saturated and beautiful, but gritty. It evokes a sense of period, in a way, but is totally contemporary.”

Lawrence met with renowned production designer Naomi Shohan, whose recent work on American Beauty earned her a BAFTA Award nomination. Seeking to realistically depict specific regions of Los Angeles, “not Beverly Hills, not Malibu but downtown,” the director explains, he was particularly impressed with Shohan’s natural-looking work on the urban drama Training Day, remaking that, “she really understood Los Angeles, the ethnicity and textures I liked, and we bonded instantly over the approach.” Together with location manager Molly Allen, Lawrence and Shohan prowled the city for the architecture and vistas of their story.

Among the sites selected were the Hacienda Real Nightclub, housed in the basement of the historic 1930s Eastern Columbia Building in downtown’s commercial and theatre district, which provided an appropriate eclectic and underground flavor as Midnite’s bar with its red-hued décor and ornately carved wood and brass detailing; the 5th Street Market, whose interiors and exteriors became the liquor store in which Father Hennessy and Balthazar have their final confrontation; St. Mary’s hospital, Long Beach, which doubled as Ravenscar; and the Angeles Abbey Memorial Park in Compton, as Midnite’s office and cavernous reliquary. Built in 1923, the Abbey interior features elaborate ironwork and carved limestone, which Shohan’s team augmented with statures, tapestries, artwork, religious relics and an assortment of antique weapons and armor to represent Midnite’s imposing collection.

Constantine’s apartment, unusually long and narrow, was designed in a place Lawrence with already familiar with, the Giant Penny Building on Broadway, downtown, whose upstairs interior office walls had been broken out to form an extended space lined with windows. Thinking it had great potential as Constantine’s home base, he showed the space to Shohan, who then added metal shutters to the windows and bottles of holy water that Constantine has lining the walls for protection.

Additionally, the production used six Warner Bros. Studios soundstages for such comprehensively constructed sets as the hospital’s hydrotherapy room, in which several climactic battles rage between the forces of good and evil, and a representative section of the 101 Freeway, which occupied nearly 22,000 feet and took eight weeks to complete.

Based upon the director’s premise that heaven and hell exist as parallel dimensions occupying the same space and that there is a heavenly and a hellish version of every spot on earth, Shohan explains, “I imagined the hellish transformation to any landscape would be a state of constant cataclysmic shifting – exploding, imploding, blowing, burning, decaying. Happily, Francis and I agreed that if you were in Los Angeles the quintessential hell version of the city would be a section of its infamous freeway.”

As Constantine attempts to confirm the afterlife fate of Angela’s sister, Isabel, he must visit hell to look for her, a treacherous journey on which he embarks from Angela’s apartment. The instant he crosses over he appears in a scorched and gutted version of Angela’s room, and from there climbs out onto the street and up to the highway, buffeted by fierce winds swirling with ash, with fire and chaos all around. “You can’t beat the image of Constantine walking down the center of a decomposed 101 Freeway in hell,” says Lawrence, and, going for the irresistible joke, “most people who live in Los Angeles think the 101 Freeway is hell already.”

Meticulously designed to look like the real thing, the section of road was built to nearly standard specs, with the exception of narrowing lane width from 10 to eight feet and laying three lanes instead of four. “Rails, dividers, lamp posts and signage were all built to highway department standards,” Shohan confirms. “The surface is concrete poured over wooden scaffold and dividers are concrete over carved foam.”

Among the set’s most striking details are the approximately 40 vehicles, racked up in various states of disintegration. As Shohan explains, “The cars are wrecks purchased from collectors. We wanted certain models for their particular shapes. These were then cut-up, re-configured and embellished with foam carving to make them appear mutated. We added wire and foam-formed stalactites to look like melted metal and everything was covered in latex-and-hemp pieces we made to have the appearance of skin with roots or veins growing in it. Finally, the whole set was age-painted in rust and brown to complete the look of waste, decay and constant diabolical transformation.”

Coordinating with Shohan to use this detailed practical set as a foundation and starting point, Visual Effects Supervisor Michael Fink replicated and extended it digitally. Wrecked cars were remodeled in the computer so that each one could be further eroded or blown away by acrid winds and so that digitally created demons and lost souls in hell could be moved around and through them.

Fink describes the look he was striving for, as “an incredibly harsh environment, like the aftermath of a nuclear blast except that instead of lasting nanoseconds it lasts forever.” A visual effects supervisor since the early 1980s on a range of high-profile feature films, Fink counts among his credits an Oscar nomination for his work on 1992’s Batman Returns and more recently oversaw effects on the blockbuster hits X-Men and X 2, where he collaborated with Constantine producer Lauren Shuler Donner.

Craig Hayes, visual effects supervisor at Northern California-based Tippett Studio (The Matrix Revolutions, Hollow Man), led a team of artists who replaced the set’s green screens, incorporating photographic elements with digital design for what he calls “a fluidly dynamic effect,” grafting objects onto existing images and generally “adding debris, airborne particles and detritus, burning palm trees and the entire hell-L.A. environment.” In addition to extending and enhancing the focal point of the ruined roadway, the film required realistically scaled hell-scape vistas of Los Angeles extending out in all directions, “starting in Hollywood and going past the Capitol Records building to the right, all the way to downtown,” Fink outlines, “all of it pretty much seen as it really is, with some allowances for the scale to enhance the drama.”

Working closely with both Fink and Shohan as well as with Francis Lawrence, was Oscar-winning director of photography Philippe Rousselot (A River Runs Through It), a master at capturing mood. With more than 30 years in the film industry in both his native France and the U.S., and credits including 1994’s atmospheric Interview with the Vampire and more recently Tim Burton’s Big Fish, Rousselot’s ongoing priority is discovering new challenges. “I’m always looking for something different, and when something like this comes along, that I had never seen or even thought of before, it’s very motivating,” he says.

Basing much of his compositions and stylistic choices for Constantine on the graphic novel origins of the story, Rousselot explains that he incorporated “a lot of wide angles, both high and low, and the kinds of extreme points of view that you often see in comic books, which I thought was very important to maintain. In terms of light, we played a lot with contrast and colors, going with some very deep greens and oranges.” At the same time, the cinematographer was careful not to copy the comic book style, preferring a more subliminal effect and drawing inspiration from many sources, including a folio of photographs from Cuba that Lawrence shared with him. “You can’t transfer pages into moving images; it’s more the general idea of graphic novels that we were touching upon.” Equally subtle were his nuanced depictions of heaven and hell, avoiding “the clichés of light and dark.”

Overall, Rousselot opted for natural lighting, guided by Lawrence’s desire “to keep the light organic and simple.” But simple doesn’t necessarily mean small, as evidenced by the sheer number of lights used, in one instance, for Constantine’s sequence in hell. A total of 60 space lights hung from the ceiling of Stage 21, designed to move freely with the wind created by seven immense industrial fans positioned along one side of the freeway set. Their irregular movement provided an intensely dramatic quality. Additionally, Rousselot ran alongside his camera crew during many close-ups holding an extended pole with a paper-covered China light on Keanu Reeves – a personal touch that allowed the cinematographer to capture precisely the right effect.

Rousselot’s most precarious task by far was the bathtub scene, in which Rachel Weisz, as Angela, is fully submerged and held down by Constantine to facilitate her brief passage into the next world. “We wanted to have Rachel’s point of view while she’s underwater, when she opens her eyes and looks up. But of course there’s no room in the tub so we shot it through a mirror,” he says. Adding a mirror to the mix increased the potential of unintended reflections, already complicated by the water, which, Rousselot explains, “reflects not only images but all the practical light.”

The world viewed through John Constantine’s eyes is populated with a variety of demonic half-breeds who live among their human hosts, their true natures undetected and their hideous features thinly masked by human faces that they can transform at will.

Meanwhile, in Hades itself, demons roam and seplavites (soul-eaters) prowl the ruined landscape. Seplavites are a sub-genre of the damned, introduced in the film as soulless, sightless, mindless scavengers who rely on scent alone to scurry after and feed upon new arrivals in the underworld. Not surprisingly, they were inspired by photos the director had seen of medical cadavers with their brains removed.

“It was a striking image,” says Lawrence. “I had been trying to bring a human element into the design of the seplavites, because these are not wholly monsters; they were human at one point. They have no souls now, no brains, no eyes, just sinus passages and mouths, and little spindly bent bodies that can only crawl around after food.” In this, they are relentless.

In the film are hundreds of seplavites, all born from a single fully articulated puppet prototype created at renowned creature shop Stan Winston Studios, under the direction of Creature Effects Supervisor John Rosengrant (Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines). Based on illustrations from Lawrence, Naomi Shohan and Stan Winston Studios Concept Art Director Aaron Simms, the hellish scavenger was first sculpted in a computer. From that point, as Rosengrant details, “we had the form milled out and finished in the traditional style of sculpting, putting in pore texture and wrinkles, and made a mold of that. Then we fit it around an articulated skeletal structure and all of the mechanics that will operate the head, and all of that was sealed up with a flesh-like silicone skin.” The finished puppet requires seven technicians and 12 feet of cable to operate.

Pointing to the gruesome puppet and its breathing mechanism that causes it to swell rhythmically, Rosengrant remarks with parental pride, “It’s horrible, isn’t it?”

From this model, which appeared in the film in close-ups, and other demon models designed and constructed at Stan Winston, Craig Hayes’ team at Tippett Studio reproduced a writhing horde. “We scanned them to create computer replicas, painted them, and then put them into performance action, flying or running, jumping over cars,” Hayes offers. “At one point in the film the air is dense with demons.”

Costumes, Makeup and Stunts

Much as the landscape of hell is a hostile and deteriorated version of our own world, its inhabitants look as they did the moment they crossed over, but similarly degenerated.

Costume designer Louise Frogley (Spy Game, Traffic) offers “Francis’ concept that they die in whatever they were wearing and get grunged up in hell. As there is no water there, clothing gets dirty, dry and caked, as do the people themselves.” To achieve this look, she and costume supervisor Robert Q. Mathews had everything “stone-washed to get the newness out and then aged by our textiles staff by applying cheesecloth, yak hair, some polyester batting and liquid latex. They applied different types of dust and dirt and finally put it all through a severe drying process that, altogether, took 48 hours from start to finish for each article of clothing.”

Frogley avoids the concept of palettes in favor of suiting individual characters, zeroing in on the substance of each with a brainstorming approach. “Midnite is very colorful and flashy, Chaz is youthful and relaxed, Rachel needed an athletic and professional look, sexy but not overtly. Constantine is classic, cool, black and white, serious, linear, straight-edged.”

Acknowledging the strong film-noir elements in Constantine’s look and manner, she “was also somewhat influenced by English 1960s fashion and copied a raincoat for him from that period. The overall look is compact and slim, which enables him to move with his customary grace.” Considering the physical demands of the role, not to mention the amount of scenes that involve rain or water, Frogley kept a total of 25 duplicate coats on hand for Keanu Reeves, as well as 50 pairs of shoes.

For Gabriel’s entrance, Frogley prepared a richly tailored ensemble, which Swinton herself calls “the Sotheby’s rep look,” adding, “of course, I also have a beautiful set of wings. Every girl should have one.”

Frogley and her team, in collaboration with Stan Winston Studios, also created clothing for a loathsome entity the crew came to call Vermin Man – a demon in loosely human form who attacks Constantine on the street before exploding into his component parts which are largely snakes, roaches and scorpions. As Frogley recalls, “Mike Fink had the idea that the cloth consisted of termites. It took months with our textile artist, Marietta Lange, to develop samples for Mike and Francis.

Eventually we came up with something made of fleece, cheesecloth and wool, with sequins, beads, feathers, hair and toy insects.” Her candid evaluation of the final product? “It was completely revolting.”

Complementing Frogley’s efforts and also working in tandem with the visual effects team and the Stan Winston crew in particular, was renowned makeup artist and multiple Academy Award winner Ve Neill (Beetlejuice, Mrs. Doubtfire, Ed Wood). Leading a team of up to 15 makeup artists at any given time, Neill’s work ran the gamut from the subtle to the nightmarish, preparing human, half-breed and demon alike for various battles, as well as helping to reveal the effects of the advanced illness Constantine tries to hide behind a wall of action and attitude.

The climactic confrontation in the hydrotherapy room at Ravenscar Hospital between Constantine and Chaz against a multitude of demon half-breeds was a colossal undertaking for cast and crew alike. Beginning at 3:00 AM, stunt men and women reported to the set for their makeup and prosthetics.

Additionally, a roomful of actors portraying half-breeds were prepared for the moment when their counterfeit visages would melt away to reveal their demon features.

Regarding the progression of Constantine’s terminal lung cancer, Neill notes that the low-lighted sets “cast a kind of pale yellow-green tone onto the walls, which adds to the makeup in making him appear very sallow and ill.” Exercising restraint throughout, Neill avoided “making Keanu look too terrible in the beginning because we’d have no place to go, so I just tried to keep him slightly on the unhealthy side.” Towards the end, “not only because of the illness but also the pounding he takes from all these fights, we start seeing a bit more degeneration, more trauma and fatigue, so there are slight changes in his makeup.”

“A demon just attacked me on Figueroa, right out in the open.” – John Constantine

“One of the story’s motifs is about knocking the hero down and seeing if he can get back up,” Reeves offers wryly, on the physical aspects of the role. “Each time, you can feel Constantine thinking ‘OK, right, here we go again.’ Throughout the film I get choked, throttled, smashed and generally kicked around. It’s really been good fun.”

Constantine reunites Reeves with renowned stunt coordinator R. A. Rondell, who worked extensively with him on the groundbreaking action sequences for The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions, and who goes as far back as 1991 with him on Point Break. The level of trust and admiration Reeves feels for Rondell and his team cannot be overstated. Conversely, says Rondell, citing the actor’s natural athleticism and killer work ethic, “Keanu’s level of participation is very high and very consistent. For a stunt coordinator, that’s a godsend. We pretty much take it to the limit with him in terms of what we can do with an actor.”

The more action he can authentically execute on screen, Reeves feels, the better the overall performance. “Instead of having to cut away it allows me to stay close in the situations of peril, and it helps the audience stay and hopefully feel and connect with the character.”

For John Constantine, peril lurks behind every door: from violent exorcisms to old-fashioned fist fights with demons, not to mention being blown clear across the room and upside down like a cotton ball from a puff of Gabriel’s powerful breath.

The film’s single most complex and kinetic fight sequence is a battle pitting Constantine and Chaz against a legion of half-breed demons in a room at the Ravenscar Hospital. Already a logistical puzzle for stunts and wire work because of low ceilings and tight space, it was made all the more challenging because of the number of combatants involved, and because Francis Lawrence wanted to film it in one continuous shot – a stylistic choice Rondell was the first to support. “We were going for an even flow, a nice cadence without breaking up the action,” he says. Ultimately the shot involved nearly a dozen stunt actors flying through the air while others lunged and fought simultaneously below them and Lawrence got the uninterrupted current he envisioned.

As the intrepid Angela, Rachel Weisz drew her fair share of danger. Held underwater by Reeves for a crucial scene, she struggles wildly to free herself. Deceptively simple, Rondell cautions that such a scene could easily prove deadly if those on set mistake acting for genuine survival. A lot depended upon pre-arranged signals and Reeves’ instinct. Later, in a scene where Angela fights for her life in the hospital hydrotherapy pool, Weisz reveals good-naturedly, “I went under and whacked my head on the bottom. By the time we had finished all the water scenes I was bruised and scraped and sore for weeks. Luckily, nothing broken.”

Even Shia LaBeouf got in on the genuine action, in his big fight with the half-breeds, as Rondell relates. “We put him on a cable and flung him right up into the ceiling, then dropped him to the floor. It was great. We went through it first with a stunt double, and prepared both the ceiling and floor to be soft, then put him through it. It looks like a million bucks when you see the actor take a slam like that and you know it’s really him.”

But Rondell didn’t stop there. He wasn’t satisfied until he got the director himself strapped into a harness for a bird’s eye view of his set. “It wasn’t for a stunt,” Lawrence modestly clarifies. “I just rode the path of the camera to see the action from a high vantage point, the way a dolly moves. They brought me up on cables and sort of slid me across the room. It was great fun.”

From the bottles of holy water Constantine keeps in a defensive ring around his apartment, to amulets and the myriad individual bits and pieces of religious artifacts he uses for power and protection, Constantine utilizes an ever-changing idiosyncratic arsenal of items to do his work and keep himself alive.

Most of these items are procured for him by his friend Beeman, through circuitous barter with a maze of clandestine agents around the world. Beeman, the master historian and scholar, is able to lay his hands on such enticing artifacts as stone fragments from the road to Damascus; bullet shavings from an assassination attempt on the Pope; a screech beetle from Amityville; a piece of Moses’ shroud; numerous crosses and other religious icons blessed by high-ranking clergy throughout the ages; and, perhaps the most inexplicable, a vial of highly flammable dragon’s breath, which produces a ten-foot flare of searing heat like a flame-thrower.

As the production’s real-life Beeman, property master Kirk Corwin created this incomparable assortment by more conventional means, but still relied upon extensive historical research, as well as immersion in classical Latin, as nearly every important item featured a Latin inscription.

Corwin is understandably most proud of the collection’s showpiece: Constantine’s holy shotgun, a weapon presumably crafted from a crucifix with a hollow shaft, adapted into a deadly firearm, the blast from which can vaporize the foulest demons and send them back to hell.

By far the most complicated prop in the film, the shotgun had to fire multiple rounds while having a look in keeping with Beeman’s other relics. Corwin started by examining existing shotguns. Finding one called a “Street Sweeper” that would serve as an excellent model, he worked with Lawrence and Shohan to refine its look. They decided that the components of the gun should appear to be based upon drawings by Leonardo Da Vinci.

Once designed, the prop master still had to put it all together and end up with a functional firearm. He would eventually make two guns that actually fired, two picture-perfect plastic replicas plus four rubber versions for rehearsals and use by stand-ins. Eight craftsmen took more than seven weeks to produce the two working models. The final result is a gleaming and fearsome weapon made of brass and gold, etched with the Latin phrases “a cruce salus” (“from the cross comes salvation”), “decus it tutamen” (“an adornment and a means of salvation”) and “dei gratia” (“by the grace of God”).

Keanu Reeves was so impressed with the polished piece that he ordered an additional shotgun to be made as a gift for Frances Lawrence upon completion of principal photography.

Production notes provided by Warner Bros. Pictures

Constantine

Starring: Keanu Reeves, Rachel Weisz, Max Baker, Djimon Hounsou, Tilda Swinton, Peter Stormare

Directed by: Francis Lawrence

Screenplay by: Kevin Brodbin, Mark Bomback, Frank Cappello

Release Date: February 18th, 2005

MPAA Rating: R for violence and demonic images.

Studio: Warner Bros. Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $75,976,178 (32.9%)

Foreign: $154,908,550 (67.1%)

Totol: $230,884,728 (Worldwioe)