Acclaimed director Tim Burton brings his vividly imaginative style to the beloved Roald Dahl classic Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, about eccentric chocolatier Willy Wonka (Johnny Depp) and Charlie Bucket (Freddie Highmore), a good-hearted boy from a poor family who lives in the shadow of Wonka’s extraordinary factory.

Most nights in the Bucket home, dinner is a watered-down bowl of cabbage soup, which young Charlie gladly shares with his mother (Helena Bonham Carter) and father (Noah Taylor) and both pairs of grandparents. Theirs is a tiny, tumbledown, drafty old house but it is filled with love. Every night, the last thing Charlie sees from his window is the great factory, and he drifts off to sleep dreaming about what might be inside.

For nearly fifteen years, no one has seen a single worker going in or coming out of the factory, or caught a glimpse of Willy Wonka himself, yet, mysteriously, great quantities of chocolate are still being made and shipped to shops all over the world.

One day Willy Wonka makes a momentous announcement. He will open his famous factory and reveal “all of its secrets and magic” to five lucky children who find golden tickets hidden inside five randomly selected Wonka chocolate bars. Nothing would make Charlie’s family happier than to see him win but the odds are very much against him as they can only afford to buy one chocolate bar a year, for his birthday.

Indeed, one by one, news breaks around the world about the children finding golden tickets and Charlie’s hope grows dimmer. First there is gluttonous Augustus Gloop, who thinks of nothing but stuffing sweets into his mouth all day, followed by spoiled Veruca Salt, who throws fits if her father doesn’t buy her everything she wants. Next comes Violet Beauregarde, a champion gum chewer who cares only for the trophies in her display case, and finally surly Mike Teavee, who’s always showing off how much smarter he is than everyone else.

But then, something wonderful happens. Charlie finds some money on the snowy street and takes it to the nearest store for a Wonka Whipple-Scrumptious Fudgemallow Delight, thinking only of how hungry he is and how good it will taste. There, under the wrapper is a flash of gold. It’s the last ticket. Charlie is going to the factory! His Grandpa Joe (David Kelly) is so excited by the news that he springs out of bed as if suddenly years younger, remembering a happier time when he used to work in the factory, before Willy Wonka closed its gates to the town forever. The family decides that Grandpa Joe should be the one to accompany Charlie on this once-in-a-lifetime adventure.

Once inside, Charlie is dazzled by one amazing sight after another. Wondrous gleaming contraptions of Wonka’s own invention churn, pop and whistle, producing ever new and different edible delights. Crews of merry Oompa-Loompas mine mountains of fudge beside a frothy chocolate waterfall or ride a translucent, spun-sugar, dragon-headed boat down a chocolate river past crops of twisted candy cane trees and edible mint-sugar grass. Marshmallow cherry creams grow on shrubs, ripe and sweet. Elsewhere, a hundred trained squirrels on a hundred tiny stools shell nuts for chocolate bars faster than any machine and Wonka himself pilots an impossible glass elevator that rockets sideways, slantways and every which way you can think of through the vast and fantastic factory.

Almost as intriguing as his fanciful inventions is Willy Wonka himself, a gracious but most unconventional host. He thinks about almost nothing but candy – except, every once in a while, when he suddenly seems to be thinking about something that happened long ago, that he can’t quite talk about. It’s been said that Wonka hasn’t stepped outside the factory for years. Who he truly is and why he has devoted his life to making sweets Charlie can only guess.

Meanwhile, the other children prove to be a rotten bunch, so consumed with themselves that they scarcely appreciate the wonder of Wonka’s creations. One by one, their greedy, spoiled, mean-spirited or know-it-all personalities lead them into all kinds of trouble that force them off the tour before it’s even finished.

When only little Charlie Bucket is left, Willy Wonka reveals the final secret, the absolute grandest prize of all: the keys to the factory itself. Long isolated from his own family, Wonka feels it is time to find an heir to his candy empire, someone he can trust to carry on with his life’s work and so he devised this elaborate contest to select that one special child. What he never expects is that his act of immeasurable generosity might bring him an even more valuable gift in return.

Bringing Roald Dahl’s Classic Story to the Screen

In bringing Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to life on screen, producers Brad Grey and Richard Zanuck had some small idea of what they were getting themselves into. “This was bigger than anything I’ve been involved with in my entire career, not only as a producer but as a studio head. It’s bigger in scope, size and imagination,” says Zanuck, an Oscar winner for Driving Miss Daisy and 1991 recipient of the Academy’s Thalberg Award.

“Here was a book with the potential, just visually, to be absolutely spectacular on film and we were excited with the idea of being able to produce it on a scale that Roald would have appreciated, without compromising any of the heart he put into it,” says Grey, currently Chairman and CEO of Paramount Pictures Motion Picture Group and a four time recipient of the prestigious George Foster Peabody Award, as well as an Emmy and Golden Globe winner for The Sopranos and a 17-time Emmy nominee during his career as an independent producer. “We took our time to get the script right and assemble a team that felt the same way we did about it.”

The filmmakers also sought the support and collaboration of Felicity Dahl, Roald’s wife and the caretaker of his estate since his death in 1990. Says Grey, “Without her blessing, we wouldn’t have a movie.”

Dahl, an executive producer on the film, acknowledges the scale of the undertaking. “An adaptation like this is daunting because I don’t think there’s a child in this world who hasn’t read the story or knows about it. Every child wants to be Charlie.” Delighted at how the creative team came together and how Roald’s original images were interpreted on a grand scale, she calls it, “the ideal combination: Roald Dahl, Johnny Depp and Tim Burton, absolutely unbeatable and completely in sync.”

Published in 1964, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory recently celebrated its 40th anniversary in print. As beloved by children and adults today as it has been throughout the past four decades, the book has sold over 13 million copies worldwide and been translated into 32 languages. Its enduring popularity indicates how well the author understood, appreciated and communicated to children. As Grey observes, “He never talked down to his readers or underestimated their intelligence.”

Johnny Depp, who stars as Willy Wonka, especially appreciates, “the unexpected twists in Dahl’s writing. You think it’s going in one direction and then it slams you with another alternative, another route, and makes you think. At its center, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is a great morality tale. But there’s also a lot of magic and fun.”

Although hugely popular with children, the consensus of the book’s adult fans is that, most definitely, “it’s more than a children’s book,” says Zanuck. “It’s a wild ride, certainly, a fun-house candy fantasyland, but it has deeper emotional implications. The character of Wonka, who he is and who he becomes at the end of the story through his connection with young Charlie, is very moving. It’s a fantasy that touches everyone.”

When it came time to select a director, Tim Burton was ideal choice. “When you look at his body of work, there’s a running theme of intelligence and whimsy that’s perfectly suited for a story like this,” says Grey. “Like Dahl, he never underestimates the sophistication of his audience. In our first conversations it was clear that Tim was a fan and wanted to be as faithful to the book as possible, which was right in sync with how we felt.”

“One of the interesting aspects of the book is that it’s so vivid in mood and feeling and so specific, yet it still leaves room for interpretation,” Burton believes. “It leaves room for your own imagination, which, I think, is one of Dahl’s strengths as a storyteller.

“Some adults forget what it was like to be a kid. Roald didn’t,” Burton continues. “So you have characters that remind you of people in your own life and kids you went to school with, but at the same time it harkens back to age-old archetypes of mythology and fairy tales. It’s a mix of emotion and humor and adventure that’s absolutely timeless and I think that’s why it stays with you. He remembers vividly what it was like to be that age but he also layers his work with an adult perspective. That’s why you can revisit this book at any time and get different things from it no matter what your age.”

Burton worked previously with Felicity Dahl when he produced the 1996 animated fantasy adventure James and the Giant Peach, adapted from another of Roald’s books, and she was pleased when he committed to Charlie. She sees in him some reflections of her late husband’s unique “creativity and sense of humor,” adding that, “I wish Roald was here to work on it with Tim, because they would have been brilliant together.”

“What we have,” says Zanuck,” is a blending of these two genius minds. Tim has gone back to the specifics of the author’s intent and given his own extraordinary spin to it.”

Early in pre-production, Burton visited the Dahl home and looked inside the spare, unheated workroom where Roald did all of his writing. Away from the noise and bustle of the house, it was his private no-frills sanctuary. Burton was amazed to realize how closely his designs for Charlie Bucket’s ramshackle house resembled this structure and Felicity Dahl confirmed it was very likely the author’s inspiration for the Bucket home.

Moved by the experience, Burton says, “It made me feel like we were definitely on the same wavelength. It was uncanny how similar the two structures were. Roald even used rolled-up pieces of cardboard to prop together a makeshift desk for himself. I never had the opportunity to meet the man, but just through the work I feel some kind of connection with him.”

Screenwriter John August (Big Fish) has his own special connection with Roald Dahl. “When I was in the third grade,” he recalls, “we had to write a letter to a famous person. Nearly everyone chose Jimmy Carter, who was the president then, but I chose Roald Dahl because my favorite book was Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Incredibly, I got back a postcard from him, from England. I was ten years old and it was my first contact with an author. That was one of the things that inspired me to become a writer. So it was a great honor and responsibility for me to adapt this book into a movie.”

What touches August most about the story is that, “even though Charlie is very poor, and he doesn’t have much to eat, he lives in a little house with all of the people that he loves – mother, father, and both sets of grandparents. That’s a remarkable gift that any kid would be lucky to have.”

Taking his cue both from the book and the filmmakers, August maintained the story’s non-specific time or place. “It’s timeless,” states Grey. “It doesn’t matter if it’s today or 40 years ago. A message that suggests being true to yourself and to other people, and treating others as you would like to be treated – the golden rule – is never outdated.”

Burton and August added a nuance to the Wonka character by offering a glimpse into his own childhood. In flashbacks, while the children, accompanied by one parent each (or in Charlie’s case, his grandfather) tour the factory, Willy revisits crucial moments from his past and remembers conversations with his own stern father, town dentist Dr. Wilbur Wonka. We see the overly protective Wonka Sr. forbid his son to eat sweets, and imagine how young Willy’s unrequited longing for a taste of chocolate became a lifelong fascination that grew into the Wonka candy empire.

“Where the book allows room for possibility and the reader’s interpretation,” explains Burton, “we felt the film needed to provide some framework in the case of Wonka’s eccentricity, to offer some possibility of why he is the way he is without delving too deeply into it.”

Felicity Dahl concurs, noting that, “all books have to be changed a bit in making a film. The important thing is that the alterations enhance the story rather than detract from it, and I believe that’s what Tim has done here. When you choose someone like Tim to make a film, you choose him for his creative ability so you have to give him your trust.”

During the tour, Charlie’s innocent question about whether or not Wonka remembers his first taste of candy stirs deeply buried feelings in the famous chocolatier. When he later offers Charlie the grandest prize of all – the factory itself with all its wonders – and Charlie refuses to accept if it means leaving his family behind, it gives Wonka pause. Maybe he’s underestimated the value of family. Maybe Charlie, who is always a little hungry and lives in a broken-down hovel, has something better than money and chocolate.

“It’s a beautifully simple message, in this world where people are always striving after material things and success,” says Burton. “There are material things and then there are the emotional and spiritual. Sometimes the most important things are the simplest.”

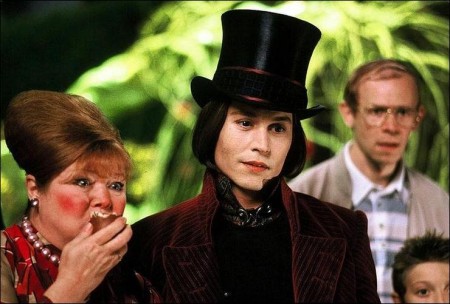

Casting Willy Wonka, Charlie Bucket, Bucket Family

When Tim Burton proposed the role of Willy Wonka to his friend and frequent collaborator, two-time Oscar nominee Johnny Depp, he was barely able to get the words out. As Depp relates the conversation, “We were having dinner and he said, `I want to talk to you about something. You know that story, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory? Well, I’m going to do it and I’m wondering if you’d want to play….’ and I couldn’t even wait for him to finish the sentence. I said, `I’m in. Absolutely. I’m there.’ No question about it.”

“To be chosen to play Willy Wonka in itself a great honor,” says Depp, a long-time fan of Dahl’s work, “but to be chosen by Tim Burton is double, triple the honor. His vision is always amazing, beyond anything you expect. Just the fact that he was involved meant I didn’t need to see a script before committing. If Tim wanted to shoot 18 million feet of film of me staring into a light bulb and I couldn’t blink for three months, I’d do it.”

Before long the two were poring over Burton’s preliminary sketches, discussing Wonka’s look and the themes of the story, falling into a familiar creative rhythm that began when the director cast Depp as the lead in the 1990 poignant fantasy Edward Scissorhands. They subsequently re-teamed for the critically acclaimed Ed Wood and Sleepy Hollow and are currently working together on the stop-motion animated feature Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride.

“Johnny is a great character actor in many ways,” says Burton – “a character actor in the form of a leading man. That’s what struck me about him from the very beginning and it’s what makes him such an intriguing actor – the fact that he’s not necessarily interested in his image but more in becoming a character and trying different things. He’s willing to take risks. Each time I work with him he’s something different.”

“He’s a tremendously insightful actor,” adds Grey. “He came to the project with respect for the book and also a sense of how he could do something very special with this character. I can’t think of anyone we’d rather have in the role. Sometimes the right magical combination comes together and I believe that’s what we have here: Roald, Tim, and Johnny.”

Above all, Depp approached the role with “a great sense of affection for Wonka.” Forced to open his beloved factory for the first time in 15 years to find an heir, Wonka is uncomfortable with the unfamiliar human contact. As Depp suggests, “he puts on his game face in front of people but underneath he has a great anxiety about actual contact or closeness. I believe he’s a germophobe, which is why he wears gloves, and in addition to the gloves it’s as if he’s wearing a mask. There are moments during the tour when we catch Wonka acting, and acting badly, literally reading off cue cards. I don’t think he really wants to spend any time with these people. I think he’s struggling, from the first second, to put on an act for them and keep a smile.

“At the same time,” Depp continues, “a part of him is genuinely excited about being the grand showman, like P.T. Barnum, pointing out everything he’s created and saying, `hey, look at this! Look what I’ve done, isn’t this wonderful?’”

“Willy Wonka is an eccentric,” notes Zanuck. “He’s odd, he’s funny, he’s aloof yet terribly vulnerable; it’s an interesting composite, both childlike and deep at the same time. No other actor could give this character the kind of depth, range and spin it requires. Johnny has an incredible gift.”

Burton and Depp worked with Academy Award-winning costume designer Gabriella Pescucci (The Age of Innocence, Van Helsing) to arrive at precisely the right look for Wonka, which resulted in a total of 10 different plush jackets and overcoats. In keeping with the timeless quality of Dahl’s tale, wardrobe was, Pescucci says, “contemporary, but with some old-world styling.”

Regarding Wonka’s hair and other small but significant details, Depp made some deliberate choices. “The hair was one of those elements I saw clearly very early on,” he says. “The top hat was easy, because that came right from the Quentin Blake drawings, but the hair I imagined as a kind of Prince Valiant do, high bangs and a bob, extreme and very unflattering but something that Wonka probably thinks is cool because he’s been locked away for such a long time and doesn’t know any better, like the slang he uses.”

Based on the book’s description of Wonka’s sparkling eyes, Depp selected a pair of violet-tinted contact lenses for an effective dimension of color, and drawing from the story of Wonka’s childhood orthodontia, decided he should flash remarkably perfect teeth. Add to that a distinctly pale skin tone from years of living indoors and an image of Wonka emerges as an extraordinary figure of outlandish but expensive tastes, with a style of speech and presentation as unique as his lifestyle…

Starring as Charlie is Freddie Highmore, who rejoins Depp after sharing the screen with him in 2004’s acclaimed drama Finding Neverland. Twelve years old when Charlie began production, Highmore had already carried leading roles in the family films Five Children and It and Two Brothers, and portrayed young King Arthur in the TNT miniseries The Mists of Avalon.

As Grey attests, “He brings great emotion to the role, but you don’t see any of the strings – you don’t see him working. He really is well beyond his years to have that kind of skill.”

Expressing the consensus of opinion from all who have worked with him, Burton marvels at how “completely natural and genuine” the young actor is. “He has such gravity, without ever being false, which is very difficult to do, even for an adult actor. He has the ability to convey emotion without speaking or trying too hard. That’s not something that a director can tell someone to do; they either have it or they don’t. This is why casting Charlie was crucial.”

To Highmore, Charlie’s appeal is based on his being “a normal boy. He doesn’t have any special talents or superior qualities. In fact, he doesn’t have much of anything at all, except for his family, but he’s always thoughtful and really nice to everyone. So when his wish comes true and he goes to the factory, I think people are happy for him because he’s so deserving.”

In that respect, says Zanuck, “Freddie conveys an air of purity and goodness” – yet, he doesn’t take it too far. “Goodness can be so boring on screen,” quips Helena Bonham Carter, who first worked with Highmore in the 1999 British comedy Women Talking Dirty. “Essentially, Charlie’s a good soul with the right values. He’s not spoiled, which sets him apart from the other four children. But what’s great about Freddie is that he doesn’t make Charlie a drippy boy, which is always the danger with a role like this.”

As Charlie’s home is dominated by the Wonka factory looming just behind it, so his imagination is dominated by thoughts of what might be inside. Still, unlike his privileged companions on the tour, he is content with his life as it is. Says Highmore, “Even though he has cabbage soup every night and wears a sweater that’s threadbare, Charlie has a loving family. He seems to have nothing, but he’s actually got everything already.”

When Charlie comes home with the precious golden ticket it revitalizes old Grandpa Joe, played by Waking Ned Devine’s David Kelly. “You can see it in his walk, you can see it in his talk,” says Zanuck. “Grandpa Joe used to work in the factory years ago before Wonka shut the town out, and those were his glory days. The opportunity to get back into the factory literally gets him out of bed and makes him come alive again.”

“When David walked in, that was it,” Burton recalls. “He was Grandpa Joe. What an amazing actor, and what a deeply expressive face, like a silent movie character.”

Kelly appreciates how Dahl highlighted the special relationship between Charlie and his grandfather, noting that the author saw value in the whole spectrum of age. Not having had the good fortune to know his own grandparents, who died before he was born, the actor enjoys the connection his children have with his parents, and asks, “Is there anybody in the world who doesn’t feel a very special grace for their grandparents?”

Kelly compares the production to “being inside Tim Burton’s head, which is a rewarding place to be. The man is a standard-setter, truly brilliant. When people asked what I did, I’d say `well, I was being rowed by 50 Oompa-Loompas in a pink candy boat down a chocolate river with Johnny Depp.’ The sets are wonderful – hand-painted, handmade, the kind you rarely see anymore. Going to work every day was endlessly jaw-dropping and magical.”

Cast as Charlie’s loving parents are Helena Bonham Carter and Noah Taylor, both of whom, says Burton, “shine in relatively small roles that bring warmth and credibility to Charlie’s family unit. The house and their living conditions are so extreme, almost surreal, that without the right actors it just wouldn’t have worked. We were lucky to have Noah and Helena; they truly made it feel like a real family.”

Bonham Carter, whose starring role in the 1997 romantic drama The Wings of the Dove earned both Oscar and BAFTA nominations, describes the emotional balance she and Taylor keep as Mother and Father Bucket. “Like Grandpa Joe,” she says, “Charlie’s parents are accustomed to disappointment. We’ve had a hard time with life, used to being the underdogs, so when the golden ticket contest is announced of course we haven’t the slightest expectation that Charlie has a chance of winning. The odds are tiny. We adore our son and don’t want him to be hurt so we try not to get his hopes up. He’s always been our main source of joy but when he finds the ticket, suddenly, he becomes the embodiment of hope and life and future for the whole family.”

Taylor (Shine, Almost Famous, The Life Aquatic) sees Mr. Bucket as “not the kind of man you’d call successful. He’s probably from a long line of people who aren’t particularly rich or clever or well-connected, but he’s clever enough to keep his family together and bring up a sweet child, and that, I think, is one of the greater accomplishments you can have in life.”

For Taylor, Dahl’s message, as illustrated by the Bucket family, is that, “you don’t need money or status to be a good person.” Yet, “it’s not the sort of moral that’s thrust down your throat; rather, he allows you to discover it for yourself.”

The Four Rotten Children

Cast as the four children who join Charlie on the factory tour are AnnaSophia Robb as Violet Beauregarde, Jordan Fry as Mike Teavee, Julia Winter as Veruca Salt and Philip Wiegratz as Augustus Gloop. Like their fictional counterparts who vie for a Golden Ticket to Wonka’s factory in a global contest, the four talented young actors of varying backgrounds and experience were chosen from an international pool.

We’re not saying they’re bad, these four Golden Ticket winners, but as Zanuck diplomatically puts it, “they’re not the kind of children you’d be proud to call your own.”

Violet Beauregarde is a ferociously competitive and self-assured little hellion who boasts f a roomful of trophies back home and is currently working on the world’s record for non-stop gum-chewing. Ignoring Wonka’s warning, she seizes a piece of experimental chewing gum with a blueberry flavor from the Inventing Room and within moments is turned blue and blows up like a giant blueberry-hued beach ball and must be removed to the Juicing Room. Violet is played by 11-year-old American AnnaSophia Robb, who recently starred in Wayne Wang’s family feature Because of Winn-Dixie and The WB’s 2004 television movie Samantha: An American Girl Holiday.

Robb says her Charlie experience “made me feel like a little part of history because everyone loves the book so much. Being on set was like a fantasy too, having a rooms full of candy that you get to play in and eat. Really cool.” Her preparation for the role included martial arts training with teacher and stunt professional Eunice Huthart, for an introductory scene in which Violet is seen mercilessly knocking down her rivals in a karate competition.

Know-it-all video game addict Mike Teavee, played by 12-year-old American Jordan Fry, scoffs rudely at another of Wonka’s inventions, an attempt to transport a chocolate bar via electromagnetic waves through a television screen. Teavee interrupts the experiment by inserting himself into the middle of it with some very unexpected results.

Newcomer Fry happily found himself flying across the set on wires for the sequence. “The hardest part,” declares stunt coordinator Jim Dowdall, “was keeping him from laughing in sheer delight at the experience because in the scene he’s supposed to appear rather frightened and unsettled.”

Gluttonous Augustus Gloop is unable to resist the lure of the factory’s luscious chocolate river and breaks from the tour to get taste of it, despite cautions from his mother and Wonka. He promptly falls in, mouth-first, and is sucked up through an intake pipe that transports the chocolate to other parts of the factory.

Meanwhile, hopelessly spoiled Veruca Salt has problems of her own. Upon seeing Wonka’s squirrels at work in the nut room she demands to have one and storms the assembly line. The squirrels examine her as they evaluate all nuts, determine she is a bad nut and dispatch her down the garbage chute with the other rejects. Veruca is played by 12-year-old Londoner Julia Winter, a member of the children’s drama group Allsorts Drama, in her professional acting debut.

“I couldn’t get the hang of lying on the floor fighting off the squirrels so Tim lay down on the floor next to me and demonstrated,” Winter offers. “There we were, both of us, kicking our legs and screaming at the top of our lungs, swatting away imaginary squirrels. It was great fun and we must have looked absolutely ridiculous.”

The parents of these beastly children represent the worst imaginable child-rearing skills, hilariously evident as they chaperone their horrible little brats through the factory.

Missi Pyle (Big Fish, Dodgeball, Bringing Down the House) as Mrs. Beauregarde appears more manager and coach than mother to young Violet, an obnoxious girl bent on winning every conceivable prize and contest in the world. “Mrs. Beauregarde wants her daughter to have everything she didn’t,” says Pyle. “A self-proclaimed winner, she has instilled in Violet her own competitive sprit to the exclusion of any other thought. The two of them arrive at the factory – in matching outfits, of course – fully expecting to go home with the grand prize,” whatever it may be.

Veteran actor of both film and television, BAFTA Award nominee James Fox (A Passage to India) stars as the beleaguered Mr. Salt, father to the colossally spoiled Veruca, a girl with no thought for anyone or anything but herself. “He’s very anxious that his daughter have everything she wants,” says Fox, who slyly describes Veruca Salt as “lovable, adorable, sweet and talented, the perfect child,” before adding, “as long as her father meets her demands. Immediately. If he doesn’t, she’ll scream until he does.”

Fox believes the tour ultimately proves beneficial for all the children. The lessons meted out to the rude, selfish and inconsiderate are quite valuable, “and Wonka serves somewhat as a judge. He discerns the children’s motives and their characters and he wants to change and correct them. He wants to make them better people.”

Adam Godley (Love Actually, Around the World in 80 Days) as Mr. Teavee and Franziska Troegner (nominated for the German Film Award in her native country for 2001’s Heidi M) as Mrs. Gloop fare no better. Mr. Teavee is sadly not immune to his son’s sarcastic bullying and poor Mrs. Gloop seems not only unable, but uninterested in controlling Augustus’ rampant gorging.

The Oompa-Loompas and Dr. Wonka

Deep Roy, whom Burton appropriately calls “the hardest-working man in show business,” took on the daunting task of starring as an entire community of Oompa-Loompas, the factory’s sole work force. Rescued by Willy Wonka from their harsh life in distant Loompaland, they now cheerfully live and work inside its walls and feast on their favorite food: cocoa beans.

Having worked with Burton in Planet of the Apes and Big Fish, Roy was happy to renew the association when contacted about the part. But there was a catch, as the actor relates with a laugh. “The first time Tim mentioned the idea he said `There will be only one Oompa-Loompa and it’s going to be you. We’re going to create hundreds from you.’ Then he thought perhaps I would be doing as many as five in close-up. The next time I saw him in London, five had become nineteen! In the end, it didn’t matter to me if it was 19 or 20 or 50. It’s been an absolute blast.”

The production team managed to populate the screen with scores of the diminutive and industrious factory workers through motion and facial capture technology, creating duplicate yet individual Oompa-Loompas in computer image from Roy’s multiple performances and then scaling them down to size. For Roy, it meant months of rehearsal and choreography. If a scene called for numerous Oompas to join in a narrative song and dance, Roy would perform the steps for all of them, each from a slightly different starting mark and each with subtle distinctions of expression and movement, so that when the images were joined he became an entire troupe.

“The audience may think it’s all computer-generated,” says Roy, “but that’s not the case. If you see 20 Oompas, I did all 20 performances.”

Additionally, state-of-the-art photo-realistic and animatronic Oompas were modeled from Roy to supplement the action and serve as physical focal points in the scenes.

“Deep did a heroic amount of work on this,” Burton acknowledges. “Considering how to present the Oompa-Loompas there were a number of possibilities, one of which was full computer animation, but I think this was the way to go, to give it that important human element and keep it true to the spirit of the book.”

Bringing to life the role of Willy’s father, the dentist Dr. Wilbur Wonka, is Christopher Lee, conjured up by Willy’s memory in a series of flashbacks to his childhood. Well-respected worldwide, the British actor’s career spans nearly 60 years, first catching fire with the memorable Hammer horror films in the 1950s (of which Burton was an avid fan) and encompassing a wide range of feature and television productions including starring roles in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Star Wars sagas and 1998’s critically acclaimed Jinnah.

Lee sees the elder Wonka as “not a bad father, certainly, just overly stern and unable to show his love.” Dr. Wonka was acutely concerned with oral hygiene and overly protective of his son’s teeth, to the extent that he forbade the youngster from eating sweets. “It’s not exactly parental abuse,” Lee suggests, “as he does it for the best of motives. But he’s very strict and therefore comes across as a rather alarming figure to a little boy.”

“Not only is he a great actor, whose work I grew up watching and admiring,” says Burton, “but Christopher Lee is simply a powerful presence in every sense of the word.” As screenwriter John August avows, “He’s completely intimidating in just the right way.”

Lee, who worked with Burton and his Charlie co-star Johnny Depp on Sleepy Hollow and re-teams with them on the upcoming Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride, says, “Tim is a director of vast enthusiasm. It comes at you in waves of encouragement from behind the camera. He’s amazingly inventive and has a brilliant mind.”

In fact, Burton was so tirelessly active on the set and covered so much ground each day that Helena Bonham Carter gave him a pedometer as a joke. “She wanted to see how many steps he took in a day,” says Freddie Highmore, who cannot recall the official count but says “it turned out he didn’t need to go to the gym because he walks enough at work.”

Building Wonka’s World

Once inside the factory walls, offers Zanuck, “the children discover an entire world complete with a chocolate waterfall and chocolate river, edible trees and unbelievable machinery that only a mind such as Roald Dahl, interpreted by a mind such as Tim Burton, could possibly imagine. It’s fantasy, it’s fun, it’s completely outrageous and awe-inspiring. You don’t know where to look first.”

In creating the landscape of Wonka’s world, the filmmakers began at the source, to tap into, as Burton describes, “the textural, visceral quality of Dahl’s images and the scope. We tried to keep as true to the book as possible in creating specific places like the nut room and the TV room. Still, there is a lot of room for interpretation, which is the wonderful thing about doing an adaptation like this. Each room has its own flavor and possibilities.

“Instead of relying too much on blue or green screen effects we tried to build as much of the settings as possible,” the director continues. “We built most of the sets at 360 degrees so the actors are really enveloped in the environment.”

It was a huge compliment to the production when Felicity Dahl first stepped onto the Pinewood soundstages to examine the work in progress and enthusiastically declared, “it’s magical! I know that if Roald had seen it, he would have loved it. He would have said this is exactly what he had in mind.”

What Dahl had in mind proved no small task to construct. His Chocolate Factory contained cavernous rooms wherein whole environments were housed, like the one in which the Oompa-Loompas both worked and lived beside a chocolate waterfall and flowing chocolate river, where candy cane trees grew, giant peapods produced Wonka gobstoppers and even the grass was edible. Unwieldy one-of-a-kind machinery pumped out Wonka’s fanciful confections while in other rooms equally outlandish contraptions were engaged in experiments to create even more exotic and delicious candies. Traveling through the factory meant navigating the river in a translucent boat of spun pink sugar or climbing aboard a glass elevator that sped not only up and down but, as the text declares, “sideways and longways and slantways and any other way you can think of,” including blasting up through the roof at rocket speed.

Production utilized seven stages and much of the back lot at Pinewood Studios in the UK, including the famous James Bond stage, which houses one of the largest soundstage pools in the world. Says Production Designer Alex McDowell (Art Directors Guild Award winner for The Terminal and nominee for Minority Report; Fight Club, The Crow), “We pretty much took over the studio lot – lock, stock and barrel.”

Because Burton preferred to accomplish as much as possible with practical effects, a great deal of what appears on screen was created physically with prosthetic and special effects coordinated by Special Effects Supervisor Joss Williams, whose previous collaboration with Burton, Sleepy Hollow, earned him a BAFTA nomination. “When those reached their natural limitations, we took over in the digital realm,” says Visual Effects Supervisor Nick Davis (AFI and BAFTA nominee for Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone), who oversaw the integration of advanced motion capture technology and CGI “for anything that could not be achieved practically on set. It was a collaborative effort among multiple departments and it all began with Tim, who had all these ideas and kept producing drawings to show us what he wanted.”

Early pre-planning and ongoing communication were key, since images morphed instantly from one process to another and back again in the same scene. Sets were built and used simultaneously on the back lot, in the computer and in 24-scale miniature models. “I spent a lot of time in pre-production working with conceptual artists and Nick Davis, so that everything was cohesive,” says McDowell. “From a design standpoint, there’s no difference between a physical and a virtual set and Charlie was a film that required a total design sensibility, from Oompa- Loompa hand props to the vast CG world that the boat and elevator travel through.”

Citing the example of the spun-sugar boat, he says, “the boat travels from the chocolate river into a white tunnel rapids ride. It’s a physical entity in the chocolate room but inside the tunnel that’s a fully CG environment. The boat goes onto a gimbal platform and is shot against a blue screen. It also has to be replicated and made in CGI. You have actors in the physical boat with prosthetic Oompas and CG actors with scaled-down Oompa-size CG versions of Deep Roy at the oars in the CG boat. I spent a couple months in close collaboration with the CG and miniatures companies, designing alongside the 3D and physical model makers.”

The glass elevator posed design challenges of its own, as McDowell outlines. “It has to be self-supporting, with doors that open and close and it has to be strong enough to hang from a rig and crash through a set. It has to fly. But how to shoot it? How do you put a camera into a glass elevator?” Ultimately, adds Davis, “The elevator was a mixture of practical pieces on rigs or completely CG elevators with CG characters inside, depending upon the complexity of the shot. We used either hand-held cameras on cranes, with the actors inside, or motion control cameras where we could have the elevator moving up or falling 30 feet in the air. Sometimes it was actors standing on blue boxes and we added the elevator around them afterwards, in post.”

Issues of lighting the unusually vivid environment drew Oscar-winning cinematographer Philippe Rousselot (A River Runs Through It) into pre-planning discussions as well, as Davis describes. “Tim wanted vibrant lighting, primary colors. Turns out, bright and colored lights don’t mix well with chocolate. It was tough for us to keep the chocolate from turning grey or the boat from turning into a muddy mess. It was a real balancing act, to focus white light on some things while not detracting from the primary-colored walls and other props. Philippe and his team worked with us in pre-production and we worked out the lighting scheme one sequence at a time. Some of it could be done digitally and some had to be lamps on stage.”

The Chocolate River

“The most important thing Tim said about the chocolate river,” recalls Joss Williams, was “`make it look good enough to eat,’ and that’s how we approached it, to look as yummy as possible.”

For the effects supervisor, that meant managing “viscosity, looks, color testing and safety issues,” not to mention logistics, quantity, transportation and storage.

The option of making the chocolate off-site and bringing it in via tanker was quickly dismissed, as calculations estimated a need for 40 tanker trucks. It seemed a better plan to manufacture and store the stuff on site. As for mixing it, conventional cement mixers proved inadequate. They needed a vessel that could mix three or four tons at a time, which they found, ironically, in the form of commercial vats designed for mixing toothpaste, that could blend as many as 12 tons at a time and store 20,000.

Altogether, production required a constant supply of more than 200,000 gallons of flowing chocolate; approximately 32,000 for the waterfall and 170,000 for the river, which measures 180 feet long by 25-to-40-feet wide, and is nearly 3 feet at its deepest point.

Without revealing the exact recipe, Williams acknowledges experimenting with mixtures of water and dietary cellulose, with various food dyes to achieve the right look and texture. “Color to the eye is different than color on film,” he explains, “so we tested through a whole pattern of shades to get exactly the right one.” Once prepared, the mixture was constantly cleaned and tested daily by a local laboratory “to make sure it was safe for the company to work with and eat.” Only half-joking, he adds, “we had to keep the bugs down to an acceptable level. There’s about as many bugs in it as you’d find in an airline sandwich.”

For the scene in which Augustus Gloop tumbles into the chocolate river and is subsequently sucked up through an intake pipe to another part of the factory, young Philip Wiegratz was slowly conditioned to the unusual sensation of floundering in melted chocolate. “We started Philip in a small tank in the workshop” says Williams. “Then we tested him in the fat suit that he wears as Augustus; it couldn’t be too buoyant or he’d float, and it couldn’t absorb the mixture and become an enormous weight around him. Probably worst of all, from his perspective, was that once this stuff gets into your ears you can’t hear very well.”

As the scene progresses where the camera cannot follow, the practical set gives way to a CG rendering of events, with a virtual Gloop being squeezed into the narrow space and then spat upwards through the tube – all of which involved Nick Davis and his team with their own issues of color and viscosity, not to mention duplicating “liquid dynamics” in the computer.

Taking a big-picture approach, Davis maintains that, “software can help you break down the physics. You can plug in the known parameters – melt speeds, drip speeds, pour speeds, mass and weight, which helps a lot. But at the end of the day there’s always a human, artistic side to it, where you just look at it and say `hmmm, that’s too fast’ or `that’s too shiny.’”

The Oompa-Loompas

Bringing the Oompas to life involved the full cooperative effort of all the effects artists on the film, but it all began with one man, the Oompa-Loompa prototype: Deep Roy.

If five, six or 20 Oompa-Loompas appear in a scene, Roy played all of them. In separate takes, and from different starting marks, he would act out each single part on the motion capture stage, whereby his body and facial movements were recorded in the computer. If the scene was one in which the Oompa-Loompas join to dance and sing a number about the fate of each wayward child on the tour, the entire routine would be meticulously choreographed for months to composer Danny Elfman’s music. Then Roy would perform the steps from each individual spot on the line, subtly adjusting his gestures and expressions from one to the next so that when the collection of images were later joined together onscreen he would have created an entire troupe.

“I think of it as doing nineteen second takes,” offers Roy, whose extensive training for the roles included daily pilates sessions and dance classes. “The most challenging part was trying to remember my position from one performance to the next, counting in my head and remembering at what point to turn or where to look. It was a lot of rehearsing.”

“This was extremely tricky, partly just for the volume of shots it created,” says Chas Jarrett, Visual Effects Supervisor of The Moving Picture Company, one of the companies that joined the production team to work on Oompa-Loompa footage and contributed nearly 500 shots.

“Although effectively the Oompas look alike, we’ve slightly altered the facial tones of each. Their hairstyles may be a little different and each performance is slightly varied from one character to another.”

What the relatively new facial-capture process offers over standard animation, Jarrett believes, “is subtleties around the eyes and mouth shapes, the way the jaw moves and the skin stretches around the nostrils when he speaks. Those are the kinds of details that animators find most difficult to recreate. And here we get it free, with Deep’s performance.”

As if that wasn’t complicated enough, the Oompa-Loompas are only two-and-a-half feet high, so Deep Roy’s virtual image had to be proportionately reduced. This wouldn’t be a problem if he played his scenes solo but the Oompa-Loompas are in nearly every frame of the film and interact with all the human characters in various settings.

To illustrate how complicated it was just keeping track of the scale issue, Alex McDowell offers an impromptu checklist that sounds like one half of an Abbott and Costello routine: “Our environments had to be in two different scales. We had to be constantly aware of Oompa-Loompa scale, which is 30 inches high. Hand tools, controls, pathways and architecture had to conform to Oompa height. A lot of the time that’s Deep Roy, who is actually twice that height. So there’s Oompa scale and Deep Roy scale. Oompa scale is sometimes the same as human scale, with tiny props that stay tiny in human scale but appear larger in Deep Roy scale. Sometimes you have Deep sitting in a human chair so you build a double-size chair for him so he appears half-size to humans; sometimes Deep is in the Oompa environment in which case you build a set for Deep, at his scale, and a half-size set for Willy Wonka so that he appears large in the Oompa environment. The terminology alone is hard to get a handle on.”

Partly to provide a scale reference point in some scenes as well as a focal point and something for the actors to react to, the production enlisted animatronics and prosthetic makeup effects specialist Neal Scanlan, of Neal Scanlan Studio, an Oscar winner for his work on Babe. “Our goal,” says Scanlan, “was to make a photo-realistic Oompa-Loompa.”

He and his team assembled five completely motorized puppets, one for each room in the factory. Made from molds taken from an original sculpted model, the puppets were covered with painted silicone skin, hair-punched, and fitted with highly reflective blown-glass eyes. Their fiberglass skulls accommodated motors to realistically move their eyes and cheeks. Remotecontrolled rods beneath their chests turned and moved their heads, necks and limbs.

The creations were so lifelike that even Roy himself was taken aback upon first seeing them. “I was truly amazed,” the actor recalls. “They can talk, they can move their eyes and mouths. I thought, hey, am I going to lose my job here? Maybe they can just use the puppets.”

Another 15 puppets were designed full-bodied and pose-able but lacked internal mechanization and gained their illusion of motion through attachment to other moving props, such as the motorized oars on the spun-sugar boat.

The Squirrels

In his own fantastic yet logical fashion, Wonka understands that the world’s greatest experts on the quality of nutmeats are squirrels. No other creature on earth and certainly no man or machine could pick out good nuts from bad with such single-minded accuracy and speed.

So, as Wonka’s tour reaches the nut-sorting room the children see 100 of the captivating rodents perched on tiny stools, intently engaged in doing what they do best. Evaluating each nut by scent and sound, they nimbly shell the good ones and place the meat onto a conveyor belt while tossing the bad ones over their shoulders into a giant trash chute.

Like Wonka, Tim Burton also wanted the real thing – live, trained squirrels. “When I found out what was involved, it was a bit overwhelming,” says Senior Animal Trainer Mike Alexander, of Birds & Animals Unlimited. Alexander was happy to re-team with Burton following his successful stint as a chimpanzee wrangler on Planet of the Apes, but admits, “squirrels can be very tough, and training 100 of them was inconceivable.”

Ultimately, the animals on screen were an artful amalgamation of skillfully crafted animatronics plus some CG and multiple images along with 40 individual, rambunctious and very real squirrels to set the standard and lead the animal action.

Alexander’s team of four trainers (under the watchful eye of a Humane Society rep), spent 19 weeks with their lively charges, providing mostly one-on-one attention. Some of the animals came from private homes in the UK while the majority were recruited from local rescue shelters. Once rescued, squirrels cannot be released to the wild, by law, for their own protection, so those that were not returned to their owners when filming wrapped were adopted by Birds & Animals Unlimited, where they will be cared for until possibly called for another job.

While undeniably intelligent and, Alexander attests, “incredibly photogenic,” squirrels are notoriously difficult to handle. Independent and unpredictable, “they’re not necessarily good at doing specific, intricate things,” he says. “They don’t like to sit still. They’re hard to keep in one place. The first couple of weeks were spent in just getting the animals to come out of their crates and sit with us, nevermind any of the things they were supposed to do.

“We took baby steps,” he continues. “After they were comfortable sitting with us we introduced them to the props. We taught them to pick up a nut and put it into a metal bowl, which is not what they’d do in the movie but once they got the idea of picking the nut up and putting it into a bowl we could change the bowl to a conveyer belt. Once they grasped the basic concepts, they began to learn faster and things started coming together.”

Each squirrel had a name and it wasn’t long before individual personalities and talents emerged. “All of them are capable of learning, but some are naturally better at certain things than others,” says Alexander. “We found that some of them had no interest at all in picking up the nut, while others, once they had it, refused to let it go. Those that didn’t lend themselves to being `good nut squirrels’ were moved to a second group, being trained to run across the floor toward Veruca. Our smartest squirrels do the nut gag.”

There was a limit to what the real squirrels could do, by their nature or in deference to the potential danger of a scene. In those cases, animatronic or CG troops were called in.

“Tim wanted to use live squirrels as much as possible,” notes Nick Davis. “But some actions they are just not physically able to do, for example, throwing nuts over their shoulders. Physiologically, their bodies don’t work that way. Our job was to make the CGI squirrels as realistic as possible, to interact with humans in a kind of anthropomorphic way and yet remain absolutely true to their animal nature. Squirrels have a unique dynamic energy and that’s what attracted Tim. He didn’t want to shoot in high-speed or interfere in any way with that natural edge, that intensity and speed that’s utterly charming and can be a bit unnerving.”

Jon Thum, Visual Effects Supervisor for Framestore-CFC, came aboard to lend his expertise to the squirrel action, eventually contributing 88 VFX shots to the mix, “multiplying the real squirrels in about 15 shots as well as the much harder task of creating squirrels from scratch for another 64. Some shots of the squirrels on stools, turning their heads, had to be CG, and once they are on the floor they are mostly CG shots.”

Multiplication meant capturing the animals performing on cue, one at a time, and joining the images to present the group in unison. For example, where the squirrels are meant to jump from their stools en masse and run toward Veruca, Thum explains, “they could jump, but not all at the same time. So we had to shoot each squirrel alone, jumping off its stool, and then synchronize them into one shot.”

To create the virtual squirrels, Thum’s team “took loads of reference footage of the real thing. We had them running, jumping, shelling nuts, tugging at bits of fabric. Animation cycles were built based on this reference to use in all the shots, then for any `hero’ squirrels the animators would go in and keyframe that squirrel individually. In some shots our job was to animate actions the animals could not do, like tap Veruca on the head, but the movements you see them doing right before and after that are referenced from real squirrels.”

The computer images were then painstakingly rendered hair by hair to convey individuality, as Thum describes. “The tricky part was that many CG shots had to cut with shots of the real animals and we found that our close-up squirrels needed five million hairs to look authentic.” Fur was groomed to match the tiniest details of length, color and direction of growth. Nuances of movement such as breathing and twitching were added to complete the effect.

Additionally, Scanlan produced 12 animatronic models, plus some partials attached to hand-held poles. “In most of the shots there will be a live squirrel in the foreground performing an action and several animatronics in the background repeating it,” he says. The advantage of animatronics is that they don’t mind doing things endlessly and they don’t complain; but they’re never going to appear as real, so mixing and matching is the way to go.”

Scanlan’s puppet crew were driven by internal motor packs that enabled a wide range of motion including moving their heads, holding a nut and shaking it or listening to it, and flicking their tails around. “We could program and control them to do whatever Tim needed.”

When Veruca tries to kidnap a squirrel and is summarily knocked down by the incensed rodents en masse, a number of animatronic animals join their warm-blooded brethren in the fray, designed by Scanlan “with little hand and mouth springs to grasp onto the fabric of her dress.”

Great care was taken to avoid injuring squirrels that might dart underneath her or her stunt double as Veruca hits the ground. In fact, she lands on an unseen platform just above the ground, with ample clearance below. Supplementing the animal actors with animatronics and CGI in this scene created the striking effect of Veruca being completely covered in squirrels.

These production notes provided by Warner Bros. Pictures.

Charlie and The Chocolate Factory

Starring: Johnny Depp, Freddie Highmore, David Kelly, AnnaSophia Robb, Jordan Fry, Julia Winter, Philip Wiegratz

Directed by: Tim Burton

Screenplay by: John August

Release Date: July 15th, 2005

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for quirky situations, action and mild language.

Studio: Warner Bros. Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $206,459,076 (43.5%)

Foreign: $268,509,687 (56.5%)

Total: $474,968,763 (Worldwide)