Producer (and Regency Enterprises founder) Arnon Milchan’s passion for RUNAWAY JURY dates back to the publication of John Grisham’s best-selling novel in 1996. Having previously produced two successful Grisham adaptations – “A Time to Kill” and “The Client” – Milchan thought RUNAWAY JURY’s compelling story and surprising plot twists could be turned into an powerful movie.

When Gary Fleder, who helmed Regency’s hit thriller “Don’t Say a Word,” agreed to direct RUNAWAY JURY, Milchan was ready to move the project toward production. Fleder appreciated that RUNAWAY JURY couldn’t be pigeon-holed in a genre. “It’s not simply a courtroom drama and it’s not strictly a thriller,” explains the director. “For me, the hook is that it’s a heist movie in a courtroom; it’s about the theft of a jury.

“In our movie, there are several people trying to steal a jury. Not win a jury, but steal it. That’s the objective of Nick and Marlee, played by John Cusack and Rachel Weisz, as well as the powerful jury consultant Rankin Fitch, played by Gene Hackman. And ultimately, it might even be the objective of decent and compassionate attorney Wendall Rohr, played by Dustin Hoffman. A heist movie in a courthouse is something I’d never seen before.”

Fleder and Milchan were passionate about this aspect of the story. “For us,” says Fleder, “RUNAWAY JURY was less about a trial about the specific nature of the trial, and more about the idea of rigging and controlling over a jury. “In Grisham’s body of work this is a unique story. It isn’t David vs. Goliath; there isn’t the typical underdog. It’s a much more morally ambiguous piece.”

The character of Rankin Fitch was another key selling point for the filmmakers. “He’s someone who’s self-aware and smart and, therefore, daunting,” says Fleder. “Fitch is a great character because he has his own moral center which happens to be one not shared by most people.”

The script’s moral ambiguity was yet another draw. RUNAWAY JURY’s characters are not painted in black-and-white as clear-cut good guys and bad guys but rather in shades of gray. “RUNAWAY JURY challenges the audience because the film isn’t clear about who’s ‘good’ and who’s ‘evil’,” says Fleder. “Fitch is antagonist, but Nick and Marlee are involved with jury manipulation as well.’

For the role of juror Nick Easter, Fleder thought John Cusack would be ideal. “I had a very short list of actors for this manipulative, charming and funny character,” says Fleder. Fleder’s first choice was Cusack whose work he has always admired. “John has a great balance of charm and humor, but also has an edge and a dark side.”

RUNAWAY JURY’s twists and turns and the complexity of the Nick Easter character were the project’s principal attractions for Cusack. “The focus on jury tampering makes it a drama that hasn’t been done before,” says Cusack. “It’s really two different movies; it looks and has the flavor of a courtroom drama, but there are other things going on. For me, the movie is about greed, obstruction of justice and how the system has become corrupted. It’s also a movie about human nature and manipulation.”

Cusack’s interest in RUNAWAY JURY was piqued when Gene Hackman and Dustin Hoffman joined the cast. “I always wanted to work with Gene and Dustin,” notes Cusack. “They were two of my heroes when I was growing up. Watching their films led me to think that I’d like to try to do what they do. So working with them was exciting.”

Once ensconced on the jury, Cusack’s Nick Easter slowly emerges as a kind of jury quarterback or as Cusack explains, “He’s the straw that stirs the drinks. During the jury selection process Nick tries to ‘read’ the other jurors and figure out where their sympathies lay. He has to enlist fellow jurors to his cause without them knowing they’re being enlisted. He must be an astute judge of human nature. For a while you think he may be conning people, but then you find out something else entirely different may be going on.”

To play Nick’s formidable nemesis, jury consultant Rankin Fitch, Fleder couldn’t imagine anyone other than Gene Hackman. “Gene can play an antagonist and make audiences understand his point of view,” says Fleder. “Gene and I wanted audiences to see Fitch as someone who’s not bad just because that’s just the way he is, but rather as a guy who is motivated to behave as he does. Fitch doesn’t believe in the jury system. He doesn’t think that jurors should be afforded the right, the privilege and the power to decide precedent.”

Fleder and Hackman established a communications shorthand. “I told Gene that I saw Fitch moving like a Mako shark, that he was aerodynamic, streamlined and precise,” says Fleder. “He understood and that’s why in his very first scene, when he walks into his War Room with his assistant Amanda and learns that one of his employees is late because he missed a connecting flight, Fitch says, ‘Fine, replace him.’ That immediately sets up his character as a guy who doesn’t tolerate unprofessionalism or suffer fools.”

RUNAWAY JURY is Hackman’s third film based on a John Grisham novel, following “The Firm” and “The Chamber.” Why the attraction to Grisham’s work? Hackman puts it succinctly: “Because he writes highly dramatic kinds of scenes for actors and we like that.”

Hackman says Fitch is a businessman who employs unsavory methods to get what he wants. “Fitch arrives in New Orleans to put together a team of high tech personnel who delve extensively into the backgrounds of potential jurors and try to sway their opinions. In some cases this even involves blackmail or physical confrontations.

“I think ‘money’ is a key word for Fitch,” Hackman continues. “He’s a person who loves the competition, loves the game. And it just so happens that the game also makes him a lot of money. Although he doesn’t have principles, he does have needs and beating somebody at the game fulfills those needs.”

Hackman enjoyed his character’s perspective on seemingly simple things. “When he first enters the courthouse,” says the actor, “Fitch talks about how he loves the smell of the courtroom, the 200 year-old mahogany, furniture polish, cheap cologne and body odor. And he loves what comes with that, the tension, the humanity. Even though Fitch may not be a humane man, I think he’s fascinated by the human condition.”

At the opposite end of the moral spectrum is Wendall Rohr, the attorney representing a widow who holds a massive corporation responsible for her husband’s death. When Dustin Hoffman expressed interest in playing Rohr, the character was rewritten for the actor and the role was expanded from the novel.

Unlike Fitch, Rohr has a strong ethical center. “If law were religion, then Fitch would be an atheist, Nick and Marlee would be agnostics and Rohr would be a believer,” says Gary Fleder.

“Dustin brought a lot of that to the role,” Fleder continues. “I think if the story had had two predatory attorneys, there would be no one to cling to beyond Nick and Marlee who are themselves morally indefinite. By having Rohr fight the corruption around him, you have a stake in these people and certainly with Rohr. Once Dustin came aboard I thought it would be a shame not to enlarge and enhance the role.”

Hoffman and Fleder spent hours examining Rohr’s ethics and principles. Says Hoffman: “There’s a whole other side to Rohr. He has an ethos that has been diminishing in the profession for some time. We’re living in a time when the bar hasn’t just been lowered, but continually seems to drop.

“When the Bill of Rights was constructed, and its creators talked about people being judged by their peers,” continues Hoffman, “they had no clue that today we would have a sophisticated jury consulting apparatus that can program jurors in such a way that the verdict is in before the trial starts; the whole banana is in picking the jury.”

Hoffman considers Rohr to be unique for a lawyer of our time. “I think he’s rarified,” says Hoffman. “Like the character Gregory Peck played in ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ Rohr is a decent human being. It’s like remembering the days when doctors used to make house calls and when lawyers were not only ethical, but wanted to play by the rules.”

The contrasts between Rohr and his opponent fascinated Hoffman. “Fitch and Rohr are archetypes,” says Hoffman. “Fitch represents success, period. He must win, succeed and make a lot of money – that’s the bottom line. Rohr is a dinosaur, a relic who still believes in fighting the ‘good fight,’ but he’s told to get with the program, it’s the only way.”

Hoffman appreciated the opportunity to act in intense courtroom scenes. “What I enjoyed about playing a lawyer in those scenes,” says Hoffman, “was that Gary Fleder made certain the courtroom was filled with people. It really felt like an actual courtroom; it was a glorious feeling because, in a sense it was theatre in the round. I had an audience to play to and if you’re an actor you live and die for an audience.”

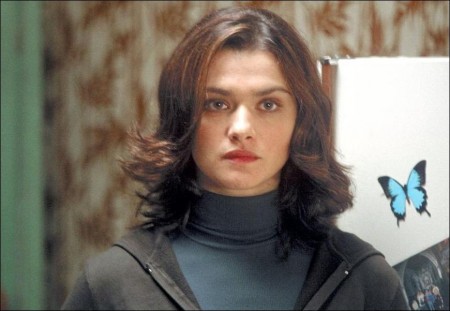

Rohr’s ethics are tested by Marlee, a young woman who may be partnered with Nick Easter. The two qualities that Fleder believed were essential for the character were likeability and mystery. After seeing Rachel Weisz’s performances in several films, most notably in “About a Boy,” Fleder felt she possessed both. “Rachel has a mysterious quality that I thought was necessary for Marlee in terms of what drives her and who she is,” says the director.

Notes Weisz: “I wanted to play a character that is playing a character. In fact, Marlee is playing several different ‘roles.’ Eventually we learn that Marlee isn’t necessarily who you think she is so it was interesting to construct a character that was pretending to be somebody else. It’s always exciting and challenging to try to find the mask behind the mask.”

Weisz relished the opportunity to play opposite all three of her leading men. “I loved working with John Cusack,” says Weisz. “John really has his own style, his own way of doing things. He’s relaxed and free and he improvises a lot. John always kept things fresh with a wonderful energy. And he can paint any color; he’s alternately funny, dark and light. So he was just a great partner to ‘dance’ with.”

Weisz has one major scene each with Hackman and Hoffman, as Marlee tries to sell the jury to each of their characters. With Hackman, the assignation takes place on a streetcar. “We played it like we were having a date,” explains Weisz. “Gene knows how to play villains in the most charming way imaginable so it’s almost impossible to dislike him even though Fitch is evil and corrupt. Gene’s so deeply charming that he just seduces you. And Marlee tries to seduce him back. At the same time she has to be tough with Fitch, but it’s hard to out-tough Gene Hackman.”

And what was it like working with the two acting icons? “It doesn’t really get much more exciting than working with Gene Hackman and Dustin Hoffman,” says Weisz. “They work very differently from each other, but they’re both deeply charming. They’re movie stars who are basically character actors, but they have the kind of sexuality of leading men.”

For the large supporting cast, including the members of the jury and both legal teams, Fleder chose actors familiar to audiences by face if not by name. As the director explains: “In a film like `Twelve Angry Men,’ you have the entire movie to develop, write for and create these characters. We didn’t have that opportunity. We had somewhere between 25 and 35 characters to play out in the film, so I had to deal with the jury in a sort of shorthand way.

“It was very important to have audiences know quickly who each person was, not by caricature, but by persona,” says Fleder. “Therefore, we cast actors that people would feel they know or would impart a sense of their characters very quickly.

“With people like Bruce Davison as defense counsel Durwood Cable, Bruce McGill as Judge Harkin and Jeremy Piven as Rohr’s jury consultant Lawrence Green, I knew it wouldn’t be about coaching them. It would be about giving them direction and shape and then letting them fill in the rest.”

Fleder told the actors playing jurors that he wanted them to overlap their dialogue and to improvise. “The actors brought improvisational layers to the picture,” says Fleder. “There wasn’t a scene with the jury where we didn’t add material. The jury scenes are like a film within a larger film, where we rehearsed and, as we shot more and more takes, more dialogue came out.”

Shooting scenes set in the jury room was one of Fleder’s greatest challenges. “I’ve done four other movies and about 15 hours of television and I’ve learned that you can never get completely comfortable with is filming scenes with 15 actors in a room,” says the director.

Fleder strove to give RUNAWAY JURY’s courtroom scenes a flavor and energy unseen in other films. “RUNAWAY JURY is about the pervasiveness of corruption in the law and, in shooting the picture, I wanted to represent that concept cinematically,” says Fleder. “When we first enter the courtroom I photographed it reverentially, as many courtroom films have. As the movie evolves we corrupt that environment, shooting a lot of the scenes with a handheld camera or with a Steadicam, often jumping the stage line to add a sense of geographical uncertainty.”

Cinematographer Robert Elswit’s lighting was another critical element in mapping out the film’s narrative. Each scene has its own quality of light, serving as a metaphor to, or establishing, the action, characters and mood.

Executive producer Jeffrey Downer, a frequent Fleder collaborator, is no stranger to large-scale movies, having worked on “Courage Under Fire” and “Speed 2: Cruise Control.” RUNAWAY JURY, with 75 speaking roles, including 25 principals in the courtroom scenes, and 3000 extras, presented a unique set of logistical challenges. “Other films of this magnitude have a lot of actors but not with so many working every day,” says Downer.

While John Grisham’s novel was set in Biloxi, Mississippi, the filmmakers opted to shoot RUNAWAY JURY in New Orleans, with the production using over 50 locations in the city, mostly in the French Quarter. “New Orleans is itself a character in the film,” explains Fleder. “There are two sides to the city: a beautiful, heroic-like architectural facade that is like the character of a hero, but also a dark side underneath. Together they reflect the players in the story. It was the perfect locale for the film.”

To facilitate the intricate and complex shots devised by Fleder, the filmmakers built several sets on a soundstage. Production designer Nelson Coates, another longtime Fleder associate, supervised the construction of a modular set that enabled Fleder to shoot from almost every conceivable angle.

In addition, Fleder and Coates had the jury box and witness box put on rollers, which facilitated greater shooting choices. “I wanted as much as possible to connect the elements in the film,” says Fleder. “That way I could have, in one shot, the jury in the foreground, an attorney in the mid-ground and the judge in the background. The ability to move the elements around physically was very important.”

Hackman and Hoffman

Academy Award-winning actors Gene Hackman and Dustin Hoffman have been the best of friends for 46 years, since they were students together at the Pasadena Playhouse in the late 1950s. Remarkably, RUNAWAY JURY represents their first motion picture collaboration.

When Hackman and his then-wife moved to New York, Hoffman followed several years later and initially stayed in their small apartment, sleeping in the kitchen next to the bathtub. Both were struggling New York actors, looking for work on stage and paying the bills with odd jobs. They both worked at Saks 34th Street, and at Howard Johnson’s, where both ended up being fired. Hackman also worked for the Padded Wagon Moving Company, moving furniture from tenements that had no elevators, often carrying refrigerators on his back, and Hoffman worked as a toy demonstrator at Macy’s.

At the time, neither actor could have envisioned being a leading man, much less a movie star. According to Hoffman, “at that time if the acting gods, or the devil, asked us to sign on the dotted line and you’d be in a resident theater in Ohio, not even off-Broadway, but you’d be a working actor for the rest of your life, we would have signed in a minute. What we wanted to do was work steadily as actors.”

“It never occurred to me that I would ever do film work,” adds Hackman, “because it was still the era of the studio system, when actors were under contract and studio chiefs wanted a specific leading man ‘look.’ I think that was a plus for me because I felt I would never be in films and so I had to really work harder on stage. And because Dustin and I stayed in New York as long as we did that held us in good stead.”

Times changed and after some highly praised theatre work, both Hackman and Hoffman were cast in their breakthrough roles, for Hackman “Bonnie and Clyde,” for Hoffman, “The Graduate.”

After the ensuing years of acclaimed performances in classic films that have made both actors icons, Hackman and Hoffman finally found themselves working together on RUNAWAY JURY. “We tried to collaborate a number of times before,” says Hoffman, “but each time, for some reason, it didn’t work out. It’s just one of those unexplainable things.”

To Hoffman what was really special about collaborating with Hackman after so many years of friendship was how little had changed between them over the years. “After all this time, the most moving aspect of working together was that we really didn’t feel in any way differently than when we first met. We still have a tenacity of trying to be authentic and at the same time we still have an insecurity that has remained constant all these years. And I’m not sure that insecurity is a bad thing to have.”

Hackman agrees: “It’s absolutely a good thing because it keeps you alive. In a strange way you’re never secure. You’re always on edge.”

“That was the revelatory thing,” adds Hoffman, “I don’t think we were doing anything differently than 46 years ago when we were in our first acting class together. We arrived on the set as frightened as when we arrived to do our first scene back then.”

Hackman and Hoffman are fans of each other’s work. “There are two sides to Gene Hackman,” says Hoffman. “He’s always had the ability to be extremely honest and natural in his work. He’s intelligent and has a wonderful sense of humor that he can incorporate into his character. The other side of Gene, which I think isn’t recognized enough, is that he may be one of the two or three great character actors we’ve had in the history of film. If you look at the arc of his work, that he can go from `Scarecrow’ to `Young Frankenstein’ to Popeye Doyle in `The French Connection’ to ‘The Conversation’ to Fitch in RUNAWAY JURY, you can see this disparate group of characters and his range. He’s an extraordinary actor, both a craftsman and an artist.”

Hackman has similar respect for Hoffman’s body of work. “With performances in films like ‘Tootsie,’ ‘Midnight Cowboy’ and ‘Rainman’ he showed what an amazing actor he is. He takes big chances, a big bite out of something, which I love in acting. You fail a lot of times, but a lot of times it’s brilliant work. And I think he has a better percentage in that kind of effort than almost anybody in the profession.”

Hackman says the dynamic between Fitch and Rohr is an exciting one. “Fitch is dealing in an illegal process. Even though he’s supposedly just a jury consultant he goes beyond what’s really legal. And Rohr is a very high-minded ethical lawyer. Where Rohr is a very principled man, Fitch is totally unprincipled. So when they finally confront each other toward the end of the film an audience can imagine what kind of conflict that’s going to be.”

Hoffman and Hackman see their respective characters as archetypes. “I represent this; he represents that,” says Hoffman. “Rohr is this anomaly. He refuses to sell his soul, to lower the bar in regard to his standards and ethics. Fitch is a very common character today. We see him in Hollywood, on Madison Ave. He’s the person who will do anything that he can get away with. But underneath all of that we somehow felt, even without saying it, that these guys really are very much the same, despite being such opposites and having a detestation for each other’s point of view.”

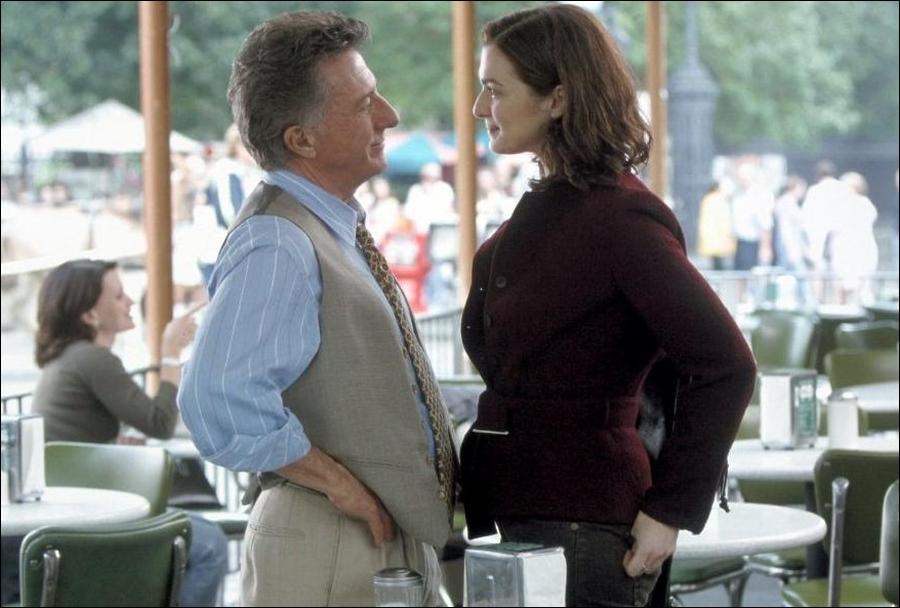

Although Hackman and Hoffman appear at the same time in several courtroom scenes, they exchange dialogue only once – during a chance meeting and subsequent confrontation. The scene is one of the film’s highlights.

“The Hackman/Hoffman confrontation scene is an example of where rehearsal paid off in a huge way,” says Fleder. “We had one 12-hour day to shoot this five-page scene, which really seemed more like two days worth of work. We rehearsed the scene for five hours the day prior to shooting it. We did a table read and talked about every beat. We refined, changed, cut some lines and talked about it. Then we blocked and staged it.”

For Fleder, directing that scene and the two acting legends was “the highlight of my career. Anything could have gone wrong, but nothing did. And that night I met Gene and Dustin for a drink after they went to a Hornets game and they were just ecstatic because they knew that they had nailed it.”

Runaway Jury

Directed by: Gary Fleder

Starring: John Cusack, Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, Rachel Weisz, Bruce McGill, Jeremy Piven, Jennifer Beals, Melora Walters

Screenplay: Brian Koppelman, David Levien

Production Design by: Nelson Coates

Cinematography by: Robert Elswit

Film Editing by: William Steinkamp

Costume Design by: Abigail Murray

Set Decoration by: Tessa Posnansky

Music by: Christopher Young

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for violence, language, thematic elements.

Studio: 20th Century Fox

Release Date: October 17, 2003