Using the narrative outline from The Far Side of the World also allowed the movie to be concentrated almost completely at sea, a unique and original approach that Peter Weir understood as the key to capturing the spirit and detail of O’Brian’s novels.

The film uses every state-of-the-art motion picture technique and an obsessive attention to accuracy and detail to put the audience back in time – not, as so common now, forward to some science fiction world – and lets us experience an adventure aboard a ship in Nelson’s Navy 200 years ago. From the splinter of wood in an attack to the heat of the doldrums, to rounding Cape Horn in a violent storm, MASTER AND COMMANDER puts the audience at sea as never before in film.

But for all that spectacle, it is the attention to characters and emotion that separate Patrick O’Brian and Peter Weir from other storytellers who have plied these waters.

Patrick O’Brian’s 20-volume Aubrey / Maturin opus, which reflected a lifetime of research, was Weir’s touchstone. The director never wavered from his commitment to capturing the detail and spirit of O’Brian’s world and characters, and brings an unprecedented level of historical realism to the film.

“Patrick O’Brian’s prose is magnificent,” says Weir. “He’s a writer of the first order. Of course, this was one of the most challenging aspects about adapting his work. When you adapt any book, the words fall out onto the table and you have to replace the prose with images. It has been a great challenge to tell this story visually in a way that does justice to O’Brian’s words.”

As Weir and Collee began writing the screenplay, they marked up O’Brian’s books under the headings: “Divisions,” “Crew,” “Jack and Stephen Dialogue,” and so on. These references were in turn photocopied and turned into books themselves – “handy cribs for cast and crew,” notes Weir.

“I surrounded myself with artifacts of the period as I worked on the script – swords, belt-buckles, maps, hoping to draw down the muse,” Weir continues. “Music was another aid, as I groped in the dark, trying to find my way back in time.”

According to co-screenwriter John Collee, MASTER AND COMMANDER, set largely aboard the ship Surprise, points to Weir’s consummate ability to create vivid, enclosed worlds. “That’s what Peter does brilliantly well, as in Witness and The Truman Show. He wanted MASTER AND COMMANDER to create a floating universe.”

At the core of Patrick O’Brian’s works are the characters of Lucky Jack Aubrey and Dr. Stephen Maturin, and their “study-in-contrasts” friendship. The friendship between Jack and Stephen is one of the most vivid and unexpected in modern literature. They are unique creations and very much the reason there are twenty Aubrey/Maturin novels. Jack is a fusion of the best traits of several real-life captains – a brilliant seaman and genius warrior, if a reluctant follower of orders. He also is exuberant, loud and a connoisseur of bad jokes. Stephen is a brilliant surgeon, naturalist and “lubber” whose courage matches Jack’s.

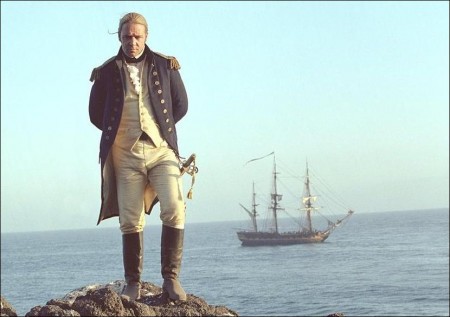

It took a star with an imposing presence, Russell Crowe, to play the bigger-than-life Jack Aubrey. Much of the magic of O’Brian’s work is pairing the captain with his natural opposite: a man of science whose courage matches Jack’s: Stephen Maturin, played by Paul Bettany.

Peter Weir’s celebrated body of work was a key draw for Russell Crowe. “I’m a longtime fan of Peter’s movies,” says the actor, “and I had always wanted to work with him. I’d grown up with Peter’s movies. For instance, I remember the most terrified I’d been in my young life was being in a cinema watching The Last Wave.”

Crowe was also fascinated with the character of Lucky Jack. “He was a kind of man who doesn’t exist anymore; there’s no template for Jack Aubrey,” says Crowe. “If you are talking about the British Royal Navy as his employer, he is a very unruly employee. However, in the broader sense of the mission with which he is charged as captain, he might not do it the way you want him to do it, but his results at the end of the day will be far more than you intended.”

Weir says Crowe was born to play Lucky Jack. “Russell has a natural energy and authority, and he took command of that ship from the beginning.”

Crowe appreciated some of the perks of “command.” “Every day between my trailer and the set, I would hear ‘Good morning, Captain’ about seventy or eighty times,” says the actor. “Actually, it was difficult giving up the uniform; I’d grown quite fond of it.”

Crowe was pleased to rejoin Paul Bettany who played, memorably, Crowe’s imaginary roommate in A Beautiful Mind. Their collaboration in film proved invaluable in helping the actors create their characters’ relationship in MASTER AND COMMANDER. Says Crowe: “We developed a kind of creative shorthand in A Beautiful Mind that I thought would serve us well in establishing quickly and effectively the Jack-Stephen dynamic. I was so glad that Peter made the decision to cast Paul. There are rhythms and things that we just understand of each other. With another person, you might actually have had to break down a scene and explain it. Paul and I were able to get to a point of depth that you might have to work ten times harder with somebody else to even touch on.”

“It was a joy to watch Paul take the character and make it his own, yet at the same time have it deeply rooted in Patrick O’Brian’s writing,” says Weir. “Russell and Paul are beautifully weighted opposite each other, and you believe they’re friends. It’s as if Maturin, as Paul plays him, is the shape of the modern man and Russell as Jack is from a bygone time.”

Bettany says two elements attracted him to MASTER AND COMMANDER: action and characters. “Any fan of Patrick O’Brian’s books knows them to be real page turners,” says Bettany, “and I see the film as an action movie within which is a richly detailed friendship that endures some life-altering situations. I found that really intriguing.”

A critical point in the friendship between Bettany’s Stephen Maturin and Crowe’s Lucky Jack comes after a surprise attack by the Acheron that leaves Captain Aubrey’s ship severely damaged and a number of his men dead or critically wounded. Despite (or perhaps spurred on by) the odds against him, Jack is more determined than ever to complete his mission to best the Acheron. His single-minded focus on the enemy ship becomes a concern for Stephen.

“Stephen studies people the way he studies animals; he certainly studies Jack,” says Bettany. “I think what Stephen finds intriguing about Jack is that he is the exception to the rule that ‘power corrupts’ – Jack wields his power wisely. But that is really tested in this film. Stephen begins to think that Jack’s goal of catching the Acheron is turning into an obsession, which could be a detriment to his crew.”

To fill the supporting roles, Weir worked closely with U.K. casting director Mary Selway. They searched for top acting talent who had the necessary endurance for the demanding six-month shoot and a physical appearance that suggested another time and place. The formidable lineup of actors includes Billy Boyd (of Lord of the Rings fame), James D’Arcy, Bryan Dick, Lee Ingleby, George Innes, Mark Lewis Jones, Chris Larkin, Richard McCabe, Ian Mercer, Robert Pugh and David Threlfall.

most importantly, the paintings of naval actions at sea. “Studying the paintings made me determined to find faces that looked of the period,” says Weir. This led him to cast in Poland, “to get us as far away as possible from people raised on a Western diet, with Kodak-ready smiles or expressions of world-weary cynicism.”

The casting of the crew, some 130 men, received as much attention as did that of the principals. Searching for “18th century faces” was left to Judy Bouley, and, incredibly, she saw more than 7,000 hopefuls. “As a guide, we had reproductions of paintings and sketches of the period and most importantly, a rare set of photographs, taken in the mid-1840s of English fishermen, shot by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson,” says Weir.

“We went to the ends of the earth to find these people,” says producer Duncan Henderson. “We have background from Poland, Senegal, Australia and Sudan – people who came from all over the world to work with us on this film.”

Some background artists were seasoned tall ship sailors. Their gravity-defying feats of scrambling up and down the ships’ rigging lent yet another touch of authenticity to the film. Another key “casting” challenge was finding the ideal vessel to portray the HMS Surprise, Captain Aubrey’s 28-gun warship. Early in pre-production, during a trip to Europe, Weir walked the deck of the restored HMS Victory, the vessel commanded by Lord Nelson in the Battle of Trafalgar. In addition, the director attended several tall ship festivals and spoke with scores of people from the worldwide tall ship community.

In 2000 Weir joined Captain Chris Blake (who would become one of the film’s many prominent technical advisors) for a cruise on the Endeavor, a museum-quality replica of Captain Cook’s famous vessel. A year later, Weir embarked on a second voyage aboard the Endeavor, this time bringing along producer Duncan Henderson, executive producer Alan Curtiss and cinematographer Russell Boyd. “I wanted to be sure they too would have the experience stored in their bones when it came time for our ‘voyage’,” says the director.

Weir’s search ultimately led him to the American tall ship Rose, home port Rhode Island. The three-masted wooden frigate, formerly the country’s largest sailing school vessel, is a twentieth century replica of a 1800s-era British Royal Navy ship.

Twentieth Century Fox purchased the Rose. (Upon completion of principal photography, Fox donated the ship back to a non-profit naval history organization.) The Rose traveled through the Panama Canal en route from Rhode Island to the West Coast, enduring a hurricane and a broken mast before arriving at a San Diego dry dock to prepare for her transformation into HMS Surprise.

In its incarnation as HMS Surprise, the Rose was utilized for several weeks of shooting at sea by first and second units. This unique “shooting stage” was retrofitted to be authentic to the period, as well as to be able to accommodate the principal cast, filmmakers, camera crew, hair, makeup, wardrobe, props and other departments necessary to shoot the scenes. The Rose’s actual crew manned the vessel as it moved through the Baja waters. (Russell Crowe also learned to sail The Rose, and assumed the “helm” on several occasions.)

“We’ve gone to great lengths for historical authenticity,” says master shipwright Leon Poindexter, another of the film’s technical and historical consultants. Poindexter also worked with twenty shipwrights to retrofit the Rose in San Diego, and helped relocate it to its production home in Ensenada, Mexico. “We received fully documented construction details from the Admiralty in the U.K., and used mathematical formulas to determine the proper anchor size,” says Poindexter. “Every inch of this ship, down to the placement of the mooring cables has been carefully researched.”

“I loved being out on the Rose,” says Russell Crowe, who earlier had sailed through tempest-tossed waters in Fiji (coincidentally in a boat named the Surprise) to begin preparing for his role as Jack Aubrey. “Climbing a mast on The Rose at sea, 137 feet above the ocean, was a highlight for me. Those days were really special; there was an immense sense of freedom because we weren’t connected to the land.”

The filmmakers built a second “HMS Surprise” – the 60-ton tank ship – over a four month period. This ship was placed in a 6 ½ – acre water tank at the Fox Studios Baja – home to Titanic. This Surprise was constructed completely from scratch, with painstaking attention to detail, down to the lanterns, hammocks and the aging of the ship and its sails.

At the same time, New Zealand-based special effects house Weta Workshop, part of the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy effects team, built detailed ship miniatures. Their Surprise was over 25 feet in length. Additional models were digitally constructed in the computer of visual effects house Asylum.

The massive tank ship in Mexico was mounted on a specially constructed gimbal, the largest ever used in a motion picture production. Powerful hydraulics brought to life the monstrous mechanism, which facilitated a complete range of motion, duplicating a ship’s movements at sea. “We rocked and rolled from Brazil to the Galapagos Islands in that tank,” says Weir.

Director of photography Russell Boyd notes that thanks to the gimbal, shooting on the tank sometimes felt like filming at sea. “The gimbal gave a pitching and rolling motion to the set, so that the whole set actually moved like a ship at sea,” says Boyd. “We all had to develop sea legs fairly early on, just to work on the tank ship.” Boyd and his team used a techno-crane with a libra head, with the camera sitting on three axes—horizontal, forward/backward and leveling – enabling them to counteract the ship’s movement.

A set representing the Surprise’s gun deck was also outfitted with a gimbal, and built on a bluff overlooking the ocean at Fox Studios Baja. This set, like the tank ship, could be rotated. A third gimbal was used for the Stage 3 Berth Deck, the low-ceilinged and cramped quarters where sailors slept in rows of hammocks and ate their meals. The Orlop Deck, the lowest deck of the Surprise, was situated on Stage 4, which later housed the Acheron gun deck, the site of major hand-to-hand fighting during the final battle.

Fox Baja soundstages housed other sets representing different deck levels of the Surprise, including the ship’s Great Cabin, on Stage 2. The Great Cabin housed Captain Aubrey’s relatively elaborate private quarters and served as the backdrop for dinner parties for the Captain and his officers, as well as scenes where Aubrey sought solitude to contemplate some difficult decisions. The Great Cabin was also a meeting place for Aubrey and Maturin, who would relax by playing duets on violin and cello.

Over a period of several months, the filmmakers constructed an Acheron tank ship, in a parking lot near the Studio’s front entrance. Upon this “Acheron’s” completion, it was divided into four portions and moved by a giant crane down the street and into the tank for use in the final battle. As the sets were readied, the actors portraying the officers and crew of the Surprise underwent training to immerse themselves in the rigors of life aboard ship. They trained in open ocean sailing on the Rose, climbing the rigging, navigation, small arms handling, cannons, sword fighting, military etiquette and learning work of the characters they portray in the film.

Creating The Most Realistic Storm

Peter Weir’s mandate for the film’s state-of-the-art visual effects work, comprising some 750 shots, was that they be “invisible” – no matter the amount of research and development, artistry and man-hours that went into creating the effects. “Peter insisted that MASTER AND COMMANDER not look like an effects film,” says visual effects supervisor Stefen Fangmeier of ILM. “If you don’t recognize the effects – if audiences just are in the moment and enjoy the spectacle and Peter’s personal vision – then we’ve done our job.”

Fangmeier and ILM embraced the notion of creating visual effects for a period film. “It’s a breath of fresh air to work on a personal piece grounded in reality,” he says. “Audiences are so used to laser blasts, space battles and the like. With MASTER AND COMMANDER we had the opportunity to enhance a world many of us have forgotten about. It’s a lot richer in many ways than any outer space galactic battle.”

MASTER AND COMMANDER’s “invisible” effects contribute to the creation of an epic typhoon sequence, the likes of which have never been experienced on film. In the story, Jack Aubrey pursues the Acheron, the Surprise rounds the Cape, the weather worsens, the seas and winds grow merciless – and the biggest challenge Jack has ever faced lies ahead: the full fury of a massive storm – on a 120-foot square-rigger.

State of the art visual effects merged with massive physical effects and, for the first time ever, real life footage of an actual storm captured on film at Cape Horn to create a typhoon as real as it is big.

“For the storm sequence we had to prep all the camera equipment for the storm sequence for getting absolutely soaked,” says director of photography Russell Boyd. “We used Hydroflex water bags and we completely encased the camera, but which still allowed it to be operational. We were able to shoot even with the millions of gallons of water that the special effects guys dumped on us.”

After cast and crew were positioned on the ship, the filmmakers brought the storm to life. First, they activated the gimbal, which put the ship in motion. Then wave and wind machines were switched on and water was pumped in front of two enormous jet engines, which broke down the water into a fog/mist effect. Four fans set up behind rainheads produced heavier rain, and, finally, massive dump tanks unleashed 8,000 gallons of water that cascaded across the deck of the ship, completely soaking cast and crew. The jet engines, wave and wind machines, fans and dump tanks combined to produce a deafening cacophony for on-set cast and crew.

While these physical effects played a key role in creating these epic scenes, important contributions were also made by footage of a real storm captured months earlier by Paul Atkins, aboard the Endeavor as it rounded Cape Horn. This is the first time actual storm footage has been integrated into such a sequence – it makes it look bigger, more realistic, and lends a critical “you-are-there” feel to the epic scene.

Integrating the Endeavor footage with the CG and physical effects was the biggest challenge facing Asylum. “We were blessed to have such a great element – the Endeavor storm footage – to begin with,” says visual effects supervisor Nathan McGuinness of Asylum. “Peter’s directive to us was to make it all very organic; to have all these elements, including physical and CG models of the Surprise, interact in a believable fashion.”

ILM created visual effects for another huge sequence – the final battle between the Surprise and the Acheron. Digital and miniature ships facilitated dynamic camera moves not possible while shooting at sea.

The visual effects teams worked closely with the film’s special effects and art departments to ensure that the computer generated ships matched the miniature models built by The Weta Workshop. Both CG and miniature models had to match the specifications of the Surprise tank ship, via constant reference to the hundreds of blueprints used for the tank ship’s construction

Much of the effects work was subtle, such as eliminating the Mexican coastline from scenes shot on the tank boat. Digital artists removed these and other images frame by frame. One of the “construction” tasks that fell to the visual effects department was the completion of the masts. Due to the weight of the tank ship on the gimbal, the filmmakers had to construct a shortened version of the main and fore masts. The visual effects teams extended those masts, rigging and sails.

Historical and Character Research

Peter Weir wanted MASTER AND COMMANDER to give the audience as accurate a feeling as possible of life aboard a fighting ship of the period. He and his team of historical consultants were relentless in their pursuit of period authenticity.

Young boys, some only eight years old, were often servants or “powder monkeys,” running back and forth to the gun deck delivering powder to the gun crews. In the case of officers, there was a training regimen wherein young gentlemen, many of noble birth, could be taken under the captain’s supervision aboard ship as midshipmen, studying and learning the books much as they would in a private school.

There were midshipmen as young as twelve, such as the Lord Blakeney character, played by newcomer Max Pirkis. Weir built up the parts of these younger actors so audiences would see how they were treated on board as equals. “They had to take the injuries, sail the ship, go into battle and fight alongside the men,” says Weir.

In 1805, with Britain’s King George III in his 45th year on the throne, the celebrated career of the heroic Lord Nelson was soon to come to an end with his death at The Battle of Trafalgar. War between Britain and France had been a constant throughout Nelson’s lifetime and continued through to 1815.

Russell Crowe shared Peter Weir’s passion for historical and character authenticity. “The reality of the situation for a man like Jack is that it is a very lonely job,” says Crowe. “Every ship’s captain I spoke with before we began this film discussed that loneliness aspect, and to be prepared for that. One shared with me a saying – ‘Not always right, but always certain’ – meaning that as captain, you can’t transmit any doubts you may have in the middle of a life-threatening situation.”

Crowe studied the nautical history, lore and skills required as a British Royal Navy captain of the time. He also learned the ins and outs of the ship, and became quite adept at climbing the rigging to the tops. Sailing master captain Andrew Reay-Ellers was one of the consultants who assisted Crowe in his research.

“We helped Russell recreate Jack Aubrey’s 20-year naval career,” says Reay-Ellers, “working for hours each week, from the nuts and bolts of every line onboard the ship, to sailing maneuvers, strategy, and that nature of a captain’s command. Russell felt that Jack, although as captain would never set a sail personally, was once a midshipman and would have that knowledge. Russell wanted to know everything I was teaching his men, and we went through a condensed version of a lifetime of learning the ship.”

Reay-Ellers was impressed with Crowe’s dedication to research and training. “He spent hours pouring over diagrams, reading some very dense literature on ship handling strategies, and he rose to the challenge. At the same time, he was learning to play the violin and a type of sword fighting unique to that period and rank. It’s just mind-boggling, the amount of things he was simultaneously learning; he wanted that level of confidence, that air of casual knowledge that he knows every line on the ship, just the way Jack Aubrey would.”

Crowe’s violin training stems from Lucky Jack’s penchant for the instrument and his occasional musical pairings with Stephen Maturin, himself a cellist. Over a period of several months Crowe worked with longtime friend and Australian violin virtuoso Richard Tognetti (who later would help compose the film’s score), and with violinist Robert E. Greene, who previously worked with Crowe during A Beautiful Mind.

Preparing to portray Stephen Maturin led Paul Bettany along his own eclectic course of study. “I went with Peter Weir to the Royal College of Surgeons in London to meet with a surgeon there, Mick Crumplin, who was also an historian,” recalls Bettany. “Mick was helpful in terms of learning some of the medical procedures of the time, so that I had a grasp of how to perform them in the film.”

Bettany also dabbled in dissection during time spent at the Scripps Institute of Oceanographic Study in La Jolla, for background in pre-Darwin knowledge about insects, animals and fish.

To aid in their efforts to bring this era to life, the filmmakers utilized, in addition to their team of consultants, a wealth of historic resources at their disposal, including the cooperation of several museums, access to historical artifacts, paintings, diaries, illustrations, ships logs, original blueprints – as well as the richly detailed world described by Patrick O’Brian. An extensive resource library was housed on the studio lot, and cast and crew were encouraged to take advantage of this resource.

Costumes, Hair and Makeup

Costume designer Wendy Stites and her department created over two thousand uniforms for the Surprise officers, enlisted men, sailors and Marines, as well as for the French officers and crew of the Acheron.

Stites incorporated detailed costume notes culled from Patrick O’Brian’s novels into the designs. From O’Brian’s work and research, she learned that the sailors’ outfits of the period had been made of hemp, a fabric that has only made resurgence in the last fifteen years. Britain’s National Maritime Museum was an invaluable resource in research for the uniforms of the period. There, in a climate-controlled room, the filmmakers viewed original captains’ clothing, and felt their weight and texture.

Notes and measurements were taken of the details of the epaulets, buttons, fabric and gold braid used in the uniforms, so they could create replicas for the film. The costume department used fabrics from Pakistan, India, Scotland, Ireland, England and China, and had the officers and midshipmen’s costumes made in England. They waited until the last minute to fit the young actors portraying midshipmen, as they were growing every day. By the end of the film many of them had almost grown out of their costumes.

The venerable British textile firm Abimelech Hainsworth, manufacturers of woolen cloth since 1783, provided fabric for the officers’ jackets, and the renowned London firm M.B.A. Costumes tailored the officers’ uniforms. Kirsti Buckland, a Welsh woman whose family has been knitting seamen’s caps since the 1700s, created over 150 “Monmouth” knit hats for the film’s sailors from original patterns.

Distressing and maintaining the costumes was a major challenge. “We put the costumes on some of the actors and aged them specifically, according to their line of work on the ship and their personality,” says Stites. “We took into account their job aboard ship, how it would affect their clothes, and where it would be worn or torn.” Teams of textile experts worked in shifts seven days a week, continually maintaining the aging and weathered look required by the story.

Jack Aubrey’s body is a veritable roadmap of scar tissue, and in preparation for a specific scene, Russell Crowe and his makeup artist rigorously researched wounds the captain would have acquired on his adventures leading up to The Far Side of the World.

Key makeup artist Edouard Henriques and his crew researched and designed looks for 26 principal cast members and over 100 background artists. They looked at paintings, and read the O’Brian novels for character descriptions.

Henriques altered the makeup techniques to reflect the characters’ exposure to the elements, according to story’s various weather extremes. “We designed the makeups with translucent washes, waterproof makeup which we used to add roughness to the faces, and red sunburn lines on their bodies,” he says. “We made their noses red as well as the bottoms of their ears. As the journey continued, the characters moved to more brown tones, due to their months at sea.”

In addition, the makeup artists added staining and wear to the actors’ teeth. For the principals, individual molds of their teeth were made using very thin plastic membrane; they were then painted so the actors could pop them on rather than have their teeth individually painted each day. Makeup artists took care of up to 120 people a day for six months, dirtying their teeth, adding makeup “dirt” to their fingernails and faces, and enhancing some of their scars. For the final battle, those numbers grew to about four hundred people when the background portraying French sailors joined the production.

Key hair department’s Yolanda Toussieng studied portraits, paintings and photos of wigs, combs and razors which had been recovered from sunken ships of the time. Again, Patrick O’Brian’s novels provided a key source of information. “From the novels, we learned how they groomed themselves aboard the ship,” says Toussieng. “Men sometimes braided each other’s hair, using tar to keep their braids tight; they shaved once or twice a week, and washed their hair once a week, or so. Fresh water wasn’t plentiful aboard, so this, in part, dictated their grooming habits.”

Toussieng estimates she used around four hundred bundles of hair during the course of the shoot, using five bundles per person, by applying glue, heating it and adhering it to the actors’ own hair.

The Galapagos Islands

MASTER AND COMMADER has the distinction of being the only feature film ever to shoot on The Galapagos. A province of Ecuador, The Galapagos is home to a variety of unique plant and animal species, including the almost-extinct giant tortoise. When English naturalist Charles Darwin visited the Galapagos in 1835 on his historic voyage aboard HMS Beagle, he discovered a natural laboratory rich in flora and fauna. His research of the animal life there contributed to his theory of evolution and natural selection.

Before receiving permission to shoot on the Galapagos, the filmmakers spent months addressing the concerns of the Ecuadorian government and the Galapagos National Park representatives, regarding the scope of the film company’s activity in the Park, as well as the presentation of the Galapagos within the story.

The Galapagos scenes are the only time where the men of the Surprise leave their wooden world to touch land. The story’s reverence for the Islands is reflected in Stephen Maturin’s studies as a naturalist and in his intense desire to see the Islands during their journey.

“I love that aspect of Maturin; he gives us a glimpse of the world at that time, bursting with new developments in science and natural history,” says Weir. “It was an incredible era: there was a feeling that knowledge was opening up in ways that were completely new. Stephen’s activities hint, as Patrick O’Brian certainly intended, that Darwin was to come, less than forty years later, and make discoveries which he would later incorporate into his theory of evolution.”

Weir and a reduced shooting unit shot at the Galapagos for seven days. Cast members Paul Bettany, Max Pirkis and John DeSantis, along with 36 film crew members and all of the company’s equipment, were housed on the small tour ship the M/V Santa Cruz, a vessel built especially for moving around the Galapagos. Filmmakers, cast, crew and equipment were transported from the Santa Cruz to the islands each day via small boats, and all equipment was hand carried and removed from the islands each night.

While the filmmakers captured one-of-a-kind material during their visit to The Galapagos, logistical requirements dictated that they also recreate the area in Baja. Digital matte painter Robert Stromberg of Digital Backlot worked with ILM to transform the gray cliffs of Baja into the startling landscape of The Galapagos. (Stromberg and company even accentuated the color of the sky in the Galapagos footage, enhancing the Islands’ already impressive beauty.) In addition, Asylum digitally cloned birds, iguanas and other fauna native to The Galapagos, for these scenes shot in Baja.

According to Robert Stromberg, it’s hard to overestimate the importance of the Galapagos scenes. “It’s the only point in the movie you actually see land,” he points out, “making it a centerpiece of the movie. Peter wanted to make The Galapagos look almost like another planet to the men aboard the Surprise.”

Music

A trio of noted Australian musicians – Iva Davies, Richard Tognetti and Christopher Gordon – composed the film’s score. They previously collaborated on “The Ghost of Time,” a piece commissioned for the Millennium celebrations in Sydney, which came to the attention of Peter Weir. The director was so impressed, he played the piece on the MASTER AND COMMANDER set throughout production, and he asked its creators to write the music for his movie.

The score interweaves “Old World” and “New World” music, reflecting the talents and backgrounds of its composers. Iva Davies hails from both pop and classical traditions; Richard Tognetti, one of the world’s great violin virtuosos, taught Russell Crowe the ins and outs of the instrument; and film/television composer Christopher Gordon brought orchestral texture to the project.

Given the period, it comes as no surprise that the score is infused with source music from Bach (“Cello Suite”) and Mozart, among other great classical composers. Percussion dominates portions of the score. “Drums signal the forward movement of the ship,” says Davies, “that it’s on a mission. It brings you back into the action.” The score’s biggest surprise comes with its use of synthesizers. “Peter doesn’t make films in the expected way,” says Davies, “and for that reason we wanted the score to be not what everyone expected. Peter wanted some scenes to have what I call a kind of ‘futuristic’ sense” – conveying the idea that these 19th century sailors were cutting-edge explorers.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

Directed by: Peter Weir

Starring: Russell Crowe, Paul Bettany, Billy Boyd, James D’Arcy, Lee Ingleby, George Innes, Mark Lewis Jones, Chris Larkin

Screenplay: Peter Weir, John Collee, Patrick O’Brian

Production Design by: William Sandell

Cinematography by: Russell Boyd

Film Editing by: Lee Smith

Costume Design by: Wendy Stites

Set Decoration by: Robert Gould

Music by: Iva Davies, Christopher Gordon, Richard Tognetti

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for intense battle sequences, related images, brief language.

Studio: 20th Century Fox

elease Date: November 14, 2003