The paths of these two warriors converge when the young Emperor of Japan, wooed by American interests who covet the growing Japanese market, hires Algren to train Japan’s first modern, conscript army. But as the Emperor’s advisors attempt to eradicate the Samurai in preparation for a more Westernized and trade-friendly government, Algren finds himself unexpectedly impressed and influenced by his encounters with the Samurai. Their powerful convictions remind him of the man he once was.

Thrust now into harsh and unfamiliar territory, with his life and perhaps more important, his soul, in the balance, the troubled American soldier finds himself at the center of a violent and epic struggle between two eras and two worlds, with only his sense of honor to guide him.

Director Zwick Realizes Lifelong Dream

Although principal photography on The Last Samurai officially began in October of 2002, director Edward Zwick has long been fascinated by Japanese culture and Japanese films. In a sense, he has been imagining The Last Samurai since he was a teenager.

“I first saw Akira Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai when I was 17 and since then I’ve seen it more times than I can remember,” he admits. “In that single film there is everything a director needs to learn about storytelling, about the development of character, about shooting action, about dramatizing a theme. After seeing it, I set out to study every one of his films. Although I couldn’t know it at the time, it set me on the course of becoming a filmmaker.”

Long a student of history, Zwick found the period known as the Meiji Restoration particularly compelling. The end of the rule by the old Shogunate led to Japan’s first significant encounter with the West after a self-imposed isolation of 200 years.

“Most of all,” he says, “it was a time of transition. In every culture, that moment of change from the antique to the modern is especially poignant and dramatic. It is also wondrously visual. Each image, each landscape, each room tells the story, the juxtaposition of the old and new. A man in a bowler hat strolls beside a woman wearing a kimono. A man firing a repeating rifle faces a man wielding a sword.”

Zwick, whose Shakespeare in Love earned a Best Picture Oscar, is no stranger to stories from this period. His films Glory and Legends of the Fall were set at the end of the 19th century. “I am drawn back, again and again, to this historical moment,” he says. “There’s something moving, even hypnotic about observing a character going through a personal transformation at a time when the whole culture around him is likewise in turmoil.”

Multiple Oscar-nominee Tom Cruise, cast as the haunted Captain Algren, shares Zwick’s interest in and admiration for the Japanese ethos, specifically that of the Samurai. Like Zwick, he discovered Kurosawa and the Japanese oeuvre as a teenager, and acknowledges always having had “a deep respect and strong feeling for the Japanese culture and people, the elegance and beauty of the Samurai, their spirit of Bushido that teaches strength, compassion, fierce loyalty, their commitment to honoring their word and a willingness to give their lives for what they know is right. It’s essentially about taking responsibility for what you do and say, whatever the repercussions. More than a code for Samurai warriors, it’s a strong way to live a life – any life. It was something I could not resist. When Ed first sat down with me to discuss it, I just knew I had to make this picture. I have a very strong connection to its theme, as well as to the characters.”

Also a producer on The Last Samurai, Cruise says that the epic nature of the story, in addition to Algren’s emotional and philosophical arc and the opportunity to work with Edward Zwick and Marshall Herskovitz, were all enticing incentives. “This film is a full course meal,” he says. “The adventure and journey of the character, the world he enters and the people he meets – it’s a rich, challenging and truly fascinating story. From a production point of view, it has the broadest scope of anything I’ve done in my career: it’s physical, it’s dramatic, it’s romantic and it’s philosophical.”

“Frankly,” he continues, “what also attracted me was that we all three shared such enthusiasm for the subject. When I first started talking with Ed, he was so passionate and excited about it; he was like a 15-year-old boy, jumping around the room, painting the scenes with his hands. And he brought that passion with him throughout production.”

Zwick’s films have often explored the complexities of war and honor. To dramatize the differences as well as the common ground between a Western soldier and a Samurai warrior were irresistible. “First in college and then for years after, I read a great deal of Japanese history,” Zwick relates. “I was deeply moved by Ivan Morris’s The Nobility of Failure, which tells the story of Saigo Takamori, one of Japan’s most famous figures, who first helped create and then rebelled against the new government. His beautiful and tragic life became the point of departure for our fictional tale.”

The change from feudal Japan to a more modern society meant the demise of certain “archaic” customs and values epitomized by the Samurai. For many years, they held a highly respected place in the social order. Like England’s knights, Samurai soldiers protected the lords, or, in this case, the Shogunate, to which they had sworn fealty. As the knights upheld their system of chivalry, the Samurai lived by a code called Bushido, “the way of the warrior,” which emphasized, among other things, loyalty, courage, fortitude and sacrifice.

In contrast to the modern weapons the West now offered Japan, the Samurai seemed anachronistic to the proponents of progress. This new lust for all things modern left no room for the Samurai with their fabled swords and old-fashioned notions of honor, exemplified here by their last remaining leader, Katsumoto (played by Ken Watanabe) and his few devoted warriors. Katsumoto’s challenge is to maintain his personal principles in a society that no longer values them. His struggle, especially in combination with Algren’s own reluctant spiritual journey, appealed to Zwick.

“I’ve always found the core values of the Samurai culture to be both admirable and relevant,” he explains, “in particular, the understanding that violence and compassion exist side by side and that poetry, beauty and art are as much a part of a warrior’s training as swordsmanship or physical strength. Also, I’m interested in the unexpected possibility of spiritual rebirth reaching those lives for whom it seemed the least possible.” Addressing his desire to combine these elements in The Last Samurai, he says, “Our story is a romantic adventure in the broadest sense of the word and, at the same time, a very personal odyssey. The challenge is to create a story in which the relationships rival the larger context, the inner landscape resonating against the epic canvas.

“The character of Katsumoto is as intriguing to me as is the character of Algren,” Zwick continues. “Personally, I identify with his dilemma and see how it applies to many other aspects of modern life.”

As vividly as the Samurai code is expressed by Katsumoto and his brethren, it is also evident in Katsumoto’s sister, the young war widow Taka, who finds herself pressed into close quarters with Algren through the most bitter of circumstances. Taka, played by Japanese actress Koyuki, conducts herself with such strict composure that the American stranger does not suspect the complex and powerful emotions she feels towards him until he realizes that she is just as much a Samurai as her male counterparts.

Producer Paula Wagner, who, with Cruise, oversees Cruise/Wagner Productions, notes that Cruise’s enthusiasm for the film and his intense connection to and collaboration with Zwick and Herskovitz has much to do with Zwick’s unique, fervent vision of the project and the character Captain Nathan Algren. “Ed was able to combine the story’s epic sweep and action with the intimate, heroic journey of this powerful character,” she says. She adds that the film’s complexity appealed to Cruise/Wagner Productions, which has developed and produced an eclectic array of motion pictures, noting that, “This film works on many levels. The Last Samurai offers rich and layered characters, great action and adventure and, specifically in Captain Algren, a person who travels a great distance, literally and figuratively, to find himself and his values.”

The film had its genesis with a project at Radar Pictures in the early 90s about an American traveling to Japan in a similar time period. “We were struck by the parallels between the taming of the American West and the westernization of traditional Japan,” explains Radar Pictures’ Scott Kroopf, “and knew that there was a story to be told about how modernization diminished the two vastly different cultures.”

“We brought in Ed Zwick,” says Tom Engleman, also with Radar Pictures at the time, “whom I had known for years as a friend and neighbor. He was clearly the perfect guy to do it, because of his body of work and his interest in looking at the heroes of the American West from an entirely new perspective.”

Subsequently, Kroopf continues, “Ed suggested bringing in John Logan and it turned out that John, like Ed, was a student of the fall of the Samurai. In the end, our patience with the project was rewarded not only by the great screenplay but also by Ed’s incredible skill at mounting the movie.”

Zwick and Logan, Oscar-nominated screenwriter of Gladiator, agreed that the 1876-1877 Samurai revolt would be an exciting and provocative historic reference point for the film. “Developing the protagonist with Ed,” Logan remembers, “was one of the most challenging elements of the story. As we worked, the character of Captain Algren emerged as a truly tormented figure; a man who has lost his faith. Ed, Marshall and I wanted him to be an extremely vulnerable figure, not a stock movie hero. We tried to write him as a lost soul, searching to find his way. Only through his interaction with the Samurai and his growing respect for their warrior code does he find his proper place in the world.”

Herskovitz, who soon joined the writing team, adds that while the story and characters are purely fictional, the filmmakers painstakingly endeavored to achieve an overall level of authenticity in all aspects, “a faithful evocation of that period in Japanese history and of the principles and values of the Samurai. We tried to be accurate and respectful. We consulted experts, established contacts with academics and screenwriters in Japan and enlisted many Japanese specialists and personnel as part of the production. We wanted to get it right.”

As for the themes running through The Last Samurai, Herskovitz believes they are not only genuine but timeless. “The story about an individual who must come to terms with his loss of honor and self, and his subsequent journey to reclaim that honor, to trust himself again to make the right decisions, but certainly now, when we are surrounded by the compromises of modern life.”

As The Last Samurai unfolds, audiences experience the physical, emotional and spiritual turbulence of this exotic and contradictory era through Captain Algren. Says Zwick, “As he discovers it, so do you; as he is moved by it, so are you.”

Research Meets Action

Longtime writing and producing partners Zwick and Herskovitz, who have successfully collaborated for years on award-winning television shows and movies, were pleased to find in Tom Cruise a kindred teammate for making The Last Samurai.

Says Herskovitz, “Tom threw himself wholeheartedly into the preparation. I’ve never seen an actor do as much research for a film. He had a library of information and was amazingly helpful. Ed and I have always challenged each other, that’s the center of our creative relationship, but it’s rare for us to be stimulated in a similar way by someone else. Tom became a part of our creative partnership and it’s been incredibly enjoyable and rewarding. He has such a positive attitude and his ideas are always sound and often inspired. He continually pushed us in the most supportive way as we worked on the script and that spirit continued throughout production.”

Part of the actor’s preparation involved months of rigorous training for scenes involving hand-to-hand combat, riding and double-sword fencing, prompting Herskovitz to attest, “He worked several hours every day for about a year with a dedication and a discipline that was totally Samurai. He can handle the two swords beautifully and he’s a great horseman.”

“I worked for eight months to get in shape for this picture,” the actor confesses. “I learned Kendo [Japanese swordsmanship], Japanese martial arts, all manner of weapons handling. I not only had to ride a horse, but I had to effectively fight while riding. I studied Japanese. As far as training goes, you name it, I’ve done it.”

Legendarily focused and dedicated, Cruise continued his research and training throughout the production. Zwick gave Cruise several books on Japanese history and culture to add to the actor’s own growing library, and between takes it wasn’t unusual to find him reading a volume like the classic Civil War tome The Killer Angels.

Cruise typically arrived on set two hours in advance of the other cast and crew to hone his physical skills. His dedication paid off in enabling him to perform all of his own stunts, from several nights of double-sword fighting against multiple opponents to five days and one night of fending off murderous Ninja intruders, to weeks of martial arts drills opposite his Japanese co-stars and finally two months of relentless battle sequences.

“Initially I was concerned about achieving realism in the fight scenes,” says Cruise, noting that while he came into the project at a high level of physical fitness he was unfamiliar with the specific rigors of Samurai martial arts. Focusing on flexibility and gradually lowering his center of gravity with daily workouts enabled him to execute the naturally fluid moves “without stiffness.” Indeed, afterwards, Cruise mentioned that even his breathing had become deeper and he had a “clearer sense of awareness, of mind over body,” which he credits at least partially for seeing him through some of the more intense battle scenes without injury.

At times, observing his star’s commitment, Zwick wondered if he was expecting too much. “I thought, ‘what am I doing,’” he says. “Here I have Tom face down in the mud, getting the crap kicked out of him, or we’re doing take after take in which actual aluminum swords are swinging past his face at extraordinary rates and I think maybe I’m putting him too much at risk. But each time he would say, ‘just give me the time and the preparation and tell me what you want me to do, and I’m going to be there.’”

In truth, Cruise, a naturally gifted athlete and all-around sports enthusiast, looked forward to his character’s physical contests. In an inspired bit of scheduling, before Cruise embarked on his nights of double-sword combat, he split the shooting day by beginning with emotionally charged scenes between Algren and his Japanese captors. This combination of emotion and action echoed Algren’s own bifurcation; at once, a conflicted, conscientious man, struggling to reclaim his honor but also an impassive, strategic, lethally effective soldier. While Algren’s profound and complex emotional nuances intrigued Cruise, upon completing these scenes he happily and literally ran to the next sets, eager to begin his Samurai fight sequences. “I’ve wanted to do this since I was a kid,” he announced the first night, and he did not disappoint.

The parallels between Algren’s experience in the Samurai camp and Cruise’s training for the role were not lost on the company. “The training Tom did was not just an actor practicing to do stunts for a movie,” explains Zwick. “There’s a very significant correspondence between the training in martial arts and philosophic dedication Algren gets as a Samurai prisoner and the kind of training that Tom was undergoing both mentally and physically. He was preparing for the role itself, not just for the stunts or the fight scenes.” Cruise agrees, adding that, “I started feeling like Algren in the village, I got a sense of the kind of emotional and physical transformation he was going through.”

For Ken Watanabe also, working on The Last Samurai inspired a fair amount of soul-searching, even though the project placed him on somewhat familiar ground. His Japanese film career includes roles in several historical dramas, including the popular NHK Samurai series Dokuganryu Masamune and the feature Bakumatsu Junjyo Den, set against the waning days of the Tokugawa Shogunate when the Samurai held sway. Even so, Watanabe reveals that working on The Last Samurai encouraged him to examine more closely his own feelings about his country’s renowned warrior class and that it was partly Zwick’s passion for the subject that ultimately helped him understand Katsumoto and help bring the Samurai warrior to life.

“In the beginning, it was difficult for me to grasp the character,” he says. “What does he want, what is he thinking? Certainly there is beauty in death, traditionally, but dying, to me, is not necessarily a virtue, so it was hard for me to reconcile at first. As a Samurai and as the leader of his people, Katsumoto has a very specific way of living and dying, but I couldn’t help wondering, what right does he have to lead his people, the villagers and the people surrounding him, towards certain death with him, how could this be justified and allowed? It was a dilemma for me at first, until I realized that for Katsumoto it was not a question of life or death that was important, but a question of honor.”

Like Cruise, Watanabe trained intensely and performed a majority of his own stunts. “Katsumoto always carries two swords,” he says, “so I had to learn how to use them simultaneously. We wanted everything to feel real, including the fights. It was tough, but the motivation was strong. Before shooting each battle scene I had to yell to more than 500 soldiers. I yelled so many times that I lost my voice.”

“It was a complex role and Ken delivered a performance of deep emotionality, humor and great poise,” Zwick responds. “I cannot imagine the movie without him.”

As a counterpoint to the film’s extraordinary action sequences, The Last Samurai offers a number of deceptively quiet scenes. In his early days as Katsumoto’s prisoner in the Samurai village, in his silent but intense exchanges with Katsumoto and the other Samurai, Algren is forced to communicate without dialogue in circumstances where words are impossible – and ultimately unnecessary.

As Zwick points out, the absence of meaningful dialogue does not diminish the depth of these encounters. “The scenes in which Algren is getting to know Taka, this woman who looks after him every day and doesn’t say a word, are very powerful. Here are two people forced to be in each other’s lives and yet there are barriers between them – the circumstances, the natural restraint given the difference in cultures, and of course, the language. There are so many obstacles to their connection, yet they connect. It’s really a delight for me to see how much Koyuki is able to convey in her look, her gestures and her bearing, and how much Algren understands. It’s almost like a silent movie performance.”

The director’s commitment to explore his characters’ inner drama is perhaps best described by his early advice to Watanabe in a scene where they were trying to “get inside of Katsumoto’s mind,” as the actor recalls. “Before shooting, Ed said to me, ‘You have to feel everything – the campfire, the sound of insects, wind, temperature. It’s a cold night. Hear the horses stirring. Tom’s breathing.’ And all of this for a scene in which I had no dialogue. In a way, it was more like direction for living than for acting, which is a good example of Bushido spirit. Bushido is like breathing, being aware of our connection to nature and to everything. The Samurai don’t talk, they simply live it.”

Indeed, Zwick’s own work on the picture often crossed into the realm of a silent movie performance as he sought to convey direction across an ever-present language barrier while filming in Japan and later in New Zealand with hundreds of Japanese cast and extras. “When you look at the scope of the film, and think about how every single performance is important, every single moment is important to the whole, you’re amazed,” says Cruise, “at Ed’s ability to communicate effectively as a director to people who might not speak any English at all and still get the performances he wanted.”

Logistically, the director faced numerous challenges, all of which he ultimately took in stride, acknowledging the scale of the picture, its cross-cultural nature and the number of location shoots. “Just looking at the battle sequences,” he recalls, “I remember thinking, ‘we’re going to need how many men in this scene?’ and realizing, all of a sudden, the enormity of pulling that together. Not only do we need these men but they must be good actors, effective on camera, and then trained for battle, trained in martial arts. How many translators will we need?”

What he happily discovered was that “so many of the extras we found already had some martial arts training and were eager to demonstrate those skills. It’s been awhile since Japanese-style fighting has been on the screen. The Chinese martial arts have had exposure in a lot of popular movies in recent years, and even in the kinds of wire work that has inspired, but the disciplines practiced traditionally in Japan have their own brilliance. In a way, many of the actors saw themselves as ambassadors, able to showcase this style to a worldwide audience. They were excited to be part of this, and we were immensely grateful to have them.”

International Casting

“We made a leap of faith in the writing stage that we would find Japanese actors to play so many principal roles,” says Herskovitz, no novice when it comes to casting. “Whenever you find the right actor it’s miraculous, but when you find several right actors, it’s even more so. Ken Watanabe is incredibly captivating; you see in his face power, compassion, humor and sadness. Koyuki, who plays Katsumoto’s sister Taka, came in with the gravitas necessary to portray the sense of responsibility and the dilemma her character faces. Hiroyuki Sanada, who plays Ujio, is a major star in Japan. In lesser hands his part would just be seen as a simple antagonist but it has become so much more nuanced because of his performance. It’s like we found the Dream Team.”

For Cruise, interacting with the Japanese cast helped bring to life some of the texts he had been studying. “When you talk with people about their culture and they bring you into it, give you their own personal insights into the history,” he acknowledges, “it goes beyond anything you can read in a book.”

Cruise’s unflagging esprit de corps set the tone for the production, and was the first thing that Ken Watanabe noticed about the American star in their initial meeting. “We had our first rehearsals in Los Angeles and it might have been overwhelming for me, but Ed and Marshall and Tom made it easy,” recalls Watanabe. “It was a theatrical kind of rehearsal; we improvised a lot, explored how Katsumoto and Algren lived and the evolution of their relationship. I come from the theater, so it was a very reassuring way to begin. Also, it’s not often in Japanese films that I could help develop the character in that kind of creative atmosphere.” Regarding his high-profile colleague, Watanabe says warmly, “What a nice guy! He came to those early rehearsals in jeans and a t-shirt and helped set the tone for a very open, relaxed setting. His attitude was, ‘let’s make a great film together.’”

The bond that soon grew between Watanabe and Cruise proved helpful in later scenes where, as Zwick points out, “They had to trust each other because they were swinging swords within inches of each other’s faces – real aluminum swords.” As Watanabe jokingly puts it, “The timing had to be perfect; one miss and that would be the end of the movie.”

Commenting on the give-and-take the two actors developed, both physically and mentally, Zwick remarks on how important it was to the story for Katsumoto to prove a formidable match for Algren, “to be his rival and equal in every aspect. Without that balance, the movie would have faltered and tripped.”

Herskovitz agrees, saying that, “If you don’t have a great Katsumoto, you don’t have a movie. As powerful as Tom is as Captain Algren, he must have someone to play against. We felt some trepidation over casting the role initially and did a fair amount of searching before we came upon Ken Watanabe. When we met him we knew instantly that he was the one. It wasn’t just his look, but his manner, his bearing and charisma.”

Watanabe particularly enjoyed the confluence of East and West that the production fostered, both on and off camera. “It was interesting,” he says, “the juxtaposition of Japan and the West getting involved historically and also literally, in terms of this film – an American director and actors with Japanese actors and crew. We all learned from each other.”

Indeed, highly skilled and impressively credentialed Japanese professionals filled key positions behind the camera. “There are people on the crew who have devoted their whole lives to the presentation and celebration of the Samurai culture,” says Zwick. “There’s a whole film industry in Japan based on Samurai movies and some of our production team even worked with Kurosawa. They bring what they have studied and researched their whole lives as artists, prop men, set decorators, costumers or actors. It’s not as if we’re trying to imitate one of the Japanese Samurai movies; we are trying to do something uniquely our own, and yet to feel invested in that tradition is very important.”

Hiroyuki Sanada attests that he and his colleagues were equally impressed by Zwick’s work and look forward to his interpretation of their country’s history. “He really knows this subject, we are truly amazed,” says the actor, who plays consummate warrior and Algren’s potential nemesis Ujio. “He appears captivated by the spirit of Bushido and this era, which is rarely depicted even in Japanese movies. He has a respectful but fresh perspective and I hope that this will be a new discovery for Japanese films.”

Sanada, who began acting and performing his own stunts at age 13, has applied his talents in over 50 Japanese films, including the popular Ring thrillers. Famous not only for his acting and stunt work but for his brilliant swordsmanship, he has played innumerable Samurai and so served as the film’s unofficial consultant, working with stunt coordinator Nick Powell to choreograph the Kendo drills and various martial arts Katas, or ritual routines. Both on and off-screen, he served as leader of Katsumoto’s cadre of Samurai, men who Powell hand-picked in Japan.

As Ujio, the Samurai sword-fighting master, Sanada frequently sparred with Cruise and found him to be a worthy opponent. “Ujio is the most old-fashioned of Katsumoto’s Samurai,” says Sanada. “He particularly dislikes foreigners, resists foreign culture and especially loathes Algren, who is brought to his village as a captive. However, through swordsmanship, a bond is born between them. Because Ujio is the best swordsman in the village, the duels between Algren and Ujio had to be convincing, had to be intricate and dangerous, and we devised routines that, we hope, conveyed that. Tom was a great collaborator and I was very impressed by his skill and concentration and his willingness to try anything that was right for the scene.”

Additional significant roles were cast with highly regarded Japanese actors. Seizo Fukumoto, who plays the Silent Samurai, is an alumnus of countless Japanese Samurai films and known for his expertise at Kirareyaku roles (a Samurai who often dies at the hands of the hero), and postponed his retirement to participate in The Last Samurai. Masato Harada, who portrays the scheming businessman Omura, proponent of modernization and foe of the Samurai, is a respected and award-winning film director of worldwide renown. Shichinosuke Nakamura, who portrays the young Emperor, comes from a family of Kabuki performers and has appeared in numerous roles on international stages. Koyuki, as Katsumoto’s dutiful, conflicted sister Taka, is a successful model and actress who has several popular television dramas to her credit. Shun Sugata, who plays the loyal Samurai and jujitsu master Nakao, recently appeared in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill, following numerous starring roles in Japanese films. As Katsumoto’s son Nobutada, who befriends the captive Captain Algren in his father’s Samurai compound, kung-fu expert Shin Koyamada makes his feature film debut in The Last Samurai. His character’s particular specialty is the bow and arrow, for which he practiced for months under the tutelage of Koji Fuji, another of the onscreen Samurai but also a bona fide master archer and a no-nonsense coach.

Continuing in an international vein, the filmmakers cast Londoner Timothy Spall in the starring role of displaced Brit Simon Graham, who serves as Algren’s interpreter upon his arrival in Tokyo; Glasgow-born Billy Connolly, as Algren’s friend and comrade-in-arms, Zebulon Gant; and native Californian Tony Goldwyn as Col. Bagley, a former Civil War officer seeking his fortune in Japan.

“Tim Spall is a gem,” declares Herskovitz. “His character is much too idealistic for his own good and Tim brings a humor and wit to the part that is incredibly endearing.”

“Because Algren’s journey is so personal,” offers screenwriter John Logan, “we gave the audience an interlocutor in the character of Graham, a lens through which to view him.” Indeed, Spall’s character, Simon Graham, serves initially as Algren’s main conduit to all things Japanese and also serves, to some extent, as the story’s narrator. He is the quintessential Victorian expatriate, dressed in a hat and suit. For all his proper attire, though, Spall recognizes him as “a true misfit.”

“He’s one of those people,” the actor elaborates, “often found in a country foreign to them. They live there because they’re misfits to a degree in the country they’re from.” Or, he quips, “They might be the third son of a minor aristocrat and nobody knows what to do with them. In any case, Simon Graham has found himself in Japan attached to a 20-year-old British trade mission. Meanwhile, he’s grown to genuinely adore the culture and knows more than anyone how it’s changing.”

For his part, the English actor mastered several lines of Japanese dialogue phonetically, a feat he shrugs off with characteristic humor, but notes that nothing gave him more trouble than the camera used for his character’s photography hobby, an actual 19th century relic the prop department found on eBay. “Ah, the camera,” he recalls with a shudder. “That’s when it got a bit difficult, doing the Japanese and operating the Victorian plate camera simultaneously. It’s like rubbing your head and patting your stomach. Don’t know how I managed it.”

Spall adds that, in fact, several famous expatriate photographers lived in Japan during the Meiji Restoration and says that Zwick steered him towards one in particular. “Ed is the most well-informed director I’ve ever worked for,” he says. “There isn’t an aspect of this era that he doesn’t know about. I think he gave everyone a book that their character might be based on or influenced by. Mine was about a chap named Lafcadio Hearn, an American in Japan around this time who, like Graham, is completely taken by the culture.”

Billy Connolly stars as Zebulon Gant, a character he considers “the archetypal non-commissioned officer who has license to be impertinent with his superior Algren because they are old friends. When Gant is hired to train Japan’s modern army he tracks Algren down to get him involved too, because they’ve both tried civilian life and they’re no good at it.”

Connolly found The Last Samurai to be “a great story, a very heroic tale,” but it was his personal interest in Japan that also attracted him to the project. “I read a great deal about Japan and had been there a couple times. I love the culture,” he says, “and thought Ed and Marshall got it exactly right. They obviously have a great respect for the traditions and sensibility they’re portraying. I’d always thought that tales about the Samurai would make a dramatic subject for modern film. I believe audiences will be impressed by the loyalty that the Samurai have for each other and the allegiance between Algren and my character, Gant.”

One of the UK’s top comedians, Connolly’s career has expanded into television and film, and he’s adding dramatic roles (notably 2002’s White Oleander) to his award-winning comedic performances. Says Herskovitz of the two-time BAFTA nominee, “Billy Connolly is one of the funniest men I’ve ever met and just a joy to watch.” Regarding the actor’s casting, he says, “Ed and I always loved watching Victor McLaglen in the John Ford films, all those cavalry films with John Wayne. McLaglen would play the second in command. He was an Irishman playing a Scotsman and partly as homage to that we hired Billy Connolly, a Scotsman to play an Irishman.”

Tony Goldwyn, so memorable as the charming but traitorous villain who pursues Demi Moore’s character in Ghost, delivers a thoughtful and effective portrayal of Col. Bagley.

From Algren’s point of view, Bagley is evil. Algren vehemently disagreed with Bagley’s decisions during the American Indian Wars and now, as he grows to admire the Samurai, Bagley’s allegiance to the opportunistic and anti-Samurai businessman Omura confirms Algren’s negative opinion of his erstwhile comrade-in-arms. To the filmmakers, the Colonel might be less evil than just typical.

“Ed and I talked about making him very much a man of his time,” offers Herskovitz, “because, in fact, his outlook was the norm. Algren is more in tune with indigenous people, with the American Indians and later with the Samurai. That type of thinking is an anathema to Bagley, who’s a pragmatist and an empire builder, someone who believes without question that Western civilization is superior. He believes that the elements of American culture he helps bring to Japan – everything from munitions to democracy to a free market system – are gifts that this backward nation should gratefully accept. From a moral and philosophical perspective, Algren and Bagley come from completely different places.”

“He’s not a whip-cracking villain,” adds Zwick. “Bagley’s racism is undeniable but it’s unconscious and wholly appropriate for a man of his time, which is a subtlety that Tony conveys. It’s a very brave performance.”

It was precisely that subtlety that drew Goldwyn to the part. “What fascinates me is moral ambiguity and that’s why I find villains often interesting to play,” he says. There is a gray area to everything, particularly in war. In trying to affect a certain doctrine or solve a perceived problem, negative results occur and Bagley personifies all that and it’s very interesting to explore.” On a more physical note, Zwick says, “he’s also a hugely talented horseman, which was a good thing because I had to put him into a situation where he was riding a horse through explosions and gunfire and he just nailed it.”

Locations and Sets

To help infuse a sense of tradition and Japanese culture into the project, Zwick began production in a small Japanese town called Himeji.

The Last Samurai is the first film to shoot in Himeji, but the village boasts a much more impressive landmark in the form of the Engyoji Temple and Monastery, the production’s first shooting location, which served as the country residence for Katsumoto and his loyal followers. A sprawling complex of graceful hand-hewn wooden buildings nestled high in the mountainside and graced by a forest of bamboo, Chinese elm and cypress trees, it was a unique and breathtaking spot.

“The Engyoji Monastery was built around the year 900,” says Zwick. “It’s a sacred place, first built to train monks and now a shrine where the Japanese make pilgrimages. The monks were enormously kind and gracious in allowing us to photograph it and them. Since the film tries to address the more spiritual aspects of the Samurai, it was a special place to begin production and really clarified the heart of the film for everyone. There is no way we could ever replicate something like this. You feel the past in every piece of wood, in the scent, the way the light hits, the way the stones have been polished from thousands of years of people walking on them and praying here. I think it was important to have endowed the film with the spirit of this extraordinary place.”

“Making that initial, physical connection with such an impressive historic site really helped everyone on the crew, Japanese and American alike,” offers Herskovitz, “to better understand what we were trying to achieve.”

Filming at the monastery posed an unusual challenge for the company. Because of its location atop Mount Shosha, cast and crew traveled up the wooded mountainside via suspended gondola, which was the only alternative to a well-worn footpath.

Being especially careful to avoid damaging or altering the ancient structures in any way while shooting interiors, the production used full-sized opaque screens to serve as “walls” if they needed to change the dimensions of a room.

Following their shooting schedule in Japan, the production used additional sets and locations in New Zealand and on the Warner Bros. Studios lot in Burbank, always striving to recreate the look and atmosphere of late-1870s Japan as authentically as possible. Research was extensive. Starting months before filming began, production designer Lilly Kilvert and her team logged hundreds of hours poring over books, photos and documents about the Meiji and prior periods, as well as consulting with experts about fabric, building materials and even about what kinds of foliage would be likely to adorn a Samurai home’s front yard.

Nearly every item and set in the film was made from scratch by the production, from the thatched-roof homes of a rural Samurai village to a congested, modern Tokyo thoroughfare; from silk-shaded lamps and rice paper window screens to period flags. They even made their own trees…

Used primarily in the garden of Katsumoto’s Tokyo home, in the Temple courtyard of his country residence, and to augment a natural forest bordering the great battlefield, more than 150 individual cherry trees were built by the production. Constructed as wooden trunks on portable stands, each tree had sets of removable “seasonal” branches so it could be dressed for spring, winter, summer or fall – often changing within a single day of shooting.

Kilvert, an Oscar nominee for her art direction on Legends of the Fall, adapted an existing set on the Warner Bros. Studios backlot in Burbank perhaps best known as Waltons’ pond, from the 1970s television series The Waltons, and also used for Gilligan’s Island, to create Katsumoto’s Tokyo residence. The ready-made lagoon was transformed into a reflection pond alongside Katsumoto’s house but the house itself had to be built in its entirety as well as a bridge spanning the pond and serving as a planked path to the front entrance. While not a replica of a specific building, the architecture and materials were based on traditional design and standard dimensions for a proper Samurai or upper-class residence.

This set involved ingenious mobile platforms allowing for a wide range of camera movement, including one mounted on a huge crane. As the site of an important skirmish, Katsumoto’s home had to be sturdy enough to sustain the action but breakable enough to depict the damage realistically. As Kilvert acknowledges, “My work is not entirely about the design, it’s about the workability of the situation. If we anticipate an action sequence, we map it out and decide how much of the set needs to be break-away and how much needs to be sturdier, how many takes we might need and so on.”

Meanwhile, within shouting distance of Katsumoto’s backlot residence, the production designer created a 19th century Tokyo thoroughfare on the Studio’s famed New York Street, teeming with shopkeepers and patrons in kimonos bartering for food, housewares and fabric as visiting Westerners perused their wares and the more exotic sights such as rickshaws and Geishas borne in opulent palanquins. Delicate Japanese screens and lanterns intermingled with new brick buildings and telegraph wires crossed under prayer flags, as the traditional society began to integrate more modern and distinctly Western influences.

“This area that became known as the Ginza district had to encompass about a year’s worth of change, from 1876 to 1877,” Kilvert explains. “Japan was going through a major transformation at this time, as all the European nations moved in to establish a foothold in what they assumed would be a lucrative market. Everybody was there – the English, French, Spanish, Germans – you heard many languages and we reflected that in the signs on the buildings.” Often, that meant seeing the anomalous spelling “Tokio” on storefronts, which Kilvert faithfully reproduced.

Kilvert adds that Japanese-style buildings still dominated the Tokyo street because “architecture changed more slowly, as it tends to do,” but that Western-style red brick construction was becoming a more common sight. “Even now, if you go to Tokyo’s Ginza district you see the remnants of these buildings. Later, they discovered that this material didn’t suit the climate at all but for a while they were all the rage.”

Most of the buildings on set were plant-ons, facades grafted to the existing New York street structure, made mostly of sturdy, contemporary materials such as wood and fiberglass tiles. However, the doors, screens and lanterns plus some of the boxes, chests and baskets were all Japanese antiques found in Los Angeles and Japan.

Kilvert also participated in the scouting expedition that ultimately uncovered a secluded 40-acre cattle and sheep farm in New Plymouth, New Zealand, on which to construct the film’s self-sufficient 19th Century Samurai village. A 200-member crew that included local carpenters then converged to create a total of 25 structures from the ground up, as well as fences, gates and animal pens. “Mostly,” as Kilvert recalls, “in the pouring rain.”

To facilitate revealing shots the crew cut horizontally into bordering hillsides and built on multiple levels, moving upward more than outward and providing depth. Lumber was brought in by helicopter; thatch from a nearby valley was cut and hand-tied; and crops planted. Fabric was dyed and fashioned into a series of large flags that would identify the village by its Samurai clan name. With the exception of a small number of props and lanterns imported from Japan, every item in the completed village was made by the crew, using local sources. Beginning five months prior to the arrival of cameras, greenskeeper Stephanie Waldron and her team took on the tough terrain to make rice paddies and plant trees and crops.

Kilvert designed her village with the precision and pragmatism of a city planner. “We had a potter’s building complete with baking kiln, a weaver’s house, a basket maker, and – this being a Samurai village – a swordsmith and a shrine where, among other things, the blades would be blessed,” she recounts. “We also had a water wheel and cistern system, since the Japanese had advanced methods of water delivery and irrigation at the time. Essentially, we designed the village based on the type of people and occupations that would have existed then.” With the exception of Taka’s home, all the village structures were empty shells and so served as effective shelters for the cameras, lighting and sound equipment.

That monumental task accomplished, the crew then duplicated their work on a number of soundstages, to allow the director both indoor and outdoor shooting opportunities. New Zealand also provided the panorama for the film’s climactic battle scene – but only after the production reduced an adjacent hill by approximately 50 feet in height and 400 feet in width to create a wider field. Trees, both real and artificial, were brought in to supplement the background forest and battle flags bearing Samurai clan names were made. A team of 25 greensmen remained on hand during filming to repair damage sustained by the landscape from horses, men and simulated artillery after every major take.

“What Lilly has done on three continents is phenomenal,” Herskovitz acknowledges. “Recreating period Japan on the backlot, building an entire village on the top of a mountain – it’s like going to war. We were moving armies and material on a colossal scale for a company making a movie.”

Kilvert attempted to be as true to the era as possible and strove to depict historical authenticity within the context of the story. “The most difficult thing we had to do in designing this film was to find a way to honor the rules of Japanese architecture while finding ways to make them photographable,” she says. “Much of it is very precisely designed. The length of a tatami mat and the height of a shoji screen are specific measurements. In the end, we had to break some of their specifications. In general, I tried to assemble the essential elements and create an authentic feeling of a particular time.”

Costumes

In addition to sets, authentic costumes helped establish the on-screen world of Meiji Japan and this responsibility fell to costume designer Ngila Dickson.

Simultaneously leading crews in Japan, Los Angeles and her native New Zealand, Dickson supervised the creation of hundreds of costumes made exclusively for the film, based on historic photos and documents as well as interviews with scholars of the period. Her research uncovered essential details from the method of handcrafting Samurai battle armor to the cultural significance of the color, fabric quality, print-size and sleeve length of a kimono.

Dickson, whose designs earned a BAFTA Award and a Saturn Award for Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers and an Oscar nomination for Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring, managed the herculean task like a general overseeing an army, a strategy she originated while working on the Rings films. “I put one coordinator in charge of each area – the village scenes, the Samurai armor, the Imperial Army, and so on,” she explains. “That meant I could compartmentalize and know that each of those team leaders would follow their specialty.”

Dickson approached the epic Samurai drama with a dedication to accuracy but soon discovered that much of her historical references were subjective. “The first thing we did was find every possible photographic reference for the period and amassed an enormous volume of images,” she says. “As we went further into it, we realized that many of those images were staged and that the photographers had taken quite a bit of license. We discovered that in some cases they were using the local prostitutes and dressing them up. So, from what we initially thought was a huge historical reference, we had to go through and re-evaluate. Ultimately, we interviewed expert historians both in America and Japan and then cross-referenced their material. Finally we looked again at the photographs and began to unravel the truth.”

Once Dickson felt comfortable with the body of images she began to make the wardrobe. Because costume houses don’t stock immense supplies of Meiji period kimonos or Samurai armor, her team bought the raw materials and created what they needed. “Once we established the elements for the kimonos we started making our own,” she explains. “We had people making screen prints so we’d get the stripes right and over-dyeing fabric to reproduce the color of the period. We started with a basic look and then built on top of it. For me, that’s a good way of achieving a good period quality for the costumes.

“I’m a demon when it comes to proper color,” the designer admits. “Most people think of Japanese dress as quite colorful whereas I’ve used rich, dark, subdued colors, which are correct to the Meiji period. I use brights very sporadically, for specific elements, such as Geisha. As with every movie, we try to distinguish one character from another with wardrobe selections. Ken Watanabe’s character, the Samurai leader Katsumoto, is about purity and strength, and embodies a Zen-like quality, so he appears mostly in deep blues and earth tones.

“Likewise, Taka is initially associated with very dark tones,” Dickson continues. “Taka is a subtle, complex character, a woman whose husband has been killed in battle by the man she is currently nursing back to health. We began with a very rich, dark palette for her, in costumes as plain as possible. As the story progresses, Taka’s colors lighten as she begins to blossom and change with Captain Algren’s influence. Of course, the clothes of that time were very restrictive so her wardrobe can never be very vivid; the progression is subtle.”

Dickson found a wealth of resources in Japan and, appropriately, much of the wardrobe was made there. “We found that going to the local markets was worthwhile because what tourists buy there wasn’t at all what we were looking for and we got a very warm response from the vendors,” she recalls. “They couldn’t believe what we were buying! We found a lot of original fabrics still on rolls. Although they were fragile and old they provided another blueprint. Interestingly, the 1930s style of kimono dressing in Japan had similarities to the Meiji period, so we were able to rework some of that material as well. All our lead costumes were made in Japan. I designed them, then they went to Japan to be fabric-swatched and hand-sewn, which is the traditional way of making kimonos, haori [the half-jacket worn over a man’s kimono] and hakama [pleated loose-fitting trousers].”

Through amazing good fortune, Dickson encountered two people in Japan who became an important part of the wardrobe team and “who helped keep us honest,” she says. “Akira Fukuda, a very well regarded costumer in Japan who worked with Akira Kurosawa, joined our department, and we consulted with Munehisa Sengoku, the master of court costume and custom to the Imperial family in Japan. If the Imperial costumes in the film seem authentic, it is because of the depth of knowledge of these two men.”

Senguko even volunteered to have his school, the Takakura School, Institute of Court Culture, make two costumes for a key scene in the film: one for the Emperor Meiji, on which he and Dickson collaborated since it would not have been a garment the emperor would ever have worn publicly, and one for Katsumoto, made to Dickson’s design. The Emperor himself was subject to specific guidelines regarding his wardrobe, whether formal or casual, and so the manner of his dress could indicate at a glance the nature or tone of a particular meeting. In this scene, he receives Katsumoto in a white silk kimono and red hakama, a casual garment which suggests the level of intimacy that exists between these two men regardless of their current differences.

Acknowledging the chrysanthemum as a symbol of the Emperor’s family, Dickson also made sure that that a chrysanthemum emblem ornamented the sleeves of the otherwise utilitarian uniforms of the Emperor’s Royal Guard.

As a Civil War veteran, Algren is introduced wearing the Union’s blue uniform. Dickson also made a long, chocolate-brown suede coat for him with a distinctive Western feel, reflecting his days on the American Indian Campaign. The coat, though not lightweight, was supple and roomy enough to move with his body when a scene called for him to fight.

“Tom is a very physical actor,” she notes, “and it was important for him to feel as comfortable as possible. The Civil War uniform posed no problem; it was already designed for fighting. As for the leather coat, we needed something that would allow him to travel from the Civil War through the Indian Campaign and then to Japan and that also suited his character and history. I specifically didn’t want one of those Custer-style jackets. What we ultimately ended up with was a deerskin, mahogany, very weathered and aged, as though it had survived a lot. The instant Tom put it on, it was hard to imagine him without it. The bonus, which we discovered when rehearsals began, is that it had great flexibility.”

Dickson also dressed the Samurai for battle, staring with a trip to “Japanese armor houses and museums. We couldn’t hire Samurai armor because it would be destroyed during filming, which meant we would need to make it ourselves. We learned the intricate details of making real Samurai armor – how it was stitched and laced,” she reveals, “and constructed the pieces in New Zealand.”

The process of producing 250 sets of armor began by first assembling the many individual pieces. Jewelers were employed to fashion prototype plates in copper, which were then reproduced in softer metal and laced together over a model to test for form and drape, and ultimately molded and sculpted in eurothane. Similarly, blacksmiths created models for the helmets. Jewelers also applied their talents to the myriad details characteristic of Samurai armor, such as decorative discs and symbols, filigree, grommets and rivets in the form of chrysanthemums and other flowers because Samurai craftsmanship was like jewelers’ craftsmanship – very fine quality, and rich in detail.

Reproducing chain mail for the lead costumes presented another challenge, ultimately solved by contacting spring manufacturers who supply engineering companies. Armed with pliers, dedicated workers then spent approximately three months manipulating the links into appropriate 4 or 6mm rings. For background players, sheets of chain mail were obtained from India and cut to size. Once in hand, attaching chain to fabric required hand-stitching. Equally labor-intensive were the costumes’ collars, made of a fabric base with hexagonal metal plates attached through a layer of silk, which had to be of a certain quality to accommodate thick cord lacing, and then hand-stitching in a honeycomb pattern around each plate. Each collar took about 30 hours to make.

Finally, after holes were drilled and the various panels of armor laced together, then lacquered multiple times to achieve the right color, workers carefully chipped and scratched the plates to reveal the layers underneath and give each piece a history so that it would not appear brand new.

Originally designed for flexibility, with panels that move with the body, the Samurai armor required little modification for onscreen action and Dickson was able to make the hero costumes comfortable for stunts without compromising the visual antiquity. Although, historically, the armor might have been more colorful, Dickson de-saturated the tones to be consistent with the film’s palette, explaining that, “Traditionally, Samurai armor was individual and idiosyncratic. We tried to incorporate elements that best suited each character. For example, Katsumoto’s battle dress, a black outer shell over an elaborately embroidered black, gold and gray kimono featuring a pattern of his native valley’s flowers, is the most detailed and elegant, signifying his stature as a leader. It’s important that Katsumoto’s armor is perceived as ancient because this is his choice. In truth, he and his men would not be wearing Samurai armor at all during this period. But, in rejecting the modern ways, he has returned to the past and so donned this ancient uniform as a deliberate statement. We stripped out the color based on the point of view that this group of Samurai choose to wear their ancestors’ armor.”

Dickson’s 80-member team worked throughout a 14-month period to meet the film’s wardrobe needs. “Overall,” she says, “there were more than 2,000 costumes made, to cover scenes as diverse as a San Francisco Convention, the Japanese Imperial Army and Samurai on the battlefield, village life, flashbacks to the American Indian wars and Japanese street scenes.” She pauses to consider the math before concluding, “We had costumes coming out of our ears.”

The Troops

The company moved to New Plymouth, New Zealand, in January 2003, after a worldwide location search determined that this was the best locale in which to replicate certain 19th century Japanese vistas.

“Aesthetics is a very important part of the culture, particularly the natural aesthetic, the land,” says Zwick. “One of the great tragedies is that there is so much less open land available in Japan today. Many Japanese come to New Zealand because of its beauty.” Citing the countries’ similar topography, he adds, “Because it’s a volcanic island not unlike Japan, we hoped to embody here that aesthetic from an earlier age. The Japan we created is one of imagination in that it no longer exists, but I think we got as close as we could.”

The production scale was huge. Between 300 and 600 Japanese extras appeared in the film on any given day and 400 New Zealanders were employed in every department, from wardrobe to construction and set decorating to camera. The rest of the 200-300 crew members came from the United States, England, Australia and, of course, Japan – nearly every department included at least one Japanese representative as part of the working crew and/or as a translator. On days involving scenes with huge numbers of extras, the shooting crew numbered approximately 1,000 and work began at 3 AM for many of the hair, make-up and wardrobe personnel, who styled all the sculptural hair-dos, tied the kimonos, hakama and haori in the traditional Japanese manner and fit the armor.

This inundation of people and material was a new experience for New Plymouth, where the tourist trade caters mostly to surfers, backpackers and outdoor enthusiasts eager to tackle Mt. Taranaki in Egmont National Park or enjoy the uncrowded beaches of the Tasman Sea. The local Daily News assigned a reporter to track the filming and a radio station put up a $5,000 “bounty” for whomever could deliver a live interview with Cruise. The competition ended nicely when Cruise himself called in after a night shoot and matched the prize with the proviso that the entire sum be donated to a local school.

In the search for extras to appear as Katsumoto’s loyal Samurai, the casting department found 75 Japanese residents of Auckland, a five-hour drive from New Plymouth. Additionally, stunt coordinator Nick Powell hand-picked a group of novice Japanese actors to become his “core” Samurai. None were professional stunt men and only two could ride horses, but all were athletic and enthusiastic. After two weeks of rigorous training, they proved their mettle, shooting arrows and participating in complicated Kendo drills like experts and, in one particularly impressive display, riding horses at high speed down a hill while firing arrows with no hands on the reins.

The production next staffed the Japanese Imperial Army by finding some 600 extras in Japan and putting them through boot-camp to become a credible military force. They learned to march and drill, to handle and fire a rifle, to lunge, parry and thrust a sword, to work with a bow and arrow, and to manage “movie” hand-to-hand combat.

“Their dedication and motivation truly impressed me,” says the film’s military advisor Jim Deaver. “They came from all walks of life. Some were actors, some shopkeepers, drivers or college students but all of them were eager to learn, to represent their culture and their country and, to a great extent, their ancestors. Their progress was remarkable, considering that they began with very little English and quickly learned to respond to English and Japanese commands, to move from a skirmish back into platoon formation and how to route-step on a dirt road.” All this occurred during the summer heat, the sun glaring down on the grounds of the Clifton Rugby Field. A typical day began at 8 AM and in ten hours could include archery rehearsals, firearms instruction, sword training and an explanation of Bushido.

“What I may be most proud of,” Zwick continues, “is that no one got hurt,” which is always a consideration when filming action sequences of this magnitude, even when every safety precaution is met. “Likewise, none of the horses were injured – not a turned ankle, nothing. These were remarkable animals, so well trained and loved by everyone.”

The 50 horses were purchased by the production company in New Zealand and trained by an international team of instructors under Horse Master Peter White for four months prior to filming, under the supervision of a full-time veterinarian and a representative from the local chapter of the American Humane Association, Film & Television Unit. Based on individual ability and temperament, the equine actors were categorized by White as either “actor’s horses, stunt horses or background horses.” When the battle scenes wrapped, half the horses returned to their previous owners. Others remained with the local trainers who had served as their wranglers and grown attached to them during production, or were sold to residents of the New Plymouth area that White and his staff felt would provide them good homes.

In the company of their trainers and the actors they would be carrying, the animals, none of which had ever worked on a film before, were conditioned to take sound effects like gunfire and explosions in their stride, and the few that were required to fall in battle learned how to land in a way that would prevent injury. Additionally, Zwick confirms, “pits were dug in the mock battlefield, stuffed with padding, soft mulch and hay and covered over with grass so that when a horse dropped on cue it would have a nice soft bed to fall into.”

As the horses practiced, so did their riders. White singles out Tom Cruise and Tony Goldwyn as the only two equestrians of the group and estimates that another 6 or 8 riders had some experience but that none of them had ridden under the kind of busy, noisy and crowded conditions posed by filming. In two months’ time, integrating this intensive training into their already full schedules, these men learned enough about horsemanship to ride into Zwick’s battlefields with confidence.

Supplementing the action, Visual Effects Supervisor Jeffrey A. Okun (Stargate, Deep Blue Sea) employed CGI to add a rainfall of virtual arrows and the occasional fireball to the frenetic battle scenes. Says Okun, “A lot of times the Samurai have to ride horses while shooting arrows into a crowd of hundreds of people, and using real arrows would be too much of a safety risk, so that’s where we’ll put in the CGI. Likewise, if you see an arrow hit a horse, that won’t be real.” Maintaining that the most effective visual effects are those that remain undetectable, Okun says that CGI and green-screen techniques were also instrumentally involved in a scene in which the Samurai Ujio beheads a man on a Tokyo street.

Production took on the shape of a military event. Under the stewardship of the production’s “general,” Unit Production Manager Kevin de la Noy (Saving Private Ryan, Braveheart), the storyboards for what were known as the fog battle and the final battle became detailed, strategic battle plans. “Both the fog and final battles were about strategy and ingenuity,” says Zwick. “Any filmmaker approaching these kinds of sequences should study Kurosawa and in fact, I watched Ran again prior to filming Glory. But, ultimately, our battles are unique to this movie and specifically driven by the situations facing the Samurai and the Imperial Army. We had to consider how traditional warriors like the Samurai with no firearms would attempt to defeat a modern force with modern weapons.”

As the director points out, when the Samurai appear out of a mist-shrouded forest, descending upon the ill-prepared Imperial Army like ghostly demons, “the idea was that the Samurai would use the cover of fog for surprise, allowing them to attack swiftly and suddenly, at their discretion. There is also the psychological advantage of using the forest and the fog as cover, so that when they chose their moment to strike they would materialize as if out of nowhere, in their terrifying, ancient armor, with their legendary, lethal swords.”

Zwick based this tactic and those he employed in the final battle on several historical sources, including that of famed Samurai master and martial arts teacher Miyamoto Musashi, who is credited with inventing and perfecting the technique of fighting with two swords and wrote The Book of Five Rings, a spiritual and technical manual printed in 1645. Referencing Musashi: “There are three kinds of (martial) preemption. One is when you preempt by attacking an opponent on your own initiative; this is called preemption from a state of suspension. Another is when you preempt an opponent making an attack on you; this is called preemption from a state of waiting. Yet another is when you and an opponent attack each other simultaneously; this is called preemption from a state of mutual confrontation.”

Of the three, the fog battle exemplifies “preemption from a state of suspension,” as the ancient master defines it: “When you want to attack, you remain calm and quiet, then get the jump on your opponent by attacking suddenly and quickly.” The final battle illustrates Musashi’s second maxim, preemption from a state of waiting.

The fog battle takes place near Lake Mangamahoe, a public park known for hiking trails and fishing holes and the final battle, which took two months to complete, was filmed on a farm, with vast grassy fields and flanks of forest that provided the perfect location for various aspects of the action. The production carved out dirt roads to transport personnel and equipment along special, color-coded routes designated prior to filming. One area became base camp, another was a place for the horses and another was where the Samurai and Imperial Army players dressed and received their weapons. As in actual warfare, maps were drawn and positions assigned – Samurai here, Imperial Army below.

Surveying his battlefield for the first time, Zwick was momentarily awed. “It’s one thing to plan and imagine what you want on a film, but when you actually arrive and survey the scene there’s a moment of ‘Oh my God, what was I thinking?!,’” the director admits with good humor. “In truth, if we had not done as much preparation in the earlier stages we would never have been able to make this movie because there, in the thick of it, we had so little time to talk with 700 men storming over a hill and explosions going off.”

Supplying the action was a monumental weapons inventory, comprised of both traditional Samurai blades and arrows and circa 1800s firearms, meticulously restored by the production. Prop master Dave Gulick relied upon Japanese sources to ensure the proper usage of various kinds of swords, which was quite specific down to the way in which scabbards were tied and how a certain blade would be worn differently in battle or on the street. Gulick’s team purchased several high quality swords from a swordsmith in Japan as samples for pieces made for the film, as well as faux blades from the renowned Kozu prop house in Kyoto and from Shogiko Studios, the movie company famous for its Samurai films.

Meanwhile, weapons coordinator Robert “Rock” Galotti and his team tracked down vintage rifles and pistols from private collectors and sources around the world, then refurbished them – a process which includes stripping the antiques’ finish and “re-blueing” to its original shade as well as carving new wooden stocks, each a slightly different fit since the guns were made before the time of machine standards. One of the weapons Cruise carries onscreen in his shoulder holster is an authentic 1851 Navy revolver, a so-called cap-and-ball gun, that would have been used in the civil war.

To capture all the elements, Zwick and Oscar-winning cinematographer John Toll typically made use of multiple cameras. Perhaps their favorite rig was the crane-held camera, and Toll utilized all kinds – a libra crane, the Chapman and Giraffe and an impossibly oversized rig called the UFO. The graceful swivel and reach of these various cranes and cameras added elegant, classical movement to the shots while revealing the scope of the landscape and the emotion of the drama. In the final battle, Toll also used a longer lens and different camera speeds to capture the grit and emotion of the individuals fighting for the “new” Japan and those defending the old.

In the end, these foes have a shared respect of their common, dying past; despite the violence that ensues and this seeming paradox is the basis of what Zwick calls the “film language” of The Last Samurai.

“It seems to me that every movie has its own particular language and it usually evolves in the course of filming. It is at times a celebration of yin and yang and that manifests itself in images and movement,” offers Zwick, “as in the scene where Taka dresses Algren for battle – Algren, the warrior, for once is passive while she does this but she ends up kneeling in front of him in a traditional pose of submission. It is a love scene, there are definite sexual undertones, but not in the typical way. The kneeling position is also associated with prayer. In another scene Katsumoto, the quintessential Samurai, appears prostrate in front of the Emperor. There is a ritual, almost loving way a sword is handled; the Kendo drill, a martial exercise, is also a graceful dance. All these peaceful expressions of respect and dedication arise in a film also about violence and death. There is a lot of duality, as there is in the Japanese culture. These recurrent movements and ideas become the film language; I don’t plan them necessarily, they happen naturally.”

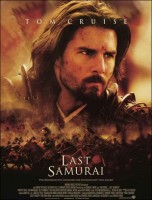

The Last Samurai

Directed by: Ed Zwick

Starring: Tom Cruise, Timothy Spall, Billy Connolly, Tony Goldwyn, Ken Watanabe, Hiroyuki Sanada, Shun Sugata

Screenplay by: John Logan

Production Design by: Lilly Kilvert

Cinematography by: John Toll

Film Editing by: Victor Du Bois, Steven Rosenblum

Costume Design by: Ngila Dickson

Set Decoration by: Gretchen Rau

Music by: Hans Zimmer

MPAA Rating: R for strong violence, battle sequences.

Studio: Warner Bros. Pictures

Release Date: December 5, 2003