The story hit the headlines immediately. The calendar was published and spread through Yorkshire, down to London and even across the Atlantic to Hollywood. The calendar was a huge story in all the British media, across Europe, and in the USA, where stories ran on the front page of the New York Times and on CBS’ 60 Minutes, the Today Show, and 20/20, and in People Magazine among others. Everyone everywhere wanted to know more about the courageous – and outrageous – women of the Rylstone and District Women’s Institute. The calendar was such a success that by early 2003 it had sold nearly 300,000 calendars, raising nearly £600,000 for leukemia charities. It also turned the women into national – and international – celebrities.

“We had no idea that we would get so much coverage when we launched the calendar,” says Angela Baker, whose husband John’s death inspired the calendar. “We just thought it would only appeal to our friends and family.”

The women could not have been more wrong about the impact of the calendar; and before long Hollywood came knocking at the door. Their story, combining heart-rending drama and gutsy determination, was a natural for the big screen. And yet it surprised the women when the offers started flooding in. Given the subject matter, the women of Rylstone were understandably cautious.

“The idea of a film was quite nerveracking,” explains Baker. “I thought it would be very hard on me and my family to watch our story unfold on the big screen; it was so very personal and I wasn’t sure I wanted anyone to Touchstone Pictures’ share it. I was worried it might be too intrusive coming so soon after John’s death.”

When producers Suzanne Mackie and Nick Barton and screenwriter Juliette Towhidi visited the women of Rylstone WI, it soon became clear that they had the women’s interests at heart. “Angela and Tricia really put us through our paces on the first meeting,” says Mackie. “We told them we were struck by it being a very funny story, but more importantly a very moving human drama and that the substance of story came from Angela’s husband’s death from leukemia. That’s what gave it depth and meaning and took it from being a jokey, frivolous story to a poignant and universal story.

“What also appealed to me was the fact that it was a woman’s story,” Mackie continues. “My initial reaction was, good on you, girls for having the guts to shout from the rooftops: `Just because we’re over 40 it doesn’t mean we can’t look beautiful!’ There’s a very strong sense of female camaraderie in the story, which I found enormously appealing. These women really support each other in every way.”

Once Angela Baker and Tricia Stewart were on board (“When I met Suzanne and Nick, we just clicked,” recalls Baker) the producers then began negotiations with the members of the group to secure rights to the individual women’s stories. Alert to how sensitive the issue was, they made several visits to Yorkshire to get to know the group and to assure them of their intentions.

It was in December 2000 that director Nigel Cole joined the project. ”We had a list of several directors, but we knew that Nigel would bring the right sensibilities to the film,” Mackie says. “He would allow the comedy to come out of the drama and create a characterled and emotionally layered film: a human story both funny and poignant.”

“It’s pure coincidence that both films I’ve directed are about women,” Cole says, “but I do like working with women. I won’t ever be a man’s director because I’m not much of a bloke. There are other directors who would do a better job of doing violence. I like to mix comedy and drama and “Cold Feet,” “Saving Grace,” and “Calendar Girls” all have that in common. I like making people laugh and cry. I’m a bit of a softie at heart and get a bit sentimental, but I get embarrassed about that so I like to puncture it with a joke. Romantic comedy is a genre where you can do both.

“The fact that this film is inspired by a true story brings its own challenges and pressures,” Cole continues. “It’s always important not to have a patronizing attitude towards your characters, because the audience can sniff that out a mile off. Because it’s a real story, we all wanted to remain true to the spirit of that story but we also wanted to make a good film, so we knew we had to take some liberties.”

Unfamiliar with the world of the Women’s Institute, Cole says he was unsurprised by what he found when he visited the ladies of Rylstone. “They turned out to be exactly as I had expected,” he says. “They were funny and bright and not at all conservative and dull. These women are in their mid-late 50s, so they were teenagers in the 60s. In the real story, there was very little opposition to what they did, but drama is about conflict, so we had to create some paper tigers – like with the board members at the WI conference in London whose approval they need to go ahead who, at first appear horrified by the idea but then come round. The characters of Chris and Annie were inspired by Tricia and Angela and they were always the naughty ones giggling at the back of the class, so I wanted to reflect that. One thing that did surprise me, however, was just how competitive that world is: the WI women really take the festivals seriously and they really care about winning the prizes.”

Cole was keen to ensure the film wasn’t just a knockabout comedy. “Perhaps in a different time, the film would have charted the struggle to get the calendar done and would have left the women on a high. I wanted to take it further because when I met the real women it was clear that – although they were all very happy that they’d done this very important thing – it wasn’t without its tears and I felt that was an interesting part of the story. I wanted to show that they flew quite close to the sun and burnt their wings. I’m glad that in the third act we addressed the idea of celebrity as a monster that gets out of control.”

Meanwhile, the filmmakers brought on board Tim Firth, the writer of such acclaimed television dramas as “Preston Front” and “Neville’s Island,” to rework Towhidi’s screenplay. “Juliet had created a beautiful and lyrical world for the film,” Mackie says, “as well as a cast of characters that were fully-rounded and completely authentic, but everyone felt that the screenplay needed some additional comic input and a northern voice, which we knew that Tim could provide.”

“I was very hesitant at first,” Firth admits. “I’d never worked on any pre-existing material before, and was unsure whether I could or wanted to do it. I had, however, bought the calendar the year it came out and as it turned out had met one of the Calendar Girls in the process without realizing it. My mum was in the WI and so was my Gran. Also, the girls came from the village where I’d spent every summer holiday of my childhood. And I had paintings in my house from the gallery of the guy who took the calendar photos, so everything just seemed to be pointing me in the direction of this film.”

One of his biggest challenges was negotiating the fine-line between the humor in the story and the raw, tragic drama of John’s death. “This is not a documentary,” Firth insists. “My attitude towards the true story was to know it happened and then forget about it. I didn’t meet the actual women until after I’d finished. For me it was very important to detach the film from its source and not get personally involved with the real characters in ways that might, frankly, impede me being critical if necessary. I identified the core of the story being about the achievement of celebrity through the most tragic of ends. This darker gene of the story and the comedy, which punctures any mawkishness, is an in-built antidote to sentimentality, which I’m not interested in. Fighting sentimentality in times of crisis is what I find genuinely moving.”

Director Cole concurs: “It would have been easy to focus on that side of the story – on a man dying of leukemia. I was keen to see the aftermath of that, so I worked very hard with Tim Firth on trying to make what could have been a chocolate box of sentiment into a film that had some edge. I encouraged everyone to think of it as a big film. That influenced everything, from the script, to the cast to the design.”

Casting The Film

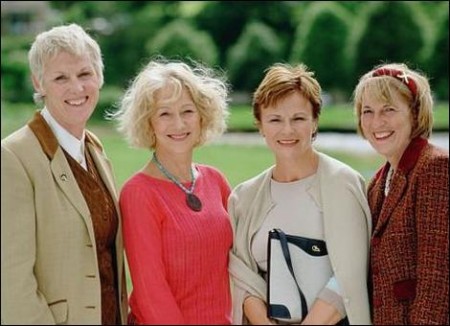

“When it came to casting, we wanted a couple of real movie stars,” producer Nick Barton says. Sometimes what you want is what you get. Among the first actresses to be sent the screenplay were Helen Mirren and Julie Walters, for the roles of Chris and Annie respectively. The Academy Award-nominated stars needed little persuading to sign up.

Says Mirren, “All great films have a combination of humor and seriousness and this screenplay managed that balance beautifully. I was immediately aware of how sensitive Tim Firth and Nigel Cole were to the delicacy of the subject matter. I loved the character of Chris and after meeting Tricia, I realized that Tim had certainly tapped into her dynamism and energy. Chris is the kind of person who would jump into the wrong end of a swimming pool. She jumps before she thinks, she’s spontaneous and gets overexcited about things that mean a lot to her. But that spirit gives her the courage, commitment and passion about what she does.”

For Mirren, working on the film brought rich rewards. “I’ve never worked on an ensemble film like this. A film about a group of women in middle age is a very rare beast and it’s been fantastic working with a group of such experienced and talented women. And such a group of actresses could have proved intimidating for a director. But Nigel handled us with exactly the right mix of charm and humor. I called him `Our Fearless Leader’.”

For Julie Walters, the part of Annie posed an unusual problem. “When I first read the script, I thought `Who is Annie?’ because Chris is so much larger than life that Annie disappears into the background. I was very keen to meet Angela Baker on whom Annie is based, not to do an impersonation of her, but to witness her relationship with Tricia, who is the model for Chris. I met all the women together and they are all very funny and witty. At first, I thought Angela was very shy, but first impressions are misleading. She’s not shy; she’s actually a strong, clear person. Then I realised what made up Chris and Annie: Annie sits back and watches whereas Chris barges in almost without thinking. And Annie loves that because it’s the opposite of her.

“With a film like this, which is inspired by actual events and where the characters are inspired by real people,” says Walters, “you have a much greater responsibility, so we’ve had to be extra sensitive. But Angela was very open and talks about what happened with great candour. And that has made it easier for me to get to grips with the character of Annie. It’s been a great relief for me to play her because I normally play the one who rushes in and never stops talking. It’s been the most relaxed film I’ve ever done!”

The decision to cast against type came from director Nigel Cole. “Probably the best call I made was offering Helen Mirren and Julie Walters the roles of Chris and Annie in that order,” he says. “Helen usually plays the quiet, sad one – “Gosford Park” and “Last Orders” were low energy, understated roles and in “Prime Suspect” she’s quite dour. Julie usually plays the loud, active one – look at “Personal Services” and “Billy Elliot.” I knew that Helen’s vulnerability would soften Chris, while Julie’s wicked sense of humor would liven up Annie.”

With Mirren and Walters committed to the film, Cole and his producers succeeded in attracting some of Britain’s best actresses for the remaining women – Penelope Wilton, Celia Imrie, Annette Crosbie and Linda Bassett.

Penelope Wilton took on the role of Ruth, whose story is completely fictional. It afforded Wilton much artistic license in bringing the character to life. “Ruth is the most timid of the group and is married to a rather charismatic carpet salesman whom she doesn’t know is two-timing her,” says the actress. “There is a sad element to Ruth’s story, but the crux of the whole film is about the friendship between women and how they look after one another and that’s very much the case with Ruth. She overcomes the shock and humiliation of finding out her husband has been having an affair thanks to the support of her friends. And she blossoms, thanks to that friendship. So it’s a very uplifting story.”

For Celia Imrie, who plays the most wellheeled of the women (coincidentally, also named Celia), one of the most important decisions was meeting the real women in Rylstone. “I’m not from Yorkshire, so I was very keen to see what kind of a community they come from and to meet the women as a group. It was very important to see what kind of relationships the women have with each other, what kind of lives they lead, what kind of houses they live in. The setting of the film is such an integral part and it was absolutely crucial to know how the village worked. I was also very glad that the film started the shoot on location in Yorkshire.

“After a visit to a nearby golf club and a chat with some of members’ wives, I got a sense that there seemed to be a hint of snobbery about the Women’s Institute from them. It was almost as though the clubs that mattered were the golf and Rotary clubs. So I thought that Celia, my character, used the WI as a way of escaping from her life as the respectable wife of a golf club member. The WI is about being with other women, and taking part in the calendar is a kind of liberation for her. And it also improves her marriage.”

Working with such a talented ensemble of women provided an unusual set of challenges for Nigel Cole. “It’s often difficult with a large number of characters,” he explains. “There were several scenes in this film in which Julie Walters was standing around with no lines, almost like an extra, which could be a little awkward. All the women lobbied to get more lines and those discussions were very stimulating but I had to say no, which was difficult because most of their ideas were great, but changing things would have thrown the balance of the film. It was hard work, if I’m honest. But having someone like Linda Bassett in a relatively small role really pays off because when they have a scene, you really notice it.”

Firth also enjoyed the whole film making experience, including collaborating with the director and the actors. “Nigel knew what he wanted the major beats of the story to be. This was great, because it allowed me the latitude to wander off into the fields either side of the story, knowing the path was still roughly leading to Oz. Or, in this case, Skipton. As a writer, it’s usually when you wander off the track that you take the greatest risks and find the greatest surprises. We spent a week working with the actors, largely answering questions, building back-stories, and addressing any little bumps that came to light during the read-through. As soon as the filming starts the writer falls back to earth in a ring of flame. The only day I went on set was to take one of my children and my Mum to see the fete scene in which I’d named the overall WI prize after my Gran. She was the reason my mother started going to the WI and so it was a real day of celebration, touched with the sadness of knowing that the person who started it all, and who would have loved it so much, was not around to see it. This struck me as being similar to how the calendar itself must have felt for the girls.”

The real calendar girls also had a chance to participate in the film. “We thought we’d be lucky if we got a pass to go on set for the odd day,” says Tricia Stewart. “We weren’t expecting anything more. So when we met Helen Mirren, Julie Walters and the rest of the cast it was completely marvellous.” It didn’t stop there, however. Stewart, Baker and some of their calendar co-conspirators also have walk-on cameos as the rival WI group, which gets beaten into second place by Chris’s victoria sponge in the cake-making competition.

The Look of the Film

Nigel Cole’s decision to cast the film with “real movie stars” was designed, he says, to elevate the film beyond the “small British film” pigeonhole. That ambition also informed the design and look of the film. For Cole’s collaborators, production designer Martin Childs and director of photography Ashley Rowe, the change of location from the natural beauty of the Yorkshire Dales to the manufactured glamour of Los Angeles allowed them to realize that ambition.

“In my very first meeting with Nigel,” says Childs, “we talked about how the calendar changes the way the two women, Annie and Chris, see one another, how it reveals things about them, and how certain aspects of themselves are brought to the fore by the process and the result of making the calendar.” Childs, who won a Best Production Design Academy Award in 1999 for his work on “Shakespeare in Love,” says, “It’s all there in the dialogue and gestures but, in addition to that, going to America was an opportunity to alter quite drastically the look of the film. Annie’s not just a fish out of water, she’s someone who’s beginning at last to face her grief; Chris, on the other hand (as ever) takes control, but here in America there are things she can’t control.

“First impressions of Los Angeles are that, yes, it has glamour, but it also has buildings that look and feel rather temporary, almost skin deep,” Childs continues. “Yorkshire, by contrast, looks like somewhere that’s been there forever and will stay there forever. We spent a lot of time in the early days driving around Yorkshire talking about the look of the film, and the emotional truth of the story and how you can get closer to that through the way people live, the houses they live in and the landscape.

“We deliberately avoided the clichés by making it look as if you can’t live there without having to work for a living. People have bills to pay, bikes to mend, they bunk off school, they fall out and they get cancer – just like anywhere else. It’s a working place and it just happens to be one of the most beautiful places on earth.”

After an extensive search throughout the Yorkshire Dales, Childs and his team chose Kettlewell to stand in for the film’s fictional village of Knapely, in part because although very characteristic of the region, it is not “the prettiest village in the Dales”. Four other villages in the area, including Skipton and Linton, were also used during the film’s nineand- a-half week shoot.

Childs’s proudest achievement on the film was the sets he designed and had built at Shepperton Studios. For the village hall, for example, Childs and his team “had a lot of fun with the details – years and years of paint upon paint. We installed old radiators with portable gas heaters in front of them to show they no longer work, balloons and tinsel left over from a Christmas party, old conduit, switch boxes that stopped working decades ago, Cora’s mad old art deco piano.”

Chris’s house was another favorite. “Chris and Rod are not only a messy couple with a teenage son, their house looks like they’ve just had the builders in,” says Childs. “The builders, though, had left without finishing or perhaps it was too messy even for them. Or maybe Chris and Rod were doing it themselves and just got distracted – another of Chris’s ideas that didn’t get finished. The builder subplot was done for logistical reasons too. When you’re up against a shooting schedule it’s a help if you have a big set, but Chris and Rod would never have been able to afford a big house, so we built a set that looked as if they’d knocked walls down and when the time came to shoot, not a minute was wasted pulling the set apart to make room for the camera crew and then putting walls back together again afterwards. That was a nice set to do, unfinished but deliberately so – it takes a skilled painter to make a wall look deliberately unpainted.”

For award-winning cinematographer Ashley Rowe, the vagaries of the weather conspired to create less than ideal shooting conditions. Rather predictably, the sun refused to shine in Yorkshire, but Rowe made the most of what little sun there was, to create a film with a summery feel. Just as Martin Childs had done with the design, so Rowe was keen to give the Yorkshire and Los Angeles locations a very different look.

“We used stockings over the lenses for all the English scenes to give it a softer, gentler tone,” explains the cinematographer. “We had to buy up the entire stock of tights from a shop in Wales because theirs were the only ones we could find which didn’t have a lycra mix in the nylon – lycra glitters in the light in a way that you can’t disguise.”

For the scenes in America, Rowe used a naked lens and, thanks to the bright Los Angeles sun, the film takes on a harder, cleaner edge with more shadow contrast and a fiercer tone. “Hollywood has a glamorous image but the reality never lives up to the myth,” says Rowe.

Shooting the Calendar

“It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” says Nigel Cole, of filming the calendar scenes. “Many of the actresses have never taken off their clothes on screen or in public. Many are considerably older than actresses who are prepared to take off their clothes on film, and we couldn’t and didn’t want to use body doubles. We did it mid-shoot because that gave us time to get to know each other and avoided having it looming over us throughout the whole shoot.”

The original calendar was, says the director, the biggest help in giving both the cast and the crew inspiration for what they had to achieve and how the end result had to look. Cinematographer Ashley Rowe consulted with photographer Terry Logan on how he had lit the scenes. “Terry used just a 1000 watt lamp and the look was very natural. We had to use more light for the filming, but we just boosted the natural light sources and really tried to keep it very simple and unfussy. The stockings over the lens gave more softness and helped even out skin tones because we were very keen for the women to look as beautiful as possible. I’ve done nude scenes before, but this was different, partly because of the age of the actresses but also because there would be a permanent reminder of the scene for the calendar. But these women are professionals with years of experience and they know how to look their best.”

Once the filming was over, stills photographer Jaap Buitendijk stepped in to take the shot to use as the final calendar picture. Although not exact replicas of the original photographs, many of the film’s stills are very similar. Post-production provided some interesting challenges for Buitendijk: “I had to digitally alter some of the photos so as not to breach the guidelines which Nigel Cole and the producers had set. For example, on Celia Imrie’s photo, the strategically-placed currant buns had to be enlarged to preserve her modesty properly.”

For the actresses themselves, it was an experience both intimidating and liberating. Says Julie Walters, “If Angela, Tricia and the other women could do it, how could we not do it? They were the brave ones, the pioneers, not us. And being part of a group made a big difference. By the time we got round to doing the group photo, we were all quite blasé about it!”

Annette Crosbie agrees: “We were apprehensive, partly because we had to take our clothes off not in front of just one man, but in front of a whole crew. Strangely, during the taking of the group photo, a man whom I’d never seen before kept appearing behind me. It turned out he was the man in charge of the gas fire. There must have been something seriously wrong with the fire because he came back three times to look at it!”

“One of the characters in the film says `You can’t see anything in the photos, but I expect there’ll be considerably more on display in the room!’,” says Cole. “That’s what concerned them. But the actresses had come up with a pact that they would all go naked if needed or not, to support each other. Some could have been wearing a bikini but they didn’t because of that group solidarity.”

Temperamental weather, digital tampering with currant buns, recreating the Jay Leno show in Los Angeles and of course the nude scenes all made the filming experience a tough but rewarding challenge for the whole team. “What surprised people about the script was that it’s not just about a group of women who do something extraordinary,” says Suzanne Mackie. “It’s about what might happen when they do that extraordinary thing. The third act is about the seduction of fame, how fame is mad and crazy and how these women pull each other back to reality.”

Production notes provided by Touchstone Pictures.

Calendar Girls

Directed by: Nigel Cole

Starring: Helen Mirren, Julie Walters, John Alderton, Linda Bassett, Annette Crosbie, Philip Glenister, Ciaran Hinds, Celia Imrie

Screenplay by: Juliette Towhidi

Production Design by: Martin Childs

Film Editing by: Michael Parker

Music by: Patrick Doyle

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for nudity, language, drug-related material.

Studio: Touchstone Pictures

Release Date: December 19, 2003