Among the various regions of the new world probably none carries more continued interest than that surrounding the Caribbean Sea. Off its northern border lies the first land seen by Columbus on his voyage of discovery, and within it is all he ever saw of the new world. In little more than a generation following his death occurred the spectacular spread of Spanish exploration and colonization which brought to Europeans a superficial knowledge of all of the Caribbean region and made it the starting point for expeditions which reached farther north than the site of St. Louis, Missouri, and farther south than that of Santiago, Chile.

In this same short period gold and silver began to find their way back by the Caribbean from Mexico and Peru and to make themselves a doubtful blessing in the mother country, a great stimulus to the commerce of more industrially developed nations, and a potent influence in turning attention from possible development of the Caribbean region itself to the farther territories which offered quicker returns to the adventurous.

Through the waters crossed by the first discoverers soon sailed the Spanish treasure fleets convoyed by warships to protect them from capture by the forces of the countries of northern Europe. On them came to be fought out the long struggle by which these latter sought to break down the Spanish trade monopoly and to secure footholds in the islands and on the coasts for colonies of their own.

For a hundred years Spain had a free hand in the Caribbean. Expeditions by her enemies made scattered attacks on silver fleets, but a century of American history closed without the establishment in the region of a single colony under other than Spanish authority. The following century, 1600 to 1700, brought still greater efforts by three north European nations—the English, the French, and the Dutch—to share in the American trade and to establish colonies in the lands lying across the gateway to the more prized Spanish possessions.

In point of time the English were the first rivals to attempt to occupy lands in the Spanish main. Here was, with the exception of Newfoundland, their first center of economic interest in the new world, and in time they not only took more extensive territories from the nominal original possessor, but to a large degree became the heirs of the other north European claimants.

Outposts for preying on Spanish commerce, bases for contraband trade, and lands on which plantations for tropical agriculture could be developed were the prizes sought. These, as the French and Dutch were soon finding in the same period, were easiest to secure and hold in the islands, especially the undefended smaller islands, and on the Guiana coast, regions in which Spain took little interest because of their lack of the precious metals—gold and silver.

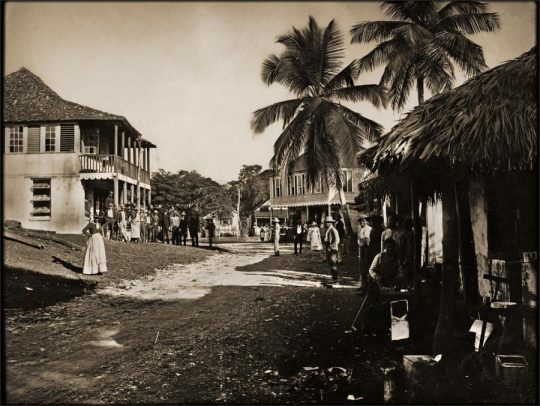

Even before the end of the fifteen hundreds, Sir Walter Raleigh had twice led expeditions against Guiana, the first serious attempt by northern Europeans to break down Spanish control in South America. In 1605 the English took possession of Barbados and in the years following seized others of the smaller islands. English colonial activity in the Caribbean was thus contemporaneous with the founding of the first colonies in New England. The middle of the century had hardly passed when Jamaica fell into English hands ( 1655). Its capture was, up to that time, the greatest break in the Spanish control of the American tropics.

In the sixteen hundreds France also set up colonial establishments in the Caribbean. They included claims on the Guiana coast and in a dozen of the Antilles from Granada, on the south, to Santo Domingo, on the northwest. These were settlements of varying character. Some were started by unrecognized outcasts like the buccaneers on Tortuga off the northwest coast of what is now Haiti; others were efforts with more direct support of the government intended to exploit the raising of tobacco and sugar, tropical agricultural products which would find a ready sale on the other side of the Atlantic.

The Dutch, likewise having won their independence from Spain, succeeded in establishing control over a portion of the new American territories. The first efforts in Guiana were almost contemporaneous with the settlements there by France. By the middle of the century their possessions had spread into the lesser Antilles and they had seized the small but strategic group of islands of which Curaçao is the most important. These, like the French colonies, were to exploit tropical agriculture. They were to be outposts for the slave trade and bases for attacking Spanish commerce. 1627 saw the Dutch capture of the silver fleet on its way eastward from New Spain, the greatest of their exploits against the former mother country and an incentive for future similar attacks.

Until 1670, Spain refused to recognize that any of these holdings established by other nations gave them legal title. She punished the invasions when she could, but by the end of the century it was evident that her pretense to exclusive control was becoming more and more a fiction. The northern powers held mainland colonies in Guiana, and they had taken practically all of the smaller Antilles. The English held Jamaica and the Bahamas. French settlements were firmly established in Tortuga and Santo Domingo and at the close of the century, in 1697, Spain was forced to recognize the French claim to the western part of the latter island by the treaty of Ryswick.

Even on the isthmian coasts Spain could no longer make her control unquestioned. Henry Morgan and his buccaneers had landed there in 1671 and captured the treasure which was being held at Puerto Bello for shipment to Seville. 1 English traders and logwood cutters had established themselves in Central America. An attempt had been made, unsuccessful it is true, to establish an English-Scotch colony at Darien.

The long established monopoly of trade and territory had broken down. The “foreigners” were already in control of the islands fringing the eastern Caribbean. They already held one of its larger islands and part of another. Smuggling trade with the colonies was already prosperous for the north Europeans and was becoming more and more general.

The period between 1700 and 1800 was one in which the superficial position of Spain in the Caribbean showed but little change. Four general European wars occurred in the first two-thirds of the century. They were conflicts which on the whole worked to the advantage of England. Fighting occurred in the Caribbean as on other American frontiers, but the Spanish losses of territory there were not of great extent. English claims were strengthened on the Nicaraguan coast and in the region which later became British Honduras.

An English fleet with colonial troops from New England captured Havana in August, 1762, but surrendered it again in July of the following year to a new Spanish governor. Judged only from the maps Spain seemed almost as strong in the Caribbean at the end of the century as at its beginning. But the maps reflected only political control. In naval power Spain had steadily lost ground and economically her rôle in trade had become less and less significant. Mastery of the sea had, indeed, long been slipping into other hands. The eighteenth century saw no check in the decline. Efforts were made to strengthen the navy both by increasing the number of vessels and by improving their designs, but the sea forces were never put back into a position to give real protection to the colonies against foreign attack or even to defend the interests of Spanish commerce.

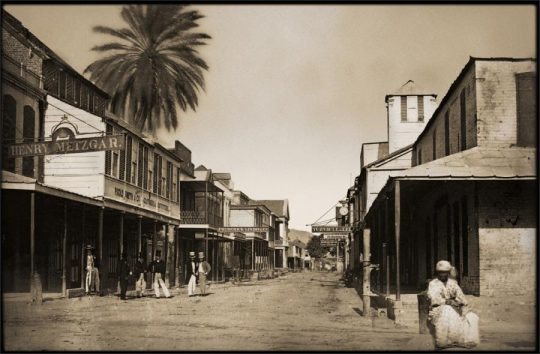

As early as 1713, the English forced acceptance of the famous Asiento by which the right to send a single vessel in the Puerto Bello trade was granted. The privilege was soon abused, for the merchandise to be sold from the ship was steadily replenished by cargoes brought by other craft sailing out of Jamaica. The Dutch soon followed the example of the English, using Curaçao as an entrepôt for goods intended for the Spanish colonies as the English had learned to use Jamaica. They soon dominated the trade of Caracas.

As a result of the agreements which Spain had found it necessary to grant and the abuses in commerce which developed both in connection with them and independent of their terms, far the greater part of the trade to the Americas fell into the hands of north Europeans. By 1740, the English alone were said to have as large a share as the Spaniards themselves. “In time every manufacturing nation of Europe, and even the North American colonists, had a part in the Spanish American trade.” Just after the end of the century over 19 per cent of all the exports of the recently established United States of America went to the Spanish West Indies, not counting what reached there indirectly by way of other European colonies in which another 39 per cent of the total found its market.

In the last half of the century, Spain liberalized her commercial policy in an attempt to improve her position in the trade of her own colonies. After 1748, merchant vessels were no longer required to sail only when accompanied by naval convoys. In the years following the reësblishment of Spanish control in Havana the restrictions were further modified, but though trade with the colonies increased, the number of Spanish vessels sailing to the western Atlantic continued low. Often they totaled not more than thirty a year, while the number of ships sharing even in the direct trade of Spain with the colonies reached, in some years, over three hundred.

Thus, though nominal Spanish sovereignty at the close of the seventeen hundreds extended over almost as great an extent of Caribbean territory as at their beginning, the advantages of possession had largely passed to others. Smuggling was profitable and respectable. Illegal trade for many years was of greater value than that carried on under the laws, and legal trade was passing out of Spanish control. Both the foreigners and the colonists profited by the new developments which helped, unfortunately for Spain, to bring about conditions which would shortly break down even the nominal political control which she had been able to maintain.

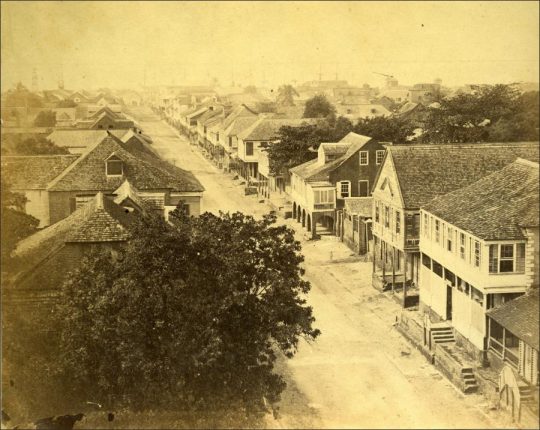

The nineteenth century in the Caribbean was marked by one disaster after another for the European colonial powers. In its opening years, France lost its highly valued sugar colony, Haiti. The end of the first decade brought revolutionary activity against Spain on the mainland, which, before the first quarter of the century came to an end, left her with effective control over only Cuba and Porto Rico, though long after independence was won she continued to refuse to admit the facts and recognize the independence of the new republics. The closing years of the century saw the last remnants of the great American colonial empire of Spain pass out of her possession. Only the British and the Dutch had at the end of the century holdings comparable in extent to those claimed at its beginning.

The Caribbean had come more and more under the control of the local populations. Haiti had proclaimed independence in November, 1803. Later the mainland colonies and the Dominican Republic followed the example. In 1899, steps were being taken to add Cuba to the list of republics and the United States, a new Caribbean power, had come into control of Porto Rico.

From a larger point of view the United States, which from this time on was to play an increasing rôle in its history, had long been a power in the Caribbean. Its interest in the independence of the Latin-American republics had been continuous from the time of their establishment. Possible European encroachments on their territories had at various periods caused anxiety to its statesmen. On a number of occasions it had sought bases in the region to strengthen the position of its navy. Isthmian questions had often claimed its attention, and Cuba, both for economic and strategic reasons, had played an almost continuous part in its foreign policy. But up almost to the close of the century no Caribbean territory had come under the American flag.

From an economic point of view the nineteenth century was on the whole disappointing. In the new republics the old restrictive policies which had held back their development vanished, and they were free to shape their own destinies. The more sanguine of the local leaders and many sympathizers in other countries looked forward to rapid advance in material development and the establishment of stable political conditions. Neither came.

Local capital was unable to undertake extensive exploitation of resources, and the markets for such tropical products as were produced, taken as a whole, did not expand rapidly or yield high profits. Foreign capital did not flow readily into countries in which the personalism characteristic of local politics destroyed the possibility of working under stable conditions.

Disturbances of the public peace discouraged immigration and enterprise and were a drag on social and economic advance. Internal division proved almost as great a handicap to progress as had been the short-sighted policy of Spain.

In the colonial areas also the economic outlook was not bright. The abolition of slavery and the consequent hard times in the sugar industry threw the British colonies into a long decline. The French colonies which were left after the Haitian revolt had an uneventful and, in even the best periods, only a mildly prosperous history. The Dutch possessions for many years were of doubtful value to the home country which found it necessary to contribute grants in aid to the local treasury.