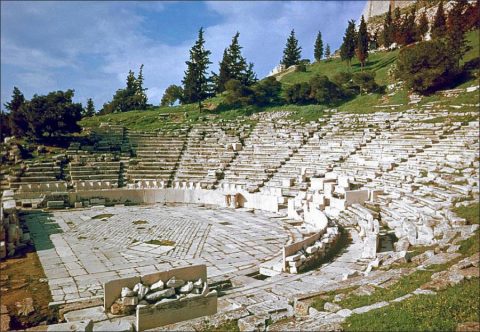

The Dionysiac Theatre is the sunniest spot in Athens. The tourists know it and bring their teabaskets. The lizards know it and steal out to bask on marble chairs dedicated to priests and magistrates. The Athenian audiences of classical times must also have known it as they sat there the whole of a spring day with the sun in their eyes and the rock behind them glowing like a furnace.

The existing remains of the Theatre of Dionysos are a complex of many periods and the fundamental questions whether there was a raised stage before the time of the Hellenistic theatre and whether the stage buildings in the classical period were of a permanent nature have not yet been settled to everyone’s satisfaction.

It is generally agreed that the orchestra with its central altar of Dionysos was originally occupied by both chorus and actors. There is also fairly general agreement that no stone auditorium existed before the Lykourgan theatre in the second half of the fourth century B.C.

The actual remains on the site may be divided into four periods: 1. Pre-Lykourgan; 2. Lykourgan; 3. Hellenistic; 4. Roman. The Lykourgan Theatre was built in consequence of a decree of the Boulé in 342 B.C. and completed before the death of Lykourgos in 326 B.C. This leaves a long period of at least a century and a half for the pre-Lykourgan Theatre.

The oldest remains are six blocks (SM 1) of a curved polygonal wall of limestone, generally believed to be sixth-century, some 100 m. eastnortheast of the Old Temple of Dionysos, which were identified by Dörpfeld as part of the original orchestra. By plotting an imaginary circle on the evidence of the stones he met a fragment of wall on its west side and a cutting (A) in the rock on the east side, north of the six blocks, which he thought were part of the circumference.

Many later authorities have rejected the evidence of either A or J 3 or both but nearly all agree that SM 1 supported a curved terrace which formed the boundary of the orchestra itself or had an orchestra of smaller circumference placed upon it. A fragment of polygonal masonry (SM 3 ) similar to the six stones, which is north of the west end of the Old Temple of Dionysos may have sustained a road or path rising from the level of the Temple to that of the orchestra.

Before the end of the sixth century the improvements in drama associated with Thespis must have taken place. He competed in the first state-organised performance of tragedy about 534 B.C. and is credited with having introduced an actor in addition to the leader of the chorus and the flute-player of the earlier drama. Temporary structures like tents (skenai) or booths doubtless served as dressing rooms, and it is uncertain whether any further provision was made for a background for the action.

Very early performances are known to have taken place in the “Orchestra” or dancing-place in the Agora. Its exact position has not been determined, but it probably was in the spot later occupied by the Odeion. The majority of the spectators evidently sat on wooden ikria or “bleachers” so insecure that their collapse on one occasion is recorded. The late lexicographers generally give this as the reason for the transfer of the performances at ca. 500 B.C. to the south slope of the Acropolis where there already was the Older Temple in the Precinct of Dionysos and where the natural slopes to the north, east and west of an orchestral circle could be occupied by spectators.

There seems little doubt about the move, but the date is less generally accepted, as many believe the Theatre of Dionysos was already in existence as early as the sixth century, even if some performances formerly held in the “Orchestra” in the Agora were transferred to the south slope after the catastrophe.

In the first half of the fifth century the number of actors was increased to three and some kind of a skené built of wood served as a background. It has been said that a wooden skené would not have been adequate for the action of the great tragedies of the fifth century, but no traces of a permanent stone skené earlier than the end of that century remain to be seen.

Another moot question is how much movable scenery may have been used. Panels or “pinakes” representing a wood or a cave could have been set up against the façade which under ordinary circumstances served as a palace or a house. We must also remember that many conventional uses known to us from vasepaintings and other sources, e.g. a tree for a wood, and a tendency to general simplification, would have been familiar to a Greek audience and far less disturbing than to a modern audience accustomed to spectacular realism or fantasy of mounting.

The introduction of more elaborate scenery with the use of perspective has been attributed by Vitruvius to Agatharchos who he says worked for Aischylos, while Aristotle says scene painting was introduced by Sophokles. Agatharchos may well have worked for either or both, for Sophokles first produced plays in 468 B.C., and the latest dramas of Aischylos were put on in 458 B.C. As long as the drama still remained a ritual ceremony for chorus and actors, there was no need of a raised stage for separate performers.

Before the end of the century, the wooden skené gave way to one of stone. The orchestra was moved slightly farther northward and was provided with a straight terrace-wall (H) ca. 62·18 m. long and 0·61 m. thick, built of a single row of breccia blocks laid lengthwise. A little west of its centre and presumably on the axis of the orchestral circle a solid rectangular projection (T) 7·92 m. long extends forward 2·74 m. It is built of breccia and had two rectangular holes, one 0·76 m. square, the other 1·21 m. by 0·77 m., in the floor which were found full of sherds, stones and earth. They may have held supports for the mechanical devices such as the crane that were employed.

The Dionysiac Theatre at Athens is neither the largest nor the most beautiful that the world has seen, but standing here we realize that this is the theatre par excellence. The original dancing-ground of the chorus, once perhaps a mere threshing-floor, has been traced partially outside the present orchestra. It formed a complete circle and therefore was better suited for dances than for the production of performances that must be viewed from one side only. Very early its south side must have been blocked by the skene or shed in which the actors dressed. In time this came to bear the scenery, and became the “scene”; the stage in front of it was known as the proskenion.

In Roman times the theatre seems to have been used for gladiatorial shows, and it was on this account that the upright slabs of marble were placed along the front of the seats to protect the spectators. To this period also belongs the covering of the gutter which runs around the orchestra and which originally carried off the rainwater for the whole building.

Visits: 253