One of the most charming features of Attica is the number of Byzantine churches appearing in odd unexpected places. At the end of a fashionable street, in the middle of a modern square, next door to a railway-station, under the shadow of the Acropolis Hill, in any place and at any time one may come upon one of these tiny golden buildings (a harmony of soft colours and dark tiled domes), its foundations sunk some feet beneath the level of the modern road. It is the same in the country districts. A fold in the barren hill-side discloses the site of some rich old monastery with its vaulted church: sometimes even without any monastery on an open moor or windy hill-top there stands a deserted church, its frescoes green with mould.

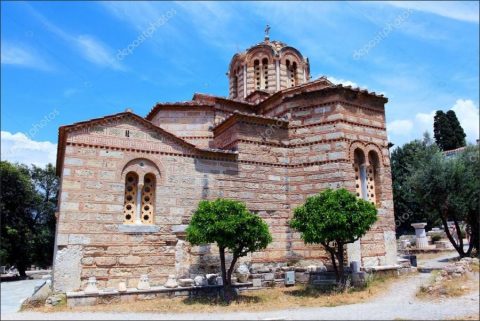

The churches of Attica fall naturally into two distinct groups: the larger ones which are more or less quadrilateral, belong to the basilica type. The smaller and more numerous churches, built in the shape of a cross, are known as the cruciform type. In these the nave, chancel, and transepts are higher than the other parts of the building, and give the appearance of a Latin cross. Sometimes the length of the transepts north and south corresponds to the length of the church east and west, thus retaining the proportions of the greek cross. Each of these arms is usually finished by a tiled cupola, and over the centre of the church, where the arms meet, a large cupola is raised on a higher drum, giving it a marked predominance. The rectangular spaces between the arms and the body of the church are often filled in by vaults or apses. Such a church becomes a group of swelling curves which lead the eye upward to the central dome that rests on its slender drum.

In the basilica group the cross transepts are not indicated by difference in roof-level. The central space is surmounted by a single dome of rather wide proportions. This rests on a low drum that does not rise much above the level of the roof. The narthex, which was originally the porch for the reception of those not yet admitted to church-membership, is now an extension of the nave. The effect of these churches is less slender and graceful than those of the cruciform group. Their massive proportions make them suitable for more important buildings, such as the large monasteries of Daphni and Daou.

As regards ornament no two churches are alike. The same motives are found but their application is different in each case. The church at Daphni was the only one wealthy enough to cover its interior wall surface with mosaic designs, and nothing can compare with the rich haphazard collection of sculpture in the outside walls of the old Metropolis Church at Athens. Yet among the smaller churches each has its own piece of special decoration, fresco or carving or brickwork, just as each part of the church had its own particular fragment of dogma or sacred history assigned to it. The walls are generally made of yellow stone, ornamented with red bricks, and the domes are covered with dark tiles. The bricks were often placed so as to form the sacred initials of Christ’s name, as is seen in the Alpha and Omega frieze which runs round the Church of Saint Nicodemus.

In towns where there were large congregations of Christians the wide spaces of the basilica were retained in the interior, as, for instance, in the great Church of Saint Sophia at Constantinople. In Athens there was no need for vast interiors. All that the worshippers wanted was a compact building to act as a baptistery or as the gathering-place for a small congregation. The churches of Greece are usually distinguished by their small proportions and by their wealth of symbolism in design and ornament.

The monasteries of Attica lurk in adorable hidingplaces. Fertility and seclusion were the points to be looked for in choosing a site. A well-watered valley was the most desirable situation, provided it were well hidden from the sea. The holy Brothers lived in constant dread of pirates, and with good reason. The ruined monastery of Daou is only just within sight of the blue water, yet it fell a prey to a band of sea-robbers in the eighteenth century and has never been rebuilt. If piracy was rife even so late as the eighteenth century, it had been still worse throughout the so-called Dark Ages. The final isolation of Athens was due in no small measure to the fact that the rocky headlands of the Aegean were known as the haunt of corsairs.

Four monasteries, Daou, Mendeli, Assomatos, and Kaisariani, together with the city church of Nicodemus and the great monastery of Daphni, complete the list of the larger churches in and around Athens. The story of Daphni is so intimately connected with the fortunes of the Frankish Dukes of Athens that it is treated in the next chapter, and we pass on to the little cruciform churches which seem more typically Athenian than their larger neighbours.

Churches of the Cruciform Type

Most attractive of all the town churches in Athens is the small building that stands outside the garish new Cathedral, its foundations already several feet below the level of the modern pavement. This is the Metropolitan Church, so-called not because it was the original cathedral, but probably because it was the church attached to the home of the Bishop or Metropolitan. It has many names. Sometimes it is called the Catholicon, sometimes Saint Saviour (Hagios Elevtherios), sometimes Panagia Gorgoëpikoos. There are conflicting accounts of its origin.

Some claim that it has been built on the site of an ancient temple to Eleithyia, goddess of childbirth, whose name they say survives in the modern name Hagios Elevtherios, as her cult survives in the special devotion paid to the church by Athenian mothers. Another suggestion, not irreconcilable with the first, is that this church replaced an older Christian building that stood on the same spot, and that was perhaps destroyed by the Iconoclasts in the eighth century. This theory would offer a satisfactory way of accounting for the haphazard collection of sculpture, of which the church is composed. It certainly looks as though a heathen temple and an older Christian church had both provided materials for the odd patchwork of ornament, classical and Christian, sacred and profane, sometimes right side up and sometimes upside down, which has been built into the four outside walls of the church.

There are numerous small Byzantine churches scattered through Athens. They are already receiving the attention of scholars, and one looks forward to the day when there will be an exhaustive work on the subject. In the meantime they stand in the middle of the modern town, a puzzle and an allurement. On feast days they are dressed with myrtle and small blue flags, and the interior smells of incense and honey.

The honey scent seems to come from the candles, which are made of beeswax, a genuine native industry. In a sense the churches seem the special property of the Athenian bourgeoisie, for each one has a distinct place in the life of the citizens. At some of them cures are still wrought, as, for instance, in Saint John of the Column. Here an old church is built around a classical column. It goes through the middle of the church and sticks up through the roof like a chimney. In the inside it is hung with rags brought from the sick who wish to be healed.

The remains of Byzantine Athens hide away in unlikely corners. We find them when we cease to look for them. It is much the same with the story of their builders. We know desperately little of the history of those nine centuries during which the fate of Athens was absorbed in that of her greater neighbour–Constantinople. From the foundation of the Eastern capital of the Roman Empire in the fourth century to its overthrow by the crusaders in 1453, the fortunes of Athens were those of a provincial town on the outskirts of a harassed empire. She had her brief spells of glory, her small triumphs, her recurring misfortunes.

Then again she lapsed into obscurity, and for perhaps half a century her history has to be constructed from the mention of the town as a halting-place of an imperial traveller or from a runic inscription left by a northern invader. Owing to this meagreness of information these long centuries have been thrown together and called by the one comprehensive, noncommittal name–“The Byzantine Period.” Yet the single term is misleading. These years are not marked by any one salient characteristic. Athens was not on the downward grade throughout. There was a period of economic decay followed by a slow revival of prosperity. Society passed through a variety of changes. The provincial institutions of ancient Greece slowly moulded themselves to the form of Byzantine feudalism, as in a later age the Byzantine Archon and Kavallaris themselves in turn gave way to the Frankish Baron and Knight.

Speaking broadly, the period of decline in Greece lasted from the Emperor Constantine to Justinian, and from Justinian onwards there was a gradual increase of prosperity. As the power of Christianity increased Athens gradually lost her prestige. History inclines to depict her as the faded beauty who clings to the memory of her former triumphs. She still practises the heathen rites, still keeps open her schools, and wonders why the world no longer heeds the voice of her charming. In time she is forced to recognize that her old position is undermined. The new teaching which had drawn men’s hearts from the outward to the inward and had set symbolism for beauty was now united to the seat of world-power. The new hierarchy in heaven and earth left Athens and Olympos bare. What was the Parthenon bereft of the brooding spirit of the great image within? What was Parnassos without those dim presences among its clouds?

Visits: 191