The dates both of Sappho’s birth and of her death are unknown, but it is clear that she ‘flourished’ about 600 B. C. Her birthplace was Eresus in Lesbos, but her life was spent mostly at Mitylene in the same island, though she was for a time banished and sailed to Sicily. She was married and had a daughter; one of her brothers, Charaxus, became entangled with the courtesan Rhodopis in Egypt, and Sappho reproached him in a poem to which Herodotus refers and of which fragments have recently been found at Oxyrhynchus. The poet Alcaeus sought her love, but she seems to have rejected him; we possess a fragment of his address and another of her reply. At Mitylene Sappho had a school of girls to whom she taught music and poetry; in her extant work are frequent allusions to pupils and rivals.

Her writings originally filled nine books, but what now remains is in bulk pitiable. It is said that the poems were deliberately destroyed, through clerical influence, in the Byzantine age; the extant fragments escaped because they were quoted in prose writings. Two of these are of some length. The Ode to Aphrodite (twenty-eight lines) is preserved by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, the so-called Ode to Anactoria by the author of the treatise On the Sublime.

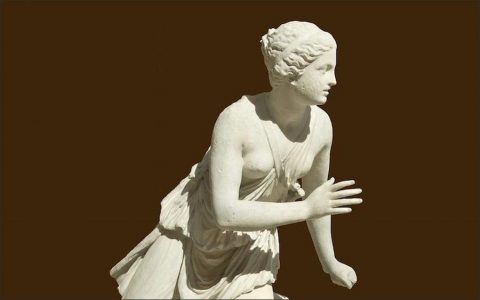

Sappho has been universally regarded as the greatest of all poetesses. The same qualities shine throughout her work, in single lines–quoted originally not for their excellence but to illustrate some point of dialect or metre–as in complete poems. Those qualities are beauty, vibrant life, a peerless faculty of directness–this even in the lighter, sometimes humorous, pieces.

But nearly all her extant writing is personal love-poetry, where the steady blaze of passion, the divine simplicity which is never naïve, but the outcome of superb genius wedded to immense spiritual force, have created flawless perfection. Others write (as we put it) about love; Sappho writes love itself. Keats and Propertius, splendid as they are, convey passion by elaborations, similes, allusions to story, moving through the mazes of sophisticated emotion. Sappho by miracle tells the fact itself, in her lovely Aeolic dialect and mostly in a simple metre invented by her and called by her name. Translation must evidently be a weak substitute, but a version which, refusing alien enrichment, retains a touch of her own simplicity and fire, may well be studied

God! What ecstatic joy to be

The man who sits before you, he

Into whose ears melodiously

Your tones descend,

Your lovely laughter, that dismays

The heart within me; when I raise

My eyes to you a moment, strays

My voice away.

My speech is shattered; through my limbs

Deep runs a liquid flame; all swims

Before my eyes; a torrent brims

Loud in my ears.

Sweat streaming falls; a tremor shakes

My body wholly; blood forsakes

My pallid cheeks; life all but takes

His leave of me.

Visits: 314