Modern Athens

City of whiteness and brightness. A city of sun and wind, of mountain freshness, and dazzling, sun-dried air. This is how Athens strikes the traveller from northern lands. For the city that first greets him is the modern Athens with its broad, straight, shadeless streets, its blocks of high white houses geometrically arranged, and its open squares filled with orange-trees and date-palms. The old town that lies tucked away between Hermes Street and the Acropolis has to be discovered later.

Athens, the modern town, may lack romance, but instead she has her own gaiety and charm. The city is still in her first vigorous youth. She is still divided between contradictory aspirations. On the one hand she strives to renew the glories of ancient Hellas, while on the other she sees herself the Paris of the East, “le petit Paris,” as Athenians affectionately call her. Nor are these ideals eventually irreconcilable. Why should not Athens borrow the shady boulevards and gay squares of Paris, without sacrificing her Hellenic traditions? Though the reconciliation has not yet been attained, much has already been accomplished.

The Acropolis lifts its treasures above the reach of all modern improvements. A high standard of comfort and efficiency in the modern town will not render the traveller less able to appreciate the glory of the ruins. It is impossible for new Athens ever to have that flavour of miscellaneous antiquity which charms in Rome. Therefore, since she must remain modern, let her modernity be of the best.

The wealth of marble shows, too, in the many public buildings which patriotic Greeks have given to their town during the last generation: the University with its shining figures of Apollo and Athena; the Library with its outside staircase sweeping down in a unique and delightful curve; the Zappeion, a large exhibition building set in its own new public garden; and the long perspective of the marble Stadium showing white among the young plantations on Ardettus.

The creamy buildings, the gardens, the vistas of sea and hills–these are the features that give modern Athens her charm. And to these must be added the intoxicating air, the continual scent of orange-blossom and mimosa wafted from hidden groves, the gaiety of troops and bugles, not to speak of the blue and silver liveries on the royal carriages and the stir around the brilliant little court.

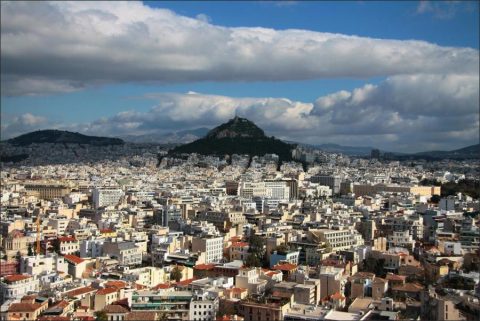

There are really two centres to the town. Constitution Square is the haunt of the foreigner. Here are the royal Palace, the smart hotels, the tourist agencies, the sellers of almond-blossom and violets, the islanders showing their webs of lace or baskets of sponges or eastern rugs held out over one arm. Concord Square at the lower end of the town is the centre for the natives. From it radiate all the main streets. Here are hotels, clean and roomy, with good Greek restaurants below; here are the banks and business houses. From the region around Concord Square a number of straight new streets run up the slopes at the base of Lycabettus. The beak-like rock of Lycabettus seemed to dominate the whole town. The Acropolis and even Hymettus seemed far away and insignificant by comparison. It was quite a shock to learn that instead of needing guides and a rope Lycabettus is a mere gardenhill and can be climbed before breakfast.

Athens is the capital of Greece, but it is also the market town for Attica. This fact is pleasantly emphasized by the groups of peasants who each morning converge upon the city from the surrounding country.

Alas! poor bird of passage, how much he gains and how much he loses! He gains a remoteness of spirit which the dwellers in Athens cannot always attain. The stranger can, if he wishes, ignore the social life around and feed on the memories of his classics until the shadows of his fancy become more real than the noisy phantoms of the modern town. His memory is not blurred by repeated impressions. His one first vision stays. Passers-by who have only a day or two in Athens are wont to be apologetic for their haste. They do not understand that they retain treasures of emotional sightseeing which the city-dwellers can but envy. Yet on the other hand, the traveller with three days in Athens, who comes begging for crumbs of beauty from Athena’s table, must be content with all she gives him, even though it be no more than two grey mornings on the Acropolis with a March wind blowing dust into his eyes and a crowd of guttural Teutons exploring the holy places.

Let him be reticent in his disillusion, for is there not, after all, some discourtesy in approaching beautiful places at unsuitable times? The real spirit of worship should wait for the goddess to reveal herself at the moment when her beauty is more apparent, her abasement most hidden. This is the instinct that lies behind the custom of visiting the Parthenon by moonlight. It is worth any effort to know the Acropolis at its happy hours, at sunrise and sunset, by moonlight and starlight.

To see sunrise from the Acropolis is to watch the chill purity of dawn shivered into fragments by the hundred golden lances which the sun sends before him over the grey shield of Hymettus. The columns of the Parthenon stand pallid, unmoved, and silent. Then in an instant the change comes. In the fraction of a second the marble is transformed from death to life. The golden glow flashes like a quick smile. The magical instant is over and the daylight world reasserts itself. Are not the swift revelations worth hours of noonday communings?

Moonlight has no special Athenian attributes. The wonder is concentrated on the silver glory and the great temples lose some of their individuality; these inky shadows and sharp silhouettes might belong to many another ruin in the moonlight. The silent, starlight hour before the moonrise reveals more of the spirit of the Parthenon. The stars move so peacefully below the black edge of the Acropolis. The whole world seems circling round the solid columns anchored up here in space. And in these dusky hours we get a chance of another sensation when Athena’s own owl flaps slowly out from under the temple’s shadow. But the time of all others for the revelation of what beauty means is the time of sunset in summer.

At the end of an exhausting day the Acropolis is almost deserted. The tourists have left the city and the Athenians who remain prefer more social haunts. Yet the air that greets one at the end of the climb is a special benediction of coolness. The town lies below parched and panting. Up here the breeze from the sea is blowing freshly, and if it is a lucky evening, as the sun nears the heights of Cithæron, the air begins to tingle and vibrate with colour.

Visits: 440