Mediaeval capitalism, precocious and adventurous as it was, was sporadic in incidence. Its progress was hampered by forms of wealth difficult to negotiate. Markets were small, and the spirit which dominated them was local and exclusive. Industry shared this localism of outlook; it was generally decentralized in organization, and its tools and techniques, however, serviceable in the hands of skilled craftsmen, could not meet the demands of an enlarged market. Travel, whether by land or sea, was beset by dangers; means of transport were inadequate. There was an insufficiency of good coin and a relative abundance of bad. Inelasticity of credit was the product of these difficulties.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries these conditions were yielding to change. Geographically early modern capitalism extended its radius, especially in the penetration of northern and eastern Europe, and in beginning the exploitation of other continents to which the age of discovery had opened seaways. In western Europe trade was slowly shifting from its ancient seats commanding the Mediterranean highway, to northern and western ports facing the North Sea or the Atlantic Ocean. Political consolidation in several European states opened new opportunities for profit-making to monied men in the financing of courts, administrative machinery, armaments, and war. This consolidation tended to widen and link home markets, and to stimulate competition for European and overseas trade. New supplies of the monetary metals provided an exchange medium sufficient to the dimensions of trade, and gave to capital a mobility not hitherto enjoyed. Communication between business centers was quickened, and striking advances in mining, industry, and transportation speeded the production and distribution of goods.

However controversial the economic results of the Reformation, it is indubitable that certain communities — Amsterdam among them as we shall see — profited by the dissemination of skills and techniques brought in by exiles fleeing religious persecution, war, or war taxation. And under a regime of discrimination such as that to which Huguenots were subjected in France, nonconformists in England, and Jews almost everywhere, the exclusion of the heterodox or the unbelievers from opportunities in other fields of eminence resulted in a striking channeling of their energies in business. In such circumstances the unity of the religious group was apt to assume business as well as spiritual and social validity, and from this solidarity useful commercial and financial connections sometimes developed.

For the most part the new wine was sedulously poured into old bottles, those being the only bottles at hand. The student of the period becomes used to being surprised, if the bull may be pardoned, at the mediaevalism of the façade behind which a modern economy was taking shape. Manor, gild, and fair might be in process of dessication as economic institutions, but in law, and in the minds and habits of men, they were apt to display astonishing powers of survival.

Burgher right, staple right, market right, local mint, and local toll persisted stubbornly in defiance of an expanding geography of trade. Even such hoary nuisances to the business world as strand law, droit d’aubaine, and sanctuary, made ghostly reappearances even in the late seventeenth century. The most modern features of the economic life of this period — the metropolitan entrepôt in which a large part of European trade was concentrated, the bourse or commodity exchange, and the joint-stock company by which large commercial and industrial enterprises were financed — were less novel by origin and intention than by involuntary adaptation to changing conditions.

The first and second were outgrowths of the fair and long bore traces of this origin. The third had antecedents in forms of cooperative enterprise common in the middle ages. Of the expansion of credit much will presently be said. Here it may suffice to note that notwithstanding the widening and multiplying use of bills of exchange and the rapid rise of banking in the seventeenth century, a great deal of trade ran on a cash basis. There was an extensive movement of coin and bullion, partly speculative, partly to settle balances in commodity trade between country and country, but also because sellers demanded to see the color of their monies.

For the greater part of the sixteenth century Antwerp “most renowned merchandizing City that ever was in the World,” had been both commodity market and financial center of northern Europe. When misfortune overwhelmed this city late in the century, the sceptre passed to Amsterdam, there to remain through the first half of the eighteenth century. In this period of Amsterdam’s supremacy we may see some of the transitions and some of the conservative prepossessions at which we have glanced. Her reign, like those of Venice and Antwerp before her, was the reign of a city — the last in which a veritable empire of trade and credit could be held by a city in her own right, unsustained by the forces of a modern unified state. In another respect Amsterdam’s heyday was final: the seventeenth was to be the last century in which the trade of Europe was in greater part still intra-European, and therefore susceptible of domination, as it had been dominated in the past, from a position commanding the crossroads of European — not world — travel.

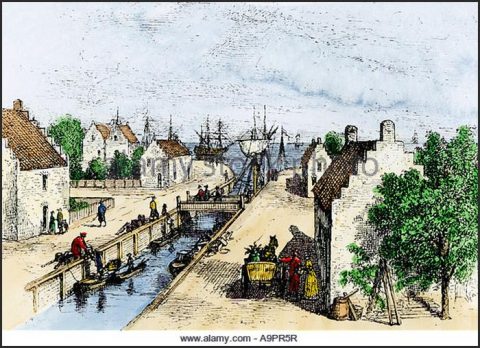

The succession of Amsterdam to Antwerp had not been determined by obvious advantages of site. The city was built on piles to prevent it from sinking into the marshy soil. The port lay far back from the sea, and was difficult of egress when the wind was easterly. Shallow waters made necessary the use of lighters for loading and unloading ships. Few European ports were in better case on this last point however, and difficulty of access and the aqueous site were compensated by defensibility against attacks whether by land or sea. Texel and Vlie were reasonably protected advance-ports for the assembling of Amsterdam’s fleets, and communications by river and canal with other towns of the Netherlands, and with adjoining regions of Germany and France, were unrivalled in this age.

And if any one doubt whether Amsterdam be situate as well and better than any other City of Holland for Traffick, and Ships let out to Freight, let him but please to consider in how few hours (when the wind is favourable) one may sail from Amsterdam to all the towns of Friesland, Overyssel, Guelderland and North-Holland, & vice-versa, seeing there is no alteration of Course or Tides needful: And in how short a time, and how cheap and easily one may travel from any of the Towns of South-Holland, or other adjacent Inland Citys to Amsterdam, every one knows.

Making the most of her advantages of position, Amsterdam had built up a thriving trade before the middle of the sixteenth century, and was renowned for the number and size of her ships. This early prosperity, founded on the fisheries and the Baltic trade in which Netherlanders had eclipsed their Hanseatic rivals, broadened to include a carrying and entrepôt trade between northern Europe, principally in grain, timber, pitch, tar, metals, hemp, flax, and fish, and western France, principally in wine and salt. Lodovico Guicciardini in 1561 wrote admiringly of the wealth of Amsterdam merchants, but it is possible that some of the capital which built and freighted ships, and bought up in a few days the cargoes of whole fleets laden with Eastland commodities, may have come from Antwerp; and the shipping of Amsterdam and of other ports in the northern provinces sought employment in the great market on the Scheldt which had little shipping of its own. In the middle years of the sixteenth century Amsterdam seems to have had little surplus capital in excess of the needs of her own trade and the ships that carried it.

Sir Thomas Gresham, who knew continental money markets well, thought of Amsterdam, if we may judge from his correspondence, only as a place in which to buy wainscoting. The city was known to be well-stocked with grain, lumber, and fish, but had yet to become a general mart like Antwerp or Hamburg where merchants might confidently expect to find all kinds of commodities in commercial quantities. When Guicciardini wrote, Amsterdam had no direct sea-borne trade with Mediterranean or with transoceanic lands. Her burgher class was prospering, but there was no group of conspicuously wealthy men in the ascendant. Amsterdam merchants, having no bourse in which to do business, met out of doors in good weather, and in a chapel in bad. The city had as yet no banks, only a licensed tafel van leening or ‘lombard,’ lending money on pawns at usurious rates. Exchange usages were borrowed from Antwerp, but hard cash was probably the rule in business transactions. Amsterdam’s industries, compared with those of Flemish cities, were undeveloped.

From this chrysalis of economic simplicity Amsterdam emerged — somewhat abruptly, as it seemed to contemporaries — in the quarter-century covering the last fifteen years of the sixteenth century and the first decade of the seventeenth, to enter upon a metropolitan and cosmopolitan career. Antwerp fell to the Duke of Parma in 1585. Her port was closed, and the noble cities of Flanders and Brabant were isolated and impoverished. Seville and Lisbon were officially barred to rebel Hollanders, and though the latter were willing to run great risks for the sake of great profits in trade to enemy ports, losses were sometimes catastrophic.

Trade with France was dislocated by the religious wars. In the face of these changes and dangers Dutch merchants sought direct access to Italy, Turkey, Guinea, the Americas, the Far East, and after the accession of the first Romanoff tsar captured first place in the trade of Russia despite the privileged position of the English Muscovy Company. This rapid commercial expansion was stimulated and in part enabled by an influx of thousands of refugees exiled from the ruined cities of the southern provinces, from Poland and Germany, Spain, Portugal, France, and England.

Several towns of Holland and Zeeland benefitted by this new wealth-making skill and energy, but it was Amsterdam that drew most active recruitment from it. In a country trampled and shattered by war, Amsterdam was reckoned impregnable. The hopeful state of commerce and shipping attracted business men from other lands. In an age when even enlightened communities suppressed religious nonconformity and discriminated against aliens, Amsterdam’s gates stood open to all religions and nationalities.

The status of poorter (citizen) could be acquired at a cost of f. 8 until 1622, when it was raised to f. 14. Though required for admission to gilds, and to certain occupations which included retail trade, its privileges seem not to have been consistently enforced. In admitting foreign craftsmen Amsterdam compromised with gild opposition, found housing for newcomers, and offered inducements to masters deemed capable of starting new industries or improving techniques in those already established.

In course of time regular shipping services connected Amsterdam with the chief trading towns in the United Provinces, with several cities in the southern Netherlands and northwestern Germany, and with Rouen and London. Postal services were extended to meet the needs of trade. Thus port and market were made accessible over a lengthened radius. The Vroedschap, governing council of the city, strove to better the condition of the currency and to provide security for capital. Special courts were set up to handle commercial, maritime, and insurance causes.

Foreigners observed Amsterdam’s rise to supremacy in world trade with surprise not unmixed with resentment. Suddenly, as it seemed, the city was there. The chamber of assurance was set up in 1598; the United East India Company was chartered in 1602; a new bourse was begun in 1608, and in 1616 the Vroedschap resolved to erect a special bourse for transactions in grain; the exchange bank was founded in 1609, and a lending bank in 1614. Revenue from customs more than doubled between 1589 and 1611.

Population soared; reckoned at about 30,000 in 1567, and not greatly in excess of that figure in 1585, it had mounted to 105,000 by 1622, to 115,000 by 1630, and may have passed 200,000 before the end of the third quarter of the century. To accommodate these numbers the town was repeatedly enlarged at great cost in piledriving and fortification, and in canal- and bridge-building. Visitors came from all parts of Europe to marvel at the wealth, beauty, and populousness of this queenly city. As early as 1600 the duc de Rohan declared that Amsterdam had no equal in Europe for wealth and beauty save Venice only. Adam Olearius, who had travelled in the Far East in the late thirties, heard men speak of Amsterdam “even in the Indies.”

The primacy of the city was threefold: as shipping center, as commodity market, and as market for capital, Amsterdam came to surpass all other European towns. It is difficult to say which aspect of her greatness was most substantial, or to dissociate one from dependence on the other two. Shipping was the city’s oldest productive asset of more than local consequence. In the mid-fifteenth century Philip the Good of Burgundy had referred to Amsterdam as “le notable port, la ville la plus marchande de tout notre pays al Hollande.”

In the sea war waged against the Hanseatic cities of the Baltic from 1438 to 1441, Amsterdam was said to have furnished more than twenty fighting ships, a number which exceeded those contributed by all the other cities of Holland and Zeeland combined. By the mid-sixteenth century a foreign visitor was already likening to a ‘forest’ the close-thronging masts and spars of the shipping in Amsterdam’s port — a simile which was to recur in many subsequent descriptions. An Englishman who came to the city in 1586 in the train of the Earl of Leicester, wrote: “There belongeth to this towne a thousand ships, the least of the number of a hundreth tonne, besydes numbers of other shipps and lesser vessalls.

They travill furth of most partes to yt, being furnished in a manner for all traydes.” Mindful of the easy roundness of figures uttered in the sixteenth — or the seventeenth — century, we may take this to mean that Amsterdam was frequented by an impressive number of impressively large ships. It was precisely in this period of the city’s swift rise to metropolitan stature that Dutch shipyards began turning out a carrier known as the flute (fluit), a cargo ship cheaply worked and of good sailing qualities. The success of the flute placed the carriage of a large part of European trade, particularly in bulky and heavy commodities, in Dutch hands, and the freights in Dutch pockets.

The type did not originate in Amsterdam, and we have no means of knowing whether she was a great builder of flutes, or merely supplied by a leap of her Norway trade much of the timber and plank for building them. Growth of shipbuilding and ship-freighting in Amsterdam is substantiated by the fact that in 1580-1604, 1,083 persons concerned with the building or the operation of ships were admitted to poorterschap. It is significant that a large majority of these — 677 out of the 745 whose previous places of residence were recorded — were not exiles from foreign countries but came from towns in the northern Netherlands, most of them from North Holland and Friesland.

Evidently such employments were being better rewarded in Amsterdam than in the smaller maritime towns and villages. A sawmill, invention of the late sixteenth century prompted by the demand for plank for houses and ships, was in operation in Amsterdam from the year 1598, and when the original owner’s twenty-year monopoly of mechanical sawing ran out in 1619, sawmills multiplied rapidly on the outskirts of the city. But in Zaandam they were more numerous still, and it may be that even in the early years of the seventeenth century Amsterdam shipwrightry was concentrating on turning out large and powerful types, leaving however unwillingly the construction of cargo-ships to the villages along the Zaan and other places where it could be done more cheaply.

Wherever built, the flutes flocked to earn their freights in the service of the metropolitan port. Pieter de la Court was to point out that a great commodity market, capable of buying up the cargoes of whole fleets, and of providing return cargoes as promptly, was an important factor in keeping down freight rates, and in attracting shipping both Dutch and foreign, “So that the English and Flemish merchants &c. do oft-times know no better way to transport their Goods to such Foreign Parts as they design, than to carry them first to Amsterdam, and from thence to other places.”

As a commodity market Amsterdam rounded out her position after the fall of Antwerp to that of general emporium. She purveyed everything, from objeis d’art which attracted foreign visitors to her shops, to fleets ready to fight. The commodities bought and sold on her bourse were staples of world trade; their range and assortment were standards to be consulted in lesser markets; and Amsterdam prices served as indices to commercial Europe. Price lists were printed weekly from 1585, and may have circulated even earlier. In 1613 the sworn brokers of the city were charged with compiling an official list to which anyone could subscribe for f. 4 a year. Recently searched out and studied by Dr. Nicolaes Wilhelmus Posthumus as the basis of his history of Netherlands prices, they have been found not only in collections in Holland and Zeeland, but in Antwerp, Brussels, Danzig, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Seville, Florence, Vienna, and Batavia.

Merchants who consigned wares to Amsterdam could usually count on quick sale, prompt payment, and broad choice of opportunities to invest the proceeds. If they decided to store their goods in expectation of better prices, they could borrow money on the security of their warehouse receipts. Or they could re-export, paying relatively small duties. Most goods, indeed, came into Amsterdam only to go out again. Expert knowledge of market conditions the world over, skill in appraisal and classification of merchandise, informed brokerage, commission, and wholesale services, credit, insurance, and exchange facilities — all these were to reach their highest development for the seventeenth century in Amsterdam.