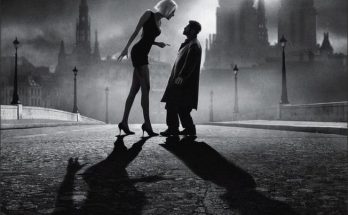

Christian Petzold’s new film Undine, which we can describe as one of the most important directors of contemporary German cinema, which blows our minds with its wonders such as Ghosts – Gespenster, Yella, Barbara, Secret in Your Face – Phoenix and Transit, had its world premiere at the 70th Berlin Film Festival, and Paula Beer at the festival. She brought the Best Actress Award and won the FIPRESCI Award.

Starring the two stars of Transit, Paula Beer and Franz Rogowski, the film brings the mythological nymph Undine to today’s Berlin. In addition to the love story of Undine, who appears as a historian in the film, and Christof, an industrial diver, Petzold also includes Berlin, which was destroyed and rebuilt many times, into his narrative with the ever-changing meaning of streets, squares and buildings. We met with Christian Petzold on the occasion of his new movie in Berlin in February and had a conversation about the movie.

How did you decide to make a contemporary film based on a mythological character like Undine from the ancient period but set in the present?

Christian Petzold: Years ago, when I became a father for the first time, I went back to myths and fairy tales. From the Brothers Grimm to Andersen and Greek myths, I reread many fables because I had to read them all to my children. Just like my dad used to read it to me when I was a kid. However, reading these books as an adult was, of course, a different experience.

I started seeing stories from a different perspective. I’ve rediscovered that just like Japanese anime, they have a structure that describes a magical world but also helps us explain what’s going on in the real world as we know it. For example, there is a fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm. This fairy tale is about a dying boy and his mother.

The distraught mother, whose child has died, continues to put food on the table where her son sits every evening. The child gets up from his grave every night and sits at the table with his mother. At the same time, he tells his mother to stop worrying so that she can sleep peacefully in the grave. Too terrifying for a fairy tale, this story is also full of advice on coping with grief and death. I can say that I started to think about fairy tales and myths again because I thought they were magical stories that we can explain our day and our world.

The film has a structure that considers love as a “death and life matter”. Is this just about the Undine myth you started out with?

Christian Petzold: I believe that many of the Greek myths and almost all fairy tales are basically love stories. I think these stories revolve around how people love each other and feed off the bond between them. I think that we can perceive the story from the perspective of love, whether it is Chaplin movies or an old fairy tale, and this feeling has not changed. Whether the story takes place in the past or is a contemporary story, we can understand it through this feeling. When it comes to love, it is impossible for the story not to reach an all-or-nothing point.

In parallel with the love story between Undine and Christof, you also include Undine’s love-hate relationship with Berlin. How did you decide to include Berlin in the film?

Christian Petzold: My personal love story for Berlin has a big part in it. I have lived here for nearly 40 years and this city is at the center of my life, but I must say that this love is no longer a love from the heart but a love controlled by logic. Because you have to live in this city for such a long time and try really hard to keep your love, especially today, when the city has become so ugly, people have become so unpleasant, life has become so difficult.

Besides, the weather isn’t very good either! That’s why you have to constantly find new reasons to love this city. Loving this place is not like loving the place where one was born, because most of the people in the city, including me, come from other cities, from other countries and are trying to make a life here. Undine also has such a relationship with Berlin. He is constantly explaining the city to himself and to others

In this way, he believes that people can stay… On the other hand, I can say that Berlin is unrecognizable in most of these works, despite being a city where many movies were shot. I can even say that what we learn about today’s USA by watching American western films set in old times is more than what we learn about Berlin in films set in Berlin.

In my opinion, Berlin is a city where the history of the city cannot be explored only linearly, but where the present and the past can be seen intertwined, only to be understood in this way. This is a place where a house destroyed during the war and a house built for investment in peacetime stand side by side, where the two mean different things. You should not approach Berlin with a reductionist attitude, focus on how people act, follow their stories, and see how the city is in motion.

Undine is the second film you’ve made with Paula Beer and Franz Rogowski, and it’s also the second part of a trilogy. When you met Paula and Franz, what convinced you that you could make three movies with them?

Christian Petzold: When I went into the scripting process, the fact that real people were chosen to portray the characters is both limiting and comforting to me. Your responsibility to both them and the story increases. I had a feeling with Paula and Franz that I had never experienced before.

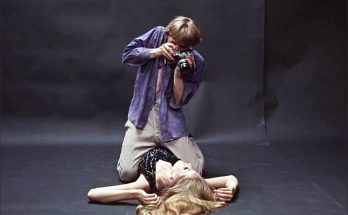

When they started to play, it was as if they were not only playing their roles, but were also dancing to a choreography. Neither of them comes from traditional acting schools. Neither of them had any acting training. At the same time, both have dance backgrounds. I guess this creates a secret connection between their bodies during filming. Watching them this way while filming, editing and watching the movie on the screen gives me a feeling I’ve never experienced before. I still want to watch them over and over again.

Franz Rogowski talked about your working style in an interview and said that you prefer to shoot every single shot. Is there any particular reason for your choice?

Christian Petzold: We rehearse for a long time to make it happen. At eight in the morning, the players wake up. Not earlier or later. Then they come to the set. When they come to the set, only me, the assistants and the actors have their costumes. We rehearse the scene for two or three hours. There is a small group still on the set and the actors do not have make-up on their faces, their hair is not done. There is neither a cameraman, nor an illuminator, nor an art director… No one will be inside.

We talk about what we want to do about that day’s scene and how we feel. After two or three hours, we now know who will do what on the stage, how to act and how to look, who will say what and how. Then we meet up with the rest of the team. We have the team watch a rehearsal with the seriousness of recording, and after this rehearsal, the players go backstage to complete their preparations.

At that time, I work on the storyboard of the scene with my cinematographer and the technical team. When we’re ready and the actors are back, I’d like to shoot the scene in one go. Because at that moment everything is very fresh. Of course, sometimes we do repetitions to shoot from different angles or because of a technical problem, but I prefer everything to be shot in a way that reflects the freshness of the first time.

It happens that players have problems with this choice. Because sometimes they want to repeat the scene, try something different, fix something they are not satisfied with, but everything is fine as it was at the first moment. I always tell the same story to my actors who ask me to shoot again. This is an incident that John Ford had with Henry Fonda during a shoot.

Ford didn’t like it when actors said, “Can we have it again” after a shoot? But Fonda was unaware of this. After a shoot, he said, “Can we get it again, I can do it better”. When Ford took a glance and replied, “Sure, you can start over”, the team was surprised at first by the director’s words. Finally, the plan was re-shot and Fonda said that he was more satisfied this time, but Ford took out the film reel on the camera and gave it to Fonda, saying, “You can take it and watch it at home.” When I told this story to Paula and Franz on set, Paula laughed out loud, and Franz tensed a bit.

We can argue that your relationship with architecture occupies a great place especially in Transit and Undine. In fact, architecture is the most important of all the other disciplines you interact with at Undine. What do you think about your perspective on architecture and the effect of architecture on the narrative of a movie?

Christian Petzold: When I decided to write about cinema in my youth, I realized how difficult it is to describe images and sounds, to describe them in words. Surprisingly, I found the words and terminology I was looking for in books on architecture. I came across an architect’s way of describing any building in his diaries.

These were almost integrating with cinematic expressions. The descriptions he used while describing details such as the way he describes a hall, the angle at which the light will enter through the windows, the calculations on which point of the house it will fall on, the relationship of the garden with the kitchen, the children’s room at the end of the corridors, made me realize that cinema and architecture have a lot in common.

Also, when I was a student at the German Cinema and Television Academy in Berlin, I attended a seminar on architecture and cinema given by one of our teachers, Hartmut Bitomsky. It is one of the most important seminars I have attended throughout my education life. During the seminar, Bitomsky made us watch David Lynch’s movie Blue Velvet – Blue Velvet and then asked us to answer the following questions: Where was the entrance to the garden, where was the kitchen of the house, where was the living room?

I remember thinking for a moment, “Why should we answer these questions?” However, just as an architect is concerned with the distance between elements such as rooms, doors, windows and beams in the building, we also took these elements into account when deciding where the actors, camera and sound team would be located. This mathematics was equally important when deciding on the mise-en-scène.

In fact, this was an element that shaped the mise-en-scène. Just as architecture determines the rhythm of the space, it can also affect the rhythm of the film. Sometimes I walk into a building and say, as if I’m commenting on a movie, it’s a terrible building, the lighting is wrong, the acoustics are wrong, the positioning of everything is wrong. Sometimes I walk into a building and feel like I’ve been affected by a movie.

All about Christian Petzold’s Undine movie.

Visits: 121