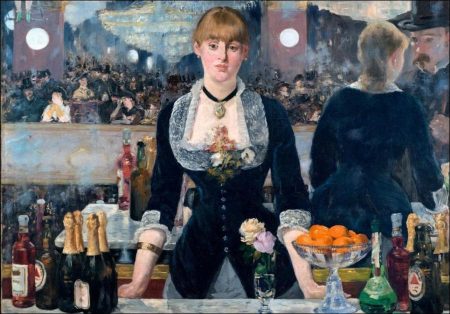

Everyone knows that staring at a woman’s cleavage is disrespectful. But in the case of Édouard Manet’s famous portrayal of a Parisian cabaret, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), our objectifying gaze has been deliberately orchestrated by the artist to nestle on a detail carefully positioned at the bosom of the barmaid. Here, Manet has planted in plain sight an underappreciated floral flourish that unlocks the power of one of the most intriguing and poignant paintings in all of modern art.

To understand the significance of that seemingly innocuous detail – a simple posy of red petals sculpted into a triangle – we first need to remind ourselves of the cultural context that Manet has chosen to depict, in what is widely regarded as the aging artist’s last major painting. At first glance, the scene may seem straightforward enough: a bored barmaid with faraway eyes awaits our order of spirits, champagne, or ale. In the expansive mirror behind her, the bustle of cabaret goers, whiling away a Parisian evening, ricochets from over our shoulders, fixing her inscrutable stare in a frozen flash of suspended hubbub.

Like a web that ensnares a fly, however, Manet’s masterpiece of complex perspectives will not allow our eyes to escape after a single glance. The awkward posture of another figure, standing with her back to us, just to the right of the young woman we’re facing, soon attracts our attention and begins to un-weave the simplicity of the painting’s geometry.

We suddenly realise that this figure, speaking to a stern-faced, top hat-wearing stranger, is actually a reflection of the barmaid we thought was gazing out at us. In fact, she is engaged in a hazy transaction with someone who, according to the logic of the painting, is standing precisely where we are. The barmaid’s eyes, whose emptiness we initially read as indifference, now appear more haunted than tired – as if their very life force was being siphoned from them.

But what exactly is the nature of the furtive exchange between the barmaid and the steely interloper, whose surreptitious presence Manet has consigned to the margins of his work? The venue depicted by the artist, as his Parisian contemporaries would have immediately recognised, was one where prostitutes plied their trade and barmaids moonlighted, turning tricks on the side. That the personhood of this particular barkeeper, who finds herself in the crossfire of ricocheted staring in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, is caught up in that exploitative economy, is suggested by the carefully constructed symbol that Manet has inserted at the very centre of his work: the corsage of red flowers, mentioned earlier.

Branded by a triangle

It would be easy to dismiss the triangular arrangement of the flowers as merely reinforcing a recurring geometric motif that echoes across the surface of the painting, rhyming as it does with the shape created by the bottom hem of the young woman’s black coat, with the upturned triangles of the chandeliers reflected in the mirror, with the triangular belly of the green bottle of absinthe in front of her, and the trilateral space created by the clasped yellow gloves of the woman in the upper left of the painting.

Once detected, triangles are indeed everywhere. A late decision by the artist to angle the barmaid’s arms in a downwards slope intensifies the prevalence of the trope. But the richest correspondence of triangularities in the painting, and the most troubling, is that between the young woman’s red triangular corsage and the corporate insignia printed on the labels of the two bottles of Bass pale ale – one on either side of her – that bracket the barmaid’s very being.

The distinctive red-triangle logo printed on the label of those bottles constitutes the very first officially protected trademark in the United Kingdom, registered by the Bass Brewery in 1876 – just six years before Manet created his painting. Predating by many decades Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup silkscreens and faux Brillo Box sculptures, Manet anticipates the product-placement preoccupations of the Pop Artists in a manner that makes those glossy icons of the 1960s seem even shallower by comparison.

To protect its proprietary product, Bass began searing into its barrels a red triangle – a corporate symbol that quickly became shorthand for the industrialised manufacturing and distribution of goods. The artist’s decision to affix his own signature to an adjoining bottle (on the left side of the painting), places beyond doubt his intention that observers of his work should equate the soulless labelling of a mass-produced commodity with the forging of human identity. By stamping the chest of his painting’s protagonist with an unauthorised replica of the Bass logo, Manet not merely marks her out as a consumable product to be bought and sold, he reduces her value further still by implying that her very existence is as disposable as a cheap counterfeit.

In a literal sense, of course, she is a counterfeit – as is every sitter of every portrait ever created. The woman whose shimmering and enigmatic presence we find so affecting is not real, but a painterly fabrication – a fantasy magicked into being by the alchemy of pigments and oil – a knock-off. As for us, standing in the very spot where the shadowy man who seeks to purchase the barmaid’s body is positioned, we too, as consumers of the work, are forever implicated in the tawdry transaction. He is us and we’re him – both traders in commodified souls, both forever on the verge of being smudged out of life’s frame.

Visits: 93