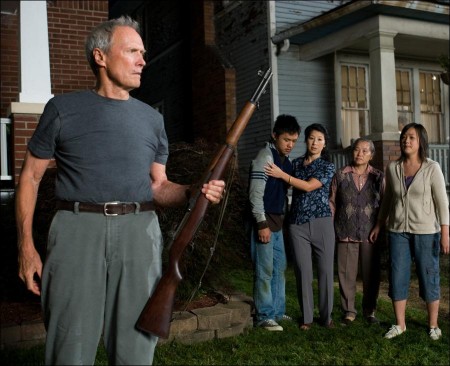

But Walt stands in the way of both the heist and the gang, making him the reluctant hero of the neighborhood-especially to Thao’s mother and older sister, Sue (Ahney Her), who insist that Thao work for Walt as a way to make amends. Though he initially wants nothing to do with these people, Walt eventually gives in and puts the boy to work fixing up the neighborhood, setting into motion an unlikely friendship that will change both their lives.

Through Thao and his family’s unrelenting kindness, Walt eventually comes to understand certain truths about the people next door. And about himself. These people-provincial refugees from a cruel past-have more in common with Walt than he has with his own family, and reveal to him parts of his soul that have been walled off since the war… like the Gran Torino preserved in the shadows of his garage.

They Don’t Make Them Like They Used To

Clint Eastwood, an actor and director whose body of work encompasses some of the most enduring and iconic films of all time, has not been in front of the camera since his 2004 Oscar-winning film, “Million Dollar Baby.” “I hadn’t planned on doing much more acting, really,” he says. “But this film had a role that was my age, and the character seemed like it was tailored for me, even though it wasn’t. And I liked the script. It has twists and turns, and also some good laughs.”

“Gran Torino” came to Eastwood’s producing company, Malpaso, from first-time screenwriter Nick Schenk, who wrote the script from a story he conceived with Dave Johannson. “This was based on their experience in Minnesota and people they knew,” comments Eastwood’s longtime producer and trusted partner, Robert Lorenz. “We got the script from Bill Gerber, who had received it from Jeanette Kahn. I read it fast, not necessarily thinking that it was something for Clint to act in, but about half-way through I slowed down and started to take it in. It was actually very good, so I read it a second time and just really liked it. I’ve learned never to oversell anything with Clint, so I gave it to him, saying, ‘I don’t know if you’ll want to make this or be in it, but you’ll enjoy reading it.’ And he called me and said, ‘I really liked that script.’ And it went from there.”

Schenk says the character of Walt Kowalski wasn’t written with a specific actor in mind, noting, “Walt’s a little bit of everybody’s shop teacher, or even your dad when he’s watching you reassemble your bike and screwing it all up. I think everybody knows someone like that.”

Originally from Minnesota, Schenk drew on his time working at a factory job with a number of Hmong families-the little-known culture from Laos and other parts of Asia that allied with the U.S. during the Vietnam War-that had settled there. “The Hmong culture is somewhat invisible,” he attests.

Walt, who slings racial slurs like most people use nouns and verbs, appears to be an unrepentant racist, but as he makes tenuous human connections with the Hmong people that have moved into his neighborhood, the layers of hostility peel away.

“Walt did things in Korea that haunt him, and he sees those faces in his neighbors,” Schenk remarks. “To Walt, all Asians are the same, all mixed in a blender. And so it just happens that here’s another culture that has no face, and as he learns more about them, he begins to reflect on what happened to him in his own experiences in Korea.”

Producer Bill Gerber notes that “Gran Torino” bears echoes of the relationships explored throughout Eastwood’s body of work. “Clint has always dealt with complex issues of race, religion and prejudice in an honest way, which can sometimes be politically incorrect but is always authentic,” he says. “But because of your familiarity with Clint, you understand that there’s more to Walt than what’s on the surface. You start in a fairly dark place, and then you begin to see who he is underneath because of his relationship with these people.”

“In retrospect, I can’t imagine anyone besides Clint Eastwood making this movie or playing this character,” adds Dave Johannson. “As a filmmaker Clint is very sparing and also doesn’t flinch, no matter how uncomfortable the subject matter. As an actor, it took a certain level of fearlessness to play Walt, who, to put it mildly, isn’t a very sympathetic character at first. Walt’s bigotry is something he has held onto for 60 years, and having the courage to change something about yourself that is so ingrained, particularly later in life, is a rare and difficult thing. Walt is a physically brave man, but the story forces him to show emotional courage.”

The story unfolds after the death of Walt’s wife, Dorothy, when he has reached the final chapter of a life that has in many ways been defined by haunting experiences in Korea and his 50 years at the local Ford plant. But now the war is long since over, the factory has been shut down, his wife has passed away, and his grown children barely have time for him. “Walt has worked hard and his sons have been reasonably successful,” says Eastwood. “He’s lost his wife, and he’s estranged from his grown children. They’ve gone off and left him, and he’s just kind of in the way. But in their defense, Walt’s not an easy case to handle because he’s so cantankerous, and, of course, the grandchildren have piercings and things, and he doesn’t approve of all that.”

“Walt’s very tough to have as a dad,” says Brian Haley, who plays Mitch Kowalski. “Mitch is the opposite of his dad. Walt is a hardworking blue-collar guy, and his son is a shallow suburban yuppie. They have a complex relationship. Walt doesn’t know how to talk to his son, and Mitch doesn’t know how to break through to his dad.”

Complicating Walt’s desire to be left alone is his late wife’s priest, Father Janovich, who is persistent in pursuing her final wish to have Walt take confession. “I joke that my part is basically to show up to the door and have Clint Eastwood slam it in my face,” says Christopher Carley, who plays the priest. “Father Janovich is trying to break through to Walt without any real knowledge of how to do it, or how to get Walt to even have a conversation with him. Walt is not impressed by the fact that he’s a man of the cloth. He just thinks of him as a ’27-year-old over-educated virgin.’ Walt makes it clear to him that the regular way of dealing with people is not going to fly with him.”

“Walt is probably prejudiced against the priest for lots of different reasons, but mostly because he looks like a kid,” says Eastwood. “He’s trying very hard to get Walt to confession, but Walt just thinks he’s a guy right out of seminary school with a book of ‘how-tos,’ and so it makes for a very one-way relationship. The ‘padre,’ as he calls him, is a determined young fellow, but in the end, Walt does it his way.”

One of Walt’s only real pleasures in life is shining up his Ford Gran Torino, built in 1972 and lovingly preserved beneath a silk tarp in his garage all these years. In fact, Walt himself installed its steering column during his time at the Ford plant. “The Gran Torino is his pride and joy,” Eastwood attests. “Walt sort of is the Gran Torino. He doesn’t do anything with it except let it sit in the garage. But every once in a while he takes it out. Walt with a glass of beer, watching his car – that’s about as good as it gets for him at this stage in life.”

In the midst of a run-down street of modest two-story houses, Walt’s home stands out, with its pristine paint job, neatly trimmed bushes and the American flag proudly displayed. He’s not happy with the turn the rest of his neighborhood has taken. “Walt’s a guy who is very, very disturbed about the way his world has gone,” says Eastwood. “He was raised in a neighborhood in Michigan that was populated with automobile people like he was, probably a high percentage of Polish Americans, like he is. So, when he sees his neighborhood changing, it discourages him.”

As the neighboring homes have deteriorated, Walt’s has been scrupulously maintained by a man used to working with his hands. “He’s the holdout in the community,” says Lorenz. “He’s somewhat stuck in the past in many ways. And emotionally, we learn that he has been stuck on something that hasn’t allowed him to progress as a human being. This dilemma is mirrored in every aspect of his life.”

Equally isolated is Walt’s neighbor, 16-year-old Thao, who is living in a house with his mother, grandmother and older sister. “He’s the only male in the household with no male role model to look up to or learn from,” describes Bee Vang, a first-time actor who won the role of Thao. “He’s awkward and unsure of himself as a guy because he’s surrounded by all these females who are domineering. He’s in need of a role model and finds this in Walt.”

Thao is a shy kid, out of high school but without a job, who finds himself pressured into joining an ad-hoc Hmong gang, led by a teen called Smokie and Thao’s cousin, who goes by the name Spider. “Everywhere Thao goes, somebody picks on him,” says Sonny Vue, who plays Smokie. “He can’t stick up for himself, so the gang would be there to back him up. Becoming a gang was really so they could protect each other from other gangs in the neighborhood. But things get out of hand when they feel threatened by Walt-they think they have to get tougher, that it will make them more manly.”

As first-generation Hmong Americans, Smokie and Spider don’t have their elders to guide them the way past generations of Hmong have, because their elders are having a harder time assimilating than they are. “You’re trying to live in two different cultures,” says Doua Moua, who plays Spider. “So there’s a lot of rebellion, and that makes a lot of male teens come together and create a group to try to assimilate in the world around them. A lot of the girls are more bonded to home and family, where their mothers can guide them, and they don’t have to rebel as much against their culture or their parents.”

The gang initiation Smokie and Spider devise for Thao is to steal Walt’s prized Gran Torino. “Thao is trying to prove that he can be manly and trying to find where he belongs,” says Vang. But the heist is short-lived, as Walt surprises Thao midway through it, scaring the teen off without seeing his face. “He fails pathetically at this attempt,” Vang adds, “and ends up being even more scared and humiliated by the time its over.”

Not long after, the gang comes back for Thao, resulting in a fight that spills over onto Walt’s front lawn. Wielding his M-1 rifle, left over from his combat days in Korea, Walt issues a warning to all involved: “Stay off my lawn.” “He goes back into his war mindset,” Eastwood offers. “That’s when he really starts to see the problems with the Hmong community, mainly the kids who join gangs.”

Walt’s unwitting bravery makes him the neighborhood hero, and his Hmong neighbors soon shower him with unwelcome gifts of food, flowers and plants. “He doesn’t want to have anything to do with these people,” Eastwood says. “He changes when he realizes they are intelligent and they’re very respectful of others, and I think he admires that. He has one line in the film where he says, ‘I have more in common with these people than I do with my own spoiled, rotten children’ and that kind of sums it up. It’s interesting, and often funny, how he starts out with a lot of prejudice, and then works his way out of it through these relationships.”

The only one to break through Walt’s prickly exterior is Thao’s spirited older sister, Sue, who is more Americanized than the rest of her family. “Walt is the kind of guy who will call you any names that he wants to,” says Ahney Her, who plays Sue. “He doesn’t care what race you are. He’ll say whatever he feels.” Her describes Sue as “a really brave character. She always talks nice to him, even though she does tease him with nicknames like ‘Wally,’ but ultimately she’s the person who is able to connect Walt and Thao together. I think Sue wants her little brother to become friends with Walt because if it goes the other way and he gets in with the gang members, he’s just going to mess up his life. She sees that Walt can be like a father, and if Thao listens to Walt, he could probably be led to a better life and a better way of growing up.”

Walt and Sue form an easy and light rapport. “She seems to genuinely care about him in a real way, not a phony way, like some of his family members who seem to be just going through the motions and doing what they’re supposed to do,” Lorenz says. “I think her sincerity appeals to him and he allows himself to get to know her a little bit.”

Eventually, Sue is able to lure Walt over to her house for a family celebration, where an encounter with a Hmong shaman puts words to the unspoken truths Walt has been living with all these years. “The thing about the Hmong family-which comes completely into focus in that exchange with the shaman-is that they’re willing to say what has been unspoken in Walt’s own family,” Lorenz notes. “They’re willing to draw attention to some things and ask him probing questions that make him reflect on himself more than anyone else has challenged him to do before. That’s the heart of his racism-a selfish inability to look at himself. Instead, he projects outward at everyone around him, trying to see his problems as things that others have caused, rather than looking inward to see how he can change and adapt, and these folks force him to do that in some way.”

To make amends for the near-theft of Walt’s car, Thao’s mother and sister pressure him into helping out Walt with odd jobs for a couple of weeks. “They want him to make restitution,” says Eastwood. “That’s part of their family pride.”

Walt’s initial response is to call the boy a litany of racist names, deliberately misspeaking his name as “Toad.” But as the boy earnestly throws himself into Walt’s missions to fix up the deteriorating houses peppering the street, Walt begins to glimpse something in the young man worthy of more than his scorn. “You start to see that their relationship is evolving,” says Vang. “Walt starts to appreciate him as things begin to develop with Thao, who is obviously growing and changing from the young boy he was when they first met. And now, with Thao having calluses all over his hands, he’s proud that he has finally accomplished something useful-that he is useful.”

The purpose of Walt’s work with Thao, continues Vang, is to “man him up. Walt’s not there just to teach him how to work, but also how to stand up for himself so that he doesn’t have to join a gang to feel like a man. Walt is the man who is helping Thao develop more of a backbone.”

Walt’s ultimate goal becomes to empower the aimless kid to get a job and stay out of trouble so he can have a future, but their oddball relationship also ends up changing Walt himself. “Thao doesn’t have a father figure to rely on and give him guidance, and Walt never had a real connection with his own sons that might have given him that satisfaction of fatherhood,” says Lorenz. “It’s sort of a perfect fit for each of them. Walt is also searching. He clearly knows that he’s in the last chapter of his life, and he’s searching for someone or something to make sense of it all and to calibrate the value of his life.”

Through it all, Smokie and the gangbangers continue to harass Thao and his family, ratcheting up the threat of violence, and forcing the old warrior to take on an entirely new and unexpected mission. “If you just do something half-way, then it becomes a Hollywood bailout,” says Eastwood. “And if you’re gonna play this kind of guy, you can’t go soft with it. You gotta go all the way.”

The Strangers Next Door

“Gran Torino” marks the first major motion picture to portray characters from the Hmong community-an ethnic tribe of 18 clans spread among the hills of Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, and other parts of Asia-who made a difficult transition to the United States following their involvement in the Vietnam War. “I didn’t know too much about them,” admits Eastwood. “Because they had helped the Americans during the conflict, they were brought here as refugees after the end of the Vietnam War.”

“Part of the tragedy is that a lot of people don’t understand the role the Hmong people played in the Vietnam War,” says Paula Yang, a Hmong adviser the filmmakers consulted early on. “How we came to the United States, and how many of our soldiers and civilians were lost during the war, remains a secret. The elders don’t talk about it. They’re so humble and there are so many sad stories.”

Eastwood points out that the Hmong identify themselves as a culture with its own unique heritage, as opposed to a nationality. “They have their own religions, their own language, and they consider themselves their own people,” he explains. “A lot of them have been through many hardships following the Vietnam War. Things weren’t very pleasant for them over there, and so the Lutheran church and a lot of individual organizations worked hard to get them over here. But they withstood a lot of sadness, so they’re tough, very determined people.”

Eastwood wanted to portray the Hmong in “Gran Torino” as authentically as possible, starting with casting an exclusively Hmong cast for those roles in the film. But casting director Ellen Chenoweth soon discovered there weren’t many professional Hmong actors listed at SAG.

Chenoweth and her casting associates Geoffrey Miclat and Amelia Rasche cast a wide net and researched on the internet to find hubs of the Hmong community. They made contacts and distributed flyers in Fresno, California; St. Paul, Minnesota; Warren, Michigan; and throughout other areas of the U.S. “This involved a lot of digging,” notes Chenoweth, “a lot of getting to know the Hmong communities, making inroads, gaining their trust, and finding out who wanted to be in a movie. It wasn’t done through the normal channels. This was really going to them and opening ourselves up to them.”

Hmong cultural advisor Cedric Lee helped the casting team with outreach throughout the community. “We’d go to places where Hmong people hung out,” he remembers. “We went to Father’s Day parties. We went to church events. There’s a language barrier, especially for the elders, so we would speak Hmong and then translate to the casting directors. With the youth it’s a lot easier, because a lot of them are English-speaking.”

Chenoweth and her team started with community leaders in St. Paul and Fresno, and then conducted a series of open casting calls everywhere that Hmong had settled, culminating in a huge, day-long open audition in St. Paul.

Word spread of Eastwood’s film through Hmong communities online, through newspapers, youth groups and word of mouth. “People were so excited,” says Paula Yang. “It was Clint Eastwood, so people were going to do whatever they could. We had old kids, young kids, old grandmas and grandpas. People were excited because Clint was making this opportunity for our Hmong people.”

Soon they had hundreds of auditions on tape. “After we visited each city, we would come back to Los Angeles to go over all the tapes with Clint,” Chenoweth explains. “We’d put them up on the screen in his editor’s room and started narrowing down our choices until we had several candidates for each role, and then he made his decisions.”

From hundreds of prospects, Eastwood cast 16-year-old Bee Vang from St. Paul in the central role of Thao. Chenoweth remembers, “Amelia found him through his school, and on his picture I wrote, ‘I heart Bee Vang.’ I just loved his face. He had very little acting experience, but had this quality that was so open and sweet. You just wanted him to be okay. When I called Bee Vang and told him we wanted him for Thao, he couldn’t even talk for a while. I think it was something that he hadn’t ever really dreamed of.”

At 5’5″, Bee Vang’s Thao stands in stark contrast to Eastwood’s 6’2″ Walt. “Thao is literally always looking up to Walt,” says Vang. The Fresno-born teen attended a private audition for the film in the Twin Cities. When he found out he’d won the key role of Thao, “I got down on my knees and started crying,” he relates. “The whole thing was really life-changing. I couldn’t believe this was happening to me.”

Though initially intimidated, Vang soon grew comfortable with Eastwood’s low-key style. “Growing up, I’d seen him in Westerns and other films, like ‘Dirty Harry,’ but I never imagined that I’d ever even meet this guy, and then there he was,” he says. “Mr. Eastwood likes things to be as natural as they can be. It has to be real. I like that style. He’s a really nice guy, too, a really humble guy. I loved every minute working with him and the rest of the crew. I will never forget this.”

Sixteen-year-old Ahney Her beat out hundreds who auditioned for the role of Sue. Amelia Rasche had set up a booth at a Hmong fair in the Detroit area, with a big sign on it saying, “Hmong Movie Casting.” “Ahney and her family walked by and Amelia literally ran over and grabbed her and said, ‘Do you want to try out for a movie?'” Chenoweth recounts.

Her’s confidence and humor made her a natural for the role of the Thao’s older sister. “We wanted the sister to have a slightly tougher edge. She’s protective of Thao, who is more vulnerable,” says Chenoweth. “Ahney definitely had that along with a great kind of youthfulness about her that we all loved.”

Her’s rapport with Eastwood was not much different from Sue’s and Walt’s, giving the acting novice added confidence in her first big role. “He’s very humble and easygoing,” she says. “He likes to make you comfortable and is not the type to tell you exactly what to do. He wants you to do whatever you feel is right, and if it’s not right in his eyes, then he’ll tell you. He’s a great man, and it was amazing to work with him.”

“Bee and Ahney both seemed to take to acting very naturally because they had great natural qualities anyway,” says Eastwood. “I’d like to take a lot of credit for it, but it really wouldn’t be justified.”

The role of Vu, the single mother of Thao and Sue, is played by Brooke Chia Thao, who was born in Laos and settled in Visalia, California. Chia Thao had no acting training, and was actually bringing her own kids to the audition when she was cast. “She just happened to be there, so we asked her to audition and she landed the role,” recalls Cedric Lee. “The funny thing is she’s pretty Americanized, but when you see her as the mother, it’s like two completely different people.”

For Chia Thao, the film represents a chance to shine a light on her people. “The movie doesn’t really represent the whole Hmong culture, but it gives a little taste of it,” she says. “I hope that people start to see us in a more unique way, who we are and how we helped in the war. My own father was recruited to fight for the U.S. when he was only 14.”

Chee Thao, the 61-year-old who plays the family grandmother, was born in Laos and now lives in St. Paul. “Casting the grandmother was an interesting challenge because the character spoke entirely in Hmong,” says casting associate Geoffrey Miclat. “A lot of it was just personality. Grandma is a very funny character, and there was this quality about Chee that made her perfect for the role.”

Thao felt a special bond with Eastwood, and spent time talking with the actor/director, with her granddaughter serving as translator. Having lived through a tragic past, she poured her heart and soul into her performance. “Chee Thao said that it was no trouble for her to get into this character because it was her,” says Lorenz. “She has had all these struggles that are portrayed in the film. So when she was out there, basically ad-libbing her way through a lot of the scenes-because a lot of the Hmong dialogue wasn’t spelled out-it was no trouble. She just said all the right things; she brought her own story to it.”

Five Hmong actors from several states and different clans of Hmong were cast as the boys who make up the gangbangers that menace Thao and his family in the film. “There was just a realness about these guys and they had such great faces,” says Miclat. “Once we saw Doua Moua in New York, and Sonny Vue in St. Paul, we had a pretty good feeling that they would be our Spider and Smokie. And Doua Moua was actually one of our few Hmong cast members with acting training, so we knew he was going to fit somewhere.”

Moua, who moved to New York City when he was 18 to pursue an acting career, was cast as Thao and Sue’s cousin, Fong, who now calls himself Spider. Born in Thailand, Moua grew up in Minnesota and was one of the only Hmong cast members with acting experience. “‘Gran Torino’ is a dream come true for me,” he says. “I appreciated every moment that I was on set. Clint was amazing to work with, really laid back.”

Sonny Vue, born in Fresno and now from St. Paul, plays the leader of their group, Smokie. At 19 years old, Vue had never been in front of a camera before but was such a natural the casting directors grabbed him from the front desk. “I was talking to the lady at the front counter, and Amelia [Rasche] came up out of nowhere,” he recalls. “She was like, ‘Do you want to audition for the role?’ So, I tried, and I got the part.”

The other members of the Hmong gang are played by: Lee Mong Vang, from Toledo, Ohio; Jerry Lee, from St. Paul; and Elvis Thao, who lives in Milwaukee and is a member of the hip hop group RARE. Elvis Thao was also thrilled that Eastwood used one of RARE’s songs on the “Gran Torino” soundtrack.

Outside of the Hmong cast members, one of the key roles was that of Father Janovich, the earnest Catholic priest who tries to break through to Walt to fulfill Walt’s late wife’s dying wish.

Cast in the role, Christopher Carley seemed to embody the qualities Eastwood sought for the priest. “When we saw Christopher Carley, he just looked like a priest,” Chenoweth explains. “He had this open Irish face, red hair. I thought he was really good, and when I showed his tape to Clint, he said, ‘He looks like a young Spencer Tracy.’ I knew he was going to cast him at that point. Clint didn’t care about having an established star in that role; he’s just really open to giving a chance to people who are perhaps less well-known in the industry.”

“I do like to give people a break,” says Eastwood. “I like to see new people come along, and have opportunities. But, by the same token, it’s important to do whatever suits the film. If somebody who’s well known fits the role, then I go for it. If I can use somebody lesser-known who happens to suit the role, then that’s fine, too. There’s no real rule to it. Every picture has its own structure, and its own personality.”

Carley’s impression of Eastwood’s working style mirrors that of his fellow cast members. “He’s very calm and focused, and there’s a large element of trust on the set between Clint and the actors,” Carley describes. “You feel like it’s a safe place to show up, being prepared and knowing that whatever choice you make, you’re not going to have to fit into some tiny little box that has been pre-designed.”

Rounding out the cast are John Carroll Lynch as Martin, Walt’s barber, who trades good-natured racial epithets with Walt and helps coach Thao in the fine art of “manning up”; Brian Haley as Walt’s elder son, Mitch; Geraldine Hughes as Mitch’s wife, Karen; Brian Howe as Walt’s second son, Steve; and William Hill as construction foreman Tim Kennedy, an old friend Walt enlists to help him give Thao better options in his life.

The prized Gran Torino was played by the real thing, out of Vernal, Utah. “We got lucky right off the bat because it was one that worked,” says transportation coordinator Larry Stelling. “It was completely maintained and Clint really liked it. We did a couple of things to it, like replacing bumpers and things like that, but other than that just sparkled it up a little bit. The color was fine, great interior, and it ran great.”

The production purchased the car and brought it to Michigan for principal photography, but its story may not end there. “We were talking about selling it locally when we were finished, but as the movie progressed, we all became rather fond of the car,” recalls Lorenz. “I asked Clint about it and he said, ‘Well, let’s hold on to this car. It has done right by us, so let’s see what happens.'”

Cameras Roll in Motor City

Though the screenplay was initially set in Minneapolis, Eastwood felt Walt’s past as a 50-year auto worker would resonate most as a resident of “Motor City”-Detroit, Michigan. Production set down in locations including neighborhoods of Royal Oak, Warren and Grosse Point, with the once affluent Highland Park standing in for Walt’s own neighborhood.

“The neighborhood of Highland Park has changed,” Eastwood comments. “It used to be a big neighborhood of all automobile people-families that were all interconnected somehow when the automobile manufacturers were in their heyday. The factories are now not as active as they used to be, but the new people that are moving in are quite comfortable there. Highland Park has gone through its hard times, but there are a lot of nice people living there.”

Rob Lorenz notes, “We were there for several weeks in this neighborhood doing construction and so forth and then shooting, and we tried to have as little impact as possible. The people we interacted with were thrilled to have us.”

Part of the economy and artistry of Eastwood’s films can be attributed to the respect and loyalty the filmmaker inspires from his close team of collaborators. Though he never raises his voice, never says, “Action,” and encourages autonomy, Eastwood is always in control. “Clint is very comfortable in his own skin,” attests Tom Stern, making his seventh film with Eastwood as director of photography, following many more as chief lighting technician. “He told me before we started, ‘I am my age. This is who I am.'”

But his team considers his age and experience part of the alchemy that makes him such a singular visionary filmmaker. His unique approach and the well-oiled mechanism of his team allow him to move deftly through the production schedule.

Reuniting on “Gran Torino” are his other longtime collaborators: costume designer Deborah Hopper, editor Joel Cox, and production designer James J. Murakami, who worked with the legendary Henry Bumstead on Eastwood’s prior films before taking the leading role as production designer on “Changeling.”

“I’m familiar with their work, they’re familiar with my work, so we don’t have a lot of explaining to do,” Eastwood states. “It’s always built around eliminating as much intellectualizing or discussion as possible. There’s enough discussion when you’re making a film without adding more to it and making it more complicated than it is. I’m not one of those guys who likes to show that there’s a lot of magic in it. If there is any magic in filmmaking, it should be very subtle. But, for the most part, it’s just everybody doing a good job and participating. It’s a fun process. When it’s not fun, you won’t see me doing it anymore.”

“Gran Torino” also marks the seventh Clint Eastwood film Rob Lorenz has produced, and fellow producer Bill Gerber attests, “Clint couldn’t ask for a better producing partner than Rob. Looking at locations with the two of them and seeing the stuff that Rob had pre-selected, there was so little back and forth. Rob just knew what Clint wanted. They have a great relationship, and the Malpaso machine is an extraordinary one. It purrs along well.”

“Clint is old school and he recognizes the value of the old ways of doing things, because he has been around long enough to see them work,” Lorenz remarks. “At the same time, he embraces new technology and wants to keep learning, moving forward and progressing. That’s really what drives him, and I think that’s why he’s such a pleasure to work with.”

An example of Eastwood’s innovations is a wireless portable video monitor he had tailor-made for him to allow maximum efficiency in directing scenes in which he’s also a player. “It allows me to actually see the scene as it’s going on, without having to squint through the camera,” he explains. “I can be half a block up the street and see what’s going on.”

For the two key houses in the story-Walt’s house and the home of Thao and Sue next door-the location managers and production designer managed to find two neighboring houses that fit all the requirements. “What we were looking for in Walt’s house was a house that could look like a person had cared for it all his life,” Lorenz describes. “We ‘aged’ the rest of the homes on that street to show the disrepair that had taken over the houses around him. Jim’s sense of what both houses should look like was so well-developed that he and his set decorator, Gary Fettis, set to work immediately. By the time Clint got there to see it, he took a walk through each of the houses and said, ‘I love it. Don’t change a thing.’ It was perfect.”

To inspire the design for Thao and Sue’s house, Murakami researched through photographs and visited numerous Hmong households. “We brought in our technical adviser and she was just in awe because everything made perfect sense,” says Lorenz. “She had a couple of minor changes but overall told us, ‘You nailed it.'”

Likewise, costume designer Deborah Hopper did internet research and attended a Hmong festival where she consulted numerous vendors to help ensure authenticity in the Hmong costumes. “We attended the festival where the Hmong women would buy their contemporary and traditional Hmong clothing,” Hopper notes. “One of the things I learned is that the mothers teach their daughters how to make their traditional clothes. In fact, Ahney Her brought in her own handmade costume for research for the film.”

In addition to the “Soul Calling” ceremonies at the house, Sue and Thao also have occasion to wear their traditional ceremonial costumes to honor Walt. “They’re very ornate,” Hopper describes. “They have coins hanging all over them, which signify the wealth of the family. The ceremonial dress is also very colorful: the women wear turbans and the men can wear a vest or cross-belts. I thought they were so unique and beautiful. It was something I had never seen before.”

The blend of cultures in “Gran Torino” is also reflected in the music. Eastwood’s own connection to music makes the score and soundtrack of particular importance to the filmmaker, who conceives basic sounds and melodies for his films as he shoots them. “You just hear different sounds for a picture, and then work them out on the piano, write them down, or orchestrate them,” he explains.

“Sometimes I’ll have somebody else do it; sometimes I do it myself. There’s no rule there. It’s just when you hear it, it feels right.

“It’s nice when you get to the music part because you are no longer shooting the film, the film is what it is,” Eastwood continues. “So, then, you’re enhancing the film. You do music, sound effects, all that sort of thing. It’s exciting when all of a sudden you go from working with 50, 60, 70 people down to one or two people in a room with an Avid computer.”

The title song for “Gran Torino” is performed by British jazz singer/pianist Jamie Cullum and Don Runner. It was co-written by Eastwood; Cullum; the director’s son, Kyle Eastwood; and Kyle’s writing partner, Michael Stevens. “Together they came up with the song,” Lorenz relates. “And then Kyle and Mike used that as an inspiration for the music throughout the rest of the film.”

Kyle Eastwood and Michael Stevens composed the score, which was then orchestrated and conducted by Lennie Niehaus, whose association with the director dates back to the film “Tightrope.”

The soundtrack also includes Hmong and Latino rap, reflecting what the characters are listening to, including one track by cast member Elvis Thao’s rap group, RARE. “Some of the folks that came in to read were rappers,” says Lorenz. “Some did get roles and some didn’t, but they all submitted their music. It was so appropriate, so we put as much as we could throughout the movie.”

In every aspect of production, the Hmong community as a whole ultimately provided tremendous support to help bring a unique and truthful coloration to the project. In addition to casting, Hmong advisers assisted with dialogue, customs and design elements, and Eastwood hired numerous Hmong artisans and assistants to work as part of the crew.

“They wanted to be a part of this film and were so generous to us,” Eastwood states. “It was a real pleasure for me to work with them. I hope the Hmong people are happy with the way the film tells some of their story through Walt’s eyes.”

With “Gran Torino,” Eastwood adds Walt Kowalski to his legacy of indelible characters. “Clint is always interested in progressing and not doing something that he has already done,” Lorenz reflects. “This script seemed to offer just that. It suited him in terms of his age and his character, and it seemed to draw from his past, his life as Dirty Harry and the outlaw, the hard-edged, uncompromising character. And yet it advances further. It takes him into a little bit darker territory, but also allows him, through his character’s redemption, to explore something new.”

Production notes provided by Warner Bros. Pictures

Gran Torino

Starring: Clint Eastwood, Cory Hardrict, Brian Haley, Brian Howe, Dreama Walker, Christopher Carley

Directed by: Clint Eastwood

Screenplay by: Nick Schenk

Release Date: January 16, 2009

MPAA Rating: R for language throughout, and some violence.

Studio: Warner Bros. Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $145,304,147 (70.5%)

Foreign: $60,900,000 (29.5%)

Total: $206,204,147 (Worldwide)