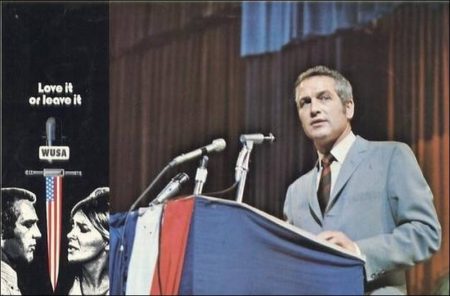

Taglines: Love it or leave it.

WUSA movie storyline. Reinhart (Paul Newman) drifts into New Orleans and rescues Geraldine (Joanne Woodward), from a pimp’s knife, buys her a steak and they shack up. He gets a job at WUSA, a right-wing radio station as a news, sports and weather reader. Their neighbor, Rainey (Anthony Perkins) is a do-gooder who is doing a survey of welfare applicants without knowing that his boss, Bingamon (Pat Hingle), works for WUSA and the whole study is intended to gather evidence needed to kick people off welfare, not help them as he supposes. Geraldine wants to be loved but Reinhart is inaccessible, burnt out. She mothers Rainey, a stuttering boy who reminds her of the boy she loved, the boy who shot himself.

When Rainey finds out he’s been duped he goes to WUSA and threatens the owner. He confronts Reinhart who tells him in two words to drop dead. Rainey gets a rifle and attempts an assassination of the radio station’s owner at a rally festooned with red, white and blue bunting. Reinhart and his friends are onstage. One of them, knowing the police are coming, puts his stash of grass in Geraldine’s purse. In the panic, Rainey is shot dead and Geraldine arrested for possession. There, in prison, she commits suicide. The news is delivered by Philomene (Cloris Leachman), Geraldine’s friend.

WUSA is a 1970 American drama film directed by Stuart Rosenberg and starring Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Anthony Perkins, Laurence Harvey, Cloris Leachman and Wayne Rogers. It was written by Robert Stone, based on his 1967 novel A Hall of Mirrors. The story involves a radio station in New Orleans with the eponymous call sign which is apparently involved in a right-wing conspiracy. It culminates with a riot and stampede at a patriotic pep-rally when an assassin on a catwalk opens fire.

Film Review: Reconsidering WUSA forty years later

I’ve always had a soft spot for literary and cinematic evocations of New Orleans. Filmed in black and white, set to Tom Waits’s “Jockey Full of Bourbon,” the shots of the city that open Jim Jarmusch’s Down by Law rank among my favorite few minutes of any movie. Despite the cheesy voodoo and dead chickens, I love Angel Heart, and I remember being taken by the atmosphere even in a relatively silly evocation of the city like the crime caper The Big Easy. In 1997, when I read A Confederacy of Dunces, I’d just moved to New Orleans and was staying at the YMCA on Lee Circle. If I hadn’t been living in the city, the characters in the novel might have seemed comic, not to say overdrawn. As it was, I read the novel as a realistic one, since I saw people like the characters in the novel every night.

I lived in New Orleans from 1997 to 2000, and it took me most of a decade to write about the city; most of my attempts fell too easily into the sort of clichés one encounters about New Orleans—the alcohol, the drawl, et cetera. My father’s stories make Uptown New Orleans seem like a countercultural heaven when my parents lived there in the 1960s; they also make the clashes between counterculture and law enforcement at the end of the decade seem outright dangerous, policemen beating up hippies in the French Quarter as much a sign of the times as the 1968 Democratic National Convention or later, the Kent State shootings.

When I first visited, in 1994, a flyer outside a bar on Decatur Street compared the number of murders in New Orleans and Jerusalem; that year, “including Hamas bombings,” each city had experienced upwards of 360. Though the events following Hurricane Katrina affected residents of the city in ways most outsiders cannot begin to comprehend, the storm also constituted a national tragedy, a tragedy that tells us about the fabric of the nation as much as it does about the politics of a particular place.

One of the great joys of Stuart Rosenberg’s WUSA, his 1969 adaptation of Robert Stone’s A Hall of Mirrors, is the way it evokes the New Orleans that was still visible but disappearing even when I lived there in the late 1990s—the Canal Street department stores, the French Quarter dives, the jazz clubs, the bars with wood paneling. If that New Orleans resembled anything, it resembled the blue collar city that disappeared when the dot com boom remade San Francisco in the early 1990s.

Indeed, things have changed in the decade since I left; that YMCA where I spent four nights in 1997 is long gone, as is the Hummingbird Grill, an all-night diner on the ground floor of a residential hotel where ex-cons worked the grill, and the waitress brought you a thermos when you ordered coffee. Certainly, Rosenberg’s jingoistic right-wing media outlet—the titular radio station, peopled by hucksters and conmen who may or may not mean what they’re saying—seems prescient.

Though the inevitable comparisons with Fox News might be a bit overblown, insofar as Paul Newman’s Reinhardt, the dissolute disc jockey at the center of the story, is far more charismatic than anyone on Fox. Oddly, though, the film can’t seem to make up its mind whether it wants to glorify or condemn Reinhardt’s moral apathy. In fact, apart from fringe elements on both sides of the political spectrum, moral apathy seems to be the defining characteristic of just about everybody in the movie. As in Yeats’s poem, in WUSA, only the worst are full of “passionate intensity.”

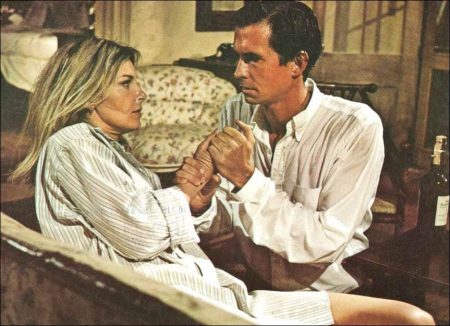

Briefly, the story goes as follows: An alcoholic drifter, Reinhardt, washes up in New Orleans. He meets Geraldine (Joanne Woodward), also a drifter, on the run from a pimp who scarred her face in Houston; though she looks for work as a waitress, when nothing pans out, she solicits men in bars. Eventually, the two pair up, and Reinhardt finds work as a disc jockey on WUSA; though he identifies as “liberal,” as long as there’s a paycheck involved, he doesn’t mind reading news with a conservative, openly racist spin.

In short order, Reinhardt and Geraldine move into an apartment in the French Quarter, in the same building as a group of disaffected hippies and Rainey (Anthony Perkins), a young, liberal southerner (a judge’s son, we discover) who after a stint in Venezuela with the Peace Corps, has come home and started collecting data on New Orleans welfare recipients for some vague municipal entity. When they meet, Rainey excoriates Reinhardt for working for WUSA.

Far more charismatic and verbally adept than Rainey, Reinhardt wins the argument handily, though he upsets Geraldine by mocking Rainey’s idealism, which he characterizes as self-aggrandizing. Shortly thereafter, Rainey discovers the survey he’s been conducting is a sham. In fact, he’s working for the same people who own the radio station, and the data he’s collecting will be used to fuel the campaign of an up and coming conservative politician who wants to kick African-American welfare recipients off the dole.

In Stone’s novel (he also wrote the screenplay), the three major characters exude a palpable sense of desperation that propels the reader through the more hallucinatory parts of the narrative. In the film, though dissipated, Newman (being Newman) manages to make Reinhardt look and sound cool; in fact, he turns in such an effortlessly charismatic performance, and he’s such a pleasure to watch, it’s almost a problem, since the apathy he makes so appealing runs contrary to what would seem to be the movie’s own left-leaning political inclinations.

When he’s not with Geraldine or working at the radio station, Reinhardt spends most of his time drinking and getting high with the hippies downstairs, who seem unfazed by his willingness to betray his principles for a paycheck. Along with Reinhardt, they sneer openly at Rainey, the idealist. In one scene, when Rainey shows up at their apartment to see Reinhardt, one of the hippies asks if Rainey’s “cool.” Reinhardt jokingly replies that Rainey’s not necessarily “cool,” but he won’t bust them for the dope they’re smoking, which is all anyone’s concerned about anyway.

In that regard, perhaps inadvertently, Newman’s charisma, his on-screen chemistry with Woodward, and the fact the film’s plot confirms Reinhardt’s cynicism, all cause the film to express a worldview much closer to Reinhardt’s cynical, self-interested libertarianism than it is to Rainey’s sincere, if somewhat patronizing liberalism—which is a problem, since the movie clearly wants us to sympathize with Rainey’s convictions, if not with him as a person. If this constitutes one of WUSA’s chief failures, nevertheless, it also makes the movie deeply suggestive of the contradictory philosophical underpinnings of American counterculture, and it’s one of the chief appeals of a film otherwise remarkable for proving the biggest flop of Paul Newman’s career.

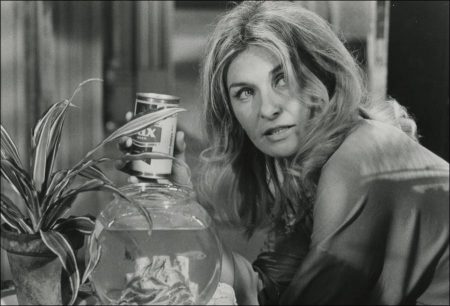

In WUSA, apart from the shady conservative politicians and business owners behind the radio station, only Geraldine and Rainey seem possessed of any moral conviction, and it destroys them. In a small but significant departure from the novel, Rainey—by now dangerously unstable, as wounded idealists tend to be—becomes not just complicit in but actually touches off the orgy of violence at the climax of the movie. For her part, Geraldine’s vulnerability—her humanity—makes her a victim.

When she’s busted with a quantity of marijuana the hippies downstairs have hidden in her purse—an act of cynicism that makes them complicit in her death in ways the film never explores—rather than face Louisiana’s draconian penalties for possession of marijuana, she takes her own life. Over a song Neil Diamond wrote for the soundtrack, in a montage, Reinhardt walks (stumbles) through a derelict graveyard, apparently grieving Geraldine. In the movie’s final scene, ruefully yet somehow boastfully, Reinhardt tells the priest and onetime conman he followed to New Orleans at the beginning of the movie that he—Reinhardt—is “a survivor.” Then he flings his jacket over his shoulder and walks out the door, presumably to board yet another Greyhound to yet another city.

WUSA (1970)

Directed by: Stuart Rosenberg

Starring: Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Anthony Perkins, Laurence Harvey, Pat Hingle, Don Gordon, Michael Anderson Jr., Leigh French, Bruce Cabot, Cloris Leachman, Moses Gunn, Wayne Rogers

Screenplay by: Robert Stone

Production Design by: Austen Jewell, Arthur S. Newman Jr.

Cinematography by: Richard Moore

Film Editing by: Bob Wyman

Costume Design by: Travilla

Set Decoration by: William Kiernan

Art Direction by: Philip M. Jefferies

Music by: Lalo Schifrin

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for mature thematic elements involving violence, drug and alcohol use, sexual content and nudity.

Distributed by: Paramount Pictures

Release Date: August 19, 1970

Views: 208