Rome, Open City movie storyline. The location: Nazi occupied Rome. As Rome is classified an open city, most Romans can wander the streets without fear of the city being bombed or them being killed in the process. But life for Romans is still difficult with the Nazi occupation as there is a curfew, basic foods are rationed, and the Nazis are still searching for those working for the resistance and will go to any length to quash those in the resistance and anyone providing them with assistance.

War worn widowed mother Pina is about to get married to her next door neighbor Francesco. Despite their situation – Pina being pregnant, and Francesco being an atheist – Pina and Francesco will be wed by Catholic priest Don Pietro Pelligrini. The day before the wedding, Francesco’s friend, Giorgio Manfredi, who Pina has never met, comes looking for Francesco as he, working for the resistance, needs a place to hide out.

For his latest mission, Giorgio also requests the assistance of Don Pietro, who is more than willing as he sees such work as being in the name of God. Don Pietro’s position also provides him with access to where others are not able. Giorgio’s girlfriend, Marina, a cabaret performer, doesn’t even know where Giorgio is in hiding. Both Pina and Marina take measures to improve their lives under this difficult situation, those actions in combination which have tragic consequences.

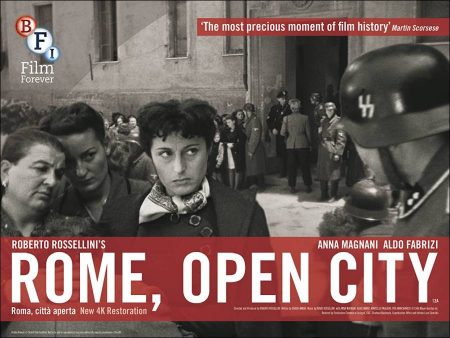

Open City or Rome, Open City (Italian: Roma Città Aperta) is a 1945 Italian neorealist drama film directed by Roberto Rossellini. The picture features Aldo Fabrizi, Anna Magnani and Marcello Pagliero, and is set in Rome during the Nazi occupation in 1944. The title refers to Rome being declared an open city after 14 August 1943. The film won several awards at various film festivals, including the most prestigious Cannes Grand Prix and was nominated for the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar at the 19th Academy Awards.

By the end of World War II, Rossellini had abandoned the film Desiderio because conditions made it impossible to complete (it later was finished by Marcello Pagliero in 1946 and disowned by Rossellini). By 1944, there was virtually no film industry in Italy and no money to fund films. Rossellini had met and befriended a wealthy, elderly lady in Rome who wanted to finance a documentary on Don Pieto Morosini, a Catholic priest who had been shot by the Germans for helping the partisan movement in Italy. Rossellini wanted actor Aldo Fabrizi to play the priest in reenactments and contacted his friend Federico Fellini to help get in touch with Fabrizi.

By then, the lady had agreed to finance an additional documentary about Roman children who had fought against the German occupiers. Fellini and screenwriter Sergio Amidei suggested to Rossellini that, instead of two short documentaries, he should make one feature film that combined the two ideas, and in August 1944, just two months after the Allies had forced the Nazis to evacuate Rome, Rossellini, Fellini, and Amidei began working on the script for the film.

The devastation that was the result of the war surrounded them as they wrote the script. They titled it Roma, città aperta and declared publicly that it would be a history of the Roman people under Nazi occupation. Shooting for the film began in January 1945. The funding from the elderly Roman lady was never enough, and the film was crudely shot due to circumstances and not for stylistic reasons. The facilities at Cinecittà Studios were also unusable at that time due to unreliable electricity supply and poor quality film stock.

New Yorker Rod E. Geiger, a soldier in the Signal Corps, who eventually became instrumental in the movie’s global success, met Rosselini at a point when they were out of film. Geiger had access to the film units at the Signal Corps that regularly threw away short-ends and complete rolls of film that might be fogged, scratched, or otherwise deemed unfit for use, and was able to obtain and deliver enough discarded stock to complete the picture.

In order to authentically portray the hardships and poverty of Roman people under the occupation, Rossellini hired mostly non-professional actors for the film, with a few exceptions of established stars including Fabrizi and Anna Magnani. On the making of the film, Rossellini stated that the “situation of the moment guided by my own and the actors’ moods and perspectives” dictated what they shot, and he relied more on improvisation than on a script. He also stated that the film was “a film about fear, the fear felt by all of us but by me in particular. I too had to go into hiding. I too was on the run. I had friends who were captured and killed.”[4] Rossellini relied on traditional devices of melodrama, such as identification of the film’s central characters and a clear distinction between good and evil characters. Four interior sets were constructed for the more important locations of the film.

It was believed that the actual film stock was put together out of many different disparate bits, giving the film its documentary or newsreel style. But, when the Cineteca Nazionale restored the print in 1995, “the original negative consisted of just three different types of film: Ferrania C6 for all the outdoor scenes and the more sensitive Agfa Super Pan and Agfa Ultra Rapid for the interiors.” The previously unexplained changes in image brightness and consistency are now blamed on poor processing (variable development times, insufficient agitation in the developing bath and insufficient fixing).

It was one of the early Italian films of the war to depict the struggle against the Germans, unlike the films made in the early years of the war (when Italy was Germany’s ally under Mussolini) that depicted the British, Americans, Greeks, Russians and other allied countries, as well as Ethiopians, communists, and partisans as the antagonists. After the Allied Invasion of Italy in 1943, Italian morale crumbled, and they agreed to a separate peace with the allies, causing their former German allies to occupy large parts of Italy, intern Italian soldiers, deport Italian Jews to concentration camps, and treat many of its citizens with disdain for what they saw as a cowardly betrayal by one of their major allies.

Rome, Open City (1945)

Directed by: Roberto Rossellini

Starring: Anna Magnani, Aldo Fabrizi, Marcello Pagliero, Vito Annichiarico, Nando Bruno, Giovanna Galletti, Maria Michi, Carla Rovere, Eduardo Passarelli, Carlo Sindici, Joop van Hulzen

Screenplay by: Sergio Amidei, Federico Fellini

Production Design by: Rosario Megna

Cinematography by: Ubaldo Arata

Film Editing by: Eraldo Da Roma

Music by: Renzo Rossellini

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: Minerva Film (Italy)

Release Date: September 27, 1945

Views: 332