Eyes Without a Face movie storyline. At night just outside Paris, a woman drives along a riverbank and dumps a corpse in the river. After the body is recovered, Dr. Génessier identifies the remains as those of his missing daughter, Christiane Génessier, whose face was horribly disfigured in an automobile accident that occurred before her disappearance, for which he was responsible. Dr. Génessier lives in a large mansion, which is adjacent to his clinic, with numerous caged German Shepherds and other large dogs.

Following Christiane’s funeral, Dr. Génessier and his assistant Louise, the woman who had disposed of the dead body earlier, return home where the real Christiane is hidden (it’s explained that Louise is deathlessly loyal to Génessier because he repaired her own badly damaged face, leaving only a barely noticeable scar she covers with a pearl choker).

The body belonged to a young woman who died following Dr. Génessier’s unsuccessful attempt to graft her face onto his daughter’s. Dr. Génessier promises to restore Christiane’s face and insists that she wear a mask to cover her disfigurement. After her father leaves the room, Christiane calls her fiancé Jacques Vernon, who works with Dr. Génessier at his clinic, but hangs up without saying a word.

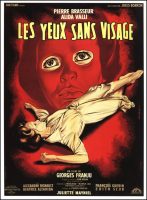

Eyes Without a Face (French: Les Yeux sans Visage) is a 1960 film co-written and directed by Georges Franju and starring Pierre Brasseur and Alida Valli, based on the novel of the same name by Jean Redon. Brasseur’s character is a plastic surgeon who is determined to perform a face transplant on his daughter, who was disfigured in an auto crash.

During the film’s production, consideration was given to the standards of European censors by setting the right tone, minimizing gore and eliminating the mad scientist character. Although the film passed through the European censors, the film’s release in Europe caused controversy nevertheless. Critical reaction ranged from praise to disgust.

The film received an American debut in an edited and dubbed form in 1962 under the title of The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus. In the United States, Faustus was released as a double feature with The Manster. The film’s initial critical reception was not overtly positive, but subsequent theatrical and home video re-releases improved its reputation. Modern critics praise the film for its poetic nature as well as being a notable influence on other filmmakers. It is considered a hallmark of art-horror.

About the Production

At the time, modern horror films had not been attempted by French film makers until producer Jules Borkon decided to tap into the horror market. Borkon bought the rights to the Redon novel and offered the directorial role to one of the founders of Cinémathèque Française, Franju, who was directing his first non-documentary feature La Tête contre les murs (1958).

Franju had grown up during the French silent-film era when filmmakers such as Georges Méliès and Louis Feuillade were making fantastique-themed films, and he relished the opportunity to contribute to the genre. Franju felt the story was not a horror film; rather, he described his vision of the film as one of “anguish… it’s a quieter mood than horror… more internal, more penetrating. It’s horror in homeopathic doses.”

To avoid problems with European censors, Borkon cautioned Franju not to include too much blood (which would upset French censors), refrain from showing animals getting tortured (which would upset English censors) and leave out mad-scientist characters (which would upset German censors). All three of these were part of the novel, presenting a challenge to find the right tone for presenting these story elements in the film.

First, working with Claude Sautet who was also serving as first assistant director and who laid out the preliminary screenplay, Franju hired the writing team of Boileau-Narcejac (Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac) who had written novels adapted as Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques (1955) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). The writers shifted the novel’s focus from Doctor Génessier’s character to that of his daughter, Christiane; this shift revealed the doctor’s character in a more positive and understandable light and helped to avoid the censorship restrictions.

For his production staff, Franju enlisted people with whom he had previously worked on earlier projects. Cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan, best remembered for developing the Schüfftan process, was chosen to render the visuals of the film. Schüfftan had worked with Franju on La Tête Contre les Murs (1958). Film historian David Kalat called Shüfftan “the ideal choice to illustrate Franju’s nightmares”.

French composer Maurice Jarre created the haunting score for the film. Jarre had also previously worked with Franju on his film La Tête Contre les Murs (1958). Modern critics note the film’s two imposing musical themes, a jaunty carnival-esque waltz (featured while Louise picks up young women for Doctor Génessier) and a lighter, sadder piece for Christiane.

Eyes Without a Face (1960)

Directed by: Georges Franju

Starring: Pierre Brasseur, Édith Scob, Alida Valli, Juliette Mayniel, Alexandre Rignault, Béatrice Altariba, Charles Blavette, Claude Brasseur, Yvette Etiévant, René Génin

Screenplay by: Georges Franju, Jean Redon, Pierre Boileau, Thomas Narcejac, Claude Sautet

Production Design by: Auguste Capelier

Cinematography by: Eugen Schüfftan

Film Editing by: Gilbert Natot

Costume Design by: Marie Martine, Hubert de Givenchy

Art Direction by: Margot Capelier

Music by: Maurice Jarre

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: Lux Compagnie Cinématographique de France

Release Date: March 2, 1960 (France)

Views: 205