Domicile Conjugal movie storyline. Some time after “Baisers Volés”, Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) and Christine Darbon (Claude Jade) are married and Antoine works dying flowers, and Christine is pregnant and gives private classes of violin. When Christine is near to have a baby, Antoine decides to find a new job, and he succeeds due to a misunderstanding of his employer. In a business meeting, he meets the Japanese Kyoko (Mademoiselle Hiroko) and they have an affair. When Christine accidentally discovers that Antoine has a lover, they separate. But later they miss each other and realize that they do love each other.

Bed and Board (French: Domicile Conjugal) is a 1970 French comedy-drama film directed by François Truffaut, and starring Jean-Pierre Léaud and Claude Jade. It is the fourth in Truffaut’s series of five films about Antoine Doinel, and directly follows Stolen Kisses, depicting the married life of Antoine (Léaud) and Christine (Jade). Love on the Run finished the story in 1979.

“The fourth installment in François Truffaut’s chronicle of the ardent, anachronistic Antoine Doinel, Bed and Board plunges his hapless creation once again into crisis. Expecting his first child and still struggling to find steady employment, Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) involves himself in a relationship with a beautiful Japanese woman that threatens to destroy his marriage. Lightly comic, with a touch of the burlesque, Bed and Board is a bittersweet look at the travails of young married life and the fine line between adolescence and adulthood.”

Film Review for Domicile Conjugal

So here he is for the last time, Antoine Doinel, who has grown up like the rest of us and has finally, apparently, found conjugal peace. He has changed a lot along the way. Francois Truffaut first introduced Antoine in “The 400 Blows” (1959), his first feature. The character was roughly based on Truffaut’s own youth and adolescence, when he was the next thing to a juvenile delinquent and prowled the streets of Paris.

“The 400 Blows,” with Godard’s “Breathless” (1960) and Chabrol’s “Le Beau Serge,” inaugurated the French New Wave and changed the face and style of filmmaking almost overnight. But we don’t remember “The 400 Blows” for historical reasons; we remember it because, for many of us, it was our first taste of personal, almost intimate, filmmaking.

The Hollywood movies we saw during the 1950s had grown increasingly sterile and clumsy, with a few exceptions, but now here was a new filmmaker with a relaxed and unstudied manner, who recorded the rhythms of life itself, Instead of some arthritic plot. He allowed us to spend some time with the boy Antoine, his parents, his school and his moody adolescent terrain. There are some movies that are spoken of in hushed tones as “classics,” and studied joylessly for their perfection, but “The 400 Blows” will never age like that. It will be one of the movies we can put in a time capsule to convince the next generations that some of us, at least, breathed.

With the exception of an interim short subject, Truffaut didn’t return to the autobiographical character of Antoine until “The Stolen Kisses” (1968), which once again starred Jean-Pierre Leaud. It was clear with this movie that Truffaut and Antoine had changed a great deal. “Stolen Kisses” was more on the side of whimsy than pathos, and wasn’t nearly as serious as the earlier film.

But it was a great film in its own way, showing us young Antoine in a variety of jobs and loves. At the end of “The 400 Blows,” we expected, I think, that Antoine would grow up to be an extraordinary human being of some sort, but we were wrong. Truffaut aged him into a pleasant, rather ordinary young man in his early 20s, and now with “Bed and Board,” Antoine has actually become bourgeois.

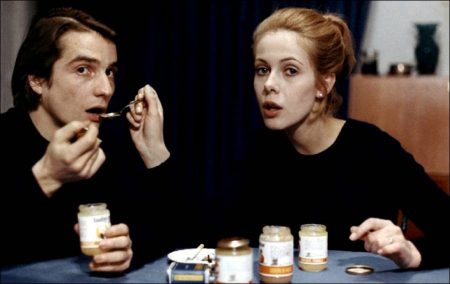

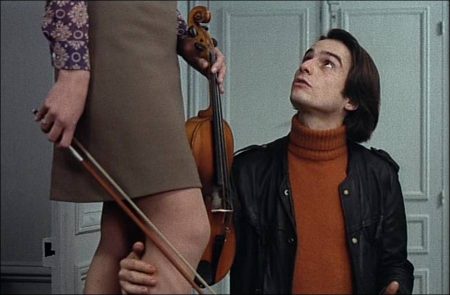

He’s married Christine, the girl who took him home for that disastrous dinner party in “Stolen Kisses,” and they’ve settled in a comfortable apartment, decorated with Christine’s touch, above the courtyard where Antoine works. (Seemingly unattracted to any vaguely ordinary job, Antoine dyes flowers.) The building is inhabited by the most motley assortment of boarders since the menagerie in “The Fifth Horseman Is Fear,” and Truffaut gives us an unstudied notion of the life around the courtyard.

Christine becomes pregnant after a decorous interval, and Antoine gets some sort of inexplicable job operating model boats for an American film. He also falls in love with a beautiful Japanese girl, and the affair picks up such momentum that Christine bars him from their bed. Alas, the other girl is addicted to saying “thank you” much too often, and Antoine finds that he’s developing leg cramps trying to eat close to the floor, Japanese style. He longs for Christine again, and she for him, and the movie has a happy ending.

Truffaut himself has changed enormously in the past decade, and Antoine’s story has become an autobiography, not of Truffaut’s life, but of his art. You get the feeling from his films that he’s one of the most gentle and civilized of directors, and that he finds the events of ordinary human life just as fascinating as heroic or melodramatic subjects. “Bed and Board” is one of the most decent and loving films I can remember. If it doesn’t provide quite the outcome we would have expected for Antoine, it will do.

Domicile Conjugal (1970)

Directed by: François Truffaut

Starring: Jean-Pierre Léaud, Claude Jade, Daniel Ceccaldi, Claire Duhamel, Daniel Boulanger, Silvana Blasi, Pierre Fabri, Barbara Laage, Billy Kearns, Claude Véga, Danièle Girard

Screenplay by: François Truffaut, Claude de Givray, Bernard Revon

Production Design by: Jean Mandaroux

Cinematography by: Nestor Almendros

Film Editing by: Agnés Guillemot

Costume Design by: Françoise Tournafond

Set Decoration by: Jean Mandaroux

Music by: Antoine Duhamel

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: Columbia Pictures

Release Date: September 9, 1970

Views: 262