Chocolat begins with an adult woman named France, walking down a road toward Douala, Cameroon. While walking, she is picked up by William J. Park (Emmet Judson Williamson), an African American who has moved to Africa and is driving to Limbe with his son. As they ride, France’s mind drifts and we see her as a young girl in Northern French Cameroon where her father was a colonial administrator.

The story is conducted through the eyes of young France, showing her friendship with the “houseboy”, Protée, as well the sexual tension between him and her young and beautiful mother, Aimée. The conflict of the film comes from the discomfort created as France and her mother attempt to move past the established boundaries between themselves and the native Africans.

This is brought to a head through Luc Segalen (Jean-Claude Adelin), a Western drifter who stays with the Dalens family after a small aircraft crashes nearby. He acknowledges Aimée’s attraction to Protée in the presence of other black servants. This later results in a fight between Luc and Protée, which Protée wins. During the fight, Aimée sits nearby, unseen by the two. She attempts to seduce Protée after Luc has left but he rejects her advance. Aimée consequently asks her husband to remove him from the house. Protée is moved from his in-house job to work outdoors in the garage as a mechanic.

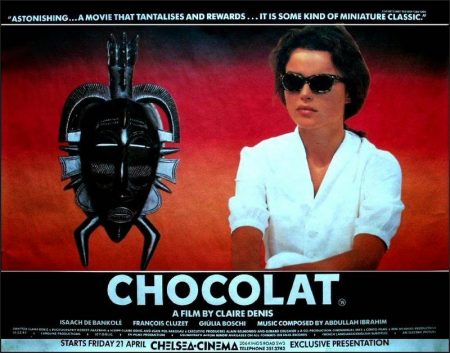

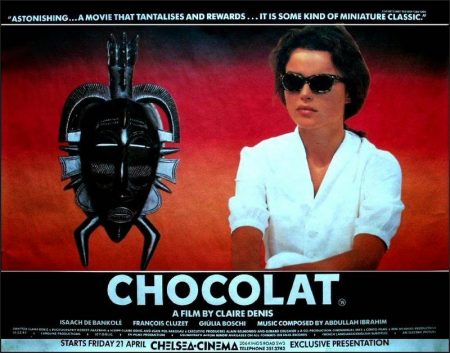

Chocolat is a 1988 film directed by Claire Denis, about a French family that lives in colonial Cameroon. Marc and Aimée Dalens (François Cluzet and Giulia Boschi) are the parents of France (Cécile Ducasse), a young girl who befriends Protée (Isaach de Bankolé), a Cameroon native who is the family’s household servant. The film was entered into the 1988 Cannes Film Festival.

Film Review for Chocolate

Claire Denis’ Chocolat (France / West Germany / Cameroon, 1988) begins with France Dalens (Mireille Perrier), a white French woman in her late twenties, returning to Cameroon to revisit her childhood home. On her way, she stops to enjoy an unpopulated beach and ends up obtaining a ride into the city from the only other people on the beach, William “Mungo” Park (Emmet Judson Williamson) and his son.

Mungo assumes that France is a French tourist who is “slumming” her way through Africa, but as France stares out the window, the film takes us back to when she was a little girl growing up in a colonial outpost in Cameroon, where her father was a captain in the French army. The rest of the film depicts a particular moment in her childhood that seems to best capture the interracial tensions and conflicts from that time.

The majority of the film relies on the visual rather than the verbal to explain the stresses that exist between France’s family, the servants and the family guests. Thus, it falls to the mise-en-scène and the camera placement to clue the audience into what the characters themselves dare not articulate. Not surprisingly, this visual commentary also clues us into larger metaphoric meanings regarding Cameroon, France, colonialism and the politics of desire.

Chocolat suggests that we structure desire not on the level of the verbal but instead in the field of the visible, which is where the characters’ unspoken longings are played out. In this sense, cinema becomes the privileged vehicle for the representation of colonial power because it can show how the field of the visible articulates power relations and relations of desire—and, of course, their intermingled nature.

To begin making this point, Denis and her director of photography Agnès Godard create a stunningly beautiful yet isolated portrait of Cameroon. The remote outpost where France’s family lives is vast and unpopulated. By placing the story in such an exquisite but lonely area, Denis can concentrate on the intimate relationships existing between a mere handful of characters. Just as these characters are trapped in their remote surroundings, they are also trapped in their roles as wife, servant, child, colonialist and so on. Denis works to highlight this by mapping out the house in terms of racial spaces, which are also demarcated as public or private ones.

The servants are all black Africans, and where they eat, shower, etc, are all public spaces, while the white family’s home (especially the bedroom and bathroom) are depicted as private spaces. The public spaces seem constantly on display. Several scenes in particular highlight this and in the process reveal the intensity of the relationship between France’s mother Aimée (Giulia Boschi), a French woman in her twenties, and Protée (Isaach De Bankolé), their Cameroon servant of about the same age. For while the flashback does depict the experience of France as a young girl (Cécile Ducasse), Aimée and Protée’s relationship is what drives the plot and what shapes France as a young girl and later as an adult.

The scenes between Aimée and Protée are often intensely personal, though staged in a completely public space. For example, in one particular scene, Protée is taking a shower. However, the shower for the male servants is outside—in plain view of the house. Denis sets this scene during the day when the colours are rich and the sun is high. We see a medium long shot of Protée soaping himself and then rinsing. Protée and the servants’ quarters are in the foreground of the frame, and the big house is in the background.

As he is showering, the audience is aware that Aimée and France are returning from a walk. As they reach the porch of the house, Protée also catches sight of them, which means that they can see him as well. Upon seeing them, he leans back and stifles a cry as he smashes his elbow against the wall behind him. While not one word is spoken throughout this entire scene, Denis reveals that the very layout of the colonial house with the servants on display is charged with desire. The servants’ quarters become a visual field that the colonialist surveys. But this field is also charged with sexual yearning.

Chocolat (1988)

Directed by: Claire Denis

Starring: Isaach De Bankolé, Giulia Boschi, François Cluzet, Jean-Claude Adelin, Laurent Arnal, Jean Bediebe, Jean-Quentin Châtelain, Emmanuelle Chaulet, Cécile Ducasse, Mireille Perrier

Screenplay by: Claire Denis, Jean-Pol Fargeau

Production Design by: Thierry Flamand

Cinematography by: Robert Alazraki

Film Editing by: Monica Coleman, Claudine Merlin, Sylvie Quester

Costume Design by: Christian Gasc

Makeup Department: Jean-Pierre Eychenne

Music by: Abdullah Ibrahim

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: Orion Classics

Release Date: May 18, 1988

Views: 290