Taglines: Luis Bunuel’s Masterpiece of Erotica!

Belle de Jour movie storyline. Séverine and Pierre are a young relatively newly married Parisienne couple in a comfortable upper middle class life. They are outwardly in a loving, happy marriage, which belies the fact that she more often than not rejects his romantic and sexual advances in the bedroom. He tolerates her rejections in his love for her. Although she tells him of the benign situations of her many dreams, she doesn’t tell him of the details, which always include he controlling and humiliating her in some form of sexual dominance.

She does not know why she rejects him sexually, or why she has such dreams. She learns from various sources that one of her distant married friends, a woman by the name of Henrietta, works as a prostitute in a high end brothel, which she didn’t know even existed. Although initially uncomfortable with both the thought and the actual actions of having sex with strange men for money, Séverine is nonetheless drawn to work in such an establishment. In doing so, Séverine may be able to exorcise some demons in her life, but perhaps not at others’ expense in the process.

Belle de Jour is a 1967 drama film directed by Luis Buñuel, and starring Catherine Deneuve, Jean Sorel, and Michel Piccoli. Based on the 1928 novel Belle de jour by Joseph Kessel, the film is about a young woman who spends her midweek afternoons as a high-class prostitute, while her husband is at work.

The title of the film is a pun on the French term, “belle de nuit” (“lady of the night”, i.e., a prostitute), but Séverine works during the day under the pseudonym “Belle de Jour”. Her nickname can also be interpreted as a reference to the French name of the daylily (Hemerocallis), meaning “beauty of [the] day”, a flower that blooms only during the day.

Belle de Jour is one of Buñuel’s most successful and famous films. It won the Golden Lion and the Pasinetti Award for Best Film at the Venice Film Festival in 1967. It stars Catherine Deneuve, Jean Sorel, Michel Piccoli, Pierre Clémenti, Françoise Fabian, Macha Méril, Muni, Maria Latour, Claude Cerval, Michel Charrel, Bernard Musson, Marcel Charvey, François Maistre and Francisco Rabal.

Film Review for Belle de Jour

In the days after I first saw Stanley Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut,” another film entered my mind again and again. It was Luis Bunuel’s “Belle de Jour” (1967), the story of a respectable young wife who secretly works in a brothel one or two afternoons a week. Actors sometimes create “back stories” for their characters — things they know about them that we don’t. I became convinced that if Nicole Kidman’s character in the Kubrick film had a favorite film of her own, it was “Belle de Jour.”

It is possibly the best-known erotic film of modern times, perhaps the best. That’s because it understands eroticism from the inside-out–understands how it exists not in sweat and skin, but in the imagination. “Belle de Jour” is seen entirely through the eyes of Severine, the proper 23-year-old surgeon’s wife, played by Catherine Deneuve. Bunuel, who was 67 when the film was released, had spent a lifetime making sly films about the secret terrain of human nature, and he knew one thing most directors never discover: For a woman like Severine, walking into a room to have sex, the erotic charge comes not from who is waiting in the room, but from the fact that she is walking into it. Sex is about herself. Love of course is another matter.

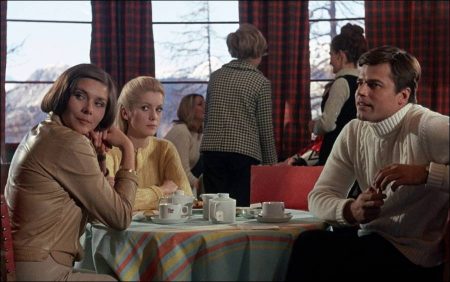

The subject of Severine’s passion is always Severine. She has an uneventful marriage to a conventionally handsome young surgeon named Pierre (Jean Sorel), who admires her virtue. She is hit upon by an older family friend, the saturnine Henri (Michel Piccoli, who was born looking insinuating). He’s also turned on by her virtue–by her blond perfection, her careful grooming, her reserve, her icy disdain for him. “Keep your compliments to yourself,” she says, when she and Pierre have lunch with him at a resort.

Her secret is that she has a wild fantasy life, and Bunuel cuts between her enigmatic smile and what she is thinking. Bunuel celebrated his own fetishes, always reserving a leading role in his films for feet and shoes, and he understood that fetishes have no meaning except that they are fetishes.

Severine is a masochist who likes to be handled roughly, but she also has various little turn-ons that the movie wisely never explains, because they are hers alone. The mewling of cats, for example, and the sound of a certain kind of carriage bell. These sounds accompany the film’s famous fantasy scenes, including the opening in which she rides with Pierre out to the country, where he orders two carriage drivers to assault her. In another scene, she is tied helplessly, dressed in an immaculate white gown, as men throw mud at her.

The turning point in Severine’s sexual life comes when she learns of exclusive Paris brothels where housewives sometimes work in the afternoons, making extra money while their husbands are at the office. Henri, who has her number, gives her the address of one. A few days later, dressed all in black as if going to her own funeral, she knocks at the door and is admitted to the domain of Madame Anais (Genevieve Page), an experienced businesswoman who is happy to offer her a job. Severine runs away, but returns, intrigued. At first she wants to pick and choose her clients, but Anais gives her a push, and when she answers “Yes, Madame,” the older woman smiles to herself and says, “I see you need a firm hand.” She understands Severine’s need and is pleased that it will bring her business.

There is no explicit sex in the movie. The most famous single scene — one those who have seen it refer to again and again — involves something we do not see and do not even understand. A client has a small lacquered box. He opens it and shows its contents to one of the other girls, and then to Severine. We never learn what is in the box. A soft buzzing noise comes from it. The first girl refuses to do whatever the client has in mind. So does Severine, but the movie cuts in an enigmatic way, and a later scene leaves the possibility that something happened.

What’s in the box? The literal truth doesn’t matter. The symbolic truth, which is all Bunuel cares about, is that it contains something of great erotic importance to the client. Into Madame Anais’ come two gangsters. One of them, young and swaggering, with a sword-stick, a black leather cape and a mouthful of hideous steel teeth, is Marcel (Pierre Clementi). “For you there is no charge,” Severine says quickly. She is turned on by his insults, his manner, and no doubt by her mental image of her cool perfection being defiled by his crude street manners. They have an affair, which leads up to the deep irony of the final melodramatic scenes–but what Marcel never understands is that while Severine is addicted to what he represents, she hardly cares about him at all. He is a prop for her fantasy life, the best one she has ever found.

Bunuel (1900-1983), one of the greatest of all directors, was almost contemptuous of stylistic polish. A surrealist as a young man, a collaborator with Salvador Dali on the famous “Un Chien Andalou” (1928), he was deeply cynical about human nature, but with amusement, not scorn. He was fascinated by the way in which deep emotional programming may be more important than free will in leading us to our decisions. Many of his films involve situations in which the characters seem free to act, but are not. He believed that many people are hard-wired at an early age into lifelong sexual patterns.

Severine is such a person. “I can’t help myself,” she says at one point. “I am lost.” She has a kind of resignation late in the film. She knows she has betrayed Pierre. For that matter, she knows she has used Marcel shamefully, even though that’s what he thought he was doing to her. In the words of Woody Allen, which contain as much despair as defiance, the heart wants what the heart wants.

The film is elegantly mounted — costumes, settings, decor, hair, clothes–and languorous in its pacing. Severine’s fate seems predestined. So does that of her husband, who as a weak man is swept away by the implacable strength of his wife’s desire. The best stylistic touches are the little ones, which someone unfamiliar with Bunuel might miss (although they work even if you don’t notice them). The subtle use of meows on the soundtrack; what do they represent? Only Severine knows. The weary wisdom about human nature: After Severine refuses an early client, Anais sends in another girl, then takes Severine into the next room to watch through a peephole and learn. “That is disgusting,” Severine says, turning away. Then she turns back and looks through the peephole again.

“Belle de Jour” and “Eyes Wide Shut” are both about similar characters — about staid, middle-class professionals whose marriages do not satisfy the fantasy needs of the wives. That long story about the Naval officer that Nicole Kidman’s character tells her husband is closely related to the scenarios that play out in Severine’s imagination. Both husbands remain clueless because what their wives desire is not about them, but about needs and compulsions so deeply engraved that they function at the instinctive level. Like a cat’s meow.

Belle de Jour (1967)

Directed by: Luis Buñuel

Starring: Catherine Deneuve, Jean Sorel, Michel Piccoli, Pierre Clémenti, Françoise Fabian, Macha Méril, Muni, Maria Latour, Claude Cerval, Michel Charrel, Bernard Musson, Marcel Charvey, François Maistre, Francisco Rabal

Screenplay by: Luis Buñuel, Jean-Claude Carrière

Production Design by: Robert Clavel

Cinematography by: Sacha Vierny

Film Editing by: Louisette Hautecoeur

Costume Design by: Hélène Nourry

Set Decoration by: Robert Clavel

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: Valoria (France), Euro International Films (Italy)

Release Date: May 24, 1967 (France), September 14, 1967 (Italy)

Views: 425