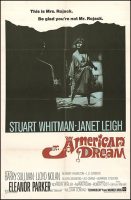

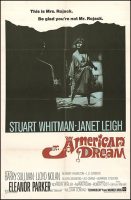

Taglines: This is Mrs. Rojack. Be glad you’re not Mr. Rojack.

An American Dream movie storyline. Former war hero Stephen Rojack is now a successful but controversial television commentator whose specialty is criticizing the police for not curtailing the activities of Cosa Nostra gang leader Ganucci. One evening Rojack receives a phone call from his estranged wife, Deborah, a wealthy and dissipated alcoholic. He visits her in the hope of getting her to agree to a divorce, but she unmercifully goads him into a violent fight which ends when Rojack strangles her and throws her from her 30-story penthouse.

When taken to police headquarters, where he insists that his wife’s death was a suicide, Rojack runs into Ganucci, the gangster’s nephew Nicky, and Nicky’s girl friend Cherry McMahon, a nightclub singer who once had an affair with Rojack. After being reluctantly released by the police, Rojack resumes his affair with Cherry, thereby further enraging the Cosa Nostra who decide to eliminate him. Rojack is then visited by Barney Kelly, his dead wife’s father, who harasses him into admitting that he killed Deborah.

Instead of turning the information over to the police, however, Mr. Kelly leaves Rojack to wrestle with his tormented conscience. Events come to a violent climax when Nicky persuades Cherry to help him trap Rojack in return for a new singing contract. She lures Rojack to her apartment but then tearfully warns him of the danger. No longer able to continue running, Rojack borrows Cherry’s revolver, enters the trap, and is gunned down after killing Nicky.

An American Dream (also known as See You in Hell, Darling) is a 1966 Technicolor drama film directed by Robert Gist and starring Stuart Whitman and Janet Leigh. It was adapted from the 1965 Norman Mailer novel of the same name. The film received an Oscar nomination for Best Song for “A Time for Love,” music by Johnny Mandel and lyrics by Paul Francis Webster.

About the Production

The film version of An American Dream (1966), which was based on Norman Mailer’s fourth novel, would have been an ambitious project for anyone as the storyline was heavily metaphorical and driven by the author’s wildly agitated but poetic prose style. Only an exceptionally gifted filmmaker would be able to pull it off and when Warner Bros. announced it had bought the rights to the novel, critic Pauline Kael wrote, “my reaction was that John Huston was the only man who could do it. And what a script it would be for him!….Possibly, because of the way that big movie stars and directors live in a world of their own, insulated and out of touch, he might not even recognize that An American Dream was the spectacle of our time; was, even, his spectacle.”

Unfortunately, Huston was not selected to direct An American Dream. Instead, the film version was a collaboration between three television industry veterans; actor/director Robert Gist (Naked City, Route 66), screenwriter Mann Rubin (Perry Mason, Mission: Impossible), and William Conrad, who started as a character actor in Hollywood (The Killers [1946]), moved into television directing in the late fifties and between 1965 and 1968 produced 10 low-budget films including Two on a Guillotine [1965], Brainstorm [1965] and The Cool Ones [1967]. An American Dream was easily the most ambitious project of them all and it proved to be a creative and commercial disaster.

There are so many things that went wrong in the translation from book to screen but one of the major flaws of the film version of An American Dream is the ambiguous presentation of Rojack. As played by Stuart Whitman, the protagonist is a conflicted, disillusioned man but still sympathetic and following his own moral code. In the novel, Rojack was a violent, raging alcoholic with delusions (he was convinced he was receiving messages from the Moon). He brutally murders his wife (in the film, the death is staged as an accident) and goes on a 24-hour bender, prowling a nocturnal world populated by prostitutes, gangsters, cops and drunks.

Writer / poet Ted Burke noted in an essay that Mailer’s novel came “at a time when the Hemingway cult of quiet, manly stoicism managed through a singular, privately held code of honor was exhausted of compelling narrative potential. Mailer’s idea was to see what would happen if the man who might have been the Hemingway hero, suffering his hurts in some poetic privacy, had instead a psychotic break.” The filmmakers obviously refrained from making their protagonist a self-destructive psychotic for fear of completely alienating audiences. But, as a result, Mailer’s viewpoint was lost for even though Rojack is obviously deranged and dangerous he can still see through the banalities and false promises of fame, wealth and the American dream.

Other aspects of Mailer’s novel become overstated and absurd when dramatized for the screen, particularly the depiction of Deborah’s death. Not only does she plunge to her death from the top of a penthouse balcony but as soon as her body hits the street, it is run over and dragged some distance by a car. Inside the car are gangster boss Ganucci, his chauffeur, and his mistress Cherry, and the trio end up at the police station for questioning where they encounter the murder suspect, Rojack. This sort of outrageous coincidence usually works better in fiction where a gifted writer can suspend the reader’s disbelief by spinning it as allegory or hallucination or a moment of madness. But in the movie version of An American Dream, the depiction of Deborah’s demise is so literal-minded that it achieves a flamboyant awfulness of immense proportions.

On some levels, An American Dream is almost as entertainingly bad as The Oscar, which was made the same year and shares some of the same acidic views of fame and fortune. Like that film, it also has its share of quotable lines that sound like they were culled from a Jacqueline Susann novel like Valley of the Dolls instead of Norman Mailer. “Never marry a rich woman buddy. There’s no way to prove to the rich that you aren’t after their money. They punish you for not loving them for themselves” or “I take pills, therefore I know I’m still alive.”

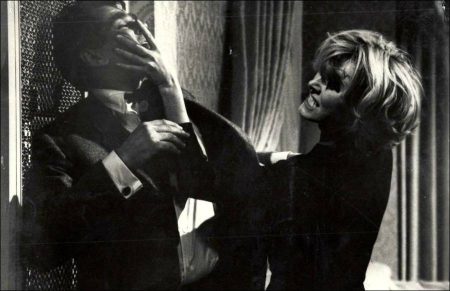

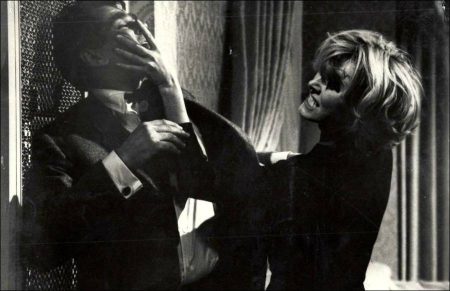

The most colorful exchanges are between Rojack and his shrieking banshee of a wife who lives to torment him with details of her affairs and puncture his self-confidence. In one exchange, she takes off her wedding ring and shoves it into his nose, sneering “Still fits, doesn’t it? I get what I paid for pet. Ten years ago I paid for you…my own little private war hero, just to see how long it would last in my kind of jungle with my kind of rules.”

Deborah is clearly an embodiment of the castrating female and in case we miss that metaphor, Eleanor Parker acts it out in one scene, using her fingers as mock scissors in a pantomime of clipping off Kojack’s tie and then works her way down his crotch…snip, snip, snip. Parker achieves operatic heights of hysteria and malice here (she was equally theatrical in The Oscar) and when she makes her spectacular exit from the film, her ferocious but pathetic character is solely missed.

The rest of the cast is dull by comparison but all of them, with the exception of Barry Sullivan who projects a gruff dignity as the justice-seeking police lieutenant, have rarely been more miscast or ill-used than here. Janet Leigh as Rojack’s former Las Vegas flame turned hooker/gangster moll is saddled with some of the most enigmatic and difficult dialogue of all.

When she invites Rojack up to her rooftop hideaway with a 360 degree view of Los Angeles’s bustling freeways, she says, “I don’t know whether it’s heaven or hell. It’s somewhere in between. That’s why I live here.” Like most of the dialogue in the film, the irony is driven home with a sledgehammer. One thing you can say about An American Dream, however, is that it is a true film noir and Leigh gets to deliver a great closing line that remains true to Mailer’s original bleak vision.

When Mailer’s novel first appeared it was attacked by many feminist writers, especially Kate Millett, for its portrayal and depiction of women. Yet, Mailer was no kinder to his male characters and An American Dream remains completely misanthropic in its view of the world. When the film version opened, most critics panned it. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote in his September 1st, 1966 review, “With four months still to go, the year’s worst movie may well turn out to be An American Dream…

Stuart Whitman, Janet Leigh, Eleanor Parker and Barry Sullivan are the hapless and we do mean hapless prisoners of this technicolored claptrap, which mixes standard gangster fare with soul-searching liverwurst… nothing turns out right for this picture, from the understandable but earnest confusion of Mr. Whitman, to the weird, walleyed utterances of Miss Leigh. Miss Parker, before her fatal nose-dive, behaves like a scalded cat.” And Pauline Kael dismissed it with her comments, “It has been written and directed by some fellows from television. The first fifteen minutes of Eleanor Parker in and out of bed can be recommended to connoisseurs of the tawdry, thought the movie as a whole doesn’t rank with The Oscar. The Oscar is the modern classic of the genre.”

An American Dream (1966)

Directed by: Robert Gist

Starring: Stuart Whitman, Janet Leigh, Eleanor Parker, Barry Sullivan, Lloyd Nolan, Murray Hamilton, Susan Denberg, Warren Stevens, Joe De Santis, Stacy Harris, Paul Mantee, George Takei, Kelly Jean Peters, James Nolan

Screenplay by: Mann Rubin

Production Design by:

Cinematography by: Sam Leavitt

Film Editing by: George R. Rohrs

Costume Design by: Howard Shoup

Set Decoration by: Ralph S. Hurst

Art Direction by: LeRoy Deane

Music by: Johnny Mandel

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: Warner Bros. Pictures

Release Date: August 31, 1966 (New York City)

Views: 346