A Gentle Woman opens with a falling scarf, leading us to a young woman’s dead body on the street. From the later scenes, we understand that the young woman was Elle (Dominique Sanda), who steps off the balcony of her Parisian apartment, plunging to her death. Why has she done it? As her distraught husband, Luc (Guy Frangin), looks over her dead body, and explores what led her to kill herself in a talk to the maid, the picture traces their lives together in flashbacks.

Elle is A Gentle Creature—meek, dreamy and thoughtful. She entrances Luc, who pursues her passionately. They marry, but the match never seems right. The story reveals their desperate, despairing miscommunication. Though they try many diversions (theater, television, films) these are momentary respites for the two of them (for Elle more-so, as we see with her interest in Hamlet, which plays out in an extended scene). Their dialogue only deepens her isolation and sadness.

A Gentle Woman (French: Une Femme Douce) is a 1969 French tragedy film directed by Robert Bresson. It is Bresson’s first film in color, and adapted from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1876 short story “A Gentle Creature” (Russian: Кроткая, romanized: Krotkaya). The film is set in contemporary Paris.

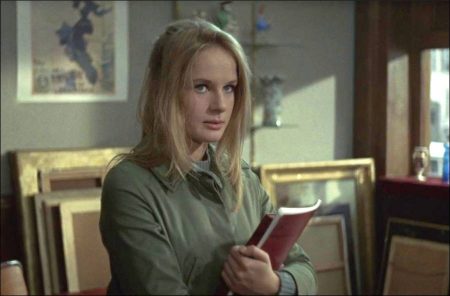

The tragedy is characterised by Bresson’s well known ascetic style, without any dynamic sequences or professional actors’ experienced and excessive expressions. Dominique Sanda, who plays the titular “gentle woman”, made her debut in the film, starting her career as an actress. Bresson chose her just as a result of her first voice call.

Although the film applies a background of 1960s Paris, such as Muséum national d’histoire naturelle and Musée National d’Art Moderne, its theme adheres closely to the novella. Bresson subsequently made another adaptation of Dostoevsky, his next film Quatre nuits d’un rêveur (Four Nights of a Dreamer) (1971) based on White Nights.

Film Review for A Gentle Woman

Touring as part of the Cinema Rediscovered festival, Robert Bresson’s 1969 classic finds its way back on to UK screens. Structured in flashback, Une Femme Douce explores how young woman Elle (Dominique Sanda) comes to kill herself outside her husband Luc’s (Guy Frangin) Parisian apartment.

A white scarf flutters through the warm Paris air as the owner lies prone on the concrete below, her face obscured. Off-screen, she is moved to her bed, as her husband and the maid who saw her fall. We know nothing of the woman – even her face is hidden from us. Perhaps it is to spare us – and her husband – from her injuries, yet in hiding her head, the frame weirdly dismembers Elle’s body.

This dismembering continues in flashback, as Luc recalls their first meetings in his antique shop. As she follows him up the stairs to weigh the gold crucifix she has brought to sell him, the camera focuses on their feet as it follows them up. Like a preemptive autopsy, the camera divides and examines her body meticulously, just as he does with the crucifix. Her on-screen dismemberment is an expression of Luc’s desire to control and possess her.

Fleeing her controlling parents, Elle desires freedom above all else, yet Luc treats her as one of his antiques, like an object commodified for his pleasure; her rejection of a bunch of wildflowers that he gives her is telling, both as a transactional object and as emblematic of freedom curtailed and commodified. After they marry, Elle frequently disappears, driving Luc mad with jealousy at the thought that she is with another man.

Meanwhile, Elle’s fascination with natural history, particularly that all animals are made from the same ‘raw materials’, suggests the essential, inescapable root of their depression. Made from the stuff, Elle and Luc remain irretrievably incompatible. Certainly, their fugue feels all-encompassing, the washed-out whites of Luc’s apartment complementing the greys of overcast skies and dimly-lit evenings.

Even Luc’s television set frequently turned on but rarely watched, seems perpetually out of focus, all static and blueish monochrome. The film’s muted qualities, its drained colours, languorous pace and understated, naturalistic sound design all tug the edges of unease; while the non-linear narrative suggests that time is out of joint.

An extended sequence in which the couple watch the final scene of Hamlet clues us into Luc’s psychology. Fancying himself somewhat as Shakespeare’s tragic character, he seems to forget that the emotional paroxysms and black moods of the eponymous Prince of Denmark drove his betrothed to suicide. As Luc looks on at the body of his wife, he seems oblivious to the fact that his singular narration – his centring himself as the sole subject in their relationship – may have been what unbalanced them in the first place.

A Gentle Woman (1969)

Directed by: Robert Bresson

Starring: Dominique Sanda, Guy Frangin, Jeanne Lobre, Claude Ollier, Jacques Kébadian, Gilles Sandier, Dorothée Blanck

Screenplay by: Robert Bresson

Production Design by: Pierre Charbonnier

Cinematography by: Ghislain Cloquet

Film Editing by: Raymond Lamy

Music by: Jean Wiener

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: Les Films Paramount (France), New Yorker Films (United States)

Release Date: August 28, 1969 (France), May 27, 1971 (United States)

Views: 306